Battle of Mulhouse

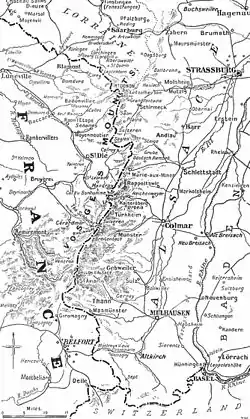

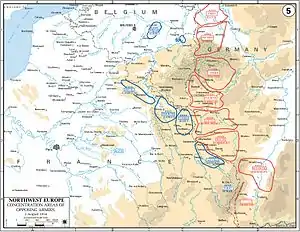

The Battle of Mulhouse (German: Mülhausen), also called the Battle of Alsace (Bataille d'Alsace), which began on 7 August 1914, was the opening attack of the First World War by the French Army against Germany. The battle was part of a French attempt to recover the province of Alsace, which France had ceded to the new German Empire following defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871. The French occupied Mulhouse on 8 August and were then forced out by German counter-attacks on 10 August. The French retired to Belfort, where General Louis Bonneau, the VII Corps commander, was sacked along with the commander of the 8th Cavalry Division. Events further north led to the German XIV and XV corps being moved away from Belfort and a second French offensive by the French VII Corps, reinforced and renamed the French Army of Alsace (General Paul Pau), began on 14 August.

| Battle of Mulhouse (Mülhausen) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of the Frontiers on the Western Front of the First World War | |||||||

Operations in Alsace, 1914 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

First Army VII Corps (45,000 men) Army of Alsace |

7th Army XIV and XV Corps (30,000 men engaged) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,500 PoW | 3,000 PoW | ||||||

Mulhouse Mulhouse, now a city and commune in eastern France, near the Swiss and German frontiers | |||||||

During the Battle of Lorraine, the principal French offensive by the First and Second armies, the Army of Alsace advanced cautiously into the border province of Lorraine (Lothringen). The French reached the area west of Mulhouse by 16 August and fought their way into the city by 19 August. The German survivors were pursued eastwards over the Rhine and the French took 3,000 prisoners. Joffre ordered the offensive to continue but by 23 August, preparations were halted as news of the French defeats in Lorraine and the Ardennes arrived. On 26 August, the French withdrew from Mulhouse to a more defensible line near Altkirch, to provide reinforcements for the French armies closer to Paris. The Army of Alsace was disbanded, the VII Corps was transferred to the Somme area in Picardy and the 8th Cavalry Division was attached to the First Army, to which two more divisions were sent later. The German 7th Army took part in the counter-offensive in Lorraine with the German 6th Army and in early September was transferred to the Aisne.

Background

Belgium

Belgian military planning assumed that if there was an invasion, the guaranteeing powers of Belgian neutrality would evict the invaders. The Belgian state did not see France and Britain as allies and Belgium intended only to protect its independence. The Anglo-French Entente (1904) led the Belgians to believe that the British saw Belgium as a British protectorate. A Belgian General Staff was formed in 1910 but the Chef d'État-Major Général de l'Armée, Lieutenant-Général Harry Jungbluth, was retired on 30 June 1912 and was replaced only in May 1914, by Lieutenant-Général Antonin de Selliers de Moranville. He began planning for the concentration of the army in the centre of the country and met with railway officials on 29 July.[1]

The field army was to assemble in front of the National redoubt of Belgium, ready to face any border, while the Fortified Position of Liège and Fortified Position of Namur were left to secure the frontiers. On mobilisation, the King became Commander-in-Chief and chose where the army was to concentrate. Amid the disruption of the new rearmament plan, the disorganised and poorly-trained Belgian soldiers would benefit from a central position to delay contact with an invader. The army would also need fortifications for defence but they were on the frontier and there was a school of thought that wanted a return to a frontier deployment, in line with French theories of the offensive. Belgian plans became an unsatisfactory compromise, in which the field army concentrated behind the Gete river with two divisions forward at Liège and Namur.[1]

Schlieffen–Moltke Plan

German strategy had given priority to offensive operations against France and a defensive posture against Russia since 1891. German planning was determined by numerical inferiority, the speed of mobilisation and concentration and the effect of the vast increase of the power of modern weapons. Frontal attacks were expected to be costly and protracted, leading to limited success, particularly after the French and Russians modernised their fortifications on the frontiers with Germany. Alfred von Schlieffen Chief of the Imperial German General Staff (Oberste Heeresleitung, OHL) from 1891–1906, devised a plan to evade the French frontier fortifications with an offensive on the northern flank, which would have a local numerical superiority and obtain rapidly a decisive victory. By 1898–1899, such a manoeuvre was intended to rapidly pass through Belgium, between Antwerp and Namur and threaten Paris from the north.[2]

Helmuth von Moltke the Younger succeeded Schlieffen in 1906 and was less certain that the French would conform to German assumptions. German strategy would need to become more opportunistic, and Moltke modified German plans, to make them less rigid, making the offensives of 1914 the opening moves of what was expected to be a long war with no certainty of victory.[3] Moltke adapted the deployment and concentration plan, to accommodate an attack in the centre or an enveloping attack from both flanks, by adding divisions to the left flank opposite the French frontier, from the c. 1,700,000 men expected to be mobilised in the Westheer (western army). The main German force would still advance through Belgium and attack southwards into France, the French armies would be enveloped on the left and pressed back over the Meuse, Aisne, Somme, Oise, Marne and Seine, unable to withdraw into central France. The French would be annihilated, or the manoeuvre from the north would create conditions for victory in the centre or in Lorraine.[4]

Plan XVII

Under Plan XVII, the French peacetime army was to form five field armies of c. 2,000,000 men, with "Groups of Reserve Divisions" attached to each army and a Group of Reserve Divisions on each of the extreme flanks. The armies were to concentrate opposite the German frontier around Épinal, Nancy and Verdun–Mezières, with an army in reserve around Ste Ménéhould and Commercy. Since 1871, railway building had given the French General Staff sixteen lines to the German frontier, against the thirteen available to the German army, and the French could wait until German intentions were clear. The French deployment was intended to be ready for a German offensive in Lorraine or through Belgium. It was anticipated that the Germans would use reserve troops but also expected that a large German army would be mobilised on the border with Russia, leaving the western army with sufficient troops only to advance through Belgium south of the Meuse and the Sambre rivers. French intelligence had obtained a map exercise of the German general staff of 1905, in which German troops had gone no further north than Namur and assumed that plans to besiege Belgian forts were a defensive measure against the Belgian army.[5]

A German attack from south-eastern Belgium towards Mézières and a possible offensive from Lorraine towards Verdun, Nancy and St Dié was anticipated; the plan was an evolution from Plan XVI and made more provision for the possibility of a German offensive through Belgium. The First, Second and Third armies were to concentrate between Épinal and Verdun opposite Alsace and Lorraine, the Fifth Army was to assemble from Montmédy to Sedan and Mézières and the Fourth Army was to be held back west of Verdun, ready to move east to attack the southern flank of a German invasion through Belgium or southwards against the northern flank of an attack through Lorraine. No formal provision was made for combined operations with the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), but joint arrangements had been made, In 1911, during the Second Moroccan Crisis, the French had been told that six divisions could be expected to operate around Maubeuge.[6]

Declarations of war

At midnight on 31 July – 1 August, the German government sent an ultimatum to Russia and announced a state of Kriegsgefahr. During the day, the Ottoman government ordered mobilisation, and the London Stock Exchange was closed. On 1 August, the British government ordered the mobilisation of the navy, and the German government ordered general mobilisation and declared war on Russia. Hostilities commenced on the Polish frontier, the French government ordered general mobilisation, and the next day, the German government sent an ultimatum to Belgium, demanding passage through Belgian territory, as German troops crossed the frontier of Luxembourg. Military operations began on the French frontier, Libau was bombarded by a German light cruiser SMS Augsburg and the British government guaranteed naval protection for French coasts. On 3 August, the Belgian government refused German demands and Britain guaranteed military support to Belgium if Germany invaded. Germany declared war on France, the British government ordered general mobilisation and Italy declared neutrality. On 4 August, the British government sent an ultimatum to Germany and declared war on Germany at midnight on 4–5 August, Central European Time. Belgium severed diplomatic relations with Germany, and Germany declared war on Belgium. German troops crossed the Belgian frontier and attacked Liège.[7]

Prelude

German preparations

In 1908, Moltke began to alter plans for operations on the left wing of the German armies against France and chose XIV Corps to protect Upper Alsace and several Landwehr brigades to secure the Upper Rhine. Later plans added forces to the region and by 1909, the 7th Army had three corps and a reserve corps, with two corps from Wissembourg to Saverne and Strasbourg, one corps on the west (left bank) of the Rhine from Colmar to Mulhouse and the reserve corps on the east (right bank) of the Rhine. The 6th Army was to assemble between Metz and Sarrebourg in Lorraine, massing eight corps on the left wing of the German armies in the west (Westheer), which with fortress garrisons and Landwehr troops, changed the ratio of forces between the left and right wings of the Westheer from 7:1 to 3:1. Moltke added forces to the left wing after concluding that a possible French offensive into Alsace and Lorraine, particularly from Belfort, had become a certainty. The 7th Army was to defeat an offensive in Alsace and co-operate with the 6th Army to defeat an offensive in Lorraine. After 1910, the 7th Army was to attack with the 6th Army towards the Moselle below Frouard and the Meurthe; provision was also made for the movement of troops to the right wing of the German armies by reserving trains and wagons in the region.[8]

The deployment plan for the Westheer allocated to the 7th Army (Generaloberst Josias von Heeringen) the XIV and XV corps, the XIV Reserve Corps and the 60th Landwehr Brigade, to deploy from Strasbourg to Mulhouse and Freiburg im Breisgau and the command of fortresses at Strasbourg and Neuf-Brisach. The 1st and 2nd Bavarian brigades, 55th Landwehr Brigade, Landwehr Regiment 110 and a battery of heavy field howitzers were also added to the army under the provisional command of the XIV Corps commander.[9] In 1914, the Swiss frontier was guarded by XIV Corps with the 58th Brigade and by XV Corps from Donon to the Rheinkopf, with several infantry regiments, Jäger battalions, some artillery and cavalry. The mobilisation and deployment was completed from 8 to 13 August but the German troops were concentrated further north than anticipated, to be ready to meet a French offensive from Belfort with concentric counter-attacks from the north and east.[10]

French preparations

The 1re Armée (First Army) mobilised with the VII, VIII, XIII, XXI, XIV corps and the 6th Cavalry Division. VII Corps, with the 14th and 41st divisions, a brigade of the 57th Reserve Division from Belfort and the 8th Cavalry Division, was detached from the First Army on 7 August for independent operations in southern Alsace.[11] An attack into Alsace would begin the redemption of the lost provinces and demonstrate to Russia that the French army was fighting the common enemy. Bonneau reported a large concentration of German troops in the area and recommended delay but Joffre over-ruled him and ordered the attack to commence. Joffre issued General Order No. 1 on 8 August, in which the operation by VII Corps was to pin down the German forces opposite and to attract reserves away from the main offensive further north.[12]

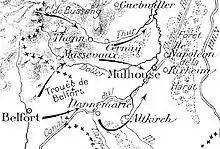

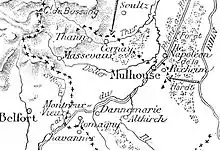

Battle

A few border skirmishes took place after the declaration of war and German reconnaissance patrols found that the French had a chain of frontier posts, supported by larger fortified positions further back. After 5 August, more patrols were sent out as French troops advanced from Gérardmer to the Col de la Schlucht (Schlucht Pass), where the Germans retreated and blew up the tunnel.[10] Joffre had directed the First and Second armies to engage as many German divisions as possible to assist French forces operating further north. The French VII Corps (General Louis Bonneau) with the 14th Division (General Louis Curé), the 41st Division (General Paul Superbie) with the 8th Cavalry Division (General Louis Aubier) on the flank.[13] The French advanced from Belfort to Mulhouse and Colmar 35 km (22 mi) to the north-east but were hampered by the breakdown of the supply service and delays. The French seized the border town of Altkirch 15 km (9.3 mi) south of Mulhouse with a bayonet charge for a loss of 100 men killed.[14][lower-alpha 1]

On 8 August, Bonneau cautiously continued the advance and occupied Mulhouse, shortly after the German 58th Infantry Brigade retreated.[13] The First Army commander, General Auguste Dubail, preferred to dig in and wait for mobilisation to finish but Joffre ordered the advance to continue. In the early morning of 9 August, parts of the XIV and XV Corps of the German 7th Army arrived from Strasbourg and counter-attacked at Cernay. The German infantry emerged from the Hardt forest and advanced into the east side of the city. Communication on both sides failed and both fought isolated actions, the Germans making costly frontal attacks. As night fell, German troops at the suburb of Rixheim, east of Mulhouse, inexperienced German troops fired wildly, wasting huge amounts of ammunition and occasionally shooting at each other, one regiment suffering 42 men killed, 163 wounded and 223 missing.[16] Mulhouse was recaptured on 10 August and Bonneau withdrew towards Belfort.[17] Further north, the French XXI Corps made costly attacks on mountain passes and were forced back from Badonviller and Lagarde, where the 6th Army took 2,500 French prisoners and eight guns; civilians were accused of attacking German troops and subjected to reprisals.[18]

Joffre put General Paul Pau in command of a new Army of Alsace and sacked (Limogé) Bonneau. The new army was reinforced with the 44th Division, the 55th Reserve Division, the 8th Cavalry Division and the 1st Group of Reserve Divisions (58th, 63rd and 66th Reserve divisions), to re-invade Alsace on 14 August as part of the larger offensive by the 1re Armée and 2e Armée into Lorraine. Rupprecht of Bavaria planned to move two corps of the 7th Army towards Sarrebourg and Strasbourg; Heeringen objected because the French had not been decisively defeated but most of the 7th Army was moved north. The Army of Alsace began the new offensive against four Landwehr brigades.[19]

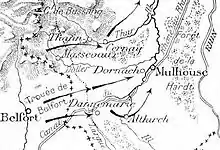

The Landwehr fought a delaying action as the French advanced from Belfort with two divisions on the right passing through Dannemarie at the head of the valley of the Ill river. On the left flank, two divisions advanced with Chasseur battalions, which had moved into the Fecht valley on 12 August. On the evening of 14 August, Thann was captured. The most advanced troops had passed beyond the suburbs of Cernay and Dannemarie on the western outskirts of the city by 16 August. On 18 August, VII Corps attacked Mulhouse and captured Altkirch on the south-eastern flank as the northern flank advanced towards Colmar and Neuf-Brisach.[19]

The Germans were forced back from high ground west of Mulhouse on both banks of the Doller and into the Mulhouse suburbs, where a house-to-house battle took place. The streets and houses of Dornach were captured systematically and by the evening of 19 August, the French again controlled the city. (The commander of the French 88th Division, General Louis Victor Plessier was mortally wounded in the battle at Zillisheim.)[20] After being overrun, the Germans withdrew hastily through the Hardt forest to avoid being cut off and crossed the Rhine pursued by the French, retreating to Ensisheim, 20 km (12 mi) to the north. The French captured 24 guns, 3,000 prisoners and considerable amounts of equipment.[19]

With the capture of the Rhine bridges and valleys leading into the plain, the French had gained control of Upper Alsace. The French consolidated the captured ground and prepared to continue the offensive but the German 7th Army was left free to threaten the right flank of the 1re Armée, which moved troops to the right flank. On 23 August, preparations were suspended as news arrived of the French defeats in Lorraine and Belgium and next day, the VII Corps was ordered to move to the Somme. On 26 August, the French withdrew from Mulhouse to a more defensible line near Altkirch, to provide reinforcements for the French armies closer to Paris and the 55th Landwehr Brigade re-occupied the town.[21] The Army of Alsace was disbanded and the 8th Cavalry Division was attached to the First Army, two more divisions being sent later.[19]

Aftermath

Analysis

Troops in the first French invasion of the war had encountered the extent of German firepower and the consequences of some of the flaws in the French army, which had an excess of elderly commanders, a shortage of regimental officers and was deficient in supplies of maps and intelligence. Despite tactical instructions stressing combined-arms operations and the importance of firepower, cavalry and infantry were poorly trained and attacked swiftly, with little tactical finesse. The German XIV and XV corps had been diverted from their concentration areas and by 13 August, had become exhausted and disorganised by the battle.[22] Those citizens of Alsace who unwisely celebrated the appearance of the French army, were left to face German reprisals.[23]

The Army of Alsace was dissolved on 26 August and many of its units distributed among the remaining French armies.[24] In a 2009 publication, Holger Herwig wrote that the French attacks at Mulhouse had been fought in the wrong place (the south) for the wrong reason (prestige). Joffre only wanted German forces pinned down in the south and the Germans wanted the same but the fog of war described by Clausewitz had descended.[25] In his 2014 edited translation of Die Schlacht in Lothringen und in den Vogesen 1914 by Karl Deuringer (1929) Terence Zuber wrote that the French official history concentrated on formations no smaller than corps, that army records of the operations are sparse, regimental histories are of limited value and there are no monographs.[26]

Casualties

Information on casualties during the fighting around Mulhouse is incomplete but during the first French advance, 100 men were killed in the capture of Altkirch.[27] In 2009, Holger Herwig wrote that on 10 August, the German Infantry Regiment 112 suffered 42 men killed, 163 wounded and 223 missing during the counter-attack on Mulhouse. The fighting on 19 August resulted in severe German casualties, one company being reduced from 250 men to sixteen.[28] It is also known that 2,500 French and 3,000 German troops were taken prisoner in the region of Mulhouse.[29]

Notes

- Having entered Mulhouse on 7 August 1914, General Joseph Joffre issued a proclamation: French Proclamation on Invasion of Alsace at Mulhouse 7 August 1914 CHILDREN of ALSACE! After forty-four years of sorrowful waiting, French soldiers once more tread the soil of your noble country. They are the pioneers in the great work of revenge. For them what emotions it calls forth, and what pride! To complete the work they have made the sacrifice of their lives. The French nation unanimously urges them on, and in the folds of their flag are inscribed the magic words, "Right and Liberty". Long live Alsace. Long live France. General-in-Chief of the French Armies, JOFFRE.[15]

Footnotes

- Strachan 2001, pp. 209–211.

- Humphries & Maker 2013, pp. 66, 69.

- Humphries & Maker 2013, p. 131.

- Strachan 2001, pp. 190, 172–173, 178.

- Strachan 2001, p. 194.

- Strachan 2001, pp. 195–198.

- Skinner & Stacke 1922, p. 6.

- Humphries & Maker 2013, pp. 75–76.

- Humphries & Maker 2013, pp. 81–82.

- Humphries & Maker 2013, p. 95.

- Tyng 2007, pp. 357, 61.

- Doughty 2005, pp. 56–57.

- Herwig 2009, p. 76.

- Doughty 2005, p. 57; Clayton 2003, p. 20.

- Times 1915, p. 387.

- Herwig 2009, pp. 77–78.

- Strachan 2001, pp. 211–212.

- Humphries & Maker 2013, p. 128.

- Michelin 1920, p. 37.

- Gehin & Lucas 2008, p. 432.

- Tyng 2007, pp. 131–132; Herwig 2009, p. 103.

- Koenig 1933, p. 7.

- Clayton 2003, p. 22.

- Tyng 2007, p. 357.

- Herwig 2009, p. 80.

- Zuber 2014, p. 10.

- Clayton 2003, p. 20.

- Herwig 2009, pp. 77–78, 89.

- Humphries & Maker 2013, p. 128; Michelin 1920, p. 37.

Bibliography

Books

- Clayton, A. (2003). Paths of Glory: The French Army 1914–18. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-35949-3.

- Doughty, R. A. (2005). Pyrrhic victory: French Strategy and Operations in the Great War. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01880-8.

- Gehin, Gérard; Lucas, Jean-Pierre (2008). Dictionnaire des Généraux et Amiraux Francais de la Grande Guerre [Dictionary of French Generals and Admirals of the Great War] (in French). II. Paris: Archives et Culture. ISBN 978-2-35077-070-3.

- Herwig, H. (2009). The Marne, 1914: The Opening of World War I and the Battle that Changed the World. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6671-1.

- L'Alsace et les Combats des Vosges 1914–1918: Le Balcon d'Alsace, le Vieil-Armand, la Route des Crêtes [Alsace and the Vosges Battles 1914–1918: The Balcony of Alsace, Old-Armand and the Ridge Road]. Guides Illustrés Michelin des Champs de Bataille (1914–1918) (in French). IV. Clemont-Ferrand: Michelin & Cie. 1920. OCLC 769538059. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- Humphries, M. O.; Maker, J. (2013). Der Weltkrieg 1914: The Battle of the Frontiers and Pursuit to the Marne. Germany's Western Front: Translations from the German Official History of the Great War. I. Part 1. Waterloo, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-1-55458-373-7.

- Skinner, H. T.; Stacke, H. Fitz M. (1922). Principal Events 1914–1918. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. London: HMSO. OCLC 17673086. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- Strachan, H. (2001). The First World War: To Arms. I. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926191-8.

- Tyng, S. (2007) [1935]. The Campaign of the Marne 1914 (Westholme, PA ed.). New York: Longmans, Green. ISBN 978-1-59416-042-4.

- Zuber, T., ed. (2014). The First Battle of the First World War: Alsace-Lorraine (cond. trans. ed. Deuringer, K. Die Schlacht in Lothringen und in den Vogesen 1914 die Feuertaufe der Bayerischen Armee. 2 Ereignisse nach dem 22. August [The Battle in Lorraine and the Vosges 1914: The Baptism of Fire of the Bavarian Army (II) Events to 22 August] Bayerische Kriegsarchiv, München, 1929 ed.). Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-6086-4.

Encyclopaedias

- "The Times History of the War". The Times. I. London. 1914–1921. OCLC 642276. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

Reports

- Koenig, E. F. (1933). Battle of Morhange–Sarrebourg, 20 August 1914 (PDF) (Report). CGSS Student Papers, 1930–1936. Fort Leavenworth, KS: The Command and General Staff School. OCLC 462117869. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

Websites

- "The Battle of Mulhouse". MilitaryHistoryWiki.org. Archived from the original on 20 September 2008. Retrieved 24 September 2008.

Further reading

- Ehlert, H.; Epkenhans, M.; Gross, G. P., eds. (2014) [2006]. The Schlieffen Plan: International Perspectives on the German Strategy for World War I [Der Schlieffenplan: Analysen und Dokumente]. Foreign Military Studies. Translated by Zabecki, D. T. (trans. ed.). Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-4746-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Mulhouse. |