Congressional Black Caucus

The Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) is a caucus made up of most African-American members of the United States Congress. Representative Karen Bass from California chaired the caucus from 2019 to 2021, when Representative Joyce Beatty from Ohio became its chair. [4][5][6][7] [8] As of 2020, all members of the caucus are part of the Democratic Party.

History

Founding

The predecessor to the caucus was founded in January 1969 as the Democratic Select Committee by a group of black members of the House of Representatives, including Shirley Chisholm of New York, Louis Stokes of Ohio and William L. Clay of Missouri. Black representatives had begun to enter the House in increasing numbers during the 1960s, and they had a desire for a formal organization.[2] Further, Congressional redistricting in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement resulted in the number of black Congressmembers from nine to thirteen.[2] The first chairman, Charles Diggs, served from 1969 to 1971.

This organization was renamed the Congressional Black Caucus in February 1971 on the motion of Charles B. Rangel of New York. The thirteen founding members of the caucus were Shirley Chisholm, Bill Clay, George W. Collins, John Conyers, Ron Dellums, Charles Diggs, Augustus F. Hawkins, Ralph Metcalfe, Parren Mitchell, Robert N.C. Nix, Sr., Charles Rangel, Louis Stokes, and Washington, D.C,. delegate Walter E. Fauntroy.[9] Chisholm referred to the group as "unbought and unbossed".[10] Five founding members of the CBC were also members of Prince Hall Freemasonry, an African-American branch of Freemasonry that became involved in civil rights; Stokes, Conyers, Rangel, Hawkins and Metcalfe.

President Richard Nixon refused to meet with the newly-formed group, and so the CBC chose to boycott the 1971 State of the Union address, leading to their first joint press coverage.[2] On March 25, 1971, Nixon finally met with the CBC, who presented him with a 32-page document including "recommendations to eradicate racism, provide quality housing for black families, and promote the full engagement of blacks in government".[2] All the members of the caucus were included on the master list of Nixon political opponents.

On June 5, 1972, shortly before the 1972 Democratic National Convention would nominate George McGovern for president, the CBC wrote and released two documents: the Black Declaration of Independence and the Black Bill of Rights.[10] Louis Stokes read a preamble and both documents into the record of the House of Representatives.[2] The Black Bill of Rights includes sections on jobs and the economy, foreign policy, education, housing, public health, minority enterprise, drugs, prison reform, black representation in government, civil rights, voting rights in the District of Columbia, and the military.[11] These documents were inspired by the National Black Political Convention and its own manifesto, The Gary Declaration: Black Politics at the Crossroads[12] (also called the Black Agenda).

TransAfrica and Free South Africa Movement

In 1977, the organization was involved in the founding of TransAfrica, an education and advocacy affiliate that was formed to act as a resource on information on the African continent and its Diaspora.[13] They worked closely with this organization to start the national anti-apartheid movement in the US, Free South Africa Movement (characterized by sit-ins, student protests, it became the longest lasting civil disobedience movement in U.S history) and to devise the legislative strategy for the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986 that was subsequently passed over Ronald Reagan's veto. The organization continues to be active today and works on other campaigns.[13][14]

Funding

In late 1994, after Republicans attained a majority in the House, the House passed House Resolution 6 on January 4, 1995, which prohibited “the establishment or continuation of any legislative service organization..."[15] This decision was aimed at 28 organizations, which received taxpayer funding and occupied offices at the Capitol, including the CBC. Then-chairman Kweisi Mfume protested the decision. The CBC reconstituted as a Congressional Member Organization.[16]

Events

The caucus is sometimes invited to the White House to meet with the president.[17] It requests such a meeting at the beginning of each Congress.[17]

During the 2020 George Floyd protests, the CBC provided House members with stoles made from kente to be worn for an 8:46-long moment of silence before introducing the Justice in Policing Act of 2020.[18]

Goals

The caucus describes its goals as "positively influencing the course of events pertinent to African Americans and others of similar experience and situation", and "achieving greater equity for persons of African descent in the design and content of domestic and international programs and services."

The CBC encapsulates these goals in the following priorities: closing the achievement and opportunity gaps in education, assuring quality health care for every American, focusing on employment and economic security, ensuring justice for all, retirement security for all Americans, increasing welfare funds, and increasing equity in foreign policy.[19]

Representative Eddie Bernice Johnson (D–TX), has said:

The Congressional Black Caucus is one of the world's most esteemed bodies, with a history of positive activism unparalleled in our nation's history. Whether the issue is popular or unpopular, simple or complex, the CBC has fought for thirty years to protect the fundamentals of democracy. Its impact is recognized throughout the world. The Congressional Black Caucus is probably the closest group of legislators on the Hill. We work together almost incessantly, we are friends and, more importantly, a family of freedom fighters. Our diversity makes us stronger, and the expertise of all of our members has helped us be effective beyond our numbers.

Mark Anthony Neal, a professor of African-American studies and popular culture at Duke University, wrote a column in late 2008 that the Congressional Black Caucus and other African-American-centered organizations are still needed, and should take advantage of "the political will that Obama's campaign has generated."[20]

Membership

- Shirley Chisholm

(from New York's 12th district) - Bill Clay

(from Missouri's 1st district) - George W. Collins

(from Illinois's 6th district) - John Conyers

(from Michigan's 1st district) - Ron Dellums

(from California's 7th district) - Charles Diggs

(from Michigan's 13th district) - Walter Fauntroy

(from District of Columbia's at-large district) - Augustus F. Hawkins

(from California's 21st district) - Ralph Metcalfe

(from Illinois's 1st district) - Parren Mitchell

(from Maryland's 7th district) - Robert N.C. Nix Sr.

(from Pennsylvania's 2nd district) - Charles Rangel

(from New York's 18th district) - Louis Stokes

(from Ohio's 21st district)

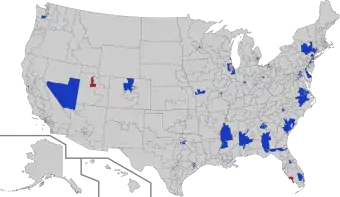

The caucus has grown steadily as more black members have been elected. At its formal founding in 1971, the caucus had thirteen members.[2] As of 2019, it had 55 members, including two who are non-voting members of the House, representing the District of Columbia and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Senate members

As of 2019, there have been eight black senators since the caucus's founding. The six black U.S. senators, all Democrats, who are or have been members of the Congressional Black Caucus are Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey, elected in 2013, and Senator Kamala Harris of California, elected in 2016, both currently serving; former senators Carol Moseley Braun (1993–1999), Barack Obama (2005–2008), and Roland Burris (2008–2010), all of Illinois; and former senator Mo Cowan (2013) of Massachusetts. Burris was appointed by Illinois governor Rod Blagojevich in December 2008 to fill Obama's seat for the remaining two years of his Senate term after Obama was elected president of the United States. Cowan was appointed to temporarily serve until a special election after John Kerry vacated his Senate seat to become U.S. secretary of state.

Senator Edward Brooke, a Republican who represented Massachusetts in the 1960s and 1970s, was not a member of the CBC. In 2013, Senator Tim Scott, Republican of South Carolina, also chose not to join the CBC after being appointed to fill Jim DeMint's Senate seat.

Black Republicans in the CBC

The caucus is officially non-partisan; but, in practice, the vast majority of blacks elected to Congress since the CBC's founding have been Democrats. Ten black Republicans have been elected to Congress since the caucus was founded in 1971: Senator Edward Brooke of Massachusetts (1967–1979), Delegate Melvin H. Evans of the Virgin Islands (1979–1981), Representative Gary Franks of Connecticut (1991–1997), Representative J. C. Watts of Oklahoma (1995–2003), Representative Allen West of Florida (2011–2013), Senator Tim Scott of South Carolina (2013–present), Representative Will Hurd of Texas (2015–2021), Representative Mia Love of Utah (2015–2019), Representative Byron Donalds of Florida, and Representative Burgess Owens of Utah (2021-present). Of these ten, only Evans, Franks, West, and Love joined the CBC; currently, the caucus includes no Republicans.

Edward Brooke was the only serving black U.S. senator when the CBC was founded in 1971, but he never joined the group and often clashed with its leaders.[21] In 1979 Melvin H. Evans, a non-voting delegate from the Virgin Islands, became the first Republican member in the group's history. Gary Franks was the first Republican voting congressman to join in 1991, though he was at times excluded from CBC strategy sessions, skipped meetings, and threatened to quit the caucus.[22] J. C. Watts did not join the CBC when he entered Congress in 1995, and after Franks left Congress in 1997, no Republicans joined the CBC for fourteen years until Allen West joined the caucus in 2011, though fellow freshman congressman Tim Scott declined to join.[23] After West was defeated for re-election, the CBC became a Democrat-only caucus once again in 2013.[24]

In 2014, two black Republicans were elected to the House. Upon taking office, Will Hurd from Texas declined to join the caucus, while Mia Love from Utah, the first black Republican congresswoman, joined.[25]

Non-black membership

All past and present members of the caucus have been African-American. In 2006, while running for Congress in a Tennessee district which is 60% black, Steve Cohen, who is white and Jewish, pledged to apply for membership in order to represent his constituents. However, after his election, his application was refused.[26] Although the bylaws of the caucus do not make race a prerequisite for membership, former and current members of the caucus agreed that the group should remain "exclusively black". In response to the decision, Cohen referred to his campaign promise as "a social faux pas" because "It's their caucus and they do things their way. You don't force your way in. You need to be invited."[26]

Representative Lacy Clay, a Democrat from Missouri and the son of Representative Bill Clay, a co-founder of the caucus, said: "Mr. Cohen asked for admission, and he got his answer. He is white and the caucus is black. It is time to move on. We have racial policies to pursue and we are pursuing them, as Mr. Cohen has learned. It is an unwritten rule. It is understood." Clay also issued the following statement:

Quite simply, Representative Cohen will have to accept what the rest of the country will have to accept—there has been an unofficial Congressional White Caucus for over 200 years, and now it is our turn to say who can join 'the club.' He does not, and cannot, meet the membership criteria unless he can change his skin color. Primarily, we are concerned with the needs and concerns of the black population, and we will not allow white America to infringe on those objectives.[27]

Later the same week, Representative Tom Tancredo, a Republican from Colorado, objected to the continued existence of the CBC as well as the Democratic Congressional Hispanic Caucus and the Republican Congressional Hispanic Conference arguing that "It is utterly hypocritical for Congress to extol the virtues of a color-blind society while officially sanctioning caucuses that are based solely on race. If we are serious about achieving the goal of a colorblind society, Congress should lead by example and end these divisive, race-based caucuses."[28]

Afro-Latino membership

Prior to 2017, no one had attempted to be in both the CBC and the Congressional Hispanic Caucus. In the 2016 House elections, Afro-Dominican State Senator Adriano Espaillat was elected to an open seat after twice trying to unseat CBC founder Charlie Rangel (who also has Puerto Rican ancestry) in the Democratic primary. Espaillat signaled that he wanted to join the CBC as well as the CHC, but it was reported that he was rebuffed, and it was insinuated that the cause was bad blood over the attempted primary challenges of Rangel.[29] In the 2018 elections, Afro-Puerto Rican Democrat Antonio Delgado was elected and joined the CBC, making no public effort to join the CHC as well. In the 2020 elections, Afro-Puerto Rican Democratic candidate Ritchie Torres published an Op-ed claiming that he was prevented from joining both the CBC and CHC as he wished to do,[30] a claim which was denied by then-CBC chair Karen Bass.[31] Torres was successful in his bid for the House; CBC membership for the 117th United States Congress has yet to be announced.

Chairs

The following U.S. representatives have chaired the Congressional Black Caucus:[32]

- 1971–1972: Charles Diggs (MI–13)

- 1972–1974: Louis Stokes (OH–21)

- 1974–1976: Charles Rangel (NY–19)

- 1976–1977: Yvonne Brathwaite Burke (CA–28)

- 1977–1979: Parren Mitchell (MD–7)

- 1979–1981: Cardiss Collins (IL–7)

- 1981–1983: Walter Fauntroy (DC at-large)

- 1983–1985: Julian C. Dixon (CA–28)

- 1985–1987: Mickey Leland (TX–18)

- 1987–1989: Mervyn M. Dymally (CA–31)

- 1989–1991: Ron Dellums (CA–8)

- 1991–1993: Edolphus Towns (NY–11)

- 1993–1995: Kweisi Mfume (MD–7)

- 1995–1997: Donald Payne (NJ–10)

- 1997–1999: Maxine Waters (CA–35)

- 1999–2001: Jim Clyburn (SC–6)

- 2001–2003: Eddie Bernice Johnson (TX–30)

- 2003–2005: Elijah Cummings (MD–7)

- 2005–2007: Mel Watt (NC–12)

- 2007–2009: Carolyn Cheeks Kilpatrick (MI–13)

- 2009–2011: Barbara Lee (CA–9)

- 2011–2013: Emanuel Cleaver (MO–5)

- 2013–2015: Marcia Fudge (OH–11)

- 2015–2017: G. K. Butterfield (NC–1)

- 2017–2019: Cedric Richmond (LA–2)

- 2019–2021: Karen Bass (CA–37)

- 2021–present: Joyce Beatty (OH–3)

Composition during the 116th Congress

Leadership

- Chair Karen Bass (CA-37, D)[4][5]

- First vice-chair Joyce Beatty (OH-3, D)[4][5]

- Second vice-chair Brenda Lawrence (MI-14, D)[4][5]

- Whip Donald McEachin (VA-4, D)[4][5]

- Secretary Hank Johnson (GA-04, D)[4][5]

- Parliamentarian Steven Horsford (NV-4, D)[4][5]

- Member-at-large Yvette Clarke (NY-9, D)

Members

During the 116th Congress (2019–2021), the CBC has 2 U.S. senators, 50 voting U.S. representatives and 2 non-voting delegates as members:[33]

See also

References

- "The History of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC)". United States House of Representatives. Archived from the original on April 27, 2016. Retrieved April 18, 2016.

- Office of the Historian (2008). ""Creation and Evolution of the Congressional Black Caucus," Black Americans in Congress, 1870–2007". History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved April 17, 2016.

- "116th United States Congress". Ballotpedia.

- "Leadership". Congressional Black Caucus. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- "Congressional Black Caucus". Congressional Black Caucus. November 28, 2018.

- "Congressional Black Caucus Chair Cedric Richmond Says Goodbye to Seat as he Prepares to Pass "Chair" to Rep. Karen Bass". January 2, 2019.

- "The Blue Wave Of Black Politicians Gets Sworn In". January 3, 2019.

- "Joyce Beatty elected next chair of Congressional Black Caucus". beatty.house.gov. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- "History". Congressional Black Caucus. Archived from the original on March 27, 2016. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- Taylor, Keeanga-Yamahtta (June 13, 2020). "Opinion: The End of Black Politics". The New York Times. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- 1972 Congressional Record, Vol. 118, Page E19754 (June 5, 1972)

- "Gary Declaration, National Black Political Convention, 1972 | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed". www.blackpast.org. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- "TransAfrica". African Activist Archives. Michigan State University. Retrieved April 17, 2016.

- "Senate Rebukes Reagan". The Courier. October 3, 1986. p. 28. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- "thomas.loc.gov 104th Congress, H.Res.6, Section 222" (PDF).

- Cortés, Carlos E. (2013). "House of Representatives, U.S.". Multicultural America: A Multimedia Encyclopedia. SAGE Publications. p. 1118. ISBN 9781452276267.

- Josephine Hearn (February 13, 2007). "Black Caucus to Make Rare White House Visit". Politico.

- Friedman, Vanessa (June 16, 2020). "The Dress Codes of the Uprising". The New York Times. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- "Priorities of the Congressional Black Caucus for the 109th Congress". U.S. House of Representatives. Archived from the original on December 30, 2005. Retrieved April 17, 2016.

- Jackson, Camille (December 19, 2008). "Hitting the Ground Running". Duke University This Month at Duke. Retrieved February 7, 2009.

- "Brooke, Edward William, III". History, Art & Archives: United States House of Representatives. January 3, 2015. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- Barnes, Fred (March 17, 2011). "Rep. Allen West – and the Congressional Black Caucus". The Weekly Standard. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- Southall, Ashley (January 5, 2011). "Republican Allen West Joins Congressional Black Caucus". The New York Times. Retrieved January 5, 2011.

- Alvarez, Lizette (November 20, 2012). "Republican Concedes House Race in Florida". The New York Times.

- "Congressional Black Caucus Members". Congressional Black Caucus. Archived from the original on January 14, 2015. Retrieved January 26, 2015.

- Hearn, Josephine (January 23, 2007). "Black Caucus: Whites Not Allowed". Politico.com. Retrieved January 23, 2007.

- Ta-Nehisi Coates (August 8, 2008). "Should a white guy get to join the black caucus?". The Atlantic.

- "Tancredo: Abolish black, Hispanic caucuses". NBC News. January 25, 2007. Retrieved April 19, 2009.

- Caygle, Heather (February 3, 2017). "Black Caucus chafes at Latino who wants to join". Politico. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- Torres, Ritchie (July 19, 2020). "I'm Afro-Latino, but I can't join both the black and Hispanic caucuses in Congress. That must change". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- Barrón-López, Laura; Caygle, Heather (July 22, 2020). "CBC head: Nothing is stopping Afro-Latinos from joining both Black, Hispanic caucuses". Politico. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- "Congressional Black Caucus Chairmen and Chairwomen, 1971–Present". Black Americans in Congress. U.S. House of Representatives. Retrieved November 27, 2010.

- "Membership". Congressional Black Caucus. Retrieved March 13, 2018.

Bibliography

- Singh, Robert (1998). The Congressional Black Caucus: Racial Politics in the U.S. Congress. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.