Black school

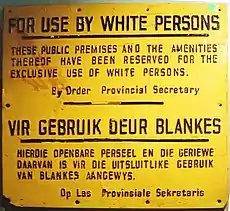

Black schools, also referred to as "colored" schools, were racially segregated schools in the United States that originated after the American Civil War and Reconstruction era. The phenomenon began in the late 1860s during Reconstruction era when Southern states under biracial Republican governments created public schools for ex-slaves. They were typically segregated. After 1877, conservative whites took control across the South. They continued the black schools, but at a much lower funding rate than white schools.

| Part of a series on |

| African Americans |

|---|

|

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Racial segregation |

|---|

|

| Segregation by region |

|

| Similar practices by region |

History

After the Civil War there were only a handful of schools open to blacks, such as the African Free School in New York and the Abiel Smith School in Boston. Individuals and churches, especially the Quakers, sometimes provided instruction. The proposal to set up a "colored" college in New Haven produced a violent reaction, and the project was abandoned. Schools in which black and white children studied together were destroyed by mobs in Connecticut and New Hampshire. Few African Americans in the South received any education at all until after the Civil War. Slaves had been prohibited from being educated, and there was generally no public school system for white children, either. The planter elite paid for private education for its children. Legislatures of Republican freedmen and whites established public schools for the first time during the Reconstruction era.

At the beginning of the Reconstruction era, teachers in integrated schools were predominantly white. Black educators and education leadership found that many of these white teachers "...effectively convinced black students that they were inferior." This led to distrust of the structure of public education at that time.[1][2] Because of racism directed at Black students, public schools became segregated throughout the south during Reconstruction and until the 1950s. New Orleans was a partial exception: its schools were usually integrated during Reconstruction.[3]

After the white Democrats regained power in Southern states in the 1870s, during the next two decades they imposed Jim Crow laws mandating segregation. They disfranchised most blacks and many poor whites through poll taxes and literacy tests. Services for black schools (and any black institution) routinely received far less financial support than white schools. In addition, the South was extremely poor for years in the aftermath of the war, its infrastructure destroyed, and dependent on an agricultural economy despite falling cotton prices. Into the 20th century, black schools had second-hand books and buildings (see Station One School),and teachers were paid less and had larger classes.[4] In Washington, DC, however, because public school teachers were federal employees, African-American and Caucasian teachers were paid the same.

The Virginia Constitution of 1870 mandated a system of public education for the first time, but the newly established schools were operated on a segregated basis. In these early schools, which were mostly rural, as was characteristic of the South, classes were most often taught by a single teacher, who taught all subjects, ages, and grades. Chronic underfunding led to constantly over-populated schools, despite the relatively low percentage of African-American students in schools overall. In 1900 the average black school in Virginia had 37 percent more pupils in attendance than the average white school. This discrimination continued for several years, as demonstrated by the fact that in 1937–38, in Halifax County, Virginia, the total value of white school property was $561,262, contrasted to only $176,881 for the county's black schools.[4]

In the 1930s the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People launched a national campaign to achieve equal schools within the "separate but equal" framework of the U.S. Supreme Court's 1896 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson. White hostility towards this campaign kept black schools from necessary resources. According to Rethinking Schools magazine, "Over the first three decades of the 20th century, the funding gap between black and white schools in the South increasingly widened. NAACP studies of unequal expenditures in the mid-to-late 1920s found that Georgia spent $4.59 per year on each African-American child as opposed to $36.29 on each white child. A study by Doxey Wilkerson at the end of the 1930s found that only 19 percent of 14- to 17-year-old African Americans were enrolled in high school."[5] The NAACP won several victories with this campaign, particularly around salary equalization.

Rosenwald Schools

Julius Rosenwald was a U.S. clothier, manufacturer, business executive, and philanthropist. A part-owner and leader of Sears, Roebuck and Company, he was responsible for establishing the Rosenwald Fund. After meeting Booker T. Washington in 1911, Rosenwald created his fund to improve the education of southern blacks by building schools, mostly in rural areas. More than 5,300 were built in the South by the time of Rosenwald's death in 1932. He created a system of requiring matching public funds and interracial community cooperation for maintenance and operation of schools. Black communities essentially taxed themselves twice to raise money to support new schools, often donating land and labor to get them built.[6][7]

With increasing urbanization, Rosenwald schools in many rural areas were abandoned. Some have been converted to community centers and in more urban areas, maintained or renovated as schools. In modern times the National Trust for Historic Preservation has called Rosenwald Schools as worthy of preservation as "beacons of African American education".[8] By 2009 many communities restored Rosenwald schools.[9]

Citizenship Schools

Septima Clark was an American educator, civil rights activist, and the creator of citizenship schools in 1957.[10] Clark's project initially developed from secret literacy courses she held for African American adults in the Deep South. Citizenship schools helped Black Southerners push for the right to vote, as well as create activists and leaders for the Civil Rights Movement, using a curriculum that instilled self-pride, cultural-pride, literacy, and a sense of one's citizenship rights. The citizenship school project trained over 10,000 citizenship school teachers who led over 800 citizenship schools throughout the South that was responsible for registering approximately 700,000 African Americans to vote.[11]

Freedom Schools

An activist of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in 1964, Charles Cobb, proposed that the organization sponsor a network of Freedom Schools. Originally Freedom Schools were organized to achieve social, political, and economic equality through teaching African American students to be social change agents for the Civil Rights Movement; Black educators and activists later utilized the schools to provide schooling in areas where black public schools were closed in reaction to the Brown v. Board of Education ruling. More than 40 of these free schools existed by the end of the summer in 1964 serving close to 3,000 students.[12]

Desegregation

Public schools were technically desegregated in the United States in 1954 by the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown vs Board of Education. Some schools, such as the Baltimore Polytechnic Institute, were forced into a limited form of desegregation before that; with the Baltimore City Public School System voting to desegregate the prestigious advanced placement programme in 1952. However, many were still de facto segregated due to inequality in housing and patterns of racial segregation in neighborhoods. President Dwight Eisenhower enforced the Supreme Court's decision by sending US Army troops to Little Rock, Arkansas to protect the "Little Rock Nine" students' entry to school in 1957, thus setting a precedent for the Executive Branch to enforce Supreme Court rulings related to racial integration. He was the first president since Reconstruction to send Federal troops into the South to protect the rights of African Americans.[13]

Busing

In the 1971 Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education ruling, the Supreme Court allowed the federal government to force mandatory busing on Charlotte, North Carolina and other cities nationwide in order to affect student assignment based on race and to attempt to further integrate schools. This was meant to combat patterns of de facto segregation that had developed in northern as well as southern cities.[14] 1974's Milliken v. Bradley decision placed a limitation on Swann when they ruled that students could only be bused across district lines when evidence existed of de jure segregation across multiple school districts. In the 1970s and 1980s, under federal court supervision, many school districts implemented mandatory busing plans within their districts. Busing was controversial because it took students out of their own neighborhoods and further away from their parents' supervision and support. Even young students sometimes had lengthy bus rides each day. Districts also experimented with creating incentives, for instance, magnet schools to attract different students voluntarily.

Re-segregation

According to the Civil Rights Project at Harvard University, the desegregation of U.S. public schools peaked in 1988; since then, schools have become more segregated because of changes in demographic residential patterns with continuing growth in suburbs and new communities. Jonathan Kozol has found that as of 2005, the proportion of Black students at majority-white schools was at "a level lower than in any year since 1968."[15] Changing population patterns, with dramatically increased growth in the South and Southwest, decreases in old industrial cities, and much increased immigration of new ethnic groups, have altered school populations in many areas.

Black school districts continue to try various programs to improve student and school performance, including magnet schools and special programs related to the economic standing of families. Omaha proposed incorporating some suburban districts within city limits to enlarge its school-system catchment area. It wanted to create a "one tax, one school" system that would also allow it to create magnet programs to increase diversity in now predominately white schools. Ernest Chambers, a 34-year-serving African-American state senator from North Omaha, Nebraska, believed a different solution was needed. Some observers said that in practical terms, public schools in Omaha had been re-segregated since the end of busing in 1999.[16]

In 2006, Chambers offered an amendment to the Omaha school reform bill in the Nebraska State Legislature which would provide for creation of three school districts in Omaha according to current racial demographics: black, white and Hispanic, with local community control of each district. He believed this would give the African-American community the chance to control a district in which their children were the majority. Chambers’ amendment was controversial. Opponents to the measure described it as "state-sponsored segregation".[17]

The authors of a 2003 Harvard study on re-segregation believe current trends in the South of white teachers leaving predominately black schools is an inevitable result of federal court decisions limiting former methods of civil rights-era protections, such as busing and affirmative action in school admissions. Teachers and principals cite other issues, such as economic and cultural barriers in schools with high rates of poverty, as well as teachers' choices to work closer to home or in higher-performing schools. In some areas black teachers are also leaving the profession, resulting in teacher shortages.[18]

See also

- United States school desegregation case law (category)

- African American culture

- African American

- Timeline of the civil rights movement

- The Shame of the Nation: The Restoration of Apartheid Schooling in America

References

- Betty Jamerson Reed (2011). School Segregation in Western North Carolina: A History, 1860s-1970s. McFarland. p. 21. ISBN 9780786487080.

- Nell Irvin Painter (1992). Exodusters: Black Migration to Kansas After Reconstruction. pp. 49–51. ISBN 9780393352511.

- . Harlan, "Desegregation in New Orleans Public Schools During Reconstruction." American Historical Review 67#3 (1962): 663-675. in JSTOR

- "Beginnings of black education" Archived 2009-07-21 at the Wayback Machine, The Civil Rights Movement in Virginia. Virginia Historical Society. Retrieved 4/12/09.

- Lowe, R. "The Strange History of School Desegregation", Rethinking Schools. Volume 18, No. 3, Spring 2004. Retrieved 4/12/09.

- Brooker, Russell. "The Rosenwald Schools: An Impressive Legacy Of Black-Jewish Collaboration For Negro Education". America's Black Holocaust Museum. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- "The Rosenwald School Program". searsarchives.com. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- "The Rosenwald Schools Initiative". National Trust for Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on August 2, 2008. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- Eckholm, Eric (January 14, 2010). "Black Schools Restored as Landmarks". The New York Times. Retrieved January 15, 2010.

- Charron, Katherine Mellen (2009). Freedom's Teacher: The Life of Septima Clark. The University of North Carolina Press.

- Brown-Nagin, Tomiko (1999). "The Transformation of a Social Movement into Law? the SCLC and NAACP's campaigns for civil rights reconsidered in the light of the educational activism of Septima Clark". Women's History Review. Taylor & Francis. 8 (1): 81–137. doi:10.1080/09612029900200193.

- Hartford, Bruce (2014). "Mississippi Freedom Summer, 1964" (PDF). Civil Rights Movement Archive. pp. 51–56. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- "Mob Rule Cannot Be Allowed to Override the Decisions of Our Courts": President Dwight D. Eisenhower's 1957 Address on Little Rock, Arkansas." George Mason University. Retrieved 4/12/09.

- Frum, D. (2000) How We Got Here: The 1970s, New York, NY: Basic Books. pp. 252-264.

- Kozol, J. "Overcoming Apartheid", The Nation, December 19, 2005. p. 26

- Johnson, T. A. (2009-02-03) "African American Administration of Predominately Black Schools: Segregation or Emancipation in Omaha, Nebraska." Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association for the Study of African-American Life and History in Charlotte, NC.

- "Law to Segregate Omaha Schools Divides Nebraska", The New York Times. April 15, 2006. Retrieved April 12, 2009.

- Jonnson, P. (January 21, 2003) "White teachers flee black schools", The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 4/12/09.

Further reading

- Alexander, Roberta Sue. "Hostility and hope: Black education in North Carolina during presidential Reconstruction, 1865-1867." North Carolina Historical Review 53.2 (1976): 113–132. online

- Allen, Quaylan, and Kimberly White-Smith. ""That’s why I say stay in school": Black mothers’ parental involvement, cultural wealth, and exclusion in their son's schooling." Urban Education 53.3 (2018): 409-435. online

- Allen, Walter R., et al. "From Bakke to Fisher: African American Students in US Higher Education over Forty Years." RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 4.6 (2018): 41–72. online

- Anderson, James D. "Northern foundations and the shaping of southern black rural education, 1902–1935." History of Education Quarterly 18.4 (1978): 371–396. online

- Anderson, James D. The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860-1935 (1988); the standard scholarly study. online edition

- Burton, Vernon. "Race and Reconstruction: Edgefield County, South Carolina." Journal of Social History (1978): 31–56. online

- Butchart, Ronald E. Northern schools, southern Blacks, and Reconstruction: Freedmen's education, 1862-1875 (Praeger, 1980).

- Butchart, Ronald E. "Black hope, white power: emancipation, reconstruction and the legacy of unequal schooling in the US South, 1861–1880." Paedagogica historica 46.1-2 (2010): 33–50.

- Coats, Linda T. "The Way We Learned: African American Students' Memories of Schooling in the Segregated South." Journal of Negro Education 79.1 (2010). online

- Crouch, Barry A. "Black Education in Civil War and Reconstruction Louisiana: George T. Ruby, the Army, and the Freedmen's Bureau." Louisiana History 38.3 (1997): 287–308. online

- Davis, Alicia, and Greg Wiggan. "Black Education and the Great Migration." Black History Bulletin 81.2 (2018): 12–16. [ online]

- Fairclough, Adam. "The costs of Brown: Black teachers and school integration." Journal of American History 91.1 (2004): 43–55. online

- Harlan, Louis R. "Desegregation in New Orleans public schools during reconstruction." American Historical Review 67.3 (1962): 663–675. online

- Horsford, Sonya Douglass. "Black superintendents on educating Black students in separate and unequal contexts." The Urban Review 42.1 (2010): 58–79. online

- Kelly, Hilton. "What Jim Crow’s teachers could do: Educational capital and teachers’ work in under-resourced schools." The Urban Review 42.4 (2010): 329-350. online

- Lewis, Ronald, and Phyllis M. Belt-Beyan. The Emergence of African American Literacy Traditions: Family and Community Efforts in the Nineteenth Century (2004) online edition

- Lincoln, E.A. White Teachers, Black Schools, and the Inner City: Some Impressions and Concerns. (1975)

- Moneyhon, Carl H. "Public Education and Texas Reconstruction Politics, 1871-1874." Southwestern Historical Quarterly 92.3 (1989): 393–416. online

- Rosen, F. Bruce. "The influence of the Peabody Fund on education in Reconstruction Florida." Florida Historical Quarterly 55.3 (1977): 310–320. online

- Span, Christopher M. From Cotton Field to Schoolhouse: African American Education in Mississippi, 1862-1875 (2009) online edition

- Taylor, Kay Ann. "Mary S. Peake and Charlotte L. Forten: Black teachers during the Civil War and Reconstruction." Journal of Negro Education (2005): 124–137. online