MARC Train

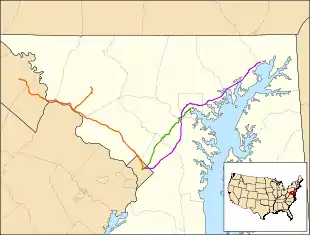

MARC (Maryland Area Regional Commuter) Train Service[3] (reporting mark MARC), previously known as Maryland Rail Commuter, is a commuter rail system comprising three lines in the Baltimore–Washington metropolitan area. MARC is administered by the Maryland Transit Administration (MTA), a Maryland Department of Transportation (MDOT) agency, and is operated under contract by Bombardier Transportation Services USA Corporation (BTS) and Amtrak over tracks owned by CSX Transportation (CSXT) and Amtrak.

| |||

.jpg.webp) | |||

| Overview | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Owner | Maryland Transit Administration | ||

| Locale | Baltimore–Washington metropolitan area | ||

| Transit type | Regional / commuter rail | ||

| Number of lines | 3 | ||

| Number of stations | 42 | ||

| Daily ridership | 40,100 (Q2 2016)[1] | ||

| Annual ridership | 9,149,900 (2015)[2] | ||

| Chief executive | Andrea Farmer | ||

| Website | MARC Train official page | ||

| Operation | |||

| Began operation | 1984 (as Maryland Rail Commuter) | ||

| Operator(s) | Bombardier Transportation (Camden and Brunswick Lines) Amtrak (Penn Line) (under contract to the Maryland Transit Administration) | ||

| Reporting marks | MARC | ||

| Host railroads | Amtrak CSX Transportation | ||

| Technical | |||

| System length | 187 mi (301 km) | ||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge | ||

| Electrification | 25Hz AC on the Penn Line | ||

| Top speed | 125 mph (201 km/h) | ||

| |||

MARC Train | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

With some equipment reaching speeds of 125 miles per hour (201 km/h) on the Penn Line, MARC is purported to be the fastest commuter railroad in the United States.[4]

Operations

MARC has three lines, all of which originate and terminate at Washington Union Station. It operates 94 trains on a typical weekday: the Brunswick Line (18 trains/19 trains on Fridays),[5] the Camden Line (21 trains),[6] and the Penn Line (58 trains).[7] The Penn Line is the only line that has weekend service, with 18 trains (comprising 9 round trips) on Saturdays, and 12 trains (comprising 6 round trips) on Sundays.[7] Service is suspended or reduced on select Federal holidays.

Like most commuter rail systems in North America, all MARC trains operate in push-pull mode, with the cab car typically leading trains traveling toward Washington. This configuration ensures that diesel locomotive fumes are kept further from the terminal at Union Station, and accommodates elevation gains by placing the locomotive at the head of trains heading outbound from Washington. Train lengths vary depending on the line and time of day; most trains are the typical three to five car consist, though some reach up to 10 cars on the Penn Line during rush hour. Shorter trains typically comprise either all Sumitomo/Nippon Sharyo single levels or all Kawasaki or Bombardier double levels (though the former two are in the process of being replaced by more Bombardiers) while longer trains often incorporate a mixture of each. Including back up locomotives is typical on many trains, as are "power moves" during rush hour meaning trains can incorporate one, two or even three locomotives at times.

Brunswick Line

The Brunswick Line is a 74 mi (119 km) line that runs on CSX-owned tracks between Washington, D.C., and Martinsburg, West Virginia, with a 14 mi (23 km) branch to Frederick, Maryland. It is descended from Baltimore & Ohio Railroad (B&O) commuter service between Washington and its northern and western suburbs.

Camden Line

The Camden Line is a 39 mi (63 km) line that runs on CSX-owned tracks between Washington, D.C., and Camden Station in Baltimore. It is descended from B&O commuter routes running between Washington and Baltimore. The B&O began operating over portions of this route in 1830, making it one of the oldest passenger rail lines in the U.S. still in operation.[8]

Penn Line

The Penn Line is a 77 mi (124 km) line that runs on Amtrak's Northeast Corridor tracks between Washington, D.C., and Perryville, Maryland, via Baltimore Penn Station. Most trains operate along a 39 mi (63 km) stretch between Washington and Baltimore, with limited service to Martin State Airport and Perryville. It is the fastest commuter rail line in North America, with equipment capable of operating at speeds up to 125 miles per hour (201 km/h).[4] Descended from Washington-Baltimore commuter routes operated by the Pennsylvania Railroad (hence the name), it is by far the busiest line, with almost twice as many trains and twice as many passengers as the other two lines combined. The Penn Line is the only line that operates on weekends.

Special Western Maryland service

Trains have made special weekend trips to and from Cumberland, Maryland. Past events have included trains for Western Maryland residents to attend sporting events in the Baltimore/Washington area, such as Baltimore Orioles or Washington Redskins games, or for Baltimore/Washington residents to attend Railfest in Cumberland and enjoy the scenic mountains and fall foliage of Western Maryland.[9]

Intermodal connections

Nearly all stations served by MARC connect with local bus or Metrobus service. Washington Union Station, New Carrollton, College Park, Greenbelt, Silver Spring and Rockville offer connections to the Metrorail subway; Baltimore Penn Station and Camden Station both offer connections to the Baltimore Light RailLink. Additionally, Washington Union Station and Baltimore Penn are the second- and eighth-busiest Amtrak stations in the country, respectively. BWI Airport, Aberdeen, New Carrollton, Rockville, Harpers Ferry and Martinsburg are shared with Amtrak as well. Washington Union Station also offers a connection to the VRE network into Northern Virginia.

History

Origins

All three MARC lines date from the 19th century. Service on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) between Baltimore and Ellicott City began on May 24, 1830; this route included part of what is now the Camden Line.[10] B&O service from Baltimore to Washington, the modern Camden Line route, began on August 25, 1835.[8]

The B&O's main line was extended to Frederick Junction (with a branch to Frederick) in 1831, to Point of Rocks in 1832, to Brunswick and Harpers Ferry in 1834, and Martinsburg in 1842. The B&O completed its Metropolitan Branch in 1873; most service from Martinsburg and Frederick was diverted onto the Metropolitan Branch to Washington and the old main line became a secondary route. This established the basic route for what would become the Brunswick Line.

The Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad (PW&B) completed its line between Baltimore and Philadelphia in December 1838, save for the ferry across the Susquehanna River, which was not bridged until the 1860s. Although the B&O was chartered with the unspoken assumption that no competing line would be built between Baltimore and Washington, the Pennsylvania Railroad-owned Baltimore and Potomac Railroad (B&P) was completed between the two cities in 1872.[11] The PW&B was initially hostile to the Pennsylvania (PRR); however, the PRR acquired it in a stock battle with the B&O in 1881. The PW&B soon began operating PRR through service – the ancestor of Penn Line service – between Washington and Philadelphia in conjunction with the B&P. Meanwhile, the PRR ended B&O trackage rights over the PW&B in 1884, forcing it to open its own parallel route in 1886. The PW&B and the B&P were combined into the PRR's Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington Railroad in 1902.[12]

The B&O ended local service on the Frederick Branch in November 1949. All B&O passenger service between Baltimore and Philadelphia ended in 1958; local service from Washington was curtailed to Camden Station. The B&O continued to offer local service to Brunswick plus long-distance service, while the PRR operated a mix of local, intercity, and long-distance service on the Northeast Corridor. Local service north of Baltimore on the PRR ended around 1964.

Public takeover

In the mid-20th century, passenger rail service declined owing to a variety of factors – particularly the advent of the automobile – even while commuting between suburban locations and urban business districts remained common. In 1968, the PRR folded into Penn Central, which took over its passenger operations.[13] On May 1, 1971, Amtrak took over most intercity passenger service in the United States, including some of Penn Central's former routes.[14] The B&O and Penn Central continued to operate their Washington–Baltimore and Washington–Brunswick commuter routes without subsidies.[15]

Amtrak initially operated (with federal subsidy) the Washington–Parkersburg West Virginian (later renamed Potomac Turbo then Potomac Special) The Potomac Special was cut back to a 146-mile (235 km) commuter-based Washington–Cumberland trip, the Blue Ridge, on May 7, 1973. In early 1974, the B&O threatened to discontinue its remaining unsubsidized commuter services, citing heavy losses. On March 1, 1974, the Maryland Department of Transportation (MDOT) began a 50% subsidy of the B&O's Washington–Brunswick and Washington–Baltimore service – the first state-sponsored commuter rail service to Washington.[16][17] In 1975, the state signed an operating agreement with the B&O, under which the state provided rolling stock and reimbursed the railroad for all operating losses.[17] On October 31, 1976, Amtrak introduced the Washington–Cincinnati Shenandoah and cut the Blue Ridge to a 73-mile (117 km) Washington–Martinsburg trip.[18] In the late 1970s, West Virginia began to fund the B&O shuttles between Brunswick and Martinsburg; the shuttles were soon incorporated as extensions of Brunswick service in order to secure Urban Mass Transportation Administration subsidies.[19] In December 1981, MDOT purchased 22 ex-PRR coaches for use on B&O lines.[20] The Maryland State Railroad Administration (SRA) was established in 1986 to administer contracts, procure rolling stock, and oversee short line railroads in the state.[17]

Conrail took over the unsubsidized ex-PRR Baltimore–Washington service from Penn Central at its creation on April 1, 1976.[21] MDOT began subsidizing that service after Conrail threatened to discontinue service on April 1, 1977.[22] Prior to 1978, most ex-PRR Baltimore–Washington service was operated by aging MP54 electric multiple units, most dating back to the line's 1933 electrification. In 1978, Amtrak and the City of Baltimore negotiated with the New Jersey Department of Transportation to lease a number of new Arrow railcars to replace the MP54s.[23] With funding from Pennsylvania and Maryland, Amtrak used some of the cars to initiate a Philadelphia–Washington commuter trip, the Chesapeake, on April 30, 1978.[23] The Chesapeake stopped at some local stations but fewer than the Conrail service; it provided commuter service from north of Baltimore for the first time since the 1960s.

BWI Rail Station opened for Amtrak and Conrail trains on October 26, 1980.[24] In August 1982, Conrail trains began stopping at Capital Beltway station, used by intercity trains since 1970. Lanham and Landover stations were closed.[25] Two additional round trips – one in the peak direction, and one reverse for commuters working in Baltimore – were added on July 5, 1983.[26] On October 30, 1983, Amtrak and MARC moved from Capital Beltway into a new platform and waiting room at nearby New Carrollton station, served by Metro since 1978.[27][28][29] The Edmondson Avenue and Frederick Road stops in Baltimore were replaced by West Baltimore station on April 30, 1984.[30]

In 1981, MDOT began installing highway signs to point drivers to commuter rail stations.[31] In 1982, law changes allowed Conrail to shed its commuter rail operations in order to focus on its more profitable freight operations. On January 1, 1983, public operators (including Metro-North Railroad, NJ Transit, and SEPTA Regional Rail) took over Conrail commuter rail systems in the Northeast. MDOT began paying Amtrak to run the ex-PRR Washington–Baltimore service.[17][20] That service was branded as AMDOT (Amtrak Maryland Department of Transportation).[32] In October 1983, with low patronage and largely duplicated by the MDOT-subsidized service, the Chesapeake was discontinued. In 1984, the SRA introduced a unified brand for its three subsidized lines, MARC (originally short for Maryland Rail Commuter, later modified to Maryland Area Rail Commuter). Operations remained the same, but public-facing elements like schedules and crew uniforms were consolidated under the new name.[17][20] MARC soon began calling its three lines the Penn Line, Camden Line, and Brunswick Line.

Improved service

In October 1986, MARC began testing an Amtrak AEM-7 locomotive, looking to use push-pull trains to replace the Arrows.[20] On February 27, 1989, MARC increased Washington–Baltimore service from 7 to 13 weekday round trips. A new park-and-ride station opened at Bowie State (site of Jericho Park station, closed in 1981) and Bowie station was closed.[20] Two more round trips were added in May 1989.[20]

On May 1, 1991, MARC service was extended north from Baltimore to Perryville with intermediate stops at Martin State Airport, Edgewood, and Aberdeen.[33] Between 1988 and 1993, MARC expanded service from 34 to 70 total daily trips across the system.[34] In 1995, 800 parking spaces were added to Odenton station.[35]

From 1989 to 1996, the Camden Line had high ridership growth and substantial changes to its stations. A new station at Savage just off Route 32 was opened on July 31, 1989.[36] MARC began service to Greenbelt station on May 3, 1993,[37] seven months before Metro began serving the station.[38] On January 31, 1994, MARC expanded midday service on the Camden and Brunswick lines, opened Laurel Race Track station to relieve a parking shortage at Laurel station, and closed the underused Berwyn station on the Camden Line.[39] On December 12, 1994, Muirkirk station (originally planned as South Laurel) was opened to reduce congestion on nearby Route 1.[40] In 1996, a $1.2 million project added 600 parking spaces at Savage station to relieve crowding.[35] In July 1996, the Elkridge station was closed and replaced with Dorsey station, which has a larger parking area and a dedicated interchange with Route 100.[41][42]

On April 30, 1987, the B&O was merged into CSX. CSX continued to operate Camden and Brunswick Line service.[20] On July 6, 1987, MARC opened Metropolitan Grove station – the first new station on the Brunswick line in over a century.[43][44]

Keolis controversy

Beginning as early as June 2010, MARC began looking for a new operator to replace CSX Transportation for the Camden and Brunswick Lines.[45]

Controversy first arose when the French-owned and Montgomery County, Maryland-based Keolis (already operating Virginia Railway Express trains) was the only bidder for the contract. The bidding process was suspended in the fall of 2010 due to lack of competition. Before bidding reopened in 2011, Maryland passed a law (at the request of Leo Bretholz and other Holocaust survivors) requiring Keolis's majority owner, French state railway company SNCF,[46] to fully disclose its role in transporting Jews to concentration camps during World War II (while SNCF was under control of the Nazi government). This disclosure would need to meet the satisfaction of the Maryland state archivist before Keolis would be allowed to place a bid for MARC service. Keolis faced similar issues while bidding for VRE operations in 2009, but was eventually given that contract.

Keolis and SNCF lawyers claimed that all documentation required by the law had been produced long before.[47] This was also asserted by Don Phillips in the July 2011 issue of Trains Magazine. Phillips states that a full 914-page independent report and complete history of SNCF's role in the Holocaust, released in 1996, is currently being translated into English.[48] Phillips cites from the publicly available English introduction to the report, noting that while some SNCF workers worked with the Nazis, acts of sabotage were frequent, and the Nazis shot 819 SNCF workers for refusing to carry out the rail orders of the government. An additional 1200 railway workers were themselves sent to concentration camps over SNCF rails. Phillips also notes that SNCF does business with the Israel rail system and works without government prompting to educate the current generation about the war and Holocaust.

In June 2011, the future of Keolis's ability to bid on the MARC contract remained up in the air with the new disclosure law in place. No other bidder had emerged to replace CSXT. On June 5, 2011, The Washington Post ran an editorial critical of the disclosure law. The Post claimed that SNCF has been working for years on digitizing its records, and the Maryland law may require items or formats counter to SNCF's current system and/or French law. The article also stated that some in the Maryland Attorney General's Office worried the law was not Constitutional, may risk retaliation towards Maryland firms overseas, and may risk federal funding for Maryland "by imposing arbitrary procurement demands on a single company."[49][50]

MTA issued a new Request for Proposals for the operations and maintenance of MARC services on the Brunswick and Camden Lines on July 14, 2011, with a deadline for proposals on November 21, 2011.[51] On October 17, 2012, a $204 million contract to run the Camden and Brunswick lines was awarded to the Canadian company Bombardier Transportation,[52] effectively ending the Keolis controversy. The pre-service transition period began on the Thursday of that week, during which time CSXT continued to operate MARC trains.[52][53]

Rolling stock

As of 2020, MARC operates with the following equipment:[54]

Current

| Image | Manufacturer | Model | Quantity | Unit Numbers | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

EMD | GP39H-2 | 6 | 70–75 | Entered service in the late 1980s. Used as a backup engine. |

.jpg.webp) |

Bombardier– Alstom | HHP-8 | 6 | 4910–4915 |

Only electric locomotives in fleet, first entered service in 1998. |

.jpg.webp) |

MPI | MP36PH-3C | 26 | 10–35 |

Replaced GP40WH-2s.[55] Entered service 2009–2011. |

|

Siemens | SC-44 | 8[56] | 80–87 | Delivered December 2017 – April 2018. They replaced AEM-7 locomotives.[57][58] |

Former

| Image | Manufacturer | Model | Quantity | Unit Numbers | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

EMD/ASEA | AEM-7 | 4 | 4900–4903 |

Retired as of April 2017, units were placed in storage,[59] pending disposition. |

|

EMD | GP40WH-2 | 19 | 51–69 |

Replaced by MP36PH-3Cs. Units 67–69 were rebuilt from GP40 work locomotives 30–32. One unit, no. 68, remains for non-revenue work duty and rescue use only. Several units rebuilt into MPI MP32PH-Q for Central Florida's SunRail commuter train. |

|

EMD | E9AM | 10 | 60–69 | Ex-Burlington Northern Railroad. Units were originally built as E8As. 67–68 renumbered to 91–92. |

|

EMD | F9PH | 5 | 81–85 | Ex-Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Units were rebuilt by Morrison-Knudsen from former F7 locomotives. Former MDOT 7181–7185. |

.jpg.webp) | EMD | F7 APCU | 1 | 7100 | Ex-Baltimore & Ohio Railroad F7 #4553, converted into an APCU. In the early 2000s, this unpowered unit occasionally substituted for a cab car. In addition to serving as an all-purpose control unit, it also had a head-end power generator that supplied electricity to the train. 7100 is now preserved at the B&O Railroad Museum and is used in push pull service on the Baltimore and Ohio museum railroad tour.[60][61] |

Current

| Image | Manufacturer | Model | Quantity | Delivered | Car Numbers | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg.webp) |

Sumitomo/ Nippon Sharyo | MARC II | 60 |

MARC IIA

|

1985–1987 | Coaches: 7700–7715 Cabs: 7745–7756 |

|

|

MARC IIB

|

1991–1993 | Coaches: 7716–7735, 7791–7799 Cabs:7757–7762 |

| ||||

.jpg.webp) |

Kawasaki | MARC III | 63 |

|

1999–2001 | Coaches:

7800–7834 7870–7876 Cabs: 7845–7858 |

|

|

Bombardier | MARC IV | 54 |

|

2014 | Coaches:

8000–8038 Cabs: 8039–8054 |

|

Former

| Image | Manufacturer | Model | Quantity | Delivered | Car Numbers | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg.webp) |

Budd | RDC | 16 | Self propelled cars | 1984 (inherited at inception) | 1, 3, 8, 9, 11, 12, 20, 22, 23, 800, 9801, 9802, 9805, 9918, 9921, 9941 | Inherited from various railroads |

|

Budd | MARC I | 22 | Single level cars | 1984 (inherited at inception) | 100–114, 130–134,

140–149, 150–154, 160–169, 190–191[66] |

Ex-Pennsylvania Railroad, Norfolk and Western Railway, NJ Transit, and SEMTA. Some operate at the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad museum. |

.jpg.webp) |

Pullman Standard | Gallery cars | 12 | Bi-level coaches | 2004 | 7900–7911 | Ex-Metra gallery cars. Replaced by Bombardier MARC IV. [67] |

Incidents

1996

On February 16, 1996, during the Friday evening rush hour, an eastbound train headed to Washington Union Station via the Brunswick Line collided with the westbound Amtrak Capitol Limited headed to Chicago via Pittsburgh. The collision occurred at Georgetown Junction on a snow-swept stretch of track just west of Silver Spring, Maryland. The crash left 11 people dead aboard the MARC train. Three died of injuries suffered in the impact alone, with the rest succumbing to the ensuing smoke and flames or a combination of the two. Engineer Ricky Orr and conductors Jimmy Major Jr. and Jim Quillen were among the victims. Eight Jobs Corps students also were killed during the accident.

The NTSB report concluded that the MARC crew apparently forgot the approach signal aspect of the Kensington color-position signal after making a flag stop at Kensington station. The MARC train was operating in push mode with the cab control car out front. The Amtrak locomotives were in the crossover at the time of the collision; the MARC cab control car collided with the lead Amtrak unit, F40PH #255, rupturing its fuel tank and igniting the fire that caused most of the casualties. The second unit was a GE Genesis P40DC #811, a newer unit that has a fuel tank that is shielded in the center of the frame. The official investigation also suggests that the accident might have been prevented if a human-factors analysis had been conducted when modifications to the track signaling system were made in 1992 with the closing of nearby QN tower.

2008

On February 7, 2008, a train derailed at Union Station after it was hit by an Amtrak switcher locomotive. The train was still unloading passengers at the time of impact, and seven people received minor head and neck injuries. The Amtrak locomotive was attempting to couple to the train and was reportedly moving too fast.

2010

Two significant events in 2010 received official response.

On June 21, 2010, northbound Amtrak-operated Penn Line train 538 broke down at 6:23 p.m. Temperatures inside the train reached 100 °F (38 °C) due to malfunctioning air conditioning. After passengers called 911, 10 people were treated at the scene for heat-related problems. All passengers were cleared from the scene by 9:40 pm.[68] This incident prompted MDOT Secretary Beverley Swaim-Staley to apologize to the affected customers on June 27, 2010.

On June 28, 2010, an Amtrak engineer operating a MARC train overran a scheduled stop in Odenton, without notice to passengers. Secretary Swaim-Staley was aboard the train at the time, and issued public statements about the situation. Amtrak CEO Joseph H. Boardman apologized to riders the following morning.[69]

This pair of events prompted Amtrak to draft an emergency response plan for broken down MARC trains.[70]

Proposals for service expansion

2007 plan

In the first decade of the 21st century, MARC ridership increased significantly, and the system neared capacity for its current configuration. With the area population growing and the BRAC process poised to bring new jobs to Aberdeen Proving Ground and Ft. Meade, both near MARC stations, the state saw the need to expand service. In September 2007, MTA Maryland unveiled an ambitious 30-year plan of system improvements. Though funding sources had not been established at that time, the plan represented the state's goals of increasing capacity and flexibility. Proposed improvements included:[71]

- Acquisition of new equipment. 54 Bombardier MultiLevels were ordered to replace aging single-level cars.

- Weekend service on the Penn Line. Service began on December 7, 2013, between Baltimore and Washington, D.C., with some trips extending to Martin State Airport. There are nine round trips on Saturdays (three begin and three then later end at Martin State Airport) and 6 round trips on Sundays (two begin and two then later end at Martin State Airport).[7]

- Increased mid-day service and reverse commute service on the Camden and Brunswick Lines. As of 2015, there is a somewhat limited reverse commute service in effect on the Camden Line.

- Extension of service past Union Station in Washington to L'Enfant and Northern Virginia along tracks used by VRE trains, thus relieving pressure on the Washington Metro

- More daily trips east of Baltimore's Penn Station, including improved service to Aberdeen Proving Ground

- Service beyond Perryville to Newark or Wilmington in Delaware, providing a connection to SEPTA commuter trains to Philadelphia and beyond

- New or expanded tunnels along the Northeast Corridor in Baltimore

- New stations in Baltimore, providing direct connections with the Metro Subway, and service to Johns Hopkins Hospital and Bayview Medical Center

- Rapid transit-like service through Baltimore

Some of the proposals were foreseen to take years or decades to implement, however others such as Penn Line weekend service could have begun in a matter of months, yet budgetary shortfalls prevented this. In Spring 2009, to offset such budget shortfalls, ticket sales employees at most non-Amtrak stations were replaced with Amtrak "Quik-Trak" touchscreen ticket machines, and some train services were eliminated or scaled back. Ticket machines were also added to stations that were not previously staffed, such as Halethorpe. The only remaining staffed stations, Odenton and Frederick, remained staffed by Commuter Direct.[72][73]

2010s: Extension to Delaware and SEPTA

In 2017, the Wilmington Area Planning Council submitted ridership studies to Cecil County, the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, SEPTA and the Delaware Department of Transportation for the extension of MARC service from Perryville via Elkton[74] to Newark, Delaware, and possibly Wilmington.[75] The section from Perryville to Newark is the one of only three along the Northeast Corridor not covered by commuter train service (the others are between New London, Connecticut, and Wickford Junction, Rhode Island as well as New York Penn Station and New Rochelle, New York). Currently a bus, Cecil Transit Route 5, connects the two stations.[76]

References

- "Transit Ridership Report Second Quarter 2016" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association. August 22, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2017 – via http://www.apta.com/resources/statistics/Pages/ridershipreport.aspx.

- "Transit Ridership Report Fourth Quarter 2015" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association. March 2, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2016 – via http://www.apta.com/resources/statistics/Pages/ridershipreport.aspx.

- "Transit Information Overview". Maryland Transit Administration. Retrieved June 24, 2011.

- Starcic, Janna (June 17, 2016). "Maryland's MARC Railroad Upgrades Fleet, Service to Bolster Ridership". Metro Magazine. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- "MARC Brunswick Line Timetable" (PDF). Maryland Transit Administration. March 13, 2017. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- "MARC Camden Line Timetable" (PDF). Maryland Transit Administration. March 13, 2017. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- "MARC Penn Line Full Timetable" (PDF). Maryland Transit Administration. March 4, 2019. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- Dilts, James D. (1996). The Great Road: The Building of the Baltimore and Ohio, the Nation's First Railroad, 1828–1853. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-8047-2629-0.

- Stakem, Patrick H. (2008). Maryland Area Rail Commuter, A Rider's Guide. PRB Publishing. ASIN B004U7FKQS.

- Stover, John F. (January 1, 1995). History of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Purdue University Press. ISBN 9781557530660.

- "Southern Maryland Commuter Rail Service Feasibility Study" (PDF). Maryland Transit Administration. August 2009.

- Baer, Christopher T. (April 2015). "A GENERAL CHRONOLOGY OF THE SUCCESSORS OF THE PENNSYLVANIA RAILROAD COMPANY AND THEIR HISTORICAL CONTEXT: 1902" (PDF). Pennsylvania Railroad Technical and Historical Society.

- Baer, Christopher T. (April 2015). "A GENERAL CHRONOLOGY OF THE SUCCESSORS OF THE PENNSYLVANIA RAILROAD COMPANY AND THEIR HISTORICAL CONTEXT: 1968" (PDF). Pennsylvania Railroad Technical and Historical Society.

- "Nationwide Schedules of Intercity Passenger Service". National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak). May 1, 1971. p. 6 – via The Museum of Railway Timetables.

- Baer, Christopher T. (April 2015). "A GENERAL CHRONOLOGY OF THE SUCCESSORS OF THE PENNSYLVANIA RAILROAD COMPANY AND THEIR HISTORICAL CONTEXT: 1971" (PDF). Pennsylvania Railroad Technical and Historical Society.

- Baer, Christopher T. (April 2015). "A GENERAL CHRONOLOGY OF THE SUCCESSORS OF THE PENNSYLVANIA RAILROAD COMPANY AND THEIR HISTORICAL CONTEXT: 1974" (PDF). Pennsylvania Railroad Technical and Historical Society.

- "History of MARC Train". Maryland Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on January 17, 2010.

- West Virginia Department of Transportation, State Rail Authority (March 12, 2013). "West Virginia State Rail Plan: Intercity Service Review". pp. 4–6. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014.

- "West Virginia State Rail Plan: Maryland Area Regional Commuter Service". West Virginia Department of Transportation, State Rail Authority. March 12, 2013. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- Baer, Christopher T. (April 2015). "A GENERAL CHRONOLOGY OF THE SUCCESSORS OF THE PENNSYLVANIA RAILROAD COMPANY AND THEIR HISTORICAL CONTEXT: 1980–89" (PDF). Pennsylvania Railroad Technical and Historical Society.

- Baer, Christopher T. (April 2015). "A GENERAL CHRONOLOGY OF THE SUCCESSORS OF THE PENNSYLVANIA RAILROAD COMPANY AND THEIR HISTORICAL CONTEXT: 1976" (PDF). Pennsylvania Railroad Technical and Historical Society.

- Baer, Christopher T. (April 2015). "A GENERAL CHRONOLOGY OF THE SUCCESSORS OF THE PENNSYLVANIA RAILROAD COMPANY AND THEIR HISTORICAL CONTEXT: 1977" (PDF). Pennsylvania Railroad Technical and Historical Society.

- Baer, Christopher T. (April 2015). "A GENERAL CHRONOLOGY OF THE SUCCESSORS OF THE PENNSYLVANIA RAILROAD COMPANY AND THEIR HISTORICAL CONTEXT: 1977" (PDF). Pennsylvania Railroad Technical and Historical Society.

- Shifrin, Carole (October 24, 1980). "BWI Airport Rail Link Celebrates Opening". The Washington Post. p. D3. ProQuest 147198286.

- "Commuter Trains' New Stop: Beltway Station". The Washington Post. August 11, 1982. p. MD11. ProQuest 147456718.

- Lynton, Stephen J. (June 9, 1983). "Baltimore-D.C. Commuter Train Trips to Increase". The Washington Post. p. B8. ProQuest 147548056.

- Fuchs, Tom (April 2009). "30th Anniversary of New Carrollton Station" (PDF). Transit Times. 23 (2): 5.

- "Metro Parking Spots Rented to Amtrak For Temporary Use at New Carrollton". The Washington Post. October 28, 1983. p. C12. ProQuest 147479061.

- "New New Carrollton station". Amtrak. 1983.

- McCord, Joel (April 28, 1984). "New station, schedule for rail users". Baltimore Sun – via Newspapers.com.

- "Bulletin Board". The Washington Post. May 28, 1981. p. MD9. ProQuest 147307755.

- Sargent, Edward D. (July 11, 1983). "Many Commute From Baltimore To District Jobs". Washington Post.

- Reid, Bruce (May 1, 1991). "Commuter rail, Perryville to Baltimore, starts today: MARC line's new Susquehanna Flyer out to attract commuters. ALL ABOARD!". The Baltimore Sun.

- Lee, Edward (July 24, 1993). "MARC plans to raise fares 19 percent boost to be proposed". The Baltimore Sun.

- Hedgpeth, Dana (June 22, 1995). "600 spaces to be added to MARC station parking lot by spring". The Baltimore Sun.

- Worden, Amy (August 3, 1989). "Columbia Commuters Get a Station Break: Convenience Touted at New MARC Stop in Savage Station Opens in Savage". The Washington Post. ProQuest 139977789.

- https://www.ebay.com/itm/MAY-1993-MARC-PENN-CAMDEN-BR-wbr-UNSWICK-LINES-PUBLIC-TIMETABLE-/372744447800?&_trksid=p2056016.m2518.l4276

- Meyer, Eugene L. (December 10, 1993). "LUKEWARM THRILL AT END OF LINE". The Washington Post.

- Jensen, Peter (January 18, 1994). "MARC is off to the races Jan. 31". The Baltimore Sun.

- Fehr, Stephen (December 12, 1994). "Commuter Lines Add Stations in Va. and Md". The Washington Post. p. D3. ProQuest 757194485.

- Spellmann, Karyn (July 8, 1996). "State DOT Considers New Road near Dulles". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on September 11, 2016 – via Highbeam Research.

- Logan, Mary (December 1, 2005). "MAJOR TRANSPORTATION MILESTONES IN THE BALTIMORE REGION SINCE 1940" (PDF). Baltimore Metropolitan Council. p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 27, 2010.

- "News and Upcoming Events" (PDF). Transit Times. Action Committee for Transit. 1 (2). Summer 1987.

- "Md. Commuters Get Another Way to Go". The Washington Post. July 9, 1987. ProQuest 139235759.

- "MARC to seek new operator for CSX-run routes". Trains Magazine. June 14, 2010. Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- Shaver, Katherine (July 7, 2010). "Holocaust group faults VRE contract". The Washington Post.

- "No way to run a railroad". WBAL TV. March 3, 2011. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- Phillips, Don (July 2011). "Lawsuits, Commuter Trains and the Holocaust". Trains. p. 11.

- Lind, Michael (June 5, 2011). "No way to run a railroad". The Washington Post.

- Rubin, Neil (February 10, 2012). "State archivist SNCF archives might not be enough". Baltimore Jewish Times.

- Sohr, Nicholas (November 21, 2011). "MD MTA Keolis mum on bids to run MARC lines". The Daily Record via masstransitmag.com.

- Weir, Kytja (October 17, 2012). "Bombardier wins $204m MARC commuter train contract". The Washington Examiner. Retrieved October 28, 2012.

- Shaver, Katherine (October 17, 2012). "New company to operate some MARC trains". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- "Maryland Rail Commuter Roster". www.thedieselshop.us. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- "MTA Expands MARC Penn Line Service". MTA Maryland Service Information. Archived from the original on March 31, 2009. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- "Board Of Public Works Approves $58 Million Contract For Eight MARC Locomotives" (Press release). Baltimore, Maryland: Maryland Transit Administration. September 17, 2015. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

- "MARC Riders Advisory Council Meeting Summary Minutes" (PDF). MTA Maryland. January 18, 2018. Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- "Penn Line schedule change: April 23". MTA Maryland. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- "MARC Riders Advisory Council Meeting Minutes" (PDF). MTA Maryland. April 20, 2017. Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- "The MARC 7100 Returns! (November 1999 CSX Railfan Magazine)". TrainWeb. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- http://www.borail.org/7100.aspx

- "Maryland Mass Transit Administration MARC-III Bi-level Coaches". www.kawasakirailcar.com. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- "MARC Train Awards $36.8 Million Contract to Bombardier Transportation to Overhaul 63 Bi-Level Rail Cars" (Press release). Baltimore, MD: Maryland Transit Administration. February 4, 2016.

- Michael Dresser (August 20, 2008). "New cars may ease MARC crowding". The Baltimore Sun. pp. 1B, 6B.

- "Governor O'Malley Announces Marc to Purchase 54 Multi-level Passenger Cars". MTA Maryland. November 2, 2011. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- Amtrak Employee Timetable, 1990

- Starcic, Janna (June 17, 2016). "Maryland's MARC Railroad Upgrades Fleet, Service to Bolster Ridership". Metro. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- Shaver, Katherine (June 23, 2010). "900 riders stuck on MARC train for more than two hours with no air conditioning". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- Dresser, Michael (June 30, 2010). "Md. transportation secretary calls for MARC review after recent lapses". Washington Post. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- Shaver, Katherine (July 1, 2010). "Amtrak unveils plan to dispatch help when MARC trains break down". The Washington Post. ISSN 0740-5421. Retrieved July 7, 2010.

- "MARC Growth & Investment Plan" (PDF). MTA Maryland. September 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2009. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- "Odenton station is now a Commuter Direct Store". MTA Maryland. September 2009.

- "Commuter Direct Store Locations". Commuter Direct. March 2015.

- Kroner, Brad (April 28, 2017). "MARC stop in Elkton moves forward, Perryville MARC facility stalls". Cecil Whig. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- Kroner, Brad (March 7, 2017). "Study to examine extending MARC line to Newark". Newark Post (Delaware). Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- Fixed Route 5 (schedule). Cecil Transit. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to MARC Train. |