Atlantic Charter

The Atlantic Charter was a statement issued on 14 August 1941 that set out American and British goals for the world after the end of World War II.

| Atlantic Conference Codename: Riviera | |

|---|---|

Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill at the Atlantic Conference | |

| Host country | |

| Date | 9–12 August 1941 |

| Venue(s) | Naval Station Argentia, Placentia Bay |

| Participants | |

| Follows | First Inter-Allied Meeting |

| Precedes | Second Inter-Allied Meeting |

| Key points | |

Atlantic Charter | |

The joint statement, later dubbed the Atlantic Charter, outlined the aims of the United States and the United Kingdom for the postwar world as follows: no territorial aggrandizement, no territorial changes made against the wishes of the people (self-determination), restoration of self-government to those deprived of it, reduction of trade restrictions, global cooperation to secure better economic and social conditions for all, freedom from fear and want, freedom of the seas, and abandonment of the use of force, and disarmament of aggressor nations. The adherents to the Atlantic Charter signed the Declaration by United Nations on 1 January 1942, which was the basis for the modern United Nations.

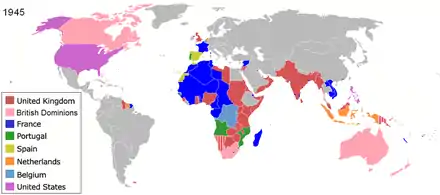

The Atlantic Charter inspired several other international agreements and events that followed the end of the war. The dismantling of the British Empire, the formation of NATO, and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) all derived from the Atlantic Charter.

Background

The Allies first expressed their principles and vision for the post-World War II world in the Declaration of St. James's Palace in June 1941.[1] The Anglo-Soviet Agreement was signed in July 1941 forming an alliance between the two countries.

US President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill discussed what would become the Atlantic Charter in 1941 during the Atlantic Conference in Placentia Bay, Newfoundland.[2] They made their joint declaration on 14 August 1941 from the US naval base on the bay, Naval Base Argentia, which had recently been leased from Britain as part of a deal that saw the Americans give 50 surplus destroyers to British for use against German U-boats although the United States did not enter the war as a combatant until the attack on Pearl Harbor four months later.

Since the policy was issued as a statement, there was no formal, legal document called "Atlantic Charter." It detailed goals and aims for the war and the postwar world.

Many of the ideas of the charter came from an ideology of Anglo-American internationalism that sought British and American co-operation for international security.[3] Roosevelt's attempts to tie Britain to concrete war aims and Churchill's desperation to bind the United States to the war effort helped provide motivations for the meeting that produced the Atlantic Charter. It was then assumed at the time that Britain and America would have an equal role to play in any postwar international organization that would be based on the principles of the Atlantic Charter.[4]

Churchill and Roosevelt began communicating in 1939, the first of their 11 meetings during the war.[lower-alpha 1][5] Both men traveled in secret; Roosevelt was on a ten-day fishing trip.[6] On 9 August 1941, the British battleship HMS Prince of Wales steamed into Placentia Bay, with Churchill on board, and met the American heavy cruiser USS Augusta, where Roosevelt and members of his staff were waiting. On first meeting, Churchill and Roosevelt were silent for a moment until Churchill said, "At long last, Mr. President." Roosevelt replied, "Glad to have you aboard, Mr. Churchill."

Churchill then delivered a letter from King George VI to the president and made an official statement, which, despite two attempts, a movie sound crew that was present failed to record.[7]

Content and analysis

.jpg.webp)

The Atlantic Charter made it clear that the United States supported Britain in the war. Both wanted to present their unity regarding their mutual principles and hopes for a peaceful postwar world and the policies that they agreed to follow once Germany had been defeated.[8] A fundamental aim was to focus on the peace that would follow, not specific American involvement and war strategy, although American involvement appeared increasingly likely.[9]

There were eight principal clauses of the charter:

- No territorial gains were to be sought by the United States or the United Kingdom.

- Territorial adjustments must be in accord with the wishes of the peoples concerned.

- All people had a right to self-determination.

- Trade barriers were to be lowered.

- There was to be global economic co-operation and advancement of social welfare.

- The participants would work for a world free of want and fear.

- The participants would work for freedom of the seas.

- There was to be disarmament of aggressor nations and a common disarmament after the war.

The third clause clearly stated that all peoples have the right to decide their form of government but failed to say what changes are necessary in both social and economic terms to achieve freedom and peace.[10]

The fourth clause, with respect to international trade, consciously emphasized that both "victor [and] vanquished" would be given market access "on equal terms." That was a repudiation of the punitive trade relations that had been established within Europe after World War I, as exemplified by the Paris Economy Pact.

Only two clauses expressly discuss national, social, and economic conditions that would be necessary after the war, despite their significance.

Origin of name

When it was released to the public on August 14, 1941,[11] the charter was titled "Joint Declaration by the President and the Prime Minister" and was generally known as the "Joint Declaration." The Labour Party newspaper Daily Herald coined the name Atlantic Charter, but Churchill used it in Parliament on 24 August 1941, which has since been generally adopted.[12]

No signed version ever existed. The document was threshed out through several drafts, and the final agreed text was telegraphed to London and Washington, DC. Roosevelt gave Congress the charter's content on 21 August 1941.[13] He later said, "There isn't any copy of the Atlantic Charter, so far as I know. I haven't got one. The British haven't got one. The nearest thing you will get is the [message of the] radio operator on Augusta and Prince of Wales. That's the nearest thing you will come to it.... There was no formal document."[5]

The British War Cabinet replied with its approval and a similar acceptance was telegraphed from Washington. During the process, an error crept into the London text, but it was subsequently corrected. The account in Churchill's The Second World War concluded, "A number of verbal alterations were agreed, and the document was then in its final shape." It made no mention of any signing or ceremony. Churchill's account of the Yalta Conference quoted Roosevelt saying of the unwritten British constitution that "it was like the Atlantic Charter – the document did not exist, yet all the world knew about it. Among his papers he had found one copy signed by himself and me, but strange to say both signatures were in his own handwriting."[14]

Acceptance by Inter-Allied Council and United Nations

The Allied nations, who had met in June, and leading organizations quickly and widely endorsed the charter.[15] At the subsequent meeting of the Inter-Allied Council in London on 24 September 1941, the governments-in-exile of Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Greece, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, and Yugoslavia, together with the Soviet Union and representatives of the Free French Forces, unanimously adopted adherence to the common principles of policy set forth by Britain and United States.[16] On 1 January 1942, a larger group of nations, which adhered to the principles of the Atlantic Charter, issued a joint Declaration by United Nations, which stressed their solidarity in the defence against Hitlerism.[17]

Impact on Axis powers

The Axis powers, particularly Japan, interpreted the diplomatic agreements as a potential alliance against them. In Tokyo, the Atlantic Charter rallied support for the militarists in the Japanese government, which pushed for a more aggressive approach against the United States and Britain.

The British dropped millions of flysheets over Germany to allay fears of a punitive peace that would destroy the German state. The text cited the charter as the authoritative statement of the joint commitment of Britain and the United States "not to admit any economical discrimination of those defeated" and promised that "Germany and the other states can again achieve enduring peace and prosperity."[18]

The most striking feature of the discussion was that an agreement had been made between a range of countries that held diverse opinions, which accepted that internal policies were relevant to the international problem.[19] The agreement proved to be one of the first steps towards the formation of the United Nations.

Impact on imperial powers and imperial ambitions

The problems came not from Germany and Japan but from those of the allies that had empires and resisted self-determination, especially the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, and the Netherlands. Initially, Roosevelt and Churchill appeared to have agreed that the third point of Charter would not apply to Africa and Asia. However, Roosevelt's speechwriter, Robert E. Sherwood, noted that "it was not long before the people of India, Burma, Malaya, and Indonesia were beginning to ask if the Atlantic Charter extended also to the Pacific and to Asia in general." With a war that could be won only with the help of those allies, Roosevelt's solution was to put some pressure on Britain but to postpone the issue of self-determination of the colonies until after the war.[20]

British Empire

Public opinion in Britain and the Commonwealth was delighted with the principles of the meetings but disappointed that the US was not entering the war. Churchill admitted that he had hoped that the US would decide to commit itself.

The acknowledgement that all people had a right to self-determination gave hope to independence leaders in British colonies.[21]

The Americans insisted that the charter was to acknowledge that the war was being fought to ensure self-determination.[22] The British were forced to agree to these aims, but in a September 1941 speech, Churchill stated that the Charter was meant to apply only to states under German occupation and certainly not to those that were part of the British Empire.[23]

Churchill rejected its universal applicability when it came to the self-determination of subject nations such as British India. Mahatma Gandhi in 1942 wrote to Roosevelt: "I venture to think that the Allied declaration that the Allies are fighting to make the world safe for the freedom of the individual and for democracy sounds hollow so long as India and for that matter Africa are exploited by Great Britain...."[24] Self-determination was Roosevelt's guiding principle, but he was reluctant to place pressure on the British in regard to India and other colonial possessions, as they were fighting for their lives in a war that the United States was not officially participating.[25] Gandhi refused to help the British or the American war effort against Germany and Japan in any way, and Roosevelt chose to back Churchill.[26] India already contributed significantly to the war effort by sending over 2.5 million men, the largest volunteer force in the world, to fight for the Allies, mostly in West Asia and North Africa.[27]

Poland

Churchill was unhappy with the inclusion of references to the right to "self-determination" and stated that he considered the Charter an "interim and partial statement of war aims designed to reassure all countries of our righteous purpose and not the complete structure which we should build after the victory." An office of the Polish government-in-exile wrote to warn Władysław Sikorski that if the charter was implemented with regard to national self-determination, it would prevent the desired Polish annexation of Danzig, East Prussia and parts of German Silesia, which led the Poles to approach Britain to ask for a flexible interpretation of the charter.[28]

Baltic states

During the war, Churchill argued for an interpretation of the charter that would allow the Soviet Union to continue to control the Baltic states, an interpretation that was rejected by the United States until March 1944.[29] Lord Beaverbrook warned that the Atlantic Charter "would be a menace to our [Britain's] own safety as well as to that of the Soviet Union." The United States refused to recognize the Soviet takeover of the Baltic states but did not press the issue against Stalin while he was fighting the Germans.[30] Roosevelt planned to raise the Baltic issue after the war, but he died in April 1945, before the fighting had ended in Europe.[31]

Participants

The participants in the conference were:[32]

- President Franklin D. Roosevelt

- Admiral Ernest J. King, US Navy

- Admiral Harold R. Stark, US Navy

- General George C. Marshall, US Army

- Presidential adviser Harry Hopkins

- Prime Minister Winston Churchill

- General Sir John Dill, British Army

- Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, Royal Navy

See also

Notes

Footnotes

- However, it was not their first meeting. They had attended the same dinner at Gray's Inn on 29 July 1918.

Citations

- "1941: The Declaration of St. James' Palace". United Nations. 25 August 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- Langer and Gleason, chapter 21

- Cull, pp. 4, 6

- Cull, pp 15, 21.

- Gunther, pp. 15–16

- Weigold, pp. 15–16

- Gratwick, p. 72

- Stone, p. 5

- O'Sullivan and Welles

- Stone, p. 21

- "Milestones: 1937–1945". history.state.gov. Office of the Historian, U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- Wrigley, p. 29

- "President Roosevelt's message to Congress on the Atlantic Charter". The Avalon Project. Lillian Goldman Law Library. 21 August 1941. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- Churchill, p. 393

- Lauren, pp. 140–41

- "Inter-Allied Council Statement on the Principles of the Atlantic Charter". The Avalon Project. Lillian Goldman Law Library. 24 September 1941. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Joint Declaration by the United Nations". The Avalon Project. Lillian Goldman Law Library. 1 January 1942. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- Sauer, p. 407

- Stone, p. 80

- Borgwardt, p. 29

- Bayly and Harper

- Louis (1985) pp. 395–420

- Crawford, p. 297

- Sathasivam, p. 59

- Joseph P. Lash, Roosevelt and Churchill, 1939-1941, W. W. Norton & Company, New York, 1976, pp. 447–448.

- Louis, (2006), p. 400

- "Second World War Memorials". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Archived from the original on 2 January 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- Prażmowska, p. 93

- Whitcomb, p. 18;

- Louis (1998), p. 224

- Hoopes and Brinkley, p. 52

- http://www.history.navy.mil/photos/sh-fornv/uk/uksh-p/pow12.htm

Bibliography

- Bayly, C.; Harper, T. (2004). Forgotten Armies: The Fall of British Asia, 1941–1945. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. ISBN 9780674017481.

- Beschloss, Michael R. (2003). The Conquerors: Roosevelt, Truman and the Destruction of Hitler's Germany, 1941–1945. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780743244541.

- Borgwardt, Elizabeth (2007). A new deal for the world: America's vision for human rights. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674281912.

- Brinkley, Douglas G.; Facey-Crowther, David, eds. (1994). The Atlantic Charter. Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780312089306.

- Charmley, John (2001). "Churchill and the American Alliance". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. Sixth Series 11: 353–371. ISSN 0080-4401. JSTOR 3679428.

- Churchill, Winston (2010). Triumph and Tragedy: The Second World War. RosettaBooks. ISBN 9780795311475.

- Crawford, Neta C. (2002). Argument and Change in World Politics: Ethics, Decolonization, and Humanitarian Intervention. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521002790.)

- Cull, Nicholas (March 1996). "Selling peace: the origins, promotion and fate of the Anglo-American new order during the Second World War". Diplomacy and Statecraft. 7 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1080/09592299608405992.

- Gratwick, Harry (2009). Penobscot Bay: People, Ports & Pastimes. The History Press. ISBN 9781596296237.

- Gunther, John (1950). Roosevelt in retrospect: a profile in history. New York: Harper & Brothers.

- Hein, David (July 2013). "Vulnerable: HMS Prince of Wales in 1941". Journal of Military History. 77 (3).

- Jordan, Jonathan W. (2015), American Warlords: How Roosevelt's High Command Led America to Victory in World War II (NAL/Caliber 2015).

- Hoopes, Townsend; Brinkley, Douglas (2000). FDR and the Creation of the U.N. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300085532.

- Kimball, Warren (1997). Forged in war: Churchill, Roosevelt and the Second World War. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 9780062034847.

- Langer, William L.; Gleason, S. Everett (1953). The Undeclared War 1940–1941: The World Crisis and American Foreign Policy. Harper & Brothers. ISBN 978-1258766986.

- Lauren, Paul Gordon (2011). The Evolution of International Human Rights: Visions Seen. U of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0812221381.

- Louis, William Roger (Summer 1985). "American Anti-Colonialism and the Dissolution of the British Empire". International Affairs. 61 (3): 395–420. ISSN 0020-5850. JSTOR 2618660.

- Louis, William Roger (2006). Ends of British Imperialism: The Scramble for Empire, Suez and Decolonization. London: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781845113476.

- Louis, William Roger (1998). More adventures with Britannia: Personalities, Politics and Culture in Britain. London: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781860642937.

- O'Sullivan, Christopher D. (2008). Sumner Welles, Post-War Planning and the Quest for a New World Order 1937–1943. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231142588.

- Prażmowska, Anita (1995). Britain and Poland, 1939–1943: the betrayed ally. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521483858.

- Sauer, Ernst (1955). Grundlehre des Völkerrechts, 2nd edition (in German). Cologne: Carl Heymanns.

- Smith, Jean Edward (2008). FDR. New York: Random House LLC. ISBN 9780812970494.

- Sathasivam, Kanishkan (2005). 'Uneasy Neighbors: India, Pakistan, and US Foreign Policy. Surrey, UK: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 9780754637622.

- Stone, Julius (June 1942). "Peace Planning and the Atlantic Charter". Australian Quarterly. 14 (2): 5–22. ISSN 0005-0091. JSTOR 20631017.

- Whitcomb, Roger S. (1998). The Cold War in Retrospect: The Formative Years. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 9780275962531.

- Weigold, Auriol (2008). Churchill, Roosevelt and India: Propaganda During World War II. Taylor & Francis US. ISBN 9780203894507.

- Wrigley, Chris (2002). Winston Churchill: A Biographical Companion. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780874369908.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Atlantic Charter. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- BBC News

- The Atlantic Conference from the Avalon Project

- Letter from The Ambassador Patrick J. Hurley to the US Secretary of State TEHRAN, 14 April 1945. Describing meeting with Churchill, where Churchill vehemently states that the UK is in no way bound to the principles of the Atlantic Charter.

- The Atlantic Charter