Australian Army

The Australian Army is the military land force of Australia. Formed in 1901, as the Commonwealth Military Forces, through the amalgamation of the Australian colonial forces following federation; it is part of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) along with the Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Australian Air Force. While the Chief of the Defence Force (CDF) commands the ADF, the Army is commanded by the Chief of Army (CA). The CA is therefore subordinate to the CDF but is also directly responsible to the Minister for Defence.[2] Although Australian soldiers have been involved in a number of minor and major conflicts throughout Australia's history, only during the Second World War has Australian territory come under direct attack.

| Australian Army | |

|---|---|

| |

| Founded | 1 March 1901 |

| Country | Australia |

| Type | Army |

| Size | 29,511 (Regular) 18,738 (Active Reserve)[1] |

| Part of | Australian Defence Force |

| Engagements | |

| Website | www |

| Commanders | |

| Commander-in-chief | General David Hurley (As Governor-General of Australia) |

| Chief of the Defence Force | General Angus Campbell |

| Chief of Army | Lieutenant General Rick Burr |

| Deputy Chief of Army | Major General Anthony Rawlins |

| Commander Forces Command | Major General Chris Field |

| Insignia | |

| Australian Army flag | .svg.png.webp) |

| Roundel (aviation) |  |

| Roundel (armoured vehicles) |  |

The history of the Australian Army can be divided into two periods, the 1901–47 period, when limits were set on the size of the regular Army, the vast majority of peacetime soldiers were in reserve units of the Citizens Military Force (also known as the CMF or Militia), and expeditionary forces (the First and Second Australian Imperial Forces) were formed to serve overseas.[3][4] The second period, which was post-1947, when a standing peacetime regular infantry force was formed and the CMF (known as the Army Reserve after 1980) began to decline in importance.[5][4]

During its history the Australian Army has fought in a number of major wars, including: Second Boer War (1899–1902), First World War (1914–18), the Second World War (1939–45), Korean War (1950–53), Malayan Emergency (1950–60), Indonesia-Malaysia Confrontation (1962–66), Vietnam War (1962–73),[6] and more recently in Afghanistan (2001 – present) and Iraq (2003–09).[7] Since 1947 the Australian Army has also been involved in many peacekeeping operations, usually under the auspices of the United Nations, however the non-United Nations sponsored Multinational Force and Observers in the Sinai is a notable exception.

History

Formation

Formed in March 1901, with the amalgamation of the six separate colonial military forces, following the Federation of Australia, it consisted of the former New South Wales, Victorian, Queensland, Western Australian, South Australian and Tasmanian armed forces. During this period the Second Boer War was still in full force. The Defence Act of 1903, established the operation and command structure of the Australian Army.[8] In 1911, the Universal Service Scheme was introduced, meaning that conscription was introduced for males aged 14–26 into cadet and CMF units; though it did not prescribe or allow overseas service outside the states and territories of Australia. This restriction would be bypassed through the process of raising separate volunteer forces until the mid 20th century; this solution was not without its drawbacks, with it usually causing headaches in logistics.[9]

World War I

After the declaration of war on the Central Powers, the Australian Army raised the all volunteer First Australian Imperial Force (AIF) with an initial recruitment of 52,561 out of a promised 20,000 men. A smaller expeditionary force, the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (ANMEF) was created to deal with the German Pacific colonial holdings; with recruitment beginning on the 10 August 1914 and operations starting 10 days later.[10] The first actions of the war by Australian personnel occurred on the 11 September with the landing at Rabaul by ANMEF, and by the end of October 1914 Germany had no outposts in the Pacific.[11] During preparations to depart Australia by the AIF, the Ottoman Empire unleashed surprise attacks on Russian ships and joined the Central Powers; thereby receiving declarations war from the Allies between the period of 2–5 November 1914.[12]

After initial recruitment and training, the AIF departed for Egypt where they underwent further preparations, and during this period the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) was founded. Their deployment, training and reorganisation in Egypt were undertaken as preparations for the start of the invasion of the Ottoman Empire via the Gallipoli peninsula. The invasion began in early 1915, with the AIF landing on 25 April, in what is now known as ANZAC Cove. It quickly devolved into trench warfare, with the ANZACs having little success, and a stalemate ensued. After eight months of fighting, the evacuation of Gallipoli commenced on 15 December 1915 and finished on 20 December 1915, with no casualties recorded.[13] After some training in Egypt and further action against the Ottoman Empire, the AIF was primarily split between Light Horse and infantry units and further expanded. The later would go to the western front whereas the mounted units would stay in the Middle East to fight the Ottomans in Arabia.[14]

The AIF arrived in France with the 1st, 2nd, 4th and 5th Divisions; which comprised, in part, I ANZAC Corps and, in full, II ANZAC Corps. The 3rd Division would not arrive until November 1916 from England where it had been training since its transfer from Australia. The infantry units commenced operations on the Western Front with the Battle of the Somme, and more specifically at Fromelles in July 1916. Soon after, the 1st, 2nd and 4th Divisions became tied down in the actions at Pozières and Mouquet Farm. In total, the operations cost the AIF 28,000 in casualties in around six weeks.[15] Due to these losses and pressure from the British War Council to maintain the required, and agreed upon, levels of manpower, Prime Minister Billy Hughes introduced the first conscription plebiscite on 28 October 1916. It was defeated by a narrow margin and created a bitter divide on the issue of conscription throughout the 20th century.[16][17] Following the withdrawal of the Germans to the Hindenburg Line trench system, which was better defended and eased manpower problems by reducing the frontline, in March 1917, and the subsequent pursuit by Australian divisions, the first Australian assault on the line occurred on 11 April 1917 with the First Battle of Bullecourt.[18][19][20]

The Australian mounted units, composed of the ANZAC Mounted Division and eventually the Australian Mounted Division, participated in the Middle Eastern Campaign. They were originally stationed there to protect the Suez Canal from the Turks, and following the threat of its capture passing, they started offensive operations and helped in the re-conquest of the Sinai Desert. This was followed by the Battles of Gaza, wherein on the 31 October 1917 the 4th and 12th Light Horse took Beersheba through the last charge of the Light Horse. They continued on to capture Jerusalem on 10 December 1917 and then eventually Damascus on 1 October 1918 whereby, a few days later on 10 October 1918, the Ottoman Empire surrendered.[11][14]

Interwar years

Repatriation efforts were implemented following the war and finished by the end of 1919.[21] In 1921, a decision was made to renumber the Citizens Military Forces units to that of the AIF.[22] During this period there was complacency towards matters of defence due to the effects of the previous war.[23] Following the election of Prime Minister James Scullin in 1929, conscription was abolished and the Great Depression hit, this led to a decrease in defence expenditure and manpower for the army.[24] To also reflect the new volunteer nature of the Citizen Forces, they were renamed to the Militia.[25]

World War II

Following the declaration of war on Germany and her allies by Britain, and the subsequent confirmation by Prime Minister Robert E. Menzies on 3 September 1939,[26] the Australian Army raised the Second Australian Imperial Force, a 20,000-strong volunteer expeditionary force, which initially consisted of the 6th Division; later increased to include the 7th and 9th Divisions, alongside the 8th Division which was sent to Singapore.[27][14] As part of efforts to ready Australia, compulsory military training recommenced in October 1939 for unmarried males aged 21, who had to complete a period of three months of training.[17]

The initial force commenced its first operations in North Africa, and the war, with the Operation Compass offensive; beginning with the Battle of Bardia.[14][28] This was followed by the supply of Australian units to Greece to defend against an invasion by Axis forces, which ultimately failed and a fighting withdrawal was issued.[29] Australian troops landed in Crete after the evacuation of Greece to defend against an airborne invasion, which was more successful but still failed and another withdrawal was ordered.[30] During this period the Allies were pushed back to Egypt and Tobruk came under siege by the Germans, with the primary defence personnel being Australians of the 9th Division; they lasted for 241 days before Tobruk was freed, however the Australians were relieved earlier than this.[31] Also, in June and July 1941, the AIF participated in the invasion of Syria, a Vichy French mandate, in response to German air forces being stationed there.[14] The 9th Division fought in actions in El Alamein before also being shipped home to fight the Japanese.[32]

.jpg.webp)

Following the entrance and announcement of war by Japan in December 1941, alongside its subsequent victories that conquered most of South East Asia by the end of March 1942, the militia was mobilised and the AIF was requested to return to Australia. This haste was increased when Singapore fell, in which the 8th Division was captured, and was the impetus for the relief of Australian troops at Tobruk, with the 6th and 7th Divisions immediately being sent to Australia to reinforce the defensive positions of New Guinea.[26] General conscription was also reintroduced, with service again being limited to Australia's territorial possessions, namely New Guinea. There were continued tensions between personnel of the AIF and Militia due to the latter's perceived inferior fighting ability which led to their nickname of "chocos", short for chocolate soldiers; this was in the belief that they would melt in the heat of combat.[17][33][34]

The naval engagement of the Imperial Japanese Navy by the Royal Australian Navy and US Navy in the Battle of the Coral Sea, and subsequent denial of the Japanese achieving their objective, was the impetus for the overland invasion to capture Port Moresby via the Owen Stanley mountain range.[35] This invasion, which occurred on 21 July 1942 when the Japanese landed at Gona, alongside Australian defensive actions, represented the Kokoda campaign. Australian forces tried to slow the advancing Japanese with operations across the Kokoda track and eventually succeeded, with the resultant operations concluded with the Japanese being driven out of New Guinea entirely.[36] In parallel with the Kokoda campaign being waged, another landing took place at Milne Bay on 25 August 1942 with fighting lasting until 7 September 1942 when the Japanese were repulsed; this is widely considered to be the first significant reversal of the Japanese forces for the war.[37] The Kokoda Track Campaign ended after the Japanese withdrawal in November 1942, with subsequent advances leading to the Battle of Buna–Gona on 16 November 1942; this battle continued until 2 January 1943.[36][38] In early 1943, the Australian Army started offensive actions to recapture Lae and Salamaua, where the Japanese had been entrenched since 8 March 1942.[39]

Cold War

After the surrender of Japan, the Australian provided a contingent to the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF), with mainly volunteers from the 2nd AIF. The units that comprised the brigade would eventually become the nucleus of the regular army, with the battalions and brigade being renumbered to reflect this change. Following the start of the Korean War, the Australian Army committed troops to fight against the North Korean forces; the units came from the Australian contribution to BCOF. The 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (3RAR) arrived in Pusan on 28 September 1950. Australian troop numbers would increase and continue to be deployed up until the armistice, with 3RAR being eventually joined by the 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (1RAR).[40][41]

The Australian Army committed the 2nd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (2RAR) in the Malayan Emergency, a guerrilla conflict between communist forces and Malay allies over ethnic Chinese citizenship, in October 1955. The operations consisted of primarily patrolling actions and guarding infrastructure; they rarely saw combat and by the time of their deployment, the confrontation was in its final stage. 2RAR rotated out with 3RAR and consequently 1RAR, with 2RAR completing another tour before the end of Australian Operations. The end of deployments of Australian troops occurred in August 1963, 3 years after the official ending of the emergency.[42] The Indonesian (or Borneo) Confrontation was the result of Indonesia's opposition to the formation of Malaysia, with Australian support in the conflict beginning and extending primarily with the training and supply of Malaysian troops. The initial combat unit deployed was 3RAR, with the deployment of 4th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (4RAR) following after.[43][44]

Vietnam War

The Australian Army commenced its involvement in the Vietnam War by sending military advisors in 1962. This was then increased by bringing in combat troops, the 1RAR, on 27 May 1965. In March 1966, the Australian Army increased this force again with the replacement of 1RAR with the 1st Australian Task Force; a force in which all nine battalions of the Royal Australian Regiment would serve. One of heaviest actions occurred in August 1966, the Battle of Long Tan, wherein D Company, 6th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (6RAR) successfully fended off an enemy force, estimated at 2,000 men, for four hours. Australian forces, in 1968, defended against the Tet Offensive and repulsed them with few casualties. The contribution of personnel to the war was gradually wound down, which started in late 1970 and ended in 1972; while the official declaration of the end of Australia's involvement in the war happened on 11 January 1973.[45][46]

Following the invasion of Kuwait by Iraq in August 1990, a coalition of countries sponsored by the UN Security Council, of which Australia was a part, gave a deadline for Iraq to withdraw from Kuwait of the 15 January 1991. Iraq refused to retreat and thus full conflict and the Gulf War began two days later on 17 January 1991.[47] In January 1993, the Australian Army deployed 26 personnel on an ongoing rotational basis to the Multinational Force and Observers (MFO), as part of non United Nations peacekeeping organisation that observes and enforces the peace treaty between Israel and Egypt.[48]

Recent history (1999–present)

Australia's largest peacekeeping deployment began in 1999 in East Timor, while other ongoing operations include peacekeeping in the Sinai (as part of MFO), and the United Nations Truce Supervision Organization. Humanitarian relief after the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake in Aceh Province, Indonesia, Operation Sumatra Assist, ended on 24 March 2005.[49]

Following the 11 September 2001 terrorist attack on the World Trade Centre, Australia promised troops to any military operations that the US commenced in response to the attacks. Subsequently, the Australian Army committed combat troops to Afghanistan in Operation Slipper. This combat role continued until the end of 2013 when it was replaced by a training contingent operating under Operation Highroad.[50][51]

After the Gulf War the UN imposed heavy restrictions on Iraq to stop them producing weapons of mass destruction. The US accused Iraq of possessing these weapons and presented evidence of this from unsubstantiated reports and requested that the UN invade the country to seize them, a motion which Australian supported. This was denied, however, the this did not stop a coalition led by the US, and joined by Australia, invading the country; thus starting the Iraq War on 19 March 2003.[52]

Between April 2015 and June 2020, the Army deployed a 300-strong element to Iraq, designated as Task Group Taji, as part of Operation Okra. In support of a capacity building mission, Task Group Taji's main role was to provide training to Iraqi forces, during which Australian troops have served alongside counterparts from New Zealand.[53][54]

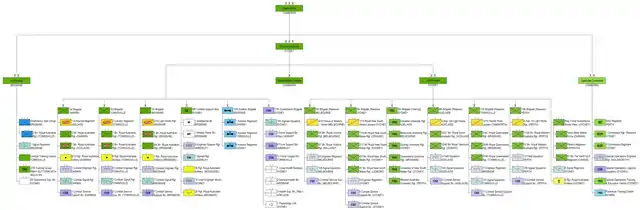

Current organisation

The 1st Division comprises a deployable headquarters, while 2nd Division under the command of Forces Command is the main home-defence formation, containing Army Reserve units. The 2nd Division's headquarters only performs administrative functions. The Australian Army has not deployed a divisional-sized formation since 1945 and does not expect to do so in the future.[55]

1st Division

1st Division carries out high-level training activities and deploys to command large-scale ground operations. It has few combat units permanently assigned to it, although it does currently command the 2nd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment as part of Australia's amphibious task group.[56]

Forces Command

Forces Command controls for administrative purposes all non-special-forces assets of the Australian Army. It is neither an operational nor a deployable command. Forces Command comprises:[57]

- 1 Brigade – Multi-role Combat Brigade based in Darwin and Adelaide.

- 3 Brigade – Multi-role Combat Brigade based in Townsville.

- 6 Brigade (CS&ISTAR) – Mixed brigade based in Sydney.

- 7 Brigade – Multi-role Combat Brigade based in Brisbane.

- 16 Aviation Brigade – Army Aviation brigade based in Enoggera, Brisbane.

- 17 Sustainment Brigade – Logistic brigade based in Sydney.

- 2nd Division administers the reserve forces from its headquarters located in Sydney.

- 4 Brigade – based in Victoria.

- 5 Brigade – based in New South Wales.

- 8 Brigade – training brigade with units around Australia

- 9 Brigade – based in South Australia and Tasmania.

- 11 Brigade – based in Queensland.

- 13 Brigade – based in Western Australia.

Additionally, Forces Command includes the following training establishments:

- Army Recruit Training Centre at Kapooka, NSW;

- Royal Military College, Duntroon in the ACT;

- Combined Arms Training Centre at Puckapunyal, Vic;

- Army Logistic Training Centre at Bonegilla, Vic and Bandiana, Vic; and

- Army Aviation Training Centre at Oakey, QLD.[58]

Special Forces

Special Operations Command comprises a command formation of equal status to the other commands in the ADF. It includes all of Army's special forces assets.[59][60]

Colours, standards and guidons

Infantry, and some other combat units of the Australian Army carry flags called the Queen's Colour and the Regimental Colour, known as "the Colours".[61] Armoured units carry Standards and Guidons – flags smaller than Colours and traditionally carried by Cavalry, Lancer, Light Horse and Mounted Infantry units. The 1st Armoured Regiment is the only unit in the Australian Army to carry a Standard, in the tradition of heavy armoured units. Artillery units' guns are considered to be their Colours, and on parade are provided with the same respect.[62] Non-combat units (combat service support corps) do not have Colours, as Colours are battle flags and so are only available to combat units. As a substitute, many have Standards or Banners.[63] Units awarded battle honours have them emblazoned on their Colours, Standards and Guidons. They are a link to the unit's past and a memorial to the fallen. Artillery do not have Battle Honours – their single Honour is "Ubique" which means "Everywhere" – although they can receive Honour Titles.[64]

The Army is the guardian of the National Flag and as such, unlike the Royal Australian Air Force, does not have a flag or Colours. The Army, instead, has a banner, known as the Army Banner. To commemorate the centenary of the Army, the Governor General Sir William Deane, presented the Army with a new Banner at a parade in front of the Australian War Memorial on 10 March 2001. The Banner was presented to the Regimental Sergeant Major of the Army (RSM-A), Warrant Officer Peter Rosemond.

The Army Banner bears the Australian Coat of Arms on the obverse, with the dates "1901–2001" in gold in the upper hoist. The reverse bears the "rising sun" badge of the Australian Army, flanked by seven campaign honours on small gold-edged scrolls: South Africa, World War I, World War II, Korea, Malaya-Borneo, South Vietnam, and Peacekeeping. The banner is trimmed with gold fringe, has gold and crimson cords and tassels, and is mounted on a pike with the usual British royal crest finial.[65]

Personnel

Strength

As of June 2018 the Army had a strength of 47,338 personnel: 29,994 permanent (regular) and 17,346 active reservists (part-time).[66] In addition, the Standby Reserve has another 12,496 members (as of 2009).[67] As of 2018, women make up 14.3% of the Army – well on track to reach its current goal of 15% by 2023. The number of women in the Australian military has increased dramatically since 2011 (10%), with the announcement that women would be allowed to serve in frontline combat roles by 2016.[68]

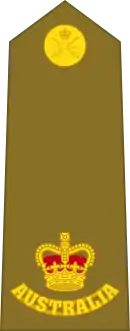

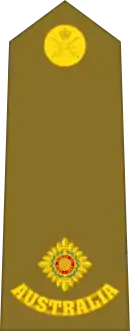

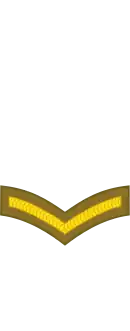

Rank and insignia

The ranks of the Australian Army are based on the ranks of the British Army, and carry mostly the same actual insignia. For officers the ranks are identical except for the shoulder title "Australia". The Non-Commissioned Officer insignia are the same up until Warrant Officer, where they are stylised for Australia (for example, using the Australian, rather than the British coat of arms).[69] The ranks of the Australian Army are as follows:

| NATO Code | OF-10 | OF-9 | OF-8 | OF-7 | OF-6 | OF-5 | OF-4 | OF-3 | OF-2 | OF-1 | OF(D) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

_(OCDT).svg.png.webp) |

_(SCDT).svg.png.webp) | |

| Rank title: | Field Marshal | General | Lieutenant General | Major General | Brigadier | Colonel | Lieutenant Colonel | Major | Captain | Lieutenant | Second Lieutenant | Officer Cadet | Staff Cadet |

| Abbreviation: | FM | Gen | Lt Gen | Maj Gen | Brig | Col | Lt Col | Maj | Capt | Lt | 2Lt | OCDT | SCDT |

| NATO Code | OR-9 | OR-8 | OR-7 | OR-6 | OR-5 | OR-4 | OR-3 | OR-2 | OR-1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No insignia | |||

| Rank Title: | Regimental Sergeant Major of the Army | Warrant Officer class 1 | Warrant Officer class 2 | Staff Sergeant (Phased out as of 2019) | Sergeant | Corporal | Lance Corporal | Private

(or equivalent) |

Recruit | |

| Abbreviation: | RSM-A | WO1 | WO2 | SSgt | Sgt | Cpl | LCpl | Pte | Rec | |

Uniforms

The Australian Army uniforms are grouped into nine categories, with additional variants of the uniform having alphabetical suffixes in descending order, which each ranges from ceremonial dress to general service and battle dress. The Slouch hat is the regular service and general duties hat, while the field hat is for use near combat scenarios.[70] The summarised categories are as follows:

- No 1 – Ceremonial Service Dress

- No 2 – Ceremonial Parade Dress/General Duty Dress

- No 3 – Ceremonial Safari Suit

- No 4 – Multicam Dress

- No 5 – Crewman Dress

- No 6 – Mess Dress

- No 7 – Working Dress

- No 8 – Maternity Dress

- No 9 – Aircrew Dress

Equipment

Firearms and artillery

| Small arms | F88 Austeyr (service rifle), F89 Minimi (support weapon), Browning Hi-Power (sidearm), MAG-58 (general purpose machine gun), SR-25 designated marksman rifle, SR-98 (sniper rifle), Mk48 Maximi, AW50F |

| Special forces | M4 carbine, Heckler & Koch USP, SR-25, F89 Minimi, MP5, SR-98, Mk48, HK416, HK417, Blaser R93 Tactical, Barrett M82, Mk14 EBR |

| Artillery | 54 M777A2 155 mm Howitzer, F2 81 mm Mortar.[71][72] |

Vehicles

| Main battle tanks | 59 M1A1 Abrams |

| Armoured recovery vehicle | 13 M88A2 Hercules armoured recovery vehicles[73][74] |

| Reconnaissance vehicles | 257 ASLAV. To be replaced, beginning in 2019, with 211 Boxer (armoured fighting vehicle) |

| Armoured Personnel Carriers | 431 M113 Armoured Vehicles upgraded to M113AS3/4 standard (around 100 of these will be placed in reserve) |

| Infantry Mobility Vehicles | 1,052 Bushmaster PMVs;[75][76][77] 31 HMT Extenda Mk1 Nary vehicles and 89 HMT Extenda Mk2 on order |

| Light Utility Vehicles | 2,268 G-Wagon 4 × 4 and 6x6, 1,500 Land Rover FFR and GS, 1,295 Unimog 1700L |

Support

| Radar | AN/TPQ-36 Firefinder radar, AMSTAR Ground Surveillance RADAR, AN/TPQ-48 Lightweight Counter Mortar Radar, GIRAFFE FOC, Portable Search and Target Acquisition Radar – Extended Range. |

| Unmanned Aerial Vehicles | RQ-7B Shadow 200, Wasp AE, and PD-100 Black Hornet[78][79] |

Aircraft

| Aircraft | Type | Versions | Number in service[80] | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Helicopters | ||||||

| Boeing CH-47 Chinook | Transport helicopter |

CH-47F |

10[81] |

One CH-47D lost in Afghanistan on 30 May 2011. From an initial fleet of six; two additional CH-47Ds were ordered in December 2011 as attrition replacement and to boost heavy lift capabilities until the delivery of seven CH-47Fs, which will replace the CH-47Ds. All seven Chinooks were delivered in August 2015. The US State Department has approved the possible sale of three more CH-47F aircraft as of December 2015.[82] The 2016 Defence White Paper confirmed the order of three CH-47F aircraft.[83] | ||

| Eurocopter EC135 | Training helicopter | EC135T2+ | 15 | Delivery completed 22 November 2016 [84][85] | ||

| Eurocopter Tiger | Attack helicopter | Tiger ARH | 22 | Delivery completed early July 2011. Achieved Final Operational Capability on 14 April 2016.[86] To be replaced by AH-64E Apache.[87] | ||

| AH-64 Apache | Attack helicopter | AH-64Ev6 Apache Guardian | 0 (29) | To replace Eurocopter Tiger.[87] | ||

| UH-60 Black Hawk | Utility helicopter | S-70A-9 | 20 | Replaced by the MRH 90 in 2017 for utility and transport roles. 20 to be kept in operational service for special forces until the end of 2021 due to issues with MRH 90.[88][89] | ||

| NHIndustries MRH-90 Taipan | Utility helicopter | TTH: Tactical Transport Helicopter | 47 | 47 in service (including 6 for Royal Australian Navy) | ||

Australian Army Sikorsky S-70 Black Hawk

Australian Army Sikorsky S-70 Black Hawk_NHI_MRH-90_arriving_at_Wagga_Wagga_Airport.jpg.webp) An Australian Army MRH-90

An Australian Army MRH-90_Eurocopter_Tiger_ARH_display_at_the_2015_Australian_International_Airshow.jpg.webp) Australian Army Tiger ARH

Australian Army Tiger ARH

Bases

The Army's operational headquarters, Forces Command, is located at Victoria Barracks in Sydney.[90] The Australian Army's three regular brigades are based at Robertson Barracks near Darwin,[91] Lavarack Barracks in Townsville, and Gallipoli Barracks in Brisbane.[92] The Deployable Joint Force Headquarters is also located at Gallipoli Barracks.[93]

Other important Army bases include the Army Aviation Centre near Oakey, Queensland, Holsworthy Barracks near Sydney, Lone Pine Barracks in Singleton, New South Wales and Woodside Barracks near Adelaide, South Australia.[94] The SASR is based at Campbell Barracks Swanbourne, a suburb of Perth, Western Australia.[95]

Puckapunyal, north of Melbourne, houses the Australian Army's Combined Arms Training Centre,[96] Land Warfare Development Centre, and three of the five principal Combat Arms schools. Further barracks include Steele Barracks in Sydney, Keswick Barracks in Adelaide, and Irwin Barracks at Karrakatta in Perth. Dozens of Australian Army Reserve depots are located across Australia.[97]

Australian Army Journal

Since June 1948, the Australian Army has published its own journal titled the Australian Army Journal. The journal's first editor was Colonel Eustace Keogh, and initially, it was intended to assume the role that the Army Training Memoranda had filled during the Second World War, although its focus, purpose, and format has shifted over time.[98] Covering a broad range of topics including essays, book reviews and editorials, with submissions from serving members as well as professional authors, the journal's stated goal is to provide "...the primary forum for Army's professional discourse... [and to facilitate]... debate within the Australian Army ...[and raise] ...the quality and intellectual rigor of that debate by adhering to a strict and demanding standard of quality".[99] In 1976, the journal was placed on hiatus as the Defence Force Journal began publication;[98] however, publishing of the Australian Army Journal began again in 1999 and since then the journal has been published largely on a quarterly basis, with only minimal interruptions.[100]

See also

Citations

- Commonwealth of Australia (2019). "Department of Defence Annual Report 2018-19" (PDF). Department of Defence.

- "Defence Act (1903) – SECT 9 Command of Defence Force and arms of Defence Force". Australasian Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- Grey 2008, pp. 88 & 147.

- Odgers 1988, p. 5.

- Grey 2008, pp. 200–201.

- Odgers 1988.

- Grey 2008, pp. 284–285.

- "Defence Act 1903". Federal Register of Legislation. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- "Universal Service Scheme, 1911–1929". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- "Australian Naval & Military Expeditionary Force (ANMEF)". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- "First World War 1914–18". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- "Ottoman Empire enters the First World War". New Zealand History. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- "Evacuation from Gallipoli 1915". Australian Government: Department of Veteran's Affairs. 6 November 2020.

- Moore, Jonathan J. (2018). A History of the Australian Military: From the First Fleet to the Modern Day. New Holland Publishers. ISBN 9781760790479.

- "WWI The Western Front". Australian Army. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- "Conscription referendum". National Museum Australia. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- Frame, Tom. "Conscription, Conscience and Parliament". Parliament of Australia. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- "Attack on Noreuil". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- Tibbitts, Craig (3 April 2007). "The Battles for Bullecourt". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- "Hindenburg Line". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- Payton, Philip (2018). Repat: A Concise History of Repatriation in Australia (PDF). Department of Veterans' Affairs. ISBN 978-0-9876151-8-3. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- Grey 2008, p. 125.

- "Chapter 1 – The Inter-War Period, 1919–1939". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- Stockings, Craig (2007). The Torch and the Sword: A History of the Army Cadet Movement in Australia. UNSW Press. p. 86. ISBN 9780868408385.

- Palazzo 2001, p. 110.

- "Australia and the Second World War". Department of Veteran's Affairs. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- Long, Gavin (1961). "Volume I – To Benghazi (1961 reprint)". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- "Battle of Bardia". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- "Greek Campaign". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- "Crete Campaign". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- "Battles for Tobruk". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- "Second World War, 1939–45". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- "The offending 'M' – WW2 Army service numbers". Australian Army. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- "Second World War conscription". National Museum of Australia. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- "Battle of the Coral Sea". Royal Australian Navy. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- "Kokoda Trail Campaign". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- Anderson, Nicholas. "Milne Bay - Papua New Guinea". Australian Army. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- "Battle of Buna". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- Stanley, Peter. "New Guinea Offensive". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- "Out in the Cold: Australia's involvement in the Korean War". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- "Korean War, 1950–1953". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- "Malayan Emergency". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- "Indonesian Confrontation". National Museum of Australia. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- "Indonesian Confrontation, 1963–66". Australian War Memorial.

- "Vietnam War 1962–75". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- "Australian troops committed to Vietnam". National Museum Australia. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- "The Gulf War 1990–91". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- "MFO - Contingents". Multinational Force Observers. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- "Australian War Memorial Official History of Peacekeeping, Humanitarian and Post-Cold War Operations". Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- "Afghanistan, 2001–present". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- "Official Histories – Iraq, Afghanistan and East Timor". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- "Australians in Iraq 2003 – War in Iraq". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- Department of Defence (15 April 2015). "Troops to deploy to Iraq" (Press release). Archived from the original on 3 April 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- Brennan, Roger (5 June 2020). "Task Group Taji operation a success". Department of Defence. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- Horner 2001, p. 195.

- Doran, Mark. "Amphibious Display". Army. Department of Defence. p. 12.

- "Organisation structure". Army. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- "Forces Command". Australian Army. Archived from the original on 7 September 2013. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- "Special Operations Command Booklet". Australian Army. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- Senator Robert Hill, Minister for Defence (5 May 2003). "New Special Operations Command" (Press release). Department of Defence. Archived from the original on 2 June 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- Jobson 2009, p. 53.

- Jobson 2009, pp. 55–56.

- "National Flags, Military Flags, & Queens and Regimental Colours". Digger History. Archived from the original on 5 April 2007. Retrieved 3 April 2007.

- Jobson 2009, p. 58.

- "Army Flags (Australia)". Flags of the World. Archived from the original on 3 April 2007. Retrieved 3 April 2007.

- Commonwealth of Australia (2019). "Department of Defence Annual Report 2017-18" (PDF). Department of Defence. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- Australian National Audit Office (2009). Army Reserve Forces (PDF). Audit Report No. 31 2008–09. Canberra: Australian National Audit Office. ISBN 0-642-81063-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 May 2009.

- Commonwealth of Australia (2019). "Women in the ADF Report 2017-18: A Supplement To The Defence Annual Report 201718". Department of Defence. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- Jobson 2009, pp. 8–17.

- "Army Dress Manual". Army. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- "81 millimetre F2 Mortar". Australian Army. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- "M777 155mm lightweight towed howitzer". Australian Army. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- Australian Army. "M1 Abrams Tank – Australian Army". www.army.gov.au. Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- "Army officially accepts new armoured vehicles". defenceconnect.com.au. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- "Contract Signed for Additional Bushmasters" (Press release). The Hon. Joel Fitzgibbon MP, Minister for Defence. 29 October 2008. Retrieved 29 October 2008.

- "More vehicles on the way". Army News. Canberra: Australian Department of Defence. 26 May 2011. p. 16.

- "Australian Army orders additional Bushmasters from Thales". Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- "Unmanned Aerial Vehicles | Army.gov.au". www.army.gov.au. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- "Australian Army tests out drones for surveillance". iTnews. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- "World Air Forces 2016 report". flightglobal.com. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- "Three more CH-47F helicopters delivered ahead of schedule in FMS deal". Australian Aviation. 26 June 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- "Australia set to acquire three more CH-47F Chinooks". Australian Aviation. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- 2016 Defence White Paper (PDF). Australia: Commonwealth of Australia. 2016. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-9941680-5-4.

- "Minister for Defence – New training system for ADF helicopter crews". Media Release. Minister for Defence. 23 October 2014. Archived from the original on 25 August 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- McMaugh, Dallas (9 April 2016). "Future ADF training helicopter arrives at HMAS Albatross". Royal Australian Navy. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- Beurich, Cpl Sebastian (28 July 2016). "A story of innovation and commitment" (PDF). Army: The Soldiers' Newspaper (1378 ed). Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- McLaughlin, Andrew. "Apache confirmed as Tiger ARH replacement". ADBR. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- Kerr, Julian (2 December 2015). "Australian Army to extend Black Hawk service lives for special forces use". Jane 's Defence Weekly (53.4). Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- "S-70A-9 Black Hawk Weapons". Defence Materiel Organisation. Department of Defence. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- "Forces Command". Our people. Australian Army. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- "1st Brigade". Our people. Australian Army. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- "7th Brigade". Our people. Australian Army. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- "1st Division". Our people. Australian Army. Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- "Defence Bases". Department of Defence. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- Lee 2007, p. 30.

- "Australian Army skills at Arms Meet 2018". Media Releases. Department of Defence. 4 May 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- "About the Army: Locations". Defence Jobs. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- Dennis 1995, p. 60.

- "Australian Army Journal". Publications. Australian Army. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- "Past editions: Australian Army Journal". Publications. Australian Army. Archived from the original on 12 March 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

References

- Dennis, Peter; Grey, Jeffrey; Morris, Ewan; Prior, Robin (1995). The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-553227-9.

- Grey, Jeffrey (2008). A Military History of Australia (3rd ed.). Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-69791-0.

- Horner, David (2001). Making the Australian Defence Force. Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-554117-0.

- Jobson, Christopher (2009). Looking Forward, Looking Back: Customs and Traditions of the Australian Army. Wavell Heights, Queensland: Big Sky Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9803251-6-4.

- Lee, Sandra (2007). 18 Hours: The True Story of an SAS War Hero. Pymble, New South Wales: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-73228-246-2.

- Odgers, George (1988). Army Australia: An Illustrated History. Frenchs Forest, New South Wales: Child & Associates. ISBN 0-86777-061-9.

- Palazzo, Albert (2001). The Australian Army: A History of its Organisation 1901–2001. Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-551506-0.

Further reading

- Australian Department of Defence (2009). Defence Annual Report 2008–09. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Defence Publishing Service. ISBN 978-0-642-29714-3.

- Grey, Jeffrey (2001). The Australian Army. South Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19554-114-4.

- Terrett, Leslie; Taubert, Stephen (2015). Preserving our Proud Heritage: The Customes and Traditions of the Australian Army. Newport, New South Wales: Big Sky Publishing. ISBN 9781925275544.