Brent Cross Shopping Centre

Brent Cross Shopping Centre is a large shopping centre in Hendon, north London, owned by Hammerson and Standard Life Aberdeen. Located by the Brent Cross interchange, it opened in 1976 as the UK's first out-of-town shopping centre.[2] Brent Cross attracted 15-16 million shoppers a year as of 2011[3] and has one of the largest incomes per unit area of retail space in the country.[4]

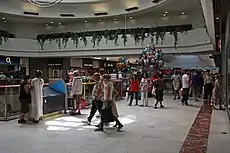

Centre complex as seen (from the John Lewis end) from the parking area | |

| |

| Location | Hendon, London, England |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 51.57687°N 0.21574°W |

| Opening date | 2 March 1976 |

| Owner | Hammerson and Standard Life Aberdeen |

| Architect | BDP |

| Total retail floor area | 910,000 sq ft (85,000 m2) (internal)[1] |

| No. of floors | 2 (3 in Fenwick, John Lewis & M&S) |

| Parking | 8000 |

| Website | brentcross |

History

Brent Cross Shopping Centre was built by Hammerson and opened on 2 March 1976.[5] It was the country's first out-of-town and American-style indoor shopping centre in the country, with its construction taking 19 years to complete at a cost of £20 million.[6] The scheme was strongly supported by the local authority of Barnet, but strongly opposed by local traders in Hendon.[7] The centre started out with 800,000 sq ft (74,320 m2) of retail space[8] on a 52 acres (21 ha) site.[9]

Upon opening, Brent Cross had 75 stores and was open until late every weekday despite the mid-1970s UK recession.[10]

On 14 December 1991, four explosive devices were planted by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA). The bombs were discovered and defused before they could be detonated.[11]

By the 1990s, the centre was facing increasing competition from other large out-of-town shopping centres in the region, such as the Lakeside Shopping Centre. In 1994 work started to extend the centre which was completed by 1996, giving it capacity for 120 stores[10] as well as a new multi-storey car park replacing the older one, adding 2,000 extra spaces. Also the low ceiling inside was replaced by glass to let more natural light in.[9]

On 6 November 2012, six people on three motorbikes entered the shopping centre and smashed in the windows at jewellers Fraser Hart. An estimated £2 million worth of jewellery was stolen.[12]

Brent Cross shopping centre is planned to be extended as a part of the Brent Cross Cricklewood regeneration scheme. The John Lewis and Fenwick Department stores will remain in their current location, Marks & Spencer will move to a new location on the extended site, the bus station will be relocated, and new parks, a "living bridge" across the North Circular Road and a cinema are planned, along with new multi-storey car parks (with the existing surface carparks to be used for the shopping centre extension). Outline planning permission was achieved in 2010, and preparatory site clearance started in early 2018. Construction had been expected to start in 2018,[13] but is now delayed until 2019.[14]

Reception

Upon its recession-era opening in 1976, Brent Cross was praised by the public bringing a bold American-style concept to Britain. A local newspaper called the centre a "fururistic concept", and its features such as the indoor fountain and air conditioning were noted. Richard Hyman, a retail analyst, said that Brent Cross's significance "can't be overstated. Before Brent Cross there was nothing like it."[15]

Brent Cross was unusual at the time in that it was build on an undeveloped site rather than in a traditional town centre. The centre was built on a "concrete island" surrounded by the Brent Cross flyovers and the busy North Circular Road, but the centre's offering inside is what drew customers to it. The New Society magazine wrote about the centre in 1978:[7]

The massive and featureless rectangles of the Brent Cross Shopping Centre... come as no surprise. They are just as hideous as everything else. But step through the doors and here is prettiness and femininity - just as soulless and just as commercialised as the filth outside, but a veritable perfumed nirvana.

Brent Cross quickly became a popular attraction for people in London and the South East, and a blueprint for shopping centres across Europe. Despite its age and dated appearance,[16] it has remained a popular retail centre ever since.[17] It was ranked as London's 5th largest retail centre in 2005, behind the West End, Croydon, Kingston upon Thames and Bromley.[18] In 2013 it was reported that it received 14 million visitors a year.[19] It was ranked the UK's 9th best shopping centre in 2019 by GlobalData.[20]

The original three department stores when Brent Cross opened - Fenwick, John Lewis and Marks & Spencer - remain at the site.[17] The former two have anchored the shopping centre since the beginning.[21]

Transport

The nearest train stations are Brent Cross tube station and Hendon Central tube station on the Northern line. The shopping centre is surrounded by a "concrete jungle" of trunk roads typical from the time it was built.[22] As a result pedestrian access to and from the shopping centre complex has been deemed "hostile" in modern times.[23] As part of the Brent Cross Cricklewood regeneration scheme, a new Brent Cross West Thameslink station will be built and opened in the early 2020s,[24] and the environment will be improved for pedestrians. The Brent Cross bus station is adjacent to the shopping centre and is served by 14 different day bus routes with links throughout North London and to West London, the West End, and Hertfordshire.[25]

In popular culture

The interior of the shopping centre was featured in the 1994 film London by Patrick Keiller.[26] It shows the former large fountain and stained glass on the roof, which were removed in 1996.[27]

The carpark of the shopping centre was used as a filming location for the 1997 James Bond film Tomorrow Never Dies.[28]

The shopping centre was also featured in Ken MacLeod's science-fiction novel The Star Fraction. The action takes place in a balkanized UK, in the middle of the 21st century, and the ruins of the shopping centre are used as a local market for the anarchist enclave of Norlonto ('North London Town').[29]

References

- "Brent Cross Shopping Centre, Brent Cross". Completely Retail. Retrieved 2020-04-27.

- "A brief history of the shopping centre". April 19, 2013 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- Goldfingle2011-02-23T09:13:00+00:00, Gemma. "HMV to close Brent Cross store". Retail Week.

- David. "London's best shopping centres |". Parkgrandlondon.com. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- "View of shopping centre, 1977". London Transport Museum. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 26 November 2017.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Wallop, Harry (1 March 2016). "Brent Cross is now 40-years old. Will shopping centres be here in another 40?" – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- Travers, Tony (2015). London Boroughs at 50. Biteback Publishing. ISBN 978-1849549196.

- "Shopping Centres". Museum of London. Archived from the original on 5 June 2008. Retrieved 26 November 2017.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Jackson, Peter; Rowlands, Michael; Miller, Daniel (2005-09-20). Shopping, Place and Identity - Peter Jackson, Michael Rowlands, Daniel Miller - Google Books. ISBN 9781134733910. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- "Brent Cross - the historical link with Harringay". www.harringayonline.com. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- "IRA bomb causes chaos for commuters". Herald Scotland. 17 December 1991. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- Armed robbers on motorbikes raid Brent Cross jeweller BBC News. 6 November 2012 Retrieved 6 November 2012

- "Brent Cross Cricklewood regeneration". Barnet Council. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011.

- "Report to London Borough of Barnet Assets, Regeneration and Growth Committee, 12 March 2018" (PDF).

- Harry Wallop (2016-03-01). "Brent Cross is now 40-years old. Will shopping centres be here in another 40?". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- "An Ode To Brent Cross Shopping Centre". Londonist. 2018-12-11. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- "Brent Cross welcomes 40th anniversary". Hammerson. 1976-03-02. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- "::: CACI - Marketing Solutions :::". October 20, 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-10-20.

- "Brent Cross Shopping Centre to Rival Westfields - News Ian Scott". Ianscott.com. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- "Westfield crowned UK's best shopping centre for 2nd year running". Retail Gazette. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- "A Love Letter to Brent Cross, London's Least Cool Shopping Centre". VICE. 2016-03-07. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- Harry Wallop (2016-03-01). "Brent Cross is now 40-years old. Will shopping centres be here in another 40?". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-04-27.

- (PDF) https://web.archive.org/web/20110607204805/http://www.barnet.gov.uk/developmentframeworkchapter_3.pdf#page=13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-07. Retrieved 2020-04-27. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Horgan, Rob. "Network Rail gives official go ahead for £40M London station". New Civil Engineer.

- "Bus Route Maps: Brent Cross" (PDF). Transport for London. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- Kinik, Anthony (1 August 2008). "Dynamic of the Metropolis: The City Film and the Spaces of Modernity" (PDF). McGill University, Montreal. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- Ahmed, Fatema (April 27, 2015). "In Brent Cross". London Review of Books. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- "19 top secret Bond locations around Britain". The Telegraph. 28 October 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- "The Star Fraction". Worlds Without End. Retrieved 26 November 2017.