Modern yoga

Modern yoga consists of a range of techniques including asanas (postures) and meditation derived from some of the philosophies, teachings and practices of the Yoga school, which is one of the six schools of traditional Hindu philosophies, and organised into a wide variety of schools and denominations. It has been described by Elizabeth de Michelis as having four types, namely: Modern Psychosomatic Yoga, as in The Yoga Institute; Modern Denominational Yoga, as in Brahma Kumaris; Modern Postural Yoga, as in Iyengar Yoga; and Modern Meditational Yoga, as in early Transcendental Meditation. The yoga scholar Mark Singleton however does not subscribe to De Michelis's framework, considering the categories to "subsume detail, variation, and exception".[1] In the 21st-century, modern yoga has become the subject of academic study. It has adopted innovations from Western gymnastics and other practices.[2][3]

Some versions of modern yoga contain reworkings of the ancient spiritual tradition, and practices vary from wholly secular, for exercise and relaxation, through to undoubtedly spiritual, whether in traditions like Sivananda Yoga or in personal rituals. Modern yoga's relationship to Hinduism is complex and contested; some Christians have challenged its inclusion in school curricula on the grounds that it is covertly Hindu, while the "Take Back Yoga" campaign of Hindu American Foundation has challenged attempts to "airbrush the Hindu roots of yoga" from modern manifestations.[4] Yoga has evolved in many directions in modern times, and people are using it with different combinations of techniques for multiple purposes.

Definition

Elizabeth de Michelis – a scholar credited by Andrea Jain to have started the "modern yoga" typology and studies,[3] defines modern yoga as, "signifying those disciplines and schools which are, to a greater or lesser extent, rooted in South Asian cultural contexts, and which more specifically draw inspiration from certain philosophies, teachings and practices of Hinduism."[5] De Michelis 2004 defined a "typology of Modern Yoga" as seen in the West (she excludes forms seen only in India) starting from Vivekananda's 1896 Raja Yoga, with four subtypes as shown in the table.[6]

| De Michelis Type[6] | Definition[6] | Examples given by De Michelis of "relatively pure contemporary types"[6] |

|---|---|---|

| "Modern Psychosomatic Yoga" | Body-Mind-Spirit training Emphasises practical experience Little restriction on doctrine Practised in a privatised setting | The Yoga Institute, Santa Cruz (Yogendra, 1918) Kaivalyadhama, Lonavla (Kuvalayananda, 1924) Sivananda yoga (Sivananda, Vishnudevananda, etc., 1959) Himalayan Institute (Swami Rama, 1971) |

| "Modern Denominational Yoga" | Neo-Hindu gurus Emphasis on each school's own teachings Own belief system and authorities Cultic environment, sometimes sectarian May use all other forms of Modern Yoga | Brahma Kumaris (Lekhraj Kripalani, 1930s) Sahaja Yoga (Nirmala Srivastava, 1970) ISKCON (A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, 1966) Rajneeshism (Rajneesh, c. 1964) Late Transcendental Meditation |

| "Modern Postural Yoga" | Emphasises asanas (yoga postures) and pranayama | Iyengar Yoga (B. K. S. Iyengar, c. 1966) Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga (Pattabhi Jois, c. 1948) |

| "Modern Meditational Yoga" | Emphasises mental techniques of concentration and meditation | Early Transcendental Meditation (Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, 1950s) Sri Chinmoy, c. 1964 some current Buddhist organisations[lower-alpha 1] |

According to the religious studies scholar Andrea Jain, "Modern yoga refers to a variety of systems that developed as early as the 19th century as a [response to] capitalist production, colonial and industrial endeavors, global developments in areas ranging from metaphysics to fitness, and modern ideas and values." In contemporary practice, modern yoga is prescribed as a part of self-development and is believed to provide "increased beauty, strength, and flexibility as well as decreased stress".[3]

Mark Singleton, a scholar of yoga's history and practices, states that De Michelis's typology provides categories useful as a way into studying yoga in the modern age, but they are not a "good starting point for history insofar as it subsumes detail, variation, and exception".[1] Singleton does not subscribe to this interpretive framework, and considers "modern yoga" to refer to "yoga in the modern age".[1] He questions the typology as follows:

Can we really refer to an entity called Modern Yoga and assume that we are talking about a discrete and identifiable category of beliefs and practices? Does Modern Yoga, as some seem to assume, differ in ontological status (and hence intrinsic value) from "traditional yoga"? Does it represent a rupture in terms of tradition rather than a continuity? And in the plethora of experiments, adaptations, and innovations that make up the field of transnational yoga today, should we be thinking of all these manifestations as belonging to Modern Yoga in any typological sense?

— Mark Singleton[1]

Modern yoga is derived from Haṭha yoga (one aspect of traditional yoga).[7] However, states Singleton, modern yoga represents innovative practices that have taken the Indian heritage, experimented with techniques from non-Indic cultures, and radically evolved it into local forms worldwide.[8][9]

From the 1970s, modern yoga spread across many countries of the world, changing as it did so, and becoming "an integral part of (primarily) urban cultures worldwide", to the extent that the word yoga in the Western world now means the practice of asanas, typically in a class.[lower-alpha 2][10]

Modern transnational yoga is variously viewed through "cultural prisms" including New Age religion, psychology, sports science, medicine,[11] photography,[12] and fashion.[13] Jain states that although "hatha yoga is traditionally believed to be the ur-system of modern postural yoga, equating them does not account for the historical sources". According to her, asanas "only became prominent in modern yoga in the early twentieth century as a result of the dialogical exchanges between Indian reformers and nationalists and Americans and Europeans interested in health and fitness".[14] In short, Jain writes, "modern yoga systems ... bear little resemblance to the yoga systems that preceded them. This is because [both] ... are specific to their own social contexts."[15]

Types of modern yoga

The four types of modern yoga defined by De Michelis are described below.[6]

Modern Psychosomatic Yoga

Modern Psychosomatic Yoga is a form of yoga involving Body-Mind-Spirit training. According to De Michelis, it emphasises practical experience, places relatively little restriction on doctrine, and is practised in a privatised setting.[6] She gives as examples The Yoga Institute at Santa Cruz, India, founded by Yogendra, sometimes called "the Father of the Modern Yoga Renaissance", in 1918;[6][16] Kaivalyadhama Shrimad Madhava Yoga Mandir Samiti at Lonavla, India, founded by Kuvalayananda in 1924; and Sivananda yoga, led by Sivananda but whose asana practice was founded by his disciple Vishnudevananda in 1959; and the Himalayan Institute, founded by Swami Rama in 1971.[6]

Yogendra brought yoga asanas to America, his system influenced by that of Max Müller.[16] Yogendra founded a branch of The Yoga Institute in New York state in 1919, a year after founding the first one in India.[17][18] He secularized yoga, using it in the service of Indian householders with physical complaints.[16][19] The American explorer and author Theos Bernard studied traditional hatha yoga and tantric yoga, travelling to India and Tibet, and publicising these traditions in books such as his 1943 Hatha Yoga: The Report of A Personal Experience.[20][21][22]

In 1924, Kuvalayananda founded the Kaivalyadhama Health and Yoga Research Center in Maharashtra. He emphasized its health benefits. According to the scholar Joseph Alter, he had a "profound" effect on the evolution of asana-based modern yoga.[23][24] The yoga scholar-practitioner Norman Sjoman states that Kuvalayananda attempted to revive or to create a Yoga posture practice in India based on the medieval texts.[20]

In 1925, Paramahansa Yogananda, having moved from India to America, set up the Self-Realization Fellowship in Los Angeles, and taught yoga, including asanas, breathing, chanting and meditation, to "tens of thousands of Americans".[25] In 1923, Yogananda's younger brother, Bishnu Charan Ghosh, founded the Ghosh College of Yoga and Physical Culture in Calcutta; the college taught yoga to Bikram Choudhury, founder of Bikram Yoga.[16]

Krishnamacharya observed the work at Kaivalyadhama in 1934, but while that centre has always attempted to study yoga scientifically, he continued the Mysore Palace tradition of incorporating Western physical training in his form of yoga, rather than seeking to study it as science.[26]

Other Indian schools of yoga took up the new style of asanas, but continued to emphasize Haṭha yoga's spiritual goals and practices to varying extents. The Divine Life Society was founded by Sivananda Saraswati of Rishikesh in 1936. His many disciples include Swami Vishnudevananda, who founded the International Sivananda Yoga Vedanta Centres, starting in 1959; Swami Satyananda of the Bihar School of Yoga, a major centre of Hatha yoga teacher training, founded in 1963;[27][28] and Swami Satchidananda of Integral Yoga, founded in 1966.[27] Vishnudevananda published his influential Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga in 1960.[29][30]

Modern Meditational Yoga

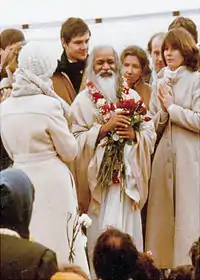

Modern Meditational Yoga emphasises the mental techniques of concentration and meditation.[6] De Michelis gives as examples early Transcendental Meditation as taught by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in the 1950s; the teaching of Sri Chinmoy's yoga centres, from c. 1964; and some Buddhist organisations of the 21st century.[6]

Transcendental Meditation involves the use of a mantra for 15–20 minutes twice per day while sitting with the eyes closed.[31] The technique has been described as both religious and non-religious, as an aspect of a new religious movement, as rooted in Hinduism,[32][33] and as a non-religious practice for self-development.[34]

Sri Chinmoy, an athlete and flautist, advocated meditation both for silent sitting and for use when running, performing music or making artworks, as described in his book 222 Meditation Techniques.[35] He also made use of mantric singing.[36]

Modern Denominational Yoga

Modern Denominational Yoga is a form of yoga centred around Neo-Hindu gurus; each school places emphasis on its own teachings, and provides its own belief system and hierarchy. The environment is cultic, sometimes sectarian. De Michelis states that Modern Denominational Yoga may make use of any other form of modern yoga, for instance sometimes using asana practice and meditation.[6] She gives as examples Brahma Kumaris, founded by Lekhraj Kripalani in the 1930s; Sahaja Yoga, founded by Nirmala Srivastava (known as Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi) in 1970; ISKCON (the International Society for Krishna Consciousness), founded by A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada in 1966; Rajneeshism, founded by Rajneesh, c. 1964; and what she describes as late Transcendental Meditation, as it gained an institutional form.[6]

Brahma Kumaris teaches meditation to purify the self, focusing on the belief that the student's soul is moving towards God. Students sit upright with eyes open, sometimes listening to a text or to some music, often supervised by a guide. The meditation has stages: a preparatory stage with visualisation; consciousness of the soul and of God; concentration on the purity of God; realisation, when the soul is connected with God.[37]

Sahaja Yoga describes itself as "a method of meditation which brings a breakthrough in the evolution of human awareness."[38] It aims for "inner awakening" which it equates to "self realization", enlightenment and liberation (moksha).[38] It states that this can be experienced by anyone who sincerely desires to have it through a sitting meditation, placing the hands on different parts of the body in turn, and that self realization requires the subject to forgive "everyone".[39]

ISKCON describes meditation as having three different forms, namely japa (recitation of the name of God, using a string of beads), kirtan (public singing of the names of God, in particular Hare, Krishna, and Rama, to musical accompaniment), and sankirtan (kirtan in a group).[40]

Rajneeshism involved meditation and living in communities in the countryside, practising free love.[41] Rajneesh advocated dynamic meditation using chaotic breathing and "natural body movements". The meditation had five stages such as "act[ing] out all your madnesses".[42]

Modern Postural Yoga

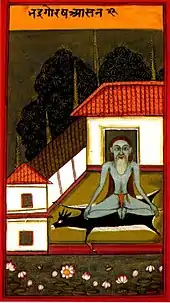

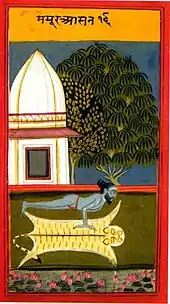

The flowing sequences of salute to the sun, Surya Namaskar, now accepted as yoga and containing popular asanas such as Uttanasana and upward and downward dog poses,[43][44] were popularized by the Rajah of Aundh, Bhawanrao Shrinivasrao Pant Pratinidhi, in the 1920s, though the Rajah denied having invented them.[45][46]

Tirumalai Krishnamacharya (1888–1989), "the father of modern yoga",[47][48] claimed to have spent seven years with one of the few masters of Haṭha yoga then living, Ramamohana Brahmachari, at Lake Manasarovar in Tibet, from 1912 to 1918.[49][50] He studied under Kuvalayananda in the 1930s, creating in his yogashala in the Jaganmohan Palace in Mysore "a marriage of Haṭha yoga, wrestling exercises and modern Western gymnastic movement", states Singleton.[9] The Maharajah of Mysore Krishna Raja Wadiyar IV was a leading advocate of physical culture in India, and a neighbouring hall of his palace was used to teach Surya Namaskar classes, then considered to be gymnastic exercises. Krishnamacharya adapted these sequences of exercises into his flowing style of yoga.[49][51]

Among Krishnamacharya's pupils were people who became influential yoga teachers themselves: the Russian Eugenie V. Peterson, known as Indra Devi (from 1937), who moved to Hollywood, taught yoga to actors and other celebrities, and wrote the bestselling[52] book Forever Young, Forever Healthy;[53] Pattabhi Jois (from 1927), who founded the flowing style Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga whose Mysore style makes use of repetitions of Surya Namaskar, in 1948,[50][54] which in turn led to Power Yoga;[55] B.K.S. Iyengar (from 1933), his brother-in-law, who founded Iyengar Yoga; T.K.V. Desikachar, his son, who continued his Viniyoga tradition; Srivatsa Ramaswami; and A. G. Mohan, co-founder of Svastha Yoga & Ayurveda.[56][57] Together they made yoga popular as physical exercise and brought it to the Western world.[50][54] Iyengar's 1966 book Light on Yoga[58] popularised yoga asanas worldwide with what Sjoman calls its "clear no-nonsense descriptions and the obvious refinement of the illustrations",[59] though the degree of precision it calls for is missing from earlier yoga texts.[60] The tradition begun by Krishnamacharya survives at the Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram in Chennai; his son T. K. V. Desikachar and his grandson Kausthub Desikachar teach in small groups, coordinating asana movements with the breath, and personalising the teaching according to the needs of individual students.[61][62]

Modern postural yoga consists largely but not exclusively of the practice of asanas.[63] There were very few standing asanas before 1900.[64] By 2012, there were at least 19 widespread styles from Ashtanga Yoga to Viniyoga. These emphasise different aspects including aerobic exercise, precision in the asanas, and spirituality in the Haṭha yoga tradition.[61][65] For example, Bikram Yoga has an aerobic exercise style with rooms heated to 105 °F (41 °C) and a fixed pattern of 2 breathing exercises and 26 asanas. Iyengar Yoga emphasises correct alignment in the postures, working slowly, if necessary with props, and ending with relaxation. Sivananda Yoga focuses more on spiritual practice, with 12 basic poses, chanting in Sanskrit, pranayama breathing exercises, meditation, and relaxation in each class, and importance is placed on vegetarian diet.[61][65][66] Jivamukti yoga uses a flowing vinyasa style of asanas accompanied by music, chanting, and the reading of scriptures. Kundalini yoga emphasises the awakening of kundalini energy through meditation, pranayama, chanting, and suitable asanas.[65]

De Michelis theorises that Modern Postural Yoga schools went through three phases of development: popularisation from the 1950s; consolidation from the mid-1970s; and finally acculturation, from the late 1980s. In popularisation, teachers appeared, media such as books and television programmes were created, class attendance rose, and people travelled to India, experiencing yogic ideas for themselves. Since schools were relatively small, contact with teachers was personal and charismatic "gurus" could directly attract pupils. In consolidation, many schools closed, and the remainder became more institutional, with standardised teacher training and certification. In acculturation, governing bodies like the British Wheel of Yoga were given official status, and postural yoga was recommended by health authorities.[67] As evidence for this, she describes the history of Iyengar Yoga with respect to the three phases.[68]

.jpg.webp)

Alongside the yoga brands, many teachers, for example in England, offer an unbranded "hatha yoga",[lower-alpha 3] often mainly to women, creating their own combinations of poses. These may be in flowing sequences (vinyasas), and new variants of poses are often created.[69][70][65] The gender imbalance has sometimes been marked; in Britain in the 1970s, women formed between 70 and 90 percent of most yoga classes, as well as most of the yoga teachers.[71]

Modern postural yoga has been popularized in the Western world by claims about its health benefits.[72] The history of such claims was reviewed by William J. Broad in his 2012 book The Science of Yoga; he argues that while the health claims for yoga began as Hindu nationalist posturing, it turns out that there is[73] "a wealth of real benefits".[73] Among the early exponents was Kuvalayananda, who attempted to demonstrate scientifically in his purpose-built 1924 laboratory at Kaivalyadhama that Sarvangasana (shoulderstand) specifically rehabilitated the endocrine glands (the organs that secrete hormones). He found no evidence to support this claim, for this or any other asana.[74]

Research

Yoga is becoming a subject of academic inquiry. Medknow (part of Wolters Kluwer), with Swami Vivekananda Yoga Anusandhana Samsthana university, publishes the peer-reviewed open access medical journal International Journal of Yoga.[75][76] An increasing number of papers are being published on the possible medical benefits of yoga, such as on stress and low back pain.[77] The School of Oriental and African Studies in London has created a Centre of Yoga Studies; it hosts the Hatha Yoga Project which is tracing the history of physical yoga, and it teaches a master's degree in yoga and meditation.[78]

The philosopher Ernest Wood referred to "modern" yoga in the title of his 1948 book "Practical Yoga, Ancient and Modern".[79] According to Andrea Jain, the study of modern yoga as a "concretized field" began in 2004 with the monograph A History of Modern Yoga by Elizabeth de Michelis.[3] Prior to it, early yoga scholarship such as by Mircea Eliade did not distinguish premodern yoga and modern yoga. The typology of "modern yoga" then did not exist. The monograph by De Michelis, states Andrea Jain, was a groundbreaking work that presented for the first time a fourfold typology comprising "Modern Psychosomatic Yoga, Modern Meditational Yoga, Modern Postural Yoga, and Modern Denominational Yoga".[3]

Mark Singleton, a scholar of Yoga history and practices, states that De Michelis's typology provides useful categories as a way into studying yoga in the modern age, but that it is not a "good starting point for history insofar as it subsumes detail, variation, and exception".[1] Singleton does not subscribe to this interpretive framework, and considers "modern yoga" to refer to "yoga in the modern age".[1] He questions the typology as follows:

Can we really refer to an entity called Modern Yoga and assume that we are talking about a discrete and identifiable category of beliefs and practices? Does Modern Yoga, as some seem to assume, differ in ontological status (and hence intrinsic value) from “traditional yoga”? Does it represent a rupture in terms of tradition rather than a continuity? And in the plethora of experiments, adaptations, and innovations that make up the field of transnational yoga today, should we be thinking of all these manifestations as belonging to Modern Yoga in any typological sense?

— Mark Singleton[1]

According to Ian Whicher, a scholar known for his studies on the Yoga tradition in India, the surviving early texts of pre-modern yoga tend to be similarly redacted and dry, but yoga in its authentic cultural context "has always been an esoteric discipline taught mainly through oral tradition".[80] This practice-based yoga has always manifested in the form of training by gurus to their disciples in India.[80] This emphasis on the transmission of yoga practice through verbal instruction and by direct demonstration has been a historic part of the yoga tradition.[80] According to Singleton, it is an Orientalists' error to rely exclusively on pre-modern textual material that has survived into the modern age, and this "reliance is particularly evident in the scholarship of yoga".[81] The "modern, English-language yoga", states Singleton, is "greatly informed by the textual vision of Orientalist and anglo-Indian scholarship of the late nineteenth century".[82]

Notes

- On page 73, De Michelis refers readers to Gombrich & Obeyesekere 1988 and Sharf 1995 for more on Buddhist contexts.

- De Michelis notes that to speakers of Indic languages, yoga has a "quite different" semantic range, including meditation, prayer, ritual and devotional practices, ethical behaviour, and "secret esoteric techniques" that average English speakers would not consider to be yoga.[10]

- Not to be confused with medieval Haṭha yoga

References

- Singleton 2010, pp. 18–19.

- Singleton 2010, pp. 5 and 82–85, Quote: "Western physical culture–oriented āsana practices, developed in India, subsequently found their way (back) to the West, where they became identified and merged with forms of 'esoteric gymnastics', which had grown popular in Europe and America from the mid-nineteenth century.".

- Jain, Andrea (2016). "Modern Yoga". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.163. ISBN 9780199340378.

- James Mallinson (2013), Yoga and Religion, Heythrop College: A Seminar on Modern yoga, London, UK Hindu Christian Foundation

- De Michelis, Elizabeth (2007-10-16). "A Preliminary Survey of Modern Yoga Studies". Asian Medicine. Brill. 3 (1): 2–3. doi:10.1163/157342107x207182. ISSN 1573-420X. S2CID 72900651.

- De Michelis 2004, pp. 187–189.

- "Yoga". Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

The yoga widely known in the West is based on hatha yoga, which forms one aspect of the ancient Hindu system of religious and ascetic observance and meditation, the highest form of which is raja yoga and the ultimate aim of which is spiritual purification and self-understanding leading to samadhi or union with the divine

- Singleton 2010, pp. 32-33.

- Singleton, Mark (4 February 2011). "The Ancient & Modern Roots of Yoga". Yoga Journal.

- De Michelis, Elizabeth (2007). "A Preliminary Survey of Modern Yoga Studies" (PDF). Asian Medicine, Tradition and Modernity. 3 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1163/157342107X207182.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, p. ix.

- Mastalia 2017.

- Thompson, Derek (28 October 2018). "Everything You Wear Is Athleisure | Yoga pants, tennis shoes, and the 100-year history of how sports changed the way Americans dress". The Atlantic.

Lululemon has sparked a global fashion revolution, sometimes called 'athleisure' or 'activewear,' which has injected prodigious quantities of spandex into modern dress and blurred the lines between yoga-and-spin-class attire and normal street clothes.

- Jain, Andrea R. (2012). "The Malleability of Yoga: A Response to Christian and Hindu Opponents of the Popularization of Yoga". Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies. Butler University, Irwin Library. 25 (1). doi:10.7825/2164-6279.1510.

- Jain 2015, p. 19.

- Newcombe, Suzanne (2017). "The Revival of Yoga in Contemporary India" (PDF). Religion. Oxford Research Encyclopedias. 1. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.253. ISBN 9780199340378.

- Caycedo 1966, p. 194.

- De Michelis 2004, p. 183.

- Singleton 2010, pp. 116–117.

- Sjoman 1999, p. 38.

- Veenhof 2011, p. 396.

- Bernard 2007.

- Alter 2004, p. 31.

- Goldberg 2016, pp. 100–141.

- Ricci, Jeanne (28 August 2007). "Paramahansa Yogananda". Yoga Journal. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- De Michelis 2004, p. 197.

- Mallinson 2011, p. 779.

- Singleton 2010, p. 213, note 14.

- Vishnudevananda 1988.

- Sjoman 1999, pp. 87–89.

- "The Transcendental Meditation Program". Tm.org. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- Bainbridge, William Sims (1997). The Sociology of Religious Movements. New York: Routledge. p. 188. ISBN 0-415-91202-4.

- Aghiorgoussis, Maximos (Spring 1999). "The challenge of metaphysical experiences outside Orthodoxy and the Orthodox response". Greek Orthodox Theological Review. 44 (1–4): 21, 34.

- Chryssides, George D. (2001). Exploring New Religions. Continuum International Publishing. pp. 301–303. ISBN 978-0826459596."Although one can identify the Maharishi's philosophical tradition, its teachings are in no way binding on TM practitioners. There is no public worship, no code of ethics, no scriptures to be studied, and no rites of passage that are observed, such as dietary laws, giving to the poor, or pilgrimages. In particular, there is no real TM community: practitioners do not characteristically meet together for public worship, but simply recite the mantra, as they have been taught it, not as religious obligation, but simply as a technique to benefit themselves, their surroundings and the wider world."

- Sri Chinmoy (2016). 222 Meditation Techniques. Golden Shore. ISBN 978-3895322877.

- "Meditation". Sri Chinmoy Centre. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- Kranenborg, Reender (1999). "Brahma Kumaris: A New Religion?". CESNUR center for studies on new religions.

- "About Sahaja Yoga". Sahaja Yoga. 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- "Experience Your Self Realization". Sahaja Yoga. 2013.

- "Meditation". ISKCON. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- Wigington, Patti (6 June 2018). "What Was the Rajneesh Movement?". Learn Religions. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- "Osho Dynamic | An Active Meditation in Five Stages". Osho Dynamic. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- Mehta 1990, pp. 146-147.

- Lidell 1983, pp. 34-35.

- Pant & Morgan 1938.

- Goldberg 2016, pp. 180–207.

- Mohan, A. G.; Mohan, Ganesh (29 November 2009). "Memories of a Master". Yoga Journal. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Anderson, Diane (9 August 2010). "The YJ Interview: Partners in Peace". Yoga Journal. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Singleton 2010, pp. 175-210.

- Pages Ruiz, Fernando (28 August 2007). "Krishnamacharya's Legacy: Modern Yoga's Inventor". Yoga Journal. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- Goldberg 2016, pp. 234–248.

- Schrank, Sarah (2014). "American Yoga: The Shaping of Modern Body Culture in the United States". American Studies. 53 (1): 169–182. doi:10.1353/ams.2014.0021. S2CID 144698814.

- Devi 1953.

- Singleton 2010, pp. 88, 175-210.

- Kest, Bryan. "The History of Power Yoga". Power Yoga. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- Iyengar 2006, pp. xvi–xx.

- Mohan 2010, p. 11.

- Iyengar 1979.

- Sjoman 1999, p. 39.

- Sjoman 1999, p. 47.

- YJ Editors (13 November 2012). "What's Your Style? Explore the Types of Yoga". Yoga Journal.

- "Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram". Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- Singleton 2010, pp. 29, 170.

- Singleton 2010, p. 29.

- Beirne, Geraldine (10 January 2014). "Yoga: a beginner's guide to the different styles". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- Goldberg 2016, pp. 320–336.

- De Michelis 2004, pp. 191–194.

- De Michelis 2004, pp. 194–207.

- Singleton 2010, p. 152.

- Cook, Jennifer (28 August 2007). "Find Your Match Among the Many Types of Yoga". Yoga Journal.

If you are browsing through a yoga studio's brochure of classes and the yoga offered is simply described as "hatha," chances are the teacher is offering an eclectic blend of two or more of the styles described above.

- Newcombe, Suzanne (2007). "Stretching for Health and Well-Being: Yoga and Women in Britain, 1960–1980". Asian Medicine. 3 (1): 37–63. doi:10.1163/157342107X207209.

- "Yoga Health Benefits: Flexibility, Strength, Posture, and More". WEBMD. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- Broad 2012, pp. 39 and whole book.

- Goldberg 2016, pp. 100–109, esp. p 108.

- "About Us". International Journal of Yoga. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- "International Journal of Yoga". Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- "The science of yoga — what research reveals". Elsevier. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- "Centre of Yoga Studies". SOAS. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- Wood 2015.

- Alter 2004, pp. 4–5, 21–22.

- Singleton 2010, pp. 12.

- Singleton 2010, pp. 12, 176–177.

Sources

- Alter, Joseph (2004). Yoga in modern India : the body between science and philosophy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11874-1. OCLC 53483558.

- Bernard, Theos (2007) [1943]. Hatha Yoga: The Report of A Personal Experience. Harmony. ISBN 978-0-9552412-2-2. OCLC 230987898.

- Broad, William J. (2012). The Science of Yoga: The Risks and the Rewards. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1451641424.

- Caycedo, Alfonso (1966). India of Yogis. National Publishing House, University of Michigan.

- De Michelis, Elizabeth (2004). A History of Modern Yoga : Patañjali and Western Esotericism. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-8772-8. OCLC 51942410.

- Devi, Indra (1953). Forever Young, Forever Healthy:Simplified Yoga for Modern Living. Prentice-Hall. OCLC 652377847.

- Goldberg, Elliott (2016). The Path of Modern Yoga : the history of an embodied spiritual practice. Inner Traditions. ISBN 978-1-62055-567-5. OCLC 926062252.

- Iyengar, B. K. S. (1979) [1966]. Light on Yoga: Yoga Dipika. Unwin Paperbacks. ISBN 978-1855381667.

- ——— (2006). Light on Life: The Yoga Journey to Wholeness, Inner Peace, and Ultimate Freedom. ISBN 978-1594865244.

- Jain, Andrea (2015). Selling Yoga : from Counterculture to Pop culture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-939024-3. OCLC 878953765.

- Lidell, Lucy; The Sivananda Yoga Centre (1983). The Book of Yoga: the complete step-by-step guide. Ebury. ISBN 978-0-85223-297-2. OCLC 12457963.

- ——— (2011). Knut A. Jacobsen; et al. (eds.). Haṭha Yoga in the Brill Encyclopedia of Hinduism. 3. Brill Academic. pp. 770–781. ISBN 978-90-04-27128-9.

- ——— & Singleton, Mark (2017). Roots of Yoga. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-241-25304-5. OCLC 928480104.

- Mastalia, Francesco (2017). Yoga : the secret of life. Powerhouse Books. ISBN 978-1-57687-856-9. OCLC 971079999.

- Mehta, Silva; Mehta, Mira; Mehta, Shyam (1990). Yoga: The Iyengar Way. Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-0863184208.

- Mohan, A. G. (2010). Krishnamacharya: His Life and Teachings. Shambhala. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-59030-800-4.

- Pant, Pratinidhi; Morgan, Louise (1938) [1929]. The Ten-Point Way to Health = Surya Namaskars... Edited with an introduction by Louise Morgan. J. M. Dent.

- Singleton, Mark (2010). Yoga Body : the origins of modern posture practice. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539534-1. OCLC 318191988.

- Sjoman, Norman E. (1999) [1996]. The Yoga Tradition of the Mysore Palace (2nd ed.). Abhinav Publications. ISBN 81-7017-389-2.

- Veenhof, Douglas (2011). White Lama: The Life of Tantric Yogi Theos Bernard, Tibet's Emissary to the New World. Harmony Books. ISBN 978-0385514323.

- Vishnudevananda, Swami (1988) [1960]. The Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0-517-88431-3.

- Wood, Ernest E. (2015) [1948]. Practical yoga, ancient and modern : being a new, independent translation of Patanjali's yoga aphorisms interpreted in the light of ancient and modern psychological knowledge and practical experience. Josephs Press [Wilshire Book Co, Rider and Co]. ISBN 978-1-4465-2820-4. OCLC 285464424.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Modern yoga. |

- Modern Yoga Research website, managed by SOAS's Elizabeth De Michelis, Suzanne Newcombe, and Mark Singleton

- What's behind the five popular yoga poses loved by the world? - a BBC Seriously... program and web page by Mukti Jain Campion

_from_Jogapradipika_1830_(detail).jpg.webp)