Bill Rowling

Sir Wallace Edward Rowling KCMG PC (/ˈroʊlɪŋ/; 15 November 1927 – 31 October 1995), commonly known as Bill Rowling, was a New Zealand politician who was the 30th Prime Minister of New Zealand from 1974 to 1975. He held office as the parliamentary leader of the Labour Party.

Sir Wallace Rowling | |

|---|---|

Rowling in 1962 | |

| 30th Prime Minister of New Zealand | |

| In office 6 September 1974 – 12 December 1975 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Governor-General | Denis Blundell |

| Deputy | Bob Tizard |

| Preceded by | Norman Kirk |

| Succeeded by | Robert Muldoon |

| 33rd Minister of Finance | |

| In office 8 December 1972 – 6 September 1974 | |

| Prime Minister | Norman Kirk |

| Preceded by | Robert Muldoon |

| Succeeded by | Bob Tizard |

| 22nd Leader of the Opposition | |

| In office 12 December 1975 – 3 February 1983 | |

| Preceded by | Robert Muldoon |

| Succeeded by | David Lange |

| 8th Leader of the New Zealand Labour Party | |

| In office 6 September 1974 – 3 February 1983 | |

| Deputy | Bob Tizard |

| Preceded by | Norman Kirk |

| Succeeded by | David Lange |

| 22nd President of the Labour Party | |

| In office 5 May 1970 – 8 May 1973 | |

| Preceded by | Norman Douglas |

| Succeeded by | Charles Bennett |

| Member of the New Zealand Parliament for Buller | |

| In office 7 July 1962 – 25 November 1972 | |

| Preceded by | Jerry Skinner |

| Member of the New Zealand Parliament for Tasman | |

| In office 25 November 1972 – 14 July 1984 | |

| Succeeded by | Ken Shirley |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 15 November 1927 Motueka, Tasman District, New Zealand |

| Died | 31 October 1995 (aged 67) Nelson, New Zealand |

| Political party | Labour |

| Spouse(s) | Glen Elna Reeves (m. 1951) |

| Children | 5 |

| Alma mater | University of Canterbury |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | New Zealand Army |

| Years of service | 1956-61 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | Malayan Emergency |

Rowling was a lecturer in economics when he entered politics; he became a Member of Parliament in the 1962 Buller by-election. He was serving as Minister of Finance (1972–1974) when he was appointed Prime Minister following the death of the highly popular Norman Kirk. His Labour government's effort to retrieve the economy ended with an upset victory by the National Party in November 1975. Rowling continued to lead the Labour Party but lost two more general elections. Upon retiring from the party's leadership in 1983, he was knighted. He served as Ambassador to the United States from 1985 to 1988.

Early life

Rowling was born in a country suburb of Mariri neighbouring the town of Motueka, near Nelson. He was a member of a long-established farming family. He was educated at Nelson College and the University of Canterbury, gaining a degree in economics. He also attended the Christchurch College of Education (currently, University of Canterbury), qualifying as a teacher. After completing his education, Rowling taught at several schools around the country, including at Motueka, Christchurch, Waverley and in Northland. In 1958, Rowling left teaching and joined the New Zealand Army, becoming Assistant Director of Army Education. He spent a short amount of time serving abroad in Malaysia and Singapore, a deployment connected with the Malayan Emergency.[1]

Member of Parliament

| New Zealand Parliament | ||||

| Years | Term | Electorate | Party | |

| 1962–1963 | 33rd | Buller | Labour | |

| 1963–1966 | 34th | Buller | Labour | |

| 1966–1969 | 35th | Buller | Labour | |

| 1969–1972 | 36th | Buller | Labour | |

| 1972–1975 | 37th | Tasman | Labour | |

| 1975–1978 | 38th | Tasman | Labour | |

| 1978–1981 | 39th | Tasman | Labour | |

| 1981–1984 | 40th | Tasman | Labour | |

In the 1960 election, Rowling was selected as the Labour Party's candidate for the Fendalton electorate in Christchurch. Fendalton was regarded as a safe National seat, and Rowling was defeated by the National Party's Harry Lake (who was appointed Minister of Finance in the new National government). Two years later, however, Rowling successfully contested the by-election for Buller, which had been caused by the death of prominent Labour MP Jerry Skinner. Rowling, with a farming background, became Labour's spokesperson on Agriculture and Lands, portfolios previously held by Skinner.[2] Rowling was to hold the Buller seat until the election of 1972, when the seat was dissolved – Rowling then contested successfully the new seat of Tasman, which he did travelling up and down the electorate by Commer campervan, which he lived in for the time.[3]

Not long after entering parliament Rowling began to rise through Labour's internal hierarchy. At the 1966, 1967 and 1968 party conferences Rowling stood for the vice-presidency of the Labour Party, but was narrowly defeated by Henry May on each occasion, however he managed to defeat May in 1969.[4] The following year he was elevated to party presidency. He was the first person to be elected to their first term as president unopposed in Labour history.[5] While Labour was in opposition Rowling was spokesperson for several portfolios including Overseas Trade, Marketing, Broadcasting, Mines, Planning Development and natural resources.[6]

In the lead up to the 1972 election Labour leader Norman Kirk tried to persuade Rowling to transfer from the more marginal Tasman seat to the safe Christchurch seat of Avon. Kirk feared Rowling (by then party president) might lose his seat and did not want to lose his economics expertise. Rowling refused on the grounds that such a self interested move would not be befitting of a party president.[7]

Minister of Finance

When the Labour Party won power under Norman Kirk in the 1972 election, Rowling was appointed Minister of Finance. This could be seen as a considerable promotion for someone without prior ministerial experience. The Labour government enjoyed a record budget surplus in its first year and revalued the currency accordingly. However, the slowing global economy, an unprecedented rise in oil prices and a rapid rise in government expenditure led to soaring inflation by 1974.[8]

Rowling's term as Minister of Finance was somewhat turbulent; from late in 1973, a series of externally generated crises, of which the 'oil shocks' were the most serious, destabilised the New Zealand economy. These added to other problems, such as growing overseas debt and falling export prices. A major financial policy during Rowling's tenure was a comprehensive superannuation scheme.[9]

Prime Minister

When Norman Kirk died unexpectedly in 1974, Hugh Watt, his deputy, served as acting prime minister for several days while the Labour Party caucus chose a new leader. Rowling emerged as the front-runner to replace Kirk. However, the party's National Executive and the Federation of Labour preferred Watt.[10]

Rowling was officially confirmed as party leader and 30th Prime Minister on 6 September 1974.[11] In the cabinet reshuffle following Kirk's death, Rowling took the foreign affairs portfolio.[12] He was appointed to the Privy Council.[13] Rowling had the option of replacing Kirk in the safe Labour seat of Sydenham but chose to remain in his (more marginal) home electorate of Tasman.[14] Rowling considered the idea of holding a snap election under the guise of seeking a personal mandate for himself as Premier. However he was dissuaded from doing so to avoid looking opportunistic and due to Labour having trouble fundraising.[15]

Unlike the pro-life Kirk, Rowling was pro-choice. In 1974, he set up a commission to inquire into contraception, sterilisation and abortion. It issued a report in 1977, with recommendations that were incorporated into the Contraception, Sterilisation, and Abortion Act 1977.[16]

Although Rowling also served as Minister of Foreign Affairs, the Labour Government concentrated primarily on domestic affairs. While Rowling's deputy Bob Tizard had replaced him as Minister of Finance, the seriousness of the economic downturn required the Prime Minister's attention. The Government defended heavy overseas borrowing as necessary to protect jobs. In August 1975, the New Zealand dollar was devalued by 15%.[17]

1975 general election

During the 1975 election campaign, Rowling was attacked by the Opposition led by Robert Muldoon, and was generally characterised as being weak and ineffective. Rowling supporters responded with a "Citizens for Rowling" campaign which enlisted high-profile New Zealanders such as Sir Edmund Hillary to praise Rowling's low-key consultative approach. The campaign was labelled as being elitist, and was generally regarded as having backfired on Rowling.[18] The November election was a major defeat for the Labour Party, and Rowling was unable to retain the premiership.

Leader of the Opposition

During the late 1970s, Rowling alienated some Māori after removing Matiu Rata, the party's experienced and well-regarded Māori Affairs spokesman, from the Opposition front bench.[19] Earlier, Rowling had replaced Rata with himself as convenor of Labour's Māori Affairs Committee. Rata complained about the insensitivity of Labour's Māori policy and went on to form his own Māori rights party, Mana Motuhake.[20]

Rowling's approach to the Moyle and O'Brien 'affairs' was regarded as heavy-handed and unnecessary in many circles. In regards to the 'Moyle affair', in which Labour MP Colin Moyle was accused of having a homosexual affair, "it was Rowling who insisted that his close friend, Colin Moyle, must resign".[21] Large numbers protested at the 1977 Labour Party Conference; many in the LGBT community never forgave him.[22]

Throughout 1980, Labour's poll rating steadily declined eventually reaching the point where they were barely ahead of the Social Credit Party (a minor party). In response to this he was subjected to a leadership challenge at the end of the year. Rowling narrowly survived by one vote (his own). He was visibly angered by the challenge, calling his challengers (known as the Fish and Chip Brigade) 'nakedly ambitious rats' to the press, a comment which he refused to retract.[23]

Rowling, however, managed to retain the party leadership, and gradually managed to improve public perceptions of him. In the 1978 and 1981 elections, Labour actually secured more votes than the National Party but failed to gain a majority of seats. Rowling claimed a moral victory on both occasions.[24]

While Rowling had largely managed to undo his negative image, many people in the Labour Party nevertheless believed that it was time for a change. In 1983 Rowling was replaced as leader by the charismatic David Lange, who went on to defeat Muldoon in the 1984 election. After relinquishing the leadership he remained on the front bench as Shadow Minister of Foreign Affairs.[25] Rowling retired from parliament at the 1984 election.

Later life and death

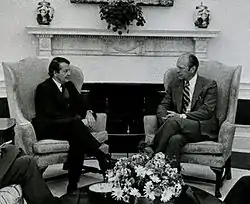

After leaving politics, Rowling was appointed by Lange as Ambassador to the United States, serving from 1985 to 1988. He held that position when the issue of nuclear weapons and ANZUS flared up between the United States and New Zealand, and he travelled extensively across the country explaining the policy.[26]

Exasperated at Labour's Rogernomics economic platform initiated by his successor, David Lange, Rowling eventually let his party membership lapse, expressing dismay at policies undertaken by both the Fourth Labour and Fourth National governments. Rowling later became highly involved in a number of community organisations and trusts. He also played a prominent role at the Museum of New Zealand, and is considered to have been the "driving force" behind the eventual establishment of Te Papa despite drastic public spending cutbacks.[1][27]

Rowling died of cancer in Nelson on 31 October 1995.[26]

Personal life

Rowling married Glen Reeves in 1951. The couple lost their second child when she was five months old in 1957; another daughter, Kim, committed suicide at the age of 18.[26] Rowling was a practising Anglican.[1]

Honours and awards

In the 1983 Queen's Birthday Honours, Rowling was appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George.[28] He was conferred an honorary law doctorate by the University of Canterbury in 1987,[29] and he was honoured by the Netherlands as a Commander in the Orde van Oranje-Nassau.[26]

In the 1988 Queen's Birthday Honours, Glen, Lady Rowling, was appointed a Companion of the Queen's Service Order for community service.[30]

Notes

- Henderson, John. "Rowling, Wallace Edward". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- Henderson 1981, pp. 74-5.

- Henderson 1981, p. 84.

- "Clear Victory as Labour President". The Evening Post. 22 April 1969. p. 14.

- "First Maori Elected to High Office in Labour Party Vote". The Evening Post. 5 May 1970. p. 8.

- Grant 2014, pp. 466–7.

- Grant 2014, p. 196.

- Aimer, Peter (1 June 2015). "Labour Party – Second and third Labour governments". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- Henderson, John (2010). "Rowling, Wallace Edward – Finance minister". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- "Solid weight for Watt but Rowling in?". Auckland Star. 5 September 1974. p. 1.

- "Prime Minister Appointed" (6 September 1974) 87 New Zealand Gazette 1899.

- "Ministers Appointed" (10 September 1974) 88 New Zealand Gazette 1901.

- "Special Honours List" (26 September 1974) 93 New Zealand Gazette 2047.

- Grant 2014, pp. 420.

- Henderson 1981, p. 135.

- Bryder, Linda (2014). The Rise and Fall of National Women's Hospital: A History. Auckland University Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-1-77558-723-1.

- Henderson, John (2010). "Rowling, Wallace Edward – Prime minister". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- Henderson 1981, pp. 136-7.

- "Mr Rata Not In Labour Line-up". The New Zealand Herald. 8 December 1978. p. 1.

- Henderson 1981, p. 14.

- Henderson 1981, pp. 165-6.

- see Henderson, p. 167 for more on Gerald O'Brien and the O'Brien 'affair'

- Bassett 2008, p. 57.

- Henderson, John (2010). "Rowling, Wallace Edward – Opposition and after". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- Bassett 2008, pp. 81–83.

- OBITUARY: Sir Wallace Rowling, The Independent, 1 November 1995.

- "Rowling, Wallace Edward". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. 2010. p. 1.

- "No. 49376". The London Gazette (3rd supplement). 11 June 1983. p. 33.

- "Honorary Graduates" (PDF). University of Canterbury. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- "No. 51367". The London Gazette (3rd supplement). 11 June 1988. p. 34.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bill Rowling. |

- Bassett, Michael (2008). Working with David: Inside the Lange Cabinet. Auckland: Hodder Moa. ISBN 978-1-86971-094-1.

- Grant, David (2014). The Mighty Totara: The life and times of Norman Kirk. Auckland: Random House. ISBN 9781775535799.

- Henderson, John (1981). Rowling: The Man and the Myth. Auckland: Fraser Books. ISBN 0-908620-03-9.

| New Zealand Parliament | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Jerry Skinner |

Member of Parliament for Buller 1962–1972 |

Constituency abolished |

| New constituency | Member of Parliament for Tasman 1972–1984 |

Succeeded by Ken Shirley |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Norman Kirk |

Prime Minister of New Zealand 1974–1975 |

Succeeded by Robert Muldoon |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs 1974–1975 |

Succeeded by Brian Talboys | |

| Preceded by Robert Muldoon |

Minister of Finance 1972–1974 |

Succeeded by Bob Tizard |

| Minister of Statistics 1972–1974 |

Succeeded by Mick Connelly | |

| Leader of the Opposition 1975–1982 |

Succeeded by David Lange | |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Norman Douglas |

President of the Labour Party 1970–1973 |

Succeeded by Charles Bennett |

| Preceded by Norman Kirk |

Leader of the Labour Party 1974–1983 |

Succeeded by David Lange |

| Diplomatic posts | ||

| Preceded by Lance Adams-Schneider |

Ambassador to the United States 1985–1988 |

Succeeded by Tim Francis |