Executive Office of the President of the United States

The Executive Office of the President (EOP) comprises the offices and agencies[2] that support the work of the president at the center of the executive branch of the United States federal government. The EOP consists of several offices and agencies, such as the White House Office (the staff working directly for and reporting to the president, including West Wing staff and the president's closest advisers), the National Security Council, and the Office of Management and Budget.

Seal of the Executive Office | |

Flag of the Executive Office | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | July 1, 1939 |

| Jurisdiction | U.S. Federal Government |

| Headquarters | White House, Washington, D.C. |

| Employees | 4,000 (approximately) |

| Annual budget | $714 million[1] |

| Agency executive | |

| Website | www.whitehouse.gov |

The EOP is also referred to as a "permanent government", with many policy programs, and the people who implement them, continuing between presidential administrations. This is because there is a need for qualified, knowledgeable civil servants in each office or agency to inform new politicians.[3]

The civil servants who work in the Executive Office of the President are also regarded as nonpartisan and politically neutral, so that they can give impartial advice.[3]

With the increase in technological and global advancement, the size of the White House staff has increased to include an array of policy experts to effectively address various fields. There are about 4,000 positions in the EOP, most of which do not require confirmation from the U.S. Senate.

The EOP is overseen by the White House chief of staff. Since January 20, 2021, that position has been held by Ron Klain, who was appointed by Joe Biden, the president of the United States.[4][5][6][7]

History

In 1937, the Brownlow Committee, which was a presidentially commissioned panel of political science and public administration experts, recommended sweeping changes to the executive branch of the United States government, including the creation of the Executive Office of the President. Based on these recommendations, President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1939 lobbied Congress to approve the Reorganization Act of 1939. The Act led to Reorganization Plan No. 1,[8] which created the EOP,[9] which reported directly to the president. The EOP encompassed two subunits at its outset: the White House Office (WHO) and the Bureau of the Budget, the predecessor to today's Office of Management and Budget, which had been created in 1921 and originally located in the Treasury Department. It absorbed most of the functions of the National Emergency Council.[10] Initially, the new staff system appeared more ambitious on paper than in practice; the increase in the size of the staff was quite modest at the start. However, it laid the groundwork for the large and organizationally complex White House staff that would emerge during the presidencies of Roosevelt's successors.[11]

Roosevelt's efforts are also notable in contrast to those of his predecessors in office. During the 19th century, presidents had few staff resources. Thomas Jefferson had one messenger and one secretary at his disposal, both of whose salaries were paid by the president personally. It was not until 1857 that Congress appropriated money ($2,500) for the hiring of one clerk. By Ulysses S. Grant's presidency (1869–1877), the staff had grown to three. By 1900, the White House staff included one "secretary to the president" (then the title of the president's chief aide), two assistant secretaries, two executive clerks, a stenographer, and seven other office personnel. Under Warren G. Harding, there were thirty-one staff, although most were clerical positions. During Herbert Hoover's presidency, two additional secretaries to the president were added by Congress, one of whom Hoover designated as his press secretary. From 1933 to 1939, as he greatly expanded the scope of the federal government's policies and powers in response to the Great Depression, Roosevelt relied on his "brain trust" of top advisers, who were often appointed to vacant positions in agencies and departments, from which they drew their salaries since the White House lacked statutory or budgetary authority to create new staff positions.

After World War II, in particular during the presidency of Dwight David Eisenhower, the staff was expanded and reorganized. Eisenhower, a former U.S. Army general, had been Supreme Allied Commander during the war, and reorganized the Executive Office to suit his leadership style.[12]

Today, the staff is much bigger. Estimates indicate some 3,000 to 4,000 persons serve in EOP staff positions with policy-making responsibilities, with a budget of $300 to $400 million (George W. Bush's budget request for Fiscal Year 2005 was for $341 million in support of 1,850 personnel).[13]

Some observers have noted a problem of control for the president due to the increase in staff and departments, making coordination and cooperation between the various departments of the Executive Office more difficult.[14]

Organization

The president had the power to reorganize the Executive Office due to the 1949 Reorganization Act which gave the president considerable discretion, until 1983 where it was renewed due to President Nixon's administration encountering "disloyalty and obstruction".[14]

The chief of staff is the head of the Executive Office and can therefore ultimately decide what the president needs to deal with personally and what can be dealt with by other staff, in order to avoid wasting the time of the president.

Senior staff within the Executive Office of the President have the title Assistant to the President, second-level staff have the title Deputy Assistant to the President, and third-level staff have the title Special Assistant to the President.[15]

The core White House staff appointments, and most Executive Office officials generally, are not required to be confirmed by the U.S. Senate, although there are a handful of exceptions (e.g., the director of the Office of Management and Budget, the chair and members of the Council of Economic Advisers, and the United States Trade Representative).

The information in the following table is current as of January 20, 2021. Only principal executives are listed; for subordinate officers, see individual office pages.

White House offices

The White House Office (including its various offices listed below) is a sub-unit of the Executive Office of the President (EOP). The various agencies of the EOP are listed above.

- Office of the Chief of Staff

- Office of the National Security Advisor

- Domestic Policy Council

- National Economic Council

- Office of American Innovation

- Office of Cabinet Affairs

- Office of Communications

- Office of Information Technology

- Office of Digital Strategy

- Office of the First Lady

- Office of Intergovernmental Affairs

- Office of Legislative Affairs

- Office of Management and Administration

- Office of Political Affairs

- Office of Presidential Personnel

- Office of Public Liaison

- Office of Scheduling and Advance

- Office of the Staff Secretary

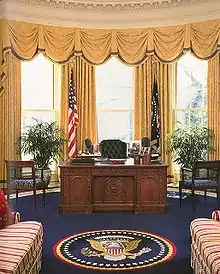

- Oval Office Operations

- White House Counsel

- White House Presidential Personnel Office

- White House Military Office

Congress

Congress as well as the president has some control over the Executive Office of the President. Some of this authority stems from its appropriation powers given by the Constitution, such as the "power of the purse", which affects the Office of Management and Budget and the funding of the rest of federal departments and agencies. Congress also has the right to investigate the operation of the Executive Office, normally holding hearings bringing forward individual personnel to testify before a congressional committee.[3]

The Executive Office often helps with legislation by filling in specific points understood and written by experts, as Congressional legislation sometimes starts in broad terms.[3]

Executive role in "checks and balances" system

The United States Constitution provides checks and balances for the U.S. government through the separation of powers between its three branches: the legislative branch, the executive branch, and the judicial branch.

The executive branch gives veto power to the president, allowing the president to keep the legislative branch in check. The legislative branch can overturn a president's veto with a two-thirds "supermajority" vote by both houses of Congress. The executive branch can also declare executive orders, effectively proclaiming how certain laws should be enforced. This can be checked by the judicial branch however who can deem these orders to be unconstitutional.[19]

Occasionally scholars have suggested the Executive Office has too much influence in the process of checks and balances. Scholar Matthew C. Waxman stated that the ‘executive possess significant informational and operational advantages’ and that the role that congress members face in scrutinizing the executive is ‘insufficient to the task’.[20] He believes that the executive can exert influential pressure over Congress due to the massive public image the role of being the executive has on a nation. The president can portray the legislature or judiciary negatively if they don't follow the executive's agenda. President Trump, in relation to his impeachment, arguably used this implied 'executive power' by criticising the legislature. Trump suggested that the Democrats within the legislature would "badly fail at the voting booth" and stated that the "attempted impeachment" was nothing more than an illegal, partisan coup."[21]

Budget history

This table specifies the budget of the Executive Office for the years 2008-2017, and the actual outlays for the years 1993-2007.

| Year | Budget |

|---|---|

| 2017 | $714 million[1] |

| 2016 | $692 million[22] |

| 2015 | $676 million[23] |

| 2014 | $624 million[24] |

| 2013 | $650 million[25] |

| 2012 | $640 million[26] |

| 2011 | $708 million[27] |

| 2010 | $772 million[28] |

| 2009 | $728 million[29] |

| 2008 | $682 million[30] |

| 2007 | $2956 million[31] |

| 2006 | $5379 million[31] |

| 2005 | $7686 million[31] |

| 2004 | $3349 million[31] |

| 2003 | $386 million[31] |

| 2002 | $451 million[31] |

| 2001 | $246 million[31] |

| 2000 | $283 million[31] |

| 1999 | $417 million[31] |

| 1998 | $237 million[31] |

| 1997 | $221 million[31] |

| 1996 | $202 million[31] |

| 1995 | $215 million[31] |

| 1994 | $231 million[31] |

| 1993 | $194 million[31] |

See also

Notes

- shares staff with the National Security Council

- reports to the National Security Advisor

References

- "FY 2017 Omnibus Summary – Financial Services and General Government Appropriations" (PDF). House Appropriations Committee. May 1, 2017. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- Harold C. Relyea (November 26, 2008). The Executive Office of the President: A Historical Overview (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- Mckeever, Robert J. (July 22, 2014). A Brief Introduction to US Politics. doi:10.4324/9781315837260. ISBN 9781315837260.

- Hartnett, Cass. "Library Guides: United States Federal Government Resources: The Executive Office of the President". guides.lib.uw.edu. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- Trump, Donald J. (December 14, 2018). "I am pleased to announce that Mick Mulvaney, Director of the Office of Management & Budget, will be named Acting White House Chief of Staff, replacing General John Kelly, who has served our Country with distinction. Mick has done an outstanding job while in the Administration..." @realDonaldTrump. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- Swanson, Ian (December 14, 2018). "Trump names Mulvaney acting chief of staff". TheHill. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- O'Toole, Molly (December 30, 2018). "John F. Kelly says his tenure as Trump's chief of staff is best measured by what the president did not do". latimes.com. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- Roosevelt, Franklin D. (April 25, 1939). "Message to Congress on the Reorganization Act". John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. The American Presidency Project. Santa Barbara: University of California. Retrieved May 6, 2011.

- Mosher, Frederick C. (1975). American Public Administration: Past, Present, Future (2nd ed.). Birmingham: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-4829-8.

- Roosevelt, Franklin D. (May 9, 1939). "Message to Congress on Plan II to Implement the Reorganization Act". John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. The American Presidency Project. Santa Barbara: University of California. Retrieved May 6, 2011.

The plan provides for the abolition of the National Emergency Council and the transfer to the Executive Office of the President of all its functions with the exception of the film and radio activities which go to the Office of Education.

- Relyea, Harold C. (March 17, 2008). "The Executive Office of the President: An Historical Overview" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved April 14, 2008.

- Patterson, Bradley H. (1994). "Teams and Staff: Dwight Eisenhower's Innovations in the Structure and Operations of the Modern White House". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 24 (2): 277–298. JSTOR 27551241.

- Burke, John P. "Administration of the White House". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Archived from the original on November 17, 2010. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- Ashbee, Edward, author. (June 17, 2019). US politics today. ISBN 9781526124517. OCLC 1108740337.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Kumar, Martha Joynt. "Assistants to the President at 18 Months: White House Turnover Among the Highest Ranking Staff and Positions" (PDF). whitehousetransitionproject.org. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/01/20/president-joe-biden-announces-acting-federal-agency-leadership/

- https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/01/20/president-joe-biden-announces-acting-federal-agency-leadership/

- https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/01/20/president-joe-biden-announces-acting-federal-agency-leadership/

- Chen, James; Beers, Brian. "Utilizing Checks and Balances to Reduce Mistakes and Bad Behavior". Investopedia.

- Waxman, Matthew C. (August 30, 2011). National Security Federalism in the Age of Terror. Stanford Law Review, , Vol. 64, 2012; Columbia Public Law Research Paper. p. 11–271. SSRN 1830312.

- Kirschner, Glenn. "Opinion | Trump claims that impeachment is a "coup." And he's (almost) right". NBC News.

- "Appropriations Committee Releases Fiscal Year 2016 Financial Services Bill". House Appropriations Committee. May 24, 2016. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- "Appropriations Committee Releases Fiscal Year 2015 Financial Services Bill". House Appropriations Committee. July 16, 2014. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- "Appropriations Committee Releases Fiscal Year 2014 Financial Services Bill". House Appropriations Committee. July 17, 2013. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- "Appropriations Committee Releases Fiscal Year 2013 Financial Services Bill". House Appropriations Committee. June 5, 2012. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- "Appropriations Committee Releases Fiscal Year 2012 Financial Services Bill". House Appropriations Committee. June 15, 2011. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- "Financial Services and General Government (FSGG): FY2011 Appropriations". Congressional Research Service. July 11, 2011. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- "Financial Services and General Government (FSGG): FY2010 Appropriations" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. February 4, 2010. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- "Financial Services and General Government (FSGG): FY2009 Appropriations" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. May 12, 2009. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- "Financial Services and General Government (FSGG): FY2008 Appropriations". Congressional Research Service. December 20, 2007. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- "Historical Tables, Table 4.1—OUTLAYS BY AGENCY: 1962–2022". Office of Management and Budget. January 20, 2017. Retrieved June 30, 2019.

External links

- Executive Office of the President Archived August 2, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- The Debate Over Selected Presidential Assistants and Advisors: Appointment, Accountability, and Congressional Oversight Congressional Research Service

- Proposed and finalized federal regulations from the Executive Office of the President of the United States

- Works by Executive Office of the President of the United States at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Executive Office of the President of the United States at Internet Archive