Argentine Air Force

The Argentine Air Force (Spanish: Fuerza Aérea Argentina, or simply FAA) is the national aviation branch of the Armed Forces of the Argentine Republic. In 2010, it had 14,600 military personnel and 6,900 civilian personnel.[2]

| Argentine Air Force | |

|---|---|

| Fuerza Aérea Argentina | |

.svg.png.webp) Badge of the Argentine Air Force | |

| Founded | 4 January 1945 |

| Country | |

| Type | Air force |

| Role | Aerial warfare |

| Size | 13,837 personnel and 217 aircraft [1] |

| Part of | Argentine Armed Forces |

| Nickname(s) | FAA |

| March | Spanish: Alas Argentinas "Argentine Wings" |

| Anniversaries | 10 August (anniversary) 1 May (Baptism of fire during the Falklands War) |

| Equipment | 139 aircraft |

| Engagements | |

| Website | www |

| Commanders | |

| Commander-in-Chief | President Alberto Fernández |

| Chief of Staff of the Air Force | Brigadier Xavier Isaac |

| Insignia | |

| Roundel |   |

| Fin flash |  |

| Aircraft flown | |

| Attack | A-4AR, Pampa |

| Fighter | A-4AR |

| Helicopter | Bell 412, Bell 212, Hughes 500D, SA315, Mil Mi-171 |

| Patrol | Tucano |

| Reconnaissance | Pucará |

| Trainer | T-6 Texan II, T-34, Tucano, Pampa, Grob 120TP |

| Transport | C-130, DHC-6 |

History

The Air Force's history began with the establishment of the Army Aviation Service's Escuela de Aviación Militar ('Military Aviation School') on 10 August 1912 by President Roque Sáenz Peña.

Several pioneers of Argentine aviation include the conscript Pablo Teodoro Fels and the retired Argentine Navy officer Jorge Newbery.[3] The school began to turn out military pilots who participated in milestone events in Argentine aviation, such as the crossing of the Andes.

Interwar period

In the years following World War I, the Argentine Air Force received various aircraft from France and Italy.[4] In 1922, the Escuela Militar de Aviación was temporarily disbanded, resulting in the formation of Grupo 1 de Aviación ('Aviation Group One') as an operational unit. Three years later, in 1925, the Escuela Militar de Aviación was reopened, and the Grupo 3 de Observación ('Observation Group Three') unit was created. Shortly after, Grupo 1 de Aviación became known as Grupo 1 de Observación.

In 1927, the Dirección General de Aeronáutica ('General Aeronautics Authority') was created to coordinate the country's military aviation. In that same year, the Fábrica Militar de Aviones (lit. 'Military Aircraft Factory', FMA), which would play a crucial role in the country's aviation industry, was founded in Córdoba.[3] Despite that, throughout the 1930s, Argentina acquired various aircraft from the United Kingdom, Germany, and the United States.

By 1938–39, Argentina's air power comprised roughly 3,200 personnel (including about 200 officers) and maintained about 230 aircraft. About 150 of these were operated by the army and included Dewoitine D.21 and Curtiss P-36 Hawk fighters; Breguet 19 reconnaissance planes; Northrop A-17 and Martin B-10 bombers, North American NA-16 trainers, Focke-Wulf Fw 58 as multi-role planes, Junkers Ju 52, and Fairchild 82 transports. About 80 were operated by the navy and included the Supermarine Southampton, Supermarine Walrus, Fairey Seal, Fairey III, Vought O2U Corsair, Consolidated P2Y, Curtiss T-32 Condor II, Douglas Dolphin, and Grumman J2F Duck.[5]

World War II and immediate post-war

The first step towards the establishment of the Air Force as a separate branch of the Armed Forces was taken on February 11, 1944 with the establishment of the Aeronautical Command-in-Chief (Comando en Jefe de Aeronáutica) directly under the mandate of the Department of War. This later became the Argentine Air Force by decree on January 4, 1945, which also created the Secretary of Aeronautics (Secretaría de Aeronáutica).[3][6]

At the end of World War II, the Air Force began a process of modernization. This 'golden age' (roughly 1945–1955) was ushered in by the availability of foreign currency in Argentina; the abundance of now unemployed airspace engineers from Germany, Italy, and France; and the British provision of latest-generation engines and other aircraft parts. In his first term, President Juan Perón brought teams of European engineers to the FMA, nowadays the Instituto Aerotécnico ('Aerotechnical Institute'), or I.Ae., to push forward the aircraft technological development, totaling roughly 750 workers. This included two teams of German designers (led by Kurt Tank), and the French engineer Émile Dewoitine.[3]

In 1947, the Air Force acquired 100 Gloster Meteor jet fighters. These aircraft were paid for by the United States of America as a way to partially pay back its debt to Argentina, who provided them with raw materials during World War II. This acquisition made the Argentine the first air force in Latin America equipped with jet-propelled combat fighters. In addition, a number of Avro Lincoln and Avro Lancaster bombers were acquired.[3]

The Air Force, with former Luftwaffe officers as consultants and with the European teams that Perón had brought, also began to develop its own aircraft e.g. the I.Ae. 27 Pulqui I and I.Ae. 33 Pulqui II.[7] These manufactures made Argentina the first country in Latin America and the sixth in the world to develop jet fighter technology on its own. Other Argentina-developed, twin-engine aircraft include the I.Ae. 35 Huanquero, the I.Ae 22 DL advanced trainer, the I.Ae 24 Calquín bomber, the I.Ae. 23 trainer, the bi-motor combat fighter I.Ae. 30 Ñancú, the assault glider I.Ae. 25 Mañque, as well as rockets and planes for civilian use (like the FMA 20 El Boyero).

In the Revolución Libertadora (1955)

The Argentine Air Force opened fire for the first time on June 16, 1955 during the bombing of the Plaza de Mayo in Buenos Aires, in which government-loyal Gloster Meteors fought rebel planes attempting to assassinate the President in a coup d'état (this plan failed, and instead the rebels bombed the city and the House of Government).[8][9] In the following September coup, the Air Force supported Perón's government by fighting the coup; initiating combat operations and transporting troops and arms.[10] Only five aircraft defected to the other side.[11] After the Revolución Libertadora succeeded and the coup took place, previously mentioned operations ceased and most Air Force workers left the country, including engineer Kurt Tank who left to work in India.

Antarctic support

In 1952, the Air Force started flying to supply the Antarctic scientific bases using ski-equipped Douglas C-47s[12] and establishing Marambio Base on 25 September 1969. Previously, President Juan Perón had created the Antarctic Task Forces (FATA, Fuerzas de Tareas Antárticas) for this purpose.[13] On April 11, 1970,[14] they began operating C-130 Hercules aircraft into the Antarctica. The first flight to land in Marambio Base was on board the one registered TC-61, commanded by Commodore Arturo Athos Gandolfi. The Fokker F-28 Fellowship presidential aircraft T-01 Patagonia is reported to be the first jet to have landed there, on July 28, 1973.[15][16] Since the 1970s, DHC-6 Twin Otters have also been deployed.[17] In October 1973, the Air Force launched the Operation Transantar, achieving the first trans-Antarctic three-continent flight in history when a Hercules C-130 flew between Río Gallegos; Marambio Base; Christchurch, New Zealand and Canberra, Australia.[18][19]

Modernization (1960s–1970s)

In the 1960s, new aircraft were incorporated, including the F-86F Sabre jet fighter and the Douglas A-4 Skyhawk mainly used for ground-attack. U.S. Air Force Major Manuel J. Fernandez, a Spanish-speaking Sabre ace who shot down 14 enemy aircraft in the Korean War on board that aircraft, was dispatched to the Mendoza airbase from 1960–1962 to personally train Argentine pilots flying the model. During the 1970s, the Air Force re-equipped itself with modern aircraft, including Mirage III interceptors, IAI Dagger multi-role fighters (Ex-Israeli, comparable to the Mirage V), and C-130 Hercules cargo planes. A counter-insurgency airplane, the Pucará, was also manufactured and used in substantial numbers. The Air Force also had an important role in the 1976 coup which lead to a military dictatorship that lasted until 1983.[20]

Falklands War (Guerra de las Malvinas) (1982)

The Falklands War was the first war fought by the Argentine Air Force against an external enemy. They were unprepared for this war: in comparison to Britain's most modern weapons, some of the Argentine aircraft were obsolete.[21] During the war, the Air Force division of the Military Junta was called the Fuerza Aérea Sur (FAS, 'Southern Air Force'), led by Ernesto Crespo.[22]

Air action began on May 1, 1982.[23] The UK's Royal Air Force initiated Operation Black Buck, in which an Acro Vulcan XM607 bomber attacked the military air base on the islands. The Task Force then proceeded to send Sea Harriers to attack positions at Stanley (officially in Argentina Puerto Argentino) and Goose Green (in Spanish: Pradera del Ganso), where the first Argentine casualties occurred.[24]

The Argentine Air Force reacted by sending IAI Dagger and A-4 Skyhawk attack aircraft, and Mirage III interceptors. The Mirage III went into combat with the Harriers on Bourbon Island, with one Mirage lost to a Harrier. On May 21, the Battle of San Carlos ("Bomb Alley") began when the Air Force attacked a detachment of British ships making a landing in the San Carlos Water. The Dagger and Skyhawk aircraft sank three British ships (HMS Coventry, a Type 42 destroyer; two frigates, HMS Antelope and HMS Ardent) and damaged another eight ships.

During the march of June 8, the Air Force carried out an operation in Bluff Cove. The British needed to position Infantry Brigade 5 to complete their lock on Port Stanley. For this they used the landing ships RFA Sir Galahad and RFA Sir Tristram. Seven A-4 Skyhawks were used in the attack. Six Daggers attacked the frigate, HMS Plymouth. The Skyhawks destroyed Sir Galahad and the landing craft Foxtrot 4. They also severely damaged Sir Tristram. Three A-4s were lost through interception by the Harriers. All the bombs dropped by the Daggers failed to explode.

On June 13, the A-4 Skyhawks of the Argentinian Air Force renewed their attacks. They were in two formations of four planes each. They launched an attack against enemy troops and helicopters. On June 14, 1982, the Argentine command surrendered. The United Kingdom regained control of the Falklands, Georgia, and the South Sandwich Islands. The Argentine Air Force suffered 55 dead and 47 wounded, with 505 combat departures and 62 aircraft losses, as listed below:[25]

- 19 A-4 Skyhawk

- 2 Mirage III

- 11 Dagger

- 2 Canberra

- 24 IA-58 Pucará

- 1 C-130H Hercules

- 1 Learjet 35

- 2 Bell 212

Postwar (1983–2003)

After the war, the UK imposed an arms embargo on Argentina, which was discontinued in the 1990s. After attempts to acquire surplus IAI Kfirs or F-16s failed for economic and political reasons, the United States military sold Argentina 36 A-4AR Fightinghawks, a refurbished and upgraded version of the A-4 Skyhawks used in the war. Other equipment was bought: 23 US Army surplus OV-1 Mohawks, 22 Ex-Israeli IAI Dagger, 2 C-130B, and 1 Lockheed L-100-30.

After the war, to avoid becoming dependent to other countries for their aeronautic technology, Argentina started planning the development of new aircraft including the FMA IA-63 Pampa, the combat fighter FMA SAIA 90, and the transformation of the Condor missile into a medium-range ballistic missile.[26] Of these, only the Pampa was successfully developed. The SAIA 90 was canceled by President Raúl Alfonsin to focus on the Condor, while the Condor was canceled in the 1980s by President Carlos Menem.

In 1994, Menem discontinued mandatory military service (commonly known as La Colimba) in Argentina and established voluntary military service for 10 years. He also allowed the presence of women into military service.[27]

Support to UN peacekeeping missions

The Air Force has been involved in United Nations peacekeeping missions around the world. They sent a Boeing 707 to the 1991 Gulf War. Since 1994 the UN Air contingent (UNFLIGHT) in Cyprus under UNFICYP mandate is provided by the Air Force,[28] having achieved 10,000 flight hours by 2003 without any accidents.[29] It has also deployed, since 2005, Bell 212 helicopters to Haiti under MINUSTAH mandate, and has been involved with UN peacekeeping in Cyprus as the Argentine Task Force (Fuerza de Tarea Argentina).

Early 21st century

In early 2005, seventeen brigadiers, including the Chief of Staff, Brigadier General Carlos Rohde, were sacked by President Néstor Kirchner following a scandal involving drug trafficking through Ezeiza International Airport. Kirchner cited failures in the security systems of the Argentine airports, which were overseen by the National Aeronautic Police, then a branch of the Air Force (predecessor of the today independent Airport Security Police), and cover-ups of the scandal.[30] It later became known that many government agencies, among them the Ministry of the Interior, the Customs Administration and the Secretariat of State Intelligence knew about the drug trafficking.

In 2007, the Air Force began participation in Operation Fortín to monitor the Argentine airspace for drug trafficking. They also began using aerial measures to monitor wildfires as part of the National Plan for Fire Management.

The primary concerns of the Air Force as of 2010 are the establishment of a radar network for the use of the air traffic controllers, the replacement of its older combat aircraft (Mirage III, Mirage V) and the incorporation of new technologies.

Since the 1990s the Air Force has established good relations with its neighbors, the Brazilian and Chilean Air Forces. They annually meet, on a rotation basis, in the joint exercises Cruzex in Brazil, Ceibo in Argentina and Salitre in Chile.

In 2007 an FAA FMA IA 58 Pucará was converted to use a modified engine operating on soy-derived bio-jet fuel. The project, financed and directed by the Argentine Government (Secretaría de Ciencia Tecnología e Innovación Productiva de la Nación), made Argentina the second nation in the world to propel an aircraft with bio-jet fuel. The purpose of the project is to make the FAA less reliant on fossil fuels.

2010s

As of 2010 budgetary constraints continued, leading to the disbanding of the Boeing 707 transport squadron and maintenance problems for half of the C-130 Hercules fleet. This was particularly evident when, in a matter of days in March, the same C-130 aircraft could be seen, in addition to their routine missions, traveling 3 times to Haiti, 9 times to Chile (in both cases delivering humanitarian aid) and also doing a resupply airdrop to the Argentine southernmost Antarctic base Belgrano II.

In August 2010 a contract was signed for two Mi-17E helicopters, plus an option on a further three, to support Antarctic bases[31][32] although no official destination for them have been released yet and is possible that they will be assigned to the Argentine Army Aviation.

The FAA is seeking to replace its ageing force with a more capable and more serviceable modern aircraft. The acquisition of Spanish Mirage F1Ms, IAI Kfir Block 60s[33] and Saab Gripen E/Fs was considered, but as of February 2015, all of those deals appear to have stalled; The Mirage F1 deal was scrapped by the Spanish government in March 2014 after pressure of the UK to not assist in FAA modernization over tensions between the countries over the Falkland Islands.[34] The UK has also managed to veto the sale of Gripen E/Fs, as 30% of the Gripen's parts are manufactured there. The deal with Israel has reportedly stalled for technical and political reasons. China has reportedly offered JF-17/FC-1 or Chengdu J-10 to Argentina. The two countries have formed a working group to look into the transfer of 14 aircraft.[35][36] Russia had also offered to lease 12 Su-24 strike aircraft to the FAA, but Jane's reported that the Su-24 would not be very useful to the FAA and that "it would appear that any proposed transfer of such aircraft is likely the result of Russia playing political games with the UK over the continuing crisis in Ukraine.".[37] All Mirages were officially decommissioned on 30 November 2015.[38] The A-4s were grounded as of January 2016 for lack of spares;[39] in any case only 4–5 were airworthy with the rest in storage at Villa Reynolds.[40] When Barack Obama visited in March 2016, Air Force One was accompanied by US Air Force F-16s because Argentina could only offer Pucarás and Pampas for air defense.[41]

As of July 2019, the Argentine Air Force and government selected the KAI FA-50 as its interim fighter. It was to be the first step in modernizing the fighter force and replacing the Mirage 3, Dagger, and Mirage 5 fighters that have been retired. It was also anticipated to help in the retirement of the A-4AR Fightinghawk fleet, as they are now aging and becoming difficult to maintain. In 2020, it was reported that as few as six of the Fightinghawk aircraft remained operational.[42] While no specific numbers of aircraft to purchase were given, the media reported that up to 10 FA-50s were in the deal. Despite elections coming in October 2019, the deal had been expected to go through. An Argentine delegation first visited the Republic of Korea Air Force in September 2016. At that time an FAA pilot was able to test fly the TA-50 Golden Eagle operational trainer variant of the FA-50.[43]

However, the deal appeared to have been canceled in early 2020 leaving the Air Force without a fighter replacement. Some sources suggested that the cancellation was due to the financial pressures resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic,[44] while others reported that British intervention played a part by preventing the export of an aircraft incorporating various British components.[45] In October 2020, Korea Aerospace Industries (KAI) confirmed that since major components of the aircraft were supplied by the U.K., the aircraft could not be exported to Argentina. Britain similarly blocked the potential sale of Brazilian license-built Saab Gripen aircraft to Argentina given avionics that were of British origin. Argentina was now said to be exploring the potential acquisition of aircraft from Russia or China,[46] or alternatively JF-17 aircraft from Pakistan.[47]

Organization

The FAA is one of the three branches of the Argentine military, having equal status with the Army and the Navy. The President of Argentina is Commander-in-Chief of all three services.[48]

The FAA is headed by the Chief of the General Staff (Jefe del Estado Mayor General), directly appointed by the President.[48] The Chief of Staff usually holds the rank of Brigadier General, the highest rank of the Air Force. The Chief of Staff is seconded by a Deputy Chief of the General Staff and three senior officers in charge of the FAA's three Commands: the Air Operations Command, the Personnel Command and the Materiel Command.

The Air Operations Command (Comando de Operaciones Aéreas) is the branch of the Air Force responsible for aerospace defense, air operations, planning, training, technical and logistical support of the air units. Subordinate to the Air Operations Command are the Air Brigades (Brigadas Aéreas), the Air Force's major operative units, as well as the airspace surveillance and control group (Grupo VYCEA, Argentine Air Force). A total of eight air brigades are currently operational. Brigades are headquartered at Military Air Bases (Base Aérea Militar (BAMs).

Each Air Brigade is made up of three Groups, each bearing the same number as their mother Brigade. These groups include:

- One Air Group (Grupo Aéreo), which operates the aircraft assigned to the Brigade. The Air Group is divided into a variable number of Air Squadrons. Air Groups may be named according to their primary mission, for example, an air group specialized in fighter operations receives the designation of Fighter Group (Grupo de Caza). Currently, the Air Force includes three Fighter Groups (4th, 5th, and 6th), one Attack Group (3rd), one Transport Group (1st), and three plain Air Groups (2nd, 7th, and 9th). The 7th Air Group operates all the helicopters of the Air Force, while the 2nd includes a small reconnaissance unit as well as light transport aircraft. 9th Air Group is a light transport unit.

- One Technical Group (Grupo Técnico), in charge of the maintenance and repair of the Brigade's aircraft.

- One Base Group (Grupo Base), responsible for the airbase itself, weather forecasting, flight control, runway maintenance, etc. Base Groups also include Base Flights (Escuadrillas de Base), generally made up of two or three liaison aircraft.

The Personnel Command (Comando de Personal) is responsible for the training, education, assignment, and welfare of Air Force personnel. Under the control of the Personnel Command are the Military Aviation School (which educates the future officers of the Air Force), the Air Force Non-Commissioned Officer (NCO) School, and other educational and training units.

The Materiel Command (Comando de Material) deals with planning and executing the Air Force's logistics regarding flying and ground materiel. Materiel Command includes "Quilmes" and "Río Cuarto" Material Areas (repairing and maintenance units) and "El Palomar" Logistical Area.

Order of battle

- 1st Air Brigade (El Palomar Military Air Base, Buenos Aires Province) in El Palomar Airport[49]

- 1st Air Transport Squadron (C-130H Hercules; KC-130H Hercules; L-100-30 Hercules)

- 2nd Air Transport Squadron (Fokker F-28)

- 5th Squadron (Boeing 707 retired)

- 2nd Air Brigade (Paraná Military Air Base, Entre Ríos Province) in General Justo José de Urquiza Airport[49]

- 2nd Reconnaissance Squadron (Learjet 35A)

- 4th Squadron (Fokker F27-400M retired)

- Services Squadron (Cessna 182)

- 3rd Air Brigade (Reconquista Military Air Base, Santa Fe Province) in Daniel Jukic Airport[49]

- Services Squadron (Cessna 182)[50]

- 14th Antiaircraft Artillery Battery (Oerlikon GAI-D01; Elta EL/M-2106)

- 4th Air Brigade (El Plumerillo Military Air Base, Mendoza Province) in Governor Francisco Gabrielli International Airport[49]

- 1st Training Squadron (FMA IA-63 Pampa serie 2)

- 3rd Search and Rescue Squadron (SA-315B Lama)

- 4th Cruz del Sur Aerobatics Squadron (Su-29 retired)

- Fighter School

- 4th Antiaircraft Artillery Battery (Oerlikon GAI-D01; Elta EL/M-2106)

- West Tactical Intelligence Squadron

- 5th Air Brigade (Villa Reynolds Military Air Base, San Luis Province) in Villa Reynolds Airport[49]

- 1st Fighter-Bomber Squadron (A-4AR Fightinghawk)

- 2nd Fighter-Bomber Squadron (A-4AR Fightinghawk)

- Services Squadron (Cessna 182; Hughes 500D)

- 5th Antiaircraft Artillery Battery (Rheinmetall RH 202; Elta EL/M-2106)

- 6th Air Brigade (Tandil Military Air Base, Buenos Aires Province) in Tandil Airport

- 1st Fighter-Bomber Squadron (AMD Mirage 5P Mara retired)[49]

- 2nd Fighter-Bomber Squadron (IAI Finger retired)

- 3rd Air Interceptor Squadron (AMD Mirage IIIEA/DA retired)

- Unknown Squadron (IA-63 Pampa II)[50]

- Services Squadron (Cessna 182; Aerocommander 500)[50]

- 13th Antiaircraft Artillery Battery (Oerlikon GAI-B01)

- 7th Air Brigade (Moreno Military Air Base, Buenos Aires Province) in Mariano Moreno Airport[49]

- 1st Search and Rescue Squadron (Bell 212; Bell 412EP)

- 2nd Tactical Squadron (Hughes 500D)

- 3rd Squadron (Mil Mi-171E)

- Special Operations Group (Spanish: Grupo de Operaciones Especiales, GOE)

- 9th Air Brigade (Comodoro Rivadavia Military Air Base, Chubut Province) in General Enrique Mosconi International Airport[49]

- 6th Air Transport Squadron (SAAB 340B)

- 7th Air Transport Squadron (DHC-6 Twin Otter)

- 7th Antiaircraft Artillery Battery (Rheinmetall RH 202)

- South Tactical Intelligence Squadron

- Morón Military Air Base (Buenos Aires Province) in Morón Airport[49]

- Unknown Squadron (Piper PA-34-220T Seneca; Piper/Chincul PA-28RT-201 Arrow; Piper PA-28-236 Dakota; Cessna 182)

- Mar del Plata Military Air Base (Buenos Aires Province) in Astor Piazzolla International Airport[49]

- Unknown Squadron (Roland II; Rheinmetall RH 202; Oerlikon GAI-D01; Oerlikon GDF-002; Skyguard)

- Antiaircraft Weapons Maintenance Squadron (UAV Pegasus; UAV Tehuelche; UAV Murciélago)

- Río Gallegos Military Air Base (Santa Cruz Province) in Piloto Civil Norberto Fernández International Airport[49]

- Unknown Squadron (AN/TPS-43)

- 6th Antiaircraft Artillery Battery

- Military Aviation School (Cordoba, Córdoba Province)[51]

- Glider Flight

- Services Squadron

- School Air Squadron (Grob G 120TP; Embraer EMB-312 Tucano)

Ranks

Officers

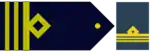

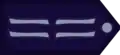

Officers wear their rank insignia in their sleeves, in the pattern depicted below. There are also shoulderboards with the same insignia (albeit in gray) for the ranks between Ensign and Commodore. General officers wear different shoulder boards.

| Insignia | Equivalent NATO Rank Code | Rank in Spanish | Rank in English | Commonwealth equivalent | US Air Force equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

OF-9 | Brigadier General | Brigadier General | Air Chief Marshal | General |

|

OF-8 | Brigadier Mayor | Brigadier-Major | Air Marshal | Lieutenant General |

|

OF-7 | Brigadier | Brigadier | Air Vice-Marshal | Major General |

|

OF-6 (honorary rank) | Comodoro Mayor | Commodore Major (honorary rank given to Commodores) |

Air Commodore | Brigadier General |

|

OF-5 | Comodoro | Commodore | Group Captain | Colonel |

|

OF-4 | Vicecomodoro | Vice-Commodore | Wing Commander | Lieutenant Colonel |

|

OF-3 | Mayor | Major | Squadron Leader | Major |

|

OF-2 | Capitán | Captain | Flight Lieutenant | Captain |

|

OF-1 | Primer Teniente | First Lieutenant | Flying Officer | First Lieutenant |

|

OF-1 | Teniente | Lieutenant | Pilot Officer | Second Lieutenant |

|

OF-D | Alférez | Ensign | Acting Pilot Officer |

Non-commissioned officers and enlisted personnel

| Insignia | Rank in Spanish | Rank in English | US Air Force equivalent | RAF equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Suboficial Mayor | Senior Sub-Officer | Chief Master Sergeant, Command Chief Master Sergeant |

Warrant Officer |

|

Suboficial Principal | Chief Sub-Officer | Senior Master Sergeant | Chief Technician |

| Suboficial Ayudante | Adjutant Sub-Officer | Master Sergeant | Flight Sergeant | |

| Suboficial Auxiliar | Auxiliary Sub-Officer | Technical Sergeant | Sergeant | |

| Cabo Principal | Principal Corporal | Staff Sergeant | Corporal | |

| Cabo Primero | Corporal First Class | Senior Airman | Junior Technician Senior Aircraftman Technician/Senior Aircraftwoman Technician Lance Corporal | |

| Cabo | Corporal | Airman First Class | Senior Aircraftman/Senior Aircraftwoman | |

| Voluntario Primero | Volunteer First Class | Airman | Leading Aircraftman/Leading Aircraftwoman | |

| Voluntario Segundo | Volunteer Second Class | Airman Basic | Aircraftman/Aircraftwoman |

Aircraft

Current inventory

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Chiefs of the Argentine Air Force

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Air force of Argentina. |

Argentine military – other air services

Operational use

Units and related organisations

- Agrupación Aérea Presidencial – Presidential VIP fleet

- Argentine Air Force Mobile Field Hospital

- LADE – State government airline

References

Citations

- "Argentina hace publica la cantidad de personal militar en sus fuerzas". zona-militar.com. 19 March 2018. Archived from the original on 28 April 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- IISS 2010, pp. 64–67

- "Fuerza AĆ©rea Argentina". 2018-09-03. Archived from the original on 2018-09-03. Retrieved 2020-05-20.

- "Argentina Air Force". www.aeroflight.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-09-06.

- Schnitzler, R.; Feuchter, G.W.; Schulz, R., eds. (1939). Handbuch der Luftwaffe [Aviation Manual] (in German) (3rd ed.). Munich and Berlin: J. F. Lehmanns Verlag. p. 13.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20080221233458/http://www.fuerzaaerea.mil.ar/historia/enero.html. Archived from the original on 2008-02-21. Retrieved 2020-05-20. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Peck, Michael. "In the 1950s, Argentina Tried To Build a Nazi Fighter Jets". The National Interest. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- "La Plaza de Mayo tuvo 308 muertos - Criticadigital.com". 2010-06-18. Archived from the original on 2010-06-18. Retrieved 2020-05-20.

- "Los bombardeos del '55: Cuando el odio quedó impune". Facultad de Periodismo y Comunicación Social de la Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Retrieved 2020-05-20.

- Ruiz Moreno, Isidoro J., 1934-. La revolución del 55 : dictadura, conspiración y caída de Perón (Cuarta edición ed.). Buenos Aires. ISBN 978-950-620-336-8. OCLC 913745779.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Cichero, Daniel E. (2005). Bombas sobre Buenos Aires : gestación y desarollo del bombardeo aéreo sobre la Plaza de Mayo del 16 de junio de 1955 (1ra. ed.). Barcelona: Vergara Grupo Zeta. ISBN 950-15-2347-0. OCLC 68472301.

- "Douglas DC-3 & C-47 en la Fuerza Aérea Argentina - Avialatina". YouTube. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- Frenkel, Leopoldo. (1992). Juan Ignacio San Martín : el desarrollo de las industrias aeronáutica y automotriz en la Argentina. Germano Artes Gráficas). Buenos Aires: L. Frenkel. p. 41. ISBN 950-43-4267-1. OCLC 27327594.

- "Primer aterrizaje de un Hércules C-130 en Marambio". Archived from the original on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- Marambio Station Archived 2014-01-07 at the Wayback Machine

- "Aniversario Aereo de la Antartida Argentina". Archived from the original on 24 December 2014. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- Twin Otter picture Archived 2011-07-18 at the Wayback Machine

- "The First Three-Continental and Transantarctic Flight". Fin del Mundo. Sitio Oficial de la Provincia de Tierra del Fuego, Antártida e Islas del Atlántico Sur. Archived from the original on 1 October 2013.

- "Primer Vuelo Transantártico Tricontinental. Operación "Transantar" (04 al 10-Oct-1973)" (in Spanish). Fundación Marambio. Archived from the original on 28 February 2009.

- Yofre, Juan Bautista, 1946- (2011). 1982 : los documentos secretos de la guerra de Malvinas-Falklands y el derrumbe del Proceso. Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana. p. 56. ISBN 978-950-07-3666-4. OCLC 764559333.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Quellet 1997, pp. 106-108.

- Quellet 1997, p. 797.

- "1º de Mayo – Bautismo de fuego de la Fuerza Aérea Argentina" (in Spanish). Centro Regional Universitario Cordoba IUA. Retrieved 2020-05-21.

- Fuerza Aerea Argentina (1998) [1983]. Historia de la Fuerza Aérea Argentina. Tomo VI: La Fuerza Aérea en Malvinas. Volumen 1. Dirección de Estudios Históricos. Fuerza Aerea Argentina. ISBN 987-96654-4-9.

- Historia de la Fuerza Aérea Argentina. Ricardo Luis Quellet. [Buenos Aires]: [Fuerza Aérea Argentina, Dirección de Estudios Históricos]. 1998. p. 797. ISBN 987-96654-4-9. OCLC 760500498.CS1 maint: others (link)

- De León, Pablo Gabriel (2017). El proyecto misilístico Cóndor. Su origen, desarrollo y cancelación. Lenguaje Claro. ISBN 978-987-3764-24-0. p. 96.

- "Adiós a la colimba". La Voz (in Spanish). Retrieved 2020-05-21.

- "- Fuerza Area Argentina". Archived from the original on 7 April 2012. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- "VII Brigada Aerea". Archived from the original on 24 December 2007. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- "Kirchner removió al brigadier general Carlos Rodhe". www.lanacion.com.ar (in Spanish). 2005-02-17. Retrieved 2020-05-21.

- "Zona Militar". zonamilitar.com.ar. Archived from the original on 2010-09-03.

- "Iniciativa para reequipar a las FF.AA". Archived from the original on 19 August 2010. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- "Argentina in negotiations for Israeli Kfir fighters". Flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 2015-08-22. Retrieved 2015-08-18.

- Argentina; Spanish Mirage F-1 deal scrapped due to UK preassure Archived 2014-10-29 at the Wayback Machine - Dmilt.com, 7 March 2014

- "Argentina's Jet Fighter Replacement Options Narrow". Defensenews.com. 30 November 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- "Argentina seeks Kfir deal with Israel" Archived 2014-01-18 at the Wayback Machine January 13, 2014

- "Argentina and China agree fighter aircraft working group". IHS Jane's 360. 5 February 2015. Archived from the original on 22 February 2015. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- Porfilio, Gabriel (1 December 2015). "Argentina retires Dassault Mirage fleet". IHS Jane's 360. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- Porfilio, Gabriel (28 January 2016). "Argentinian MoD confirms all fighters grounded". IHS Jane's Defence Weekly. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- Aguilera, Edgardo (27 January 2016). "No queremos una Armada que no navegue ni una Fuerza Aérea que no vuele". Diario Ambito Financiero (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- "La llegada de Obama desnudó la triste realidad de la FAA". El Sol. 21 March 2016. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- https://www.aerotime.aero/clement.charpentreau/25597-argentinian-a-4ar-fighter-jet-crashes-near-cordoba-pilot-dead

- https://www.janes.com/article/89974/argentina-selects-korean-fa-50-fighter

- https://www.shephardmedia.com/news/defence-notes/premium-latin-american-projects-face-covid-19-prob/

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidaxe/2020/10/31/no-fa-50s-for-you-uk-diplomats-swat-down-argentine-fighter-plan/?sh=19263f0318d0

- https://en.mercopress.com/2020/10/31/uk-bars-sale-of-south-korean-fighter-jets-for-the-argentine-air-force

- https://quwa.org/2020/12/06/argentina-will-take-another-look-at-the-jf-17-thunder-2/

- "LEY DE DEFENSA NACIONAL- Título IV". servicios.infoleg.gob.ar. 1988. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- Esteban Brea (4 August 2016). "ORBAT FAA (I): Antecedentes, Brigadas Aéreas, Bases Militares y Escuadrones". Gaceta Aeronáutica. Archived from the original on 23 June 2018. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- AirForces Monthly. Stamford, Lincolnshire, England: Key Publishing Ltd. February 2017. p. 20.

- Esteban Brea (8 August 2016). "ORBAT FAA (II): Institutos de Formación". Gaceta Aeronáutica. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "World Air Forces 2021". FlightGlobal. 4 December 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- "Argentina completes receipt of second batch of Pampa III jets". .janes.com. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- "Fuerza Aerea Argentina T-04". airfleets.net. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- "Fuerza Aerea Argentina Bell 412". Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- "World Air Forces 2020". Flightglobal Insight. 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- "Argentine-Air-Force". helis.com. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- "World Air Forces 2004". Flightglobal Insight. 2004. Archived from the original on 25 October 2014. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- "Fuerza Aerea Argentina VIP S-76". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

Sources

- International Institute for Strategic Studies (2010-02-03). Hackett, James (ed.). The Military Balance 2010. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-85743-557-3.

- Quellet, Ricardo Luis (1997). Historia de la Fuerza Aérea Argentina. [Buenos Aires]: [Fuerza Aérea Argentina, Dirección de Estudios Históricos]. ISBN 987-96654-4-9. OCLC 760500498.

Further reading

- (in Spanish) La Argentina fabricante de Aviones (retrieved 2016-04-23)

External links

- Official website (in Spanish)

- Organization and equipment (in English)