Battle of Tug Argan

The Battle of Tug Argan was fought between forces of the British Empire and Italy from 11 to 15 August 1940 in British Somaliland (later the independent and renamed Somalia). The battle determined the result of the Italian conquest of British Somaliland after the Italian invasion and the larger East African Campaign of the Second World War.

| Battle of Tug Argan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the East African Campaign of the Second World War | |||||||

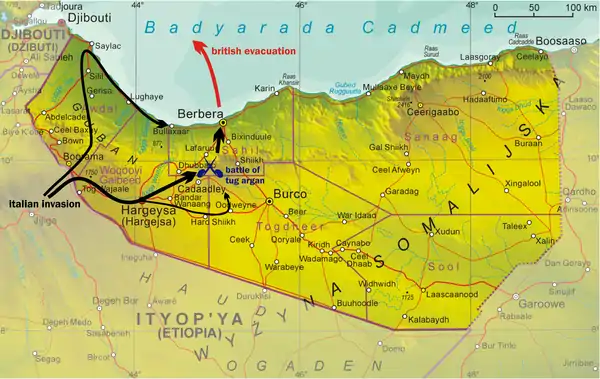

Map depicting the location of the Battle of Tug Agran and the British evacuation from Berbera | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5,000 regular and colonial infantry | At least 24,000 colonial troops with 5,000 Italian regulars | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

38 killed 102 wounded 120 missing 7 aircraft destroyed 5 artillery pieces captured 5 mortars captured[1] |

465 killed 1530 wounded 34 missing[1] | ||||||

Italian invasion forces were advancing northwards on a north-south road toward the colonial capital of Berbera through the Tug Argan gap (named after the dry riverbed tug running across it) in the Assa hills, when they encountered British units lying in fortified positions on a number of widely distributed hills across its breadth. Italian infantry, after an intense four-day encounter, overran the undermanned British positions and were able to seize the gap, compelling the defenders to withdraw to Berbera.

The Italian victory made the position of British forces in Somaliland untenable; the British colonial authorities evacuated the garrison by sea from Berbera. Italy was able to quickly secure the territory, an achievement whose propaganda value to a bellicose Fascist regime would ultimately outweigh its relatively minute strategic importance.

Background

As Italy entered the war at the conclusion of the Battle of France, its Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini looked to Africa for easy conquests to justify his entrance into the conflict and to glorify Italy's role. The remote colony of British Somaliland, a tract of modern Somalia poor in both resources and defenders, appeared vulnerable. Though Italy lacked the supply structure for a long war in the region, an expedition to Somaliland was authorised, set for late 1940. Italian forces in East Africa were relatively strong in numbers, if not in quality, with 29 colonial brigades, each comprising several infantry battalions and some light artillery, concentrated around the recently conquered Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa. The Italians also possessed at least 60 light and medium tanks as well as 183 fighter aircraft, light and medium bombers.[2]

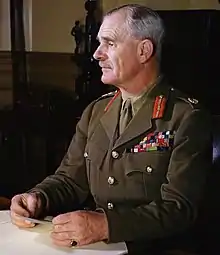

The British were outnumbered and their exiguous colonial forces were dispersed in North and East Africa. With Cyrenaica and the Sudan under threat as well as Somaliland, only token units were available to control what was considered a relatively unimportant possession, devoid of infrastructure, productive capacity or natural resources. Until December 1939 British policy had been to abandon Somaliland if there was an invasion. General Archibald Wavell, the new commander of British armies in Africa, persuaded the British Chiefs of Staff that Somaliland should be defended, for much the same motives as Italy drew upon in the attempt to seize it. A multiracial congregation of five battalions, the minimum force adjudged capable of defending the region, was assembled by the beginning of August.[3][4] The defence force included two Sikh battalions and the 2nd King's African Rifles, which arrived by sea in from Aden. The Indian units, contrary to expectations, were composed of well-equipped and professional soldiers, a much-needed complement to the inexperienced Rhodesian troops already present.[5]

Berbera, the capital of British Somaliland and its only major city and port, was the obvious destination of any invasion. As plans took shape for the blocking of Italian passage to the city, it became apparent that the border with Ethiopia was too long and open to be defended. The rugged Somali countryside (as is pictured below) was impassable by vehicles, meaning that the British could defend bottlenecks on the two roads to Berbera, which wound through the desert via the towns of Hargeisa and Burao, respectively. The Hargeisa road, the most direct route to the capital, was most easily blocked at the Tug Argan gap in the Assa hills. The pass was flat and open; a small force could not hold out for long against superior numbers but despite this topographical disadvantage, three battalions of the five originally allocated and a light artillery battery were committed to the defence of Tug Argan. Another battalion was held in reserve.[6]

The strategic position of the British was undermined by the Battle of France and the French surrender on 22 June. British planners had anticipated fighting with the French, who controlled the western quarter of the Somali coast and had relinquished military control of the border regions adjoining the two protectorates. France had a larger garrison in Somaliland than Britain and could obtain reinforcements from Madagascar. Though the armistice had been signed at Compiègne, General Paul Le Gentilhomme, Commander-in-Chief of French East African forces, announced that he would not join Vichy France in neutrality, proposing instead to continue the struggle from Djibouti. Le Gentilehomme was relieved of command by his superiors on 22 July and he fled to Allied territory. His successor soon achieved détente with the Italians, leaving British Somaliland isolated.[7]

On 3 August, General Guglielmo Nasi led 35,000 Italian troops, the vast majority of them African conscripts, across the border from their staging point at Harar into British Somaliland. The invaders were organised into three columns: one on the left, which would advance north to the coast at Zeila—a route recently vacated by the Vichy French before turning east to Berbera; one on the right, which would make the opposite motion on the Burao road and a main central column, led by Carlo de Simone, containing the bulk of his forces. Simone was to capture the British positions at Tug Argan and make straight for Berbera, ending the campaign with a decisive battle.[5] The Italians captured Hargeisa on 6 August, forcing British camel soldiers to withdraw completely. A few days of rest and rearmament ensued before the march was resumed on 8 August. The delay was extended by administrative inertia, as Italian officers complained of heavy rains and impassable roads. Following two days of probing, de Simone and his contingent reached the head of the Tug Argan gap and an initial assault was scheduled for 11 August. General Alfred Godwin-Austen arrived to take command of the British garrison from Arthur Chater, who would remain in local control of the Tug Argan front.[8][9]

Battle

Having realised that holding Tug Argan was essential to halting any invasion, British command poured all available resources—though diminished by French duplicity—into its defence. A unit of the Black Watch was rushed to the village of Laferug (to the rear of the gap) late on 10 August by truck, and a brigade headquarters was established at nearby Barkasan. Meanwhile, those battalions already present entrenched themselves across the broad arc of the gap.[9] On the British right were positioned three companies of the 3/15 Punjab Regiment, holding a group of southwest-facing strongpoints overlooking the rough wilderness beside the road. The British left was covered by another group of Indian troops, facing directly southward from atop the aptly named 'Punjab Ridge.'[1] The gap itself was manned by the more numerous Rhodesian line infantry. They sat upon a line of rocky knolls, named from north to south Black, Knobbly, Mill, Observation, and Castle Hills, positioned in a ragged diagonal echelon with 2,000–2,500 yard gaps between them across the mouth of the gap. Each was a miniature fortress, housing machine-gun nests surrounded by concentric rings of barbed wire. These strongpoints were keystones in the British arch; fall, and the line would crumble. Given that the front was far too wide for the troops available and the gaps between the hills too large, maintaining this balance in the face of enemy numbers was shaping up to be a difficult task. Worse, the linear arrangement of the mounds denied the British position meaningful depth, thereby increasing its vulnerability to individual Italian breakthroughs.[10]

Late on 10 August, the first signs of Italian preparations became apparent to the defenders of Tug Argan. Through the day, the headlights of advancing Axis supply convoys were clearly visible, and Somali refugees, fleeing before De Simone's column, swarmed across the Mirgo Pass on the British left. A K.A.R. patrol skirmished briefly with a quartet of Italian armoured cars, but the exchanged gunfire terrified the British camels and forced their riders to flee.[11] After receiving word from other scouts that the Italian tanks and infantry were easily avoiding the crude minefields laid before the creek, all Allied forces still holding the forward trenches were withdrawn to the prepared battle line. As this manoeuvre was nearing completion, Italian artillery and aircraft initiated a preliminary bombardment of the hills, and parties of second-rate Ethiopian and Blackshirt troops made a series of futile sallies through the early evening.[12] In the meantime, De Simone deployed his main forces opposite the British positions a move that presaged a traditional set battle. On the Italian left, II Brigade prepared to advance through the wilderness towards the Punjab troops in the north. In the centre, XIV Brigade faced the Rhodesian hilltop positions within the pass, and XV Brigade looked north towards Punjab Ridge on the Italian right. Behind them were XIII Brigade and the armoured vehicles.[1]

The attack on the gap began at 7:30 am on 11 August, as a flight of Savoia-Marchetti SM.81 medium bombers attacked British defenders on Punjab Ridge. This half-hour assault was followed by a long artillery bombardment lasting until noon. At 12:30, the infantry attack began. II Brigade began moving slowly towards the Indians through the trackless wilderness north of the road, XIV Brigade attacked Mill, Knobbly, and Observation Hills, and XV Brigade clambered atop Punjab Ridge, engaging its defenders. The attacks of XIV Brigade against the Rhodesians failed, but XV Brigade managed to drive off the Indian defenders of Punjab Ridge. Counterattacks were mounted against the Italians, but these were unsuccessful.[1][13] The Italian attack on the hills was renewed the next day (12 August). Black, Knobbly, and Mill Hills endured repeated assaults by XIV Brigade, and the weakest of them, Mill Hill, began to reel under the sustained pressure. By 4:00 pm, the British defences were being overrun, and after nightfall the British retreated from the hill, spiking their guns as they left.[1]

Kenyan troops of the King's African Rifles, who played a prominent role on the British side at Tug Argan

13 August saw little change in the overall situation. XIV Brigade's attacks on the Rhodesian hilltop positions failed yet again after some intense fighting, while II Brigade continued their trek through the wilderness toward the northern hills. XV Brigade began to infiltrate behind British lines, finding a supply convoy, which was attacked and dispersed.[1] On 14 August, the embattled XIV Brigade was relieved of their role in the battle after suffering heavy casualties in their continuous offensives, and was replaced by XIII Brigade. The fresh troops attacked Observation Hill but failed again, even after continuous artillery bombardment throughout the day. II Brigade, meanwhile, had still failed to engage the Indians, and XV Brigade made little progress before fending off a counterattack from two companies of the 2nd King's African Rifles.[13]

By 14 August, Godwin-Austen had realised his peril. XV Brigade was encircling him from the rear, his troops were exhausted, and his artillery units—some already abandoned to the advancing Italians—were running low on ammunition. He informed General Henry Maitland Wilson, in command at Cairo while Wavell was absent in England, that retreat from Tug Argan and evacuation from British Somaliland was now a necessity. If his forces could be evacuated, perhaps 70 percent of them might be removed. Otherwise, he would be forced either to fight to the death or to surrender his men and munitions. Wilson agreed to Godwin-Austen's request the next day, and preparations were made to flee after dark on 15 August.[14] During that day, Observation Hill was attacked for the final time by De Simone's forces. De Simone had decided to continue the attack in the gap in lieu of completing the flanking manoeuvre, and this final push proved successful. By 7:00 pm, XIII Brigade had seized Observation Hill, from which the British retreated in disarray. After sundown, the defenders of the remaining hills were withdrawn, along with the Punjab troops, who departed just as II Brigade was able to make inroads through their deserted positions. British resistance had collapsed, and as Godwin-Austen and his forces fled towards Berbera, the Italians seized control of the Tug Argan Gap.[1]

Following the British withdrawal from Tug Argan, the Italians swiftly completed the investment of Berbera. To permit the main body of the colonial garrison to reach the coast, units of the Black Watch, 2nd Battalion King's African Rifles and the 1/2 Punjab Regiment formed a small rearguard at Barakasan, which fought into the night of 17 August.[15] The Royal Navy had already begun to evacuate military personnel from Berbera on 16 August, operations that few Italian aircraft flew against, possibly due to uncertainty about whether a peace treaty might be signed. By 19 August, all remaining British military forces, including the rearguard, the last of which had embarked late the previous day, had been evacuated by sea.[16] An estimated 5,300–5,700 troops reached Aden.[17] Italian forces, which had been held up by naval bombardment by HMS Ceres on 17 August, arrived in a deserted Berbera on 19 August. This final advance marked the fall of British Somaliland was almost certainly inevitable.[1]

Aftermath

Analysis

The retreat from Somaliland, despite the prudent conduct of local commanders, infuriated British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Irritated by Mussolini's boasting, Churchill excoriated Wavell via cable, labelling the low casualty numbers on the British side a mark of blatant cowardice and demanding that Godwin-Austen be subjected to a board of inquiry. Wavell replied with "a big butcher's bill is not necessarily evidence of good tactics"—further enraged Churchill, under whose influence the general's promising career stuttered.[18] Despite the emotional attachments professed by Allied and Axis leaders to the rule of Somaliland, few spoils changed hands as a result of Italian victory. Defeat was a blow to British prestige and pride but the territory had little significance to imperial strategy. Britain gained financially after being relieved of the burden of providing a garrison. The impact could have been far greater if the Italians had managed to move faster after the battle. Heavy rains and difficulties supplying the troops damaged these efforts, removing any chance of a strategic victory.[19]

Casualties

The British suffered 38 dead, 102 wounded, and 120 missing; ten artillery pieces were left behind. Italian casualties were 465 dead, 1,530 wounded and 34 missing.[1]

See also

References

- Stone 1998.

- Playfair 1954, pp. 165–166.

- Playfair 1954, pp. 171–173.

- Mackenzie 1951, p. 22.

- Mockler 2003, p. 243.

- Playfair 1954, p. 173.

- Moyse-Bartlett, p. 494.

- Playfair 1954, p. 174.

- Mockler 2003, p. 245.

- Playfair 1954, p. 175.

- Moysse-Bartlett 2012, pp. 497-8.

- Stewart 2016, p. 78.

- Playfair 1954, p. 176.

- Playfair 1954, pp. 176–177.

- Wavell 1946, p. 2,724.

- Stewart 2016, p. 87.

- Tucker 2005, p. 1179.

- Pitt 2004, pp. 48–49.

- Stewart 2016, pp. 93–94.

Sources

- Mackenzie, Compton (1951). Eastern Epic: September 1939 – March 1943: Defence. I. London: Chatto & Windus. OCLC 59637091.

- Mockler, Anthony (2003). Haile Selassie's War. Signal Books. ISBN 978-1-902669-53-3.

- Moyse-Bartlett, Lieutenant-Colonel H. (2012). The King's African Rifles. II. Andrews UK Limited. ISBN 978-1-78150-663-9.

- Pitt, Barrie (2004). Churchill and the Generals. Barnsley: Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-101-1.

- Playfair, Major-General I. S. O.; et al. (1954). Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East: The Early Successes Against Italy (to May 1941). History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. I. London: HMSO. OCLC 494123451. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- Stewart, Andrew (2016). The First Victory: The Second World War and the East Africa Campaign. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-20855-9.

- Tucker, Spencer (2005). World War II. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-857-6.

- Wavell, A. (1946). Operations in the Somaliland Protectorate, 1939–1940 (Appendix A – G. M. R. Reid and A. R. Godwin-Austen). London: London Gazette. published in "No. 37594". The London Gazette. 4 June 1946. pp. 2719–2727.