Baltimore City Hall

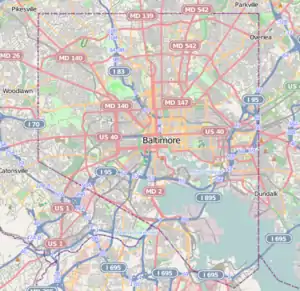

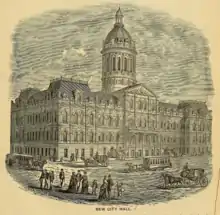

Baltimore City Hall is the official seat of government of the City of Baltimore, in the State of Maryland. The City Hall houses the offices of the Mayor and those of the City Council of Baltimore. The building also hosts the city Comptroller, some various city departments, agencies and boards/commissions along with the historic chambers of the Baltimore City Council. Situated on a city block bounded by East Lexington Street on the north, Guilford Avenue (formerly North Street) on the west, East Fayette Street on the south and North Holliday Street with City Hall Plaza and the War Memorial Plaza to the east, the six-story structure was designed by the then 22-year-old new architect, George Aloysius Frederick (1842–1924) in the Second Empire style, a Baroque revival, with prominent Mansard roofs with richly-framed dormers, and two floors of a repeating Serlian window motif over an urbanely rusticated basement.[2][3]

| Baltimore City Hall | |

|---|---|

Baltimore City Hall in April 2020 | |

| |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Second Empire style, a Baroque revival |

| Location | 100 North Holliday Street, (between East Lexington and Fayette Streets), facing City Hall Plaza/War Memorial Plaza. Baltimore, Maryland 21202 |

| Town or city | Baltimore, Maryland |

| Country | United States |

| Coordinates | 39.291°N 76.61073°W |

| Completed | 1867–1875 |

| Cost | $50,271,135.64 |

| Client | Mayor and City Council of Baltimore |

| Technical details | |

| Size | ~270 Feet |

Baltimore City Hall | |

| |

| Location | 100 N. Holliday St., Baltimore, Maryland |

| Area | less than one acre |

| Built | 1867 |

| Architect | Frederick, George A.; Bollman, Wendel |

| Architectural style | Renaissance, French Renaissance Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 73002180[1] |

| Added to NRHP | May 8, 1973 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | George Aloysuis Frederick, (1842–1924) |

History

The building's cornerstone was laid on the southeastern corner of the new municipal structure (on the northwestern corner of Fayette and Holliday Streets) in October, 1867 (with a famous historical photograph taken of the ceremony) audience stands and crowds from overhead on East Fayette Street with the east side of Holliday Street visible behind the stands showing the famed Holliday Street Theatre, where on November 12, 1814, the new poem by Francis Scott Key, (1779–1843), "The Defence of Fort McHenry" was first performed on the stage and next door (to the north), Prof. Knapp's School (attended by famed writer/author/editor H. L. Mencken in the 1880s) and the townhouses where the Loyola College and Loyola High School were founded in 1852, just to the left (south) next to the theatre was the vacant lot formerly housing the Theatre Tavern where the new song the Star-Spangled Banner was often sung to the merriment of all [later the CHS/BCC playground], and the edge of the old "Assembly-Rooms" social/concert/dance hall for the elite that later was home to the Central High School of Baltimore (later the Baltimore City College, 1843–1873), when the Theatre and School perished in a large famous fire. The massive new "pile" of a City Hall, acclaimed by many throughout the nation, was officially dedicated on October 25, 1875, $200,000 under-budget from its $2.5 million appropriation, amazingly and proudly in those "Robber Baron" Gilded Age times of the 19th Century.

The site for the "new" building was selected and some designs were submitted before the American Civil War. The cornerstone for the building, under Frederick's new design, was not laid until 1867; construction was completed eight years later. At a cost of more than $2 million (in 1870s money), the Baltimore City Hall is built largely of many courses and rows of thicknesses of brick with the exterior walls faced with white marble. The marble alone, quarried in Baltimore and Baltimore County (famous "Beaver Dam" quarry), cost $957,000.[4] The segmented dome capping the building is the work of Baltimore engineer Wendel Bollman, known for his iron railroad bridges. At the time of its construction, the cast iron roof was considered one of the largest structures of its kind.[5]

Renovations

By the end of World War II, City Hall was showing signs of age and deterioration. The slate roof leaked, the exterior marble was eroding in places and the heating, cooling and electrical systems needed to be replaced. Even the cast iron dome's fastenings had rusted through and many plates were cracked. In 1959, 15 pounds of iron ornament came loose and plunged 150 feet into the Board of Estimates hearing room. In 1974 the city voted to renovate the old city hall rather than build a new one. Architectural Heritage Inc., in association with Meyers, D'Aleo and Patton Inc., local architects, were retained to begin the design. The ceremonial chambers were restored and the office space was doubled. In the process the dome was disassembled and put back together. Two years and $10.5[6] million later the Mayor, the City Council and other city departments moved back into the building.[7] Usable space was increased almost twofold after the renovation, by fitting in two extra floors, by replacing dead storage space in the basement with offices, and by moving corridor walls to maximize office space.

In 2009, a building survey found that sections of the building's marble exterior were cracked and crumbling due to age. The city approved spending $483,000 for repairs to be made the same year.[8]

Incidents

On October 11, 1883, James F. Busey, a Democratic ward operative, was shot and killed outside of City Hall. The man who shot him, William T. Harig, was also a Democrat from another ward. The two got into a political argument and after some punches were thrown, both men drew their pistols and began firing at each other in rapid succession. Busey fired wildly; Harig did not, hitting Busey four times. Harig was taken into custody and charged with murder.[9]

Nearly 93 years later, Charles A. Hopkins stormed the temporary City Hall with a hand gun and killed a city councilman. On April 13, 1976, Hopkins, angered that his restaurant was being shut down, killed Dominic Leone, a member of the Baltimore City Council. Hopkins also wounded another city councilman, a police officer and a mayoral aide during the shooting spree. Hopkins was found not guilty by reason of insanity in the shootings but has spent most of his life since then at mental health facilities. In 2007, a Baltimore judge reduced his level of confinement.[10]

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "Baltimore City Hall". Johns Hopkins University. Archived from the original on 2008-04-14. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- Arthur Townsend (June 1972). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Baltimore City Hall" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

- City Hall: History of Construction and Dedication. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore. 1878.

- Dorsey, John; Dilts, James D. (1981). A Guide to Baltimore Architecture (Second ed.). Centreville, Maryland: Tidewater Publishers. pp. 86–87. ISBN 0-87033-272-4.

- "An Engineer's Guide To Baltimore". Johns Hopkins University. Archived from the original on September 2, 2006. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- Baltimore City Hall, Holliday Street, Baltimore, Independent City, MD. Historic American Buildings Survey. Library of Congress. c. 1981. Archived from the original on 2012-12-13. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- Linskey, Annie (May 21, 2009). "Things falling apart at Baltimore City Hall". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- "Baltimore Shooting Affray: Ward Politicians Engage In Target Practice". the New York Times. 1883-10-12. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- "Baltimore judge reduces level of confinement for City Hall shooter". The Daily Record. Baltimore. 2007-08-13. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

External links

Media related to Baltimore City Hall at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Baltimore City Hall at Wikimedia Commons- Baltimore City Hall, Baltimore City, including photo from 1971, at Maryland Historical Trust

- George A Frederick website

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. MD-46, "Baltimore City Hall, Holliday Street, Baltimore, Independent City, MD", 25 photos, 1 color transparency, 30 data pages, 3 photo caption pages