Lambeth Palace

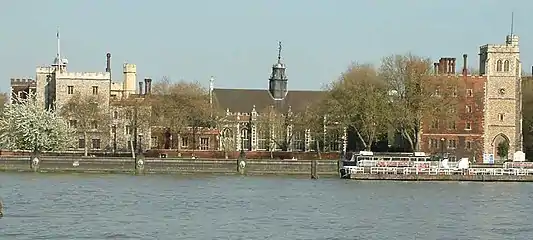

Lambeth Palace is the official London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury. It is situated in north Lambeth, London, on the south bank of the River Thames, 400 yards (370 metres)[1] south-east of the Palace of Westminster, which houses the Houses of Parliament, on the opposite bank.

History

For nearly 800 years, Lambeth Palace has been the London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury, whose original residence was in Canterbury, Kent.[2] Originally called the Manor of Lambeth or Lambeth House, the site was acquired by the archbishopric around AD 1200 and has the largest collection of records of the Church in its library. It is bounded by Lambeth Palace Road to the west and Lambeth Road to the south, but unlike all surrounding land is excluded from the parish of North Lambeth. The garden park is listed and resembles Archbishop's Park, a neighbouring public park; however, it was a larger area with a notable orchard until the early 19th century. The former church in front of its entrance has been converted to the Garden Museum. The south bank of the Thames along this reach, not part of historic London, developed slowly because the land was low and sodden: it was called Lambeth Marsh, as far downriver as the present Blackfriars Road. The name "Lambeth" embodies "hithe", a landing on the river: archbishops came and went by water, as did John Wycliff, who was tried here for heresy. In the Peasants' Revolt of 1381, the Palace was attacked.

The oldest remaining part of the palace is the Early English chapel. Lollards' Tower, which retains evidence of its use as a prison in the 17th century, dates from 1435 to 1440. The front is an early Tudor brick gatehouse built by Cardinal John Morton and completed in 1495. Cardinal Pole lay in state in the palace for 40 days after he died there in 1558. The fig tree in the palace courtyard is possibly grown from a slip taken from one of the White Marseille fig trees here for centuries (reputedly planted by Cardinal Pole). In 1786,[3] there were three ancient figs, two "nailed against the wall" and still noted in 1826 as "two uncommonly fine... traditionally reported to have been planted by Cardinal Pole, and fixed against that part of the palace believed to have been founded by him. They are of the white Marseilles sort, and still bear delicious fruit. ...On the south side of the building, in a small private garden, is another tree of the same kind and age."[4] By 1882, their place had been taken by several massive offshoots.[5] The notable orchard of the medieval period has somewhat given way to a mirroring public park adjoining and built-up roads of housing and offices. The palace gardens were listed grade II in October 1987.[6]

The great hall was completely ransacked, including the building material, by Cromwellian troops during the English Civil War. After the Restoration, it was completely rebuilt by archbishop William Juxon in 1663 (dated) with a late Gothic hammerbeam roof. The choice of a hammerbeam roof was evocative, as it reflected the High-Church Anglican continuity with the Old Faith (the King's brother was an avowed Catholic) and served as a visual statement that the Interregnum was over. As with some Gothic details on University buildings of the same date, it is debated among architectural historians whether this is "Gothic survival" or an early work of the "Gothic Revival". The diarist Samuel Pepys recognised it as "a new old-fashioned hall".

The building is listed in the highest category, Grade I, for its architecture – its front gatehouse with its tall, crenellated gatehouse resembles Hampton Court Palace's gatehouse which is also of the Tudor period, however Morton's Gatehouse was at its very start, in the 1490s, rather than in the same generation as Cardinal Wolsey's wider, similarly partially stone-dressed deep red brick façade. While this is the most public-facing bit, it is not the oldest at north-west corner, the Water Tower or Lollards' Tower mentioned above is made of Kentish Ragstone with ashlar quoins and a brick turret is much older.[7]

Among the portraits of the archbishops in the Palace are works by Hans Holbein, Anthony van Dyck, William Hogarth and Sir Joshua Reynolds.

New construction was added to the building in 1834 by Edward Blore (1787–1879), who rebuilt much of Buckingham Palace later, in neo-Gothic style and it fronts a spacious quadrangle. The buildings form the home of the Archbishop, who is ex officio a member of the House of Lords and is regarded as the first among equals in the Anglican Communion.

Lambeth Palace is home to the Community of Saint Anselm, an Anglican religious order that is under the patronage of the Archbishop of Canterbury.[8]

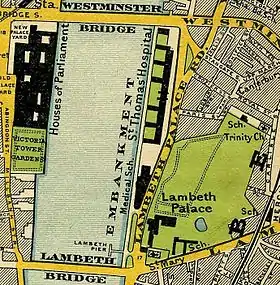

Map of 1897, showing Lambeth Palace, Lambeth Bridge, the Houses of Parliament and Westminster Bridge

Map of 1897, showing Lambeth Palace, Lambeth Bridge, the Houses of Parliament and Westminster Bridge The Guard Room

The Guard Room The great hall with Cardinal Pole's fig tree in front

The great hall with Cardinal Pole's fig tree in front Lambeth Palace from the south circa 1685.

Lambeth Palace from the south circa 1685. Lambeth Palace main entrance

Lambeth Palace main entrance The 19th-century range

The 19th-century range

Library

Within the palace precincts is Lambeth Palace Library, the official library of the Archbishop of Canterbury, and the principal repository of records of the Church of England. It is described as "the largest religious collection outside of the Vatican".[9]

The Library was founded as a public library by Archbishop Richard Bancroft in 1610. It contains an extensive collection of material relating to ecclesiastical history, including the archives of the archbishops dating back to the 12th century, and those of other church bodies and of various Anglican missionary and charitable societies. Manuscripts include items dating back to the 9th century. The library also holds over 120,000 printed books. In 1996, when Sion College Library closed, Lambeth Palace Library acquired its important holdings of manuscripts, pamphlets, and pre-1850 printed books.

Topics covered range from the history of art and architecture to colonial and Commonwealth history, and numerous aspects of English social, political and economic history. The library is also an important resource for local history and genealogy. For online catalogues, see External links below.

Notable items in the collections include:

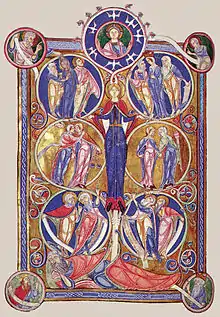

- The Romanesque Lambeth Bible (12th century)

- The Lambeth Choirbook (16th century)

- The Lambeth Homilies (c.1200)

- The Mac Durnan Gospels (late 9th/early 10th centuries)

- The Book of Howth (late 16th century)

- Minuscule 559 (11th century)

- Archives of the Commission for Building Fifty New Churches (1711–1759)

- A copy of the Gutenberg Bible (1450s)

The library was historically located within the main Palace complex. A new purpose-built library and repository, located at the far end of the Palace gardens and with its entrance on Lambeth Palace Road, is scheduled to open in 2021. In addition to the existing library collections, this will house the archival collections of various Church of England institutions currently held at the Church of England Record Centre (opened 1989) in Galleywall Road, Bermondsey.[10]

St Mary-at-Lambeth

Immediately outside the gatehouse stands the former parish church of St Mary-at-Lambeth. The tower dates from 1377 (repaired in 1834); while the body of the church was rebuilt in 1851 to the designs of Philip Hardwick.[11] Older monuments were preserved: they include the tombs of some of the archbishops (including Richard Bancroft), of the gardeners and plantsmen John Tradescant the elder and his son of the same name, and of Admiral William Bligh. St Mary's was deconsecrated in 1972, when the parish was absorbed into the surrounding parish of North Lambeth which has three active churches, the nearest being St Anselm's Church, Kennington Cross.[12][13] The Museum of Garden History (now the Garden Museum) opened in the building in 1977, taking advantage of its Tradescant associations.

See also

- Old Palace, Canterbury, within the precincts of Canterbury Cathedral, is the residence of the archbishop when in Canterbury

- List of palaces

- Palace of Whitehall

References

- Google (20 March 2015). "Lambeth Palace" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- Dunton, Larkin (1896). The World and its People. Silver, Burdett. p. 37.

- Andrew Coltee Ducarel, History and Antiquities of the Palace of Lambeth, 1786 (as Biblioteca Topographica Britannica, vol. II pt 5, 1790)

- Thomas Allen, The History and Antiquities of the Parish of Lambeth 1826:229, paraphrasing Ducarel.

- "It were a grave omission to pass over unnoticed the 'Lambeth fig-trees.' Two of extraordinary size, supposed to have been planted by Cardinal Pole, formerly stood near the east end of the old garden front: they have long ago died, but three or four thriving offshoots, now grown into venerable trees, may still be seen basking on the sunny side of the Great Hall" (John Cave-Browne, Lambeth palace and its associations, 1882:310); "It was Cardinal Pole who is said to have planted the two fig-trees in Lambeth garden, which were still to be seen in 1806, while slips taken from the original plants are now flourishing trees." (Robert Sangster Rait and Caroline C. Morewood, English episcopal palaces (province of Canterbury), 1910:74)

- Historic England. "Lambeth Palace (Grade II) (1000818)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- Historic England. "Lambeth Palace (Grade I) (1116399)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- Lodge, Carey (18 September 2015). "Archbishop Welby launches monastic community at Lambeth Palace". Christian Today. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- "Lambeth Palace". The Archbishop of Canterbury. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- "New Library News". Lambeth Palace Library. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Garden Museum (formerly church of St Mary at Lambeth) Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1000818)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- Map of North Lambeth parish A Church Near You church finder - Church of England

- Lambeth Mission St Mary A Church Near You church finder - Church of England

Bibliography

- Palmer, Richard; Brown, Michelle P., eds. (2010). Lambeth Palace Library: Treasures from the Collections of the Archbishops of Canterbury. London: Scala. ISBN 9781857596274.

- Stourton, James (2012). Great Houses of London. London: Frances Lincoln. ISBN 978-0-7112-3366-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lambeth Palace. |

- Official website

- Lambeth Palace Library official website

- Very detailed architectural description – from the Survey of London online

- Library catalogue of printed books

- Library catalogue of manuscripts and archives