Cades Cove

Cades Cove is an isolated valley located in the Tennessee section of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, USA. The valley was home to numerous settlers before the formation of the national park. Today Cades Cove, the single most popular destination for visitors to the park, attracts more than two million visitors a year because of its well preserved homesteads, scenic mountain views, and abundant display of wildlife.[1] The Cades Cove Historic District is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Geology

Geologically, Cades Cove is a type of valley known as a "limestone window", created by erosion that removed the older Precambrian sandstone, exposing the younger Paleozoic limestone beneath.[2] More weathering-resistant formations, such as the Cades sandstone which underlies Rich Mountain to the north and the Elkmont and Thunderhead sandstones which form the Smokies crest to the south surround the cove, leaving it relatively isolated within the Smokies. As with neighboring limestone windows such as Tuckaleechee to the north and Wear Cove to the east, the weathering of the limestone produced deep, fertile soil, making Cades Cove attractive to early farmers.[3]

The majority of the rocks that make up Cades Cove are unaltered sedimentary rocks formed between 340 million and 570 million years ago during the Ordovician Period.[4] The Precambrian rocks that comprise the high ridges surrounding the cove are Ocoee Supergroup sandstones, formed approximately one billion years ago.[5] The mountains themselves were formed between 200 million and 400 million years ago during the Appalachian orogeny, when the North American and African plates collided, thrusting the older rock formations over the younger formations.[6]

Gregory's Cave

The fracturing and weathering of the limestone and sandstone in Cades Cove has led to the formation of several caves in the vicinity, the two largest of which are Gregory's Cave and Bull Cave.[3] Bull Cave, at 924 feet (281 m), is the deepest cave in Tennessee.[7] Trilobite and brachiopod fossils have been found in Gregory's Cave.[8]

The entrance to Gregory's Cave is approximately 10 feet (3.0 m) wide and 4 feet (1.2 m) high. The cave consists primarily of one large passage that averages 20 to 55 feet (17 m) wide and 15 feet (4.6 m) high. This passage is 435 feet (133 m) long and a side passage to the right (south) is developed about 300 feet (91 m) from the entrance. This side passage ends after about 100 feet (30 m). In the vicinity of this side passage are "tally marks" on the wall, which were typically left by saltpeter miners. The dirt on this side of the cave has been excavated and removed and pick marks are still visible in the dirt. Saltpeter mining occurred in this region from the late 18th century through the Civil War, so this mining activity must have occurred sometime between 1818, when settlers arrived in Cades Cove and 1865, the end of the Civil War. Since this is a relatively small cave and the amount of dirt in the cave was not extensive, this would have been a small mining operation.[9]

Gregory's Cave is the only cave in the national park that was ever developed as a commercial cave. The cave was opened to the public in July 1925. After the Gregory property was bought for the national park in 1935, the Gregory family was given a "lifetime dowry" and the owner, J. J. Gregory's wife, Elvira, was allowed to live there until her death on March 26, 1943. One of her sons was allowed to remain on the property until he harvested his crop in the fall of 1943, after which the property was completely owned by the National Park Service.

Donald K. MacKay, a geologist with the National Park Service, reported that the Gregory family was still showing the cave commercially as late as 1935.[10] At that time the admission price was 50 cents for adults and children were admitted free.

During its history as a commercial cave, Gregory's Cave had walkways, which were made of wood in some places, and electric lights. Wesley Herman Gregory, son of J. J. Gregory, reported that the lighting system was a "Delco System"[11] This may have been a generator producing electricity for the lights inside the cave.

During the Cold War, Gregory's Cave was designated as a fallout shelter, with an assigned capacity of 1,000 people. The cave was stocked with food, water, and other emergency supplies.

Gregory's Cave is now securely gated and entrance is by permit only from the National Park Service. Entrance is generally restricted to scientific researchers.

History

Early history

Throughout the 18th century, the Cherokee used two main trails to cross the Smokies from North Carolina to Tennessee en route to the Overhill settlements. One was the Indian Gap Trail, which connected the Rutherford Indian Trace in the Balsam Mountains to the Great Indian Warpath in modern-day Sevier County. The other was a lower trail that crested at Ekaneetlee Gap, a col just east of Gregory Bald.[12] This trail traversed Cades Cove and Tuckaleechee Cove before proceeding along to Great Tellico and other Overhill towns along the Little Tennessee River. European traders were using these trails as early as 1740.[13]

By 1797 (and probably much earlier), the Cherokee had established a settlement in Cades Cove known as "Tsiya'hi," or "Otter Place."[14] This village, which may have been little more than a seasonal hunting camp, was located somewhere along the flats of Cove Creek.[15] Henry Timberlake, an early explorer in East Tennessee, reported that streams in this area were stocked with otter, although the otter was extinct in the cove by the time the first European settlers arrived.[16]

Cades Cove was named after a Tsiya'hi leader known as Chief Kade.[16] Little is known of Chief Kade, although his existence was verified by a European trader named Peter Snider (1776–1867), who settled nearby Tuckaleechee Cove.[16] Abrams Creek, which flows through the cove, was named after another local chief, Abraham of Chilhowee. A now-discredited theory suggested that the cove was named after Abraham's wife, Kate.[17]

In 1819, The Treaty of Calhoun ended all Cherokee claims to the Smokies, and Tsiya'hi was abandoned shortly thereafter. The Cherokee would linger in the surrounding forests, however, occasionally attacking settlers until 1838 when they were removed to the Oklahoma Territory (see Trail of Tears).[18]

European settlement

John Oliver (1793–1863), a veteran of the War of 1812, and his wife Lurena Frazier (1795–1888) were the first permanent European settlers in Cades Cove. The Olivers, originally from Carter County, Tennessee, arrived in 1818, accompanied by Joshua Jobe, who had initially persuaded them to settle in the cove. While Jobe returned to Carter County, the Olivers stayed, struggling through the winter and subsisting on dried pumpkin given to them by friendly Cherokees. Jobe returned in the Spring of 1819 with a herd of cattle in tow, and gave the Olivers two milk cows to ease their complaints.[19]

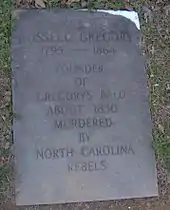

In 1821, William "Fighting Billy" Tipton (1761–1849), a veteran of the American Revolution and son of State of Franklin opponent John Tipton, bought up large tracts of Cades Cove which he in turn sold to his sons and relatives, and settlement began to boom. In the 1820s, Peter Cable, a farmer of German descent, arrived in the cove and designed an elaborate system of dykes and sluices that helped drain the swampy lands in the western part of the cove.[20] In 1827, Daniel Foute opened the Cades Cove Bloomery Forge to fashion metal tools.[21] Robert Shields arrived in the cove in 1835, and would erect a tub mill on Forge Creek. His son, Frederick, built the cove's first grist mill. Other early settlers would build houses on the surrounding mountains, among them Russell Gregory (1795–1864), for whom Gregory Bald is named, and James Spence, for whom Spence Field is named.[22]

Between 1820 and 1850, the population of Cades Cove grew to 671, with the size of cove farms averaging between 150 and 300 acres (0.6 and 1.2 km²).[23] The early cove residents, although relatively self-sufficient, were dependent upon nearby Tuckaleechee Cove for dry goods and other necessities.[24]

The isolation often attributed to Cades Cove is probably exaggerated. A post office was established in the cove in 1833, and Sevierville post master Philip Seaton set up a weekly mail route to the cove in 1839. Cades Cove had telephone service as early as the 1890s, when Dan Lawson and several neighbors built a phone line to Maryville. By the 1850s, various roads connected Cades Cove with Tuckaleechee and Montvale Springs, some of which are still maintained as seasonal passes or hiking trails.[25]

Religion in Cades Cove

Religion was an important part of life in Cades Cove from its earliest days, a reflection of the efforts of John and Lucretia Oliver.[26] The Olivers managed to organize a branch of the Miller's Cove Baptist Church for Cades Cove in 1825. After briefly realigning themselves with the Wear's Cove Baptist Church, the Cades Cove Baptist Church was pronounced an independent entity in 1829.[27]

In the 1830s, a division in Baptist churches known as the Anti-mission Split occurred throughout East Tennessee.[28] The split developed over disagreement about whether missions and other "innovations of the day" were authorized by Scripture. This debate made its way to Cades Cove Baptist Church in 1839, becoming so emotionally charged as to require the intervention of the Tennessee Association of United Baptists. In the end, thirteen members of the congregation departed to form the Cades Cove Missionary Baptist Church later that year, and the remaining congregation changed its name in 1841 to the Primitive Baptist Church.[29] The Primitive Baptists believe in a strict, literal interpretation of Scripture. William Howell Oliver (1857–1940), pastor of the Primitive Baptist Church from 1882 to 1940, explained:

We believe that Jesus Christ Himself instituted the Church, that it was perfect at the start, suitably adopted in its organization to every age of the world, to every locality of earth, to every state and condition of the world, to every state and condition of mankind, without any changes or alterations to suit the times, customs, situations, or localities.[30]

The Primitive Baptists remained the dominant religious and political force in the cove with their meetings interrupted only by the Civil War. The Missionary Baptists,[31] with a much smaller congregation, continued to meet intermittently throughout the 19th century.

The Cades Cove Methodist Church was organized in the 1820s, probably through the efforts of such circuit riders as George Eakin. The Methodist congregation, like that of the Missionary Baptists, was small.[32]

The Civil War

In the decades before the Civil War, Blount County, Tennessee, was a hotbed of abolitionist activity. The Manumission Society of Tennessee was active in the county as early as 1815, and the Quakers— who were relatively numerous in Blount at the time— were so vehemently opposed to slavery that they fought alongside the Union army, in spite of their pacifist agenda.[33] The founder of Maryville College, Rev. Isaac L. Anderson, was a staunch abolitionist who often gave sermons in Cades Cove. Blount doctor Calvin Post (1803–1873) was believed to have set up an Underground Railroad stop within the cove in the years preceding the war.[33] With such sentiment and influence, Cades Cove remained staunchly pro-Union, regardless of the destruction it suffered throughout the war (there were some exceptions, however, such as the cove's affluent entrepreneur and Confederate sympathizer, Daniel Foute).

In 1863, Confederate bushwhackers from Hazel Creek and other parts of North Carolina began making systematic raids into Cades Cove, stealing livestock and killing any Union supporter they could find. Elijah Oliver (1829–1905), a son of John Oliver and a Union sympathizer, was forced to hide out on Rich Mountain for much of the war. Calvin Post had also gone into hiding, and with the death of John Oliver in 1863, the cove had lost most of its original leaders.[34]

Although Federal forces occupied Knoxville in 1863, Confederate raids into Cades Cove continued. A pivotal figure at this time was Russell Gregory, who had originally vowed to remain neutral after his son defected to the Confederate cause. Gregory organized a small militia, composed mostly of the cove's elderly men, and in 1864 ambushed a band of Confederate marauders near the junction of Forge Creek and Abrams Creek. The Confederates were routed and chased back across the Smokies to North Carolina. Although this largely put an end to the raids, a band of Confederates managed to sneak into the cove and kill Gregory just two weeks later.[35]

Cades Cove suffered from the effects of the Civil War for most of the rest of the 19th century. Only around 1900 did its population return to pre-war levels. The average farm was much less productive, however, and the cove residents were suspicious of any form of change. It wasn't until the Progressive Era that the cove recovered economically.[36]

Moonshining and Prohibition

The Chestnut Flats area of Cades Cove, located at the base of Gregory Bald, was well known for producing high-quality corn liquor.[37] Among the more prominent moonshine distillers was Josiah "Joe Banty" Gregory (1870–1933), the son of Matilda "Aunt Tildy" Shields by her first marriage.[38] The Primitive Baptists, especially William Oliver and his son, John W. Oliver (1878–1966), were fervently opposed to the distilling or consumption of alcohol, and the practice was largely confined to Chestnut Flats. John W. Oliver, a mail carrier in the cove, often found stills on his mail route and reported them to authorities. Oliver would later deride the image of the moonshiner as an integral part of the mountaineer stereotype:

All these men are public outlaws, and were never recognized as true, loyal mountaineers or as true American citizens, by the rank and file of the mountain people.[39]

In 1921, Josiah Gregory's still was raided by the Blount County sheriff. Although it was later revealed that the sheriff was tipped off by a surveyor in the area, the Gregorys blamed the Olivers. On the night following the raid, the barns of both William and John W. Oliver were burned, destroying a large portion of the family's livestock and tools.[40] Shortly thereafter, Gregory's son was assaulted by Asa and John Sparks after a prank-gone-wrong. In response, Gregory and his brother, Dana, hunted down and shot the Sparks brothers on Christmas night in 1921. Both of the Gregorys were convicted of barn burning and later convicted of felonious assault. After serving only six months, however, they were pardoned and personally escorted home by Governor Austin Peay.[41]

As mentioned previously, Gregory's Cave may also have been involved in the manufacture of moonshine.

The National Park

Of all the Smoky Mountain communities, Cades Cove put up the most resistance to the formation of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The cove residents were initially assured their land would not be incorporated into the park, and welcomed its formation.[42] By 1927, the winds had changed, however, and when the Tennessee General Assembly passed a bill approving money to buy land for the national park, it gave the Park Commission the power to seize properties within the proposed park boundaries by eminent domain. Long-time residents of Cades Cove were outraged. The head of the Park Commission, Colonel David Chapman, received several threats, including an anonymous phone call warning him that if he ever returned to Cades Cove, he would "spend the next night in hell."[43] Shortly thereafter, Chapman found a sign near the cove's entrance that read {sic}:

COL. CHAPMAN: YOU AND HOAST ARE NOTFY, LET THE COVE PEOPL ALONE. GET OUT. GET GONE. 40 M. LIMIT.[44]

The "40 mile" (64 km) limit referred to the distance between Cades Cove and Chapman's hometown of Knoxville. Despite these threats, Chapman initiated a condemnation suit against John W. Oliver in July 1929. The court, however, ruled in favor of Oliver, reasoning that the federal government had never said Cades Cove was essential to the national park. Shortly after the verdict, the Secretary of the Interior officially announced that the cove was necessary, and another condemnation suit was filed. This time, Oliver lost, with the case going all the way to the Tennessee Supreme Court. Oliver would return to court several times over the value of his 375-acre (1.5 km²) tract, which he said was worth $30,000, although the court awarded him just $17,000 plus interest. After attaining a series of one-year leases, Oliver finally abandoned his property on Christmas Day in 1937.[45] The Primitive Baptist Church congregation continued to meet in Cades Cove until the 1960s in defiance of the Park Service, which wanted to develop the land where their church was located.[46]

For about one hundred years before the creation of the national park, much farming and logging was done in the valley, as the main source of economic development for the people living in the cove, both leading to massive deforestation. At first, the National Park Service planned to let the cove return to its natural forested state.[47] It ultimately yielded to requests by the Great Smoky Mountain Conservation Association to maintain Cades Cove as a meadow. On the advice of contemporary cultural experts such as Hans Huth, the service demolished the more modern structures, leaving only the primitive cabins and barns which were considered most representative of pioneer life in early Appalachia. [48]

Historical structures in Cades Cove

Cades Cove Historic District | |

Becky Cable House | |

| |

| Location | 10 mi. SW of Townsend in Great Smoky Mountains National Park |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Townsend, Tennessee |

| Built | 1818 |

| NRHP reference No. | 77000111 |

| Added to NRHP | July 13, 1977 |

Cades Cove has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places as an historic district since July 13, 1977.[49] The historic district is bounded by the 2,000-foot (610 m) elevation contour (that is, it comprises all areas below that elevation) and includes both historic buildings and prehistoric archaeological sites.[50]

The National Park Service currently maintains several buildings in Cades Cove that are representative of pioneer life in the 19th-century Appalachia. By the time the cove was incorporated into the park, most residents lived in relatively modern frame houses, rather than the log cabins that predominate among the buildings preserved in the cove.

The following are listed in the order they are approached along the Cades Cove Loop Road:

1. The John Oliver Cabin, constructed c. 1822-1823 by the cove's first permanent European settlers. Dunn reports that the Olivers spent the winter of 1818-1819 in an abandoned Cherokee hut, and built a crude structure the following year. The Oliver cabin was built as a replacement for this first crude structure, which was located a few yards behind the cabin.

John Oliver Cabin

John Oliver Cabin John Oliver Cabin window/chimney detail

John Oliver Cabin window/chimney detail Interior of John Oliver Cabin

Interior of John Oliver Cabin

2. The Primitive Baptist Church, constructed in 1887. The church was organized as the Cades Cove Baptist Church in 1827, and renamed "Primitive Baptist" after the Anti-missions Split in 1841. The Olivers and Russell Gregory are buried in its cemetery.

Primitive Baptist Church

Primitive Baptist Church Inside Primitive Baptist Church

Inside Primitive Baptist Church The Grave of Russell Gregory

The Grave of Russell Gregory

3. The Cades Cove Methodist Church, constructed in 1902. Methodists were active in the cove as early as the 1820s, and built their first meeting house in 1840.

Cades Cove Methodist Church

Cades Cove Methodist Church Inside Methodist Church

Inside Methodist Church 19th-century graveyard

19th-century graveyard

4. The Cades Cove Missionary Baptist Church, current building constructed in 1915-1916. The church was formed from a small faction of Cades Cove Baptists in 1839 who had broken off from the main church due to the debate over missions, which the Cades Cove Baptists didn't consider authorized by scripture.

Missionary Baptist Church, front

Missionary Baptist Church, front Missionary-Baptist-Church, side

Missionary-Baptist-Church, side Inside Missionary Baptist Church, sanctuary

Inside Missionary Baptist Church, sanctuary Inside Missionary Baptist Church, looking outside

Inside Missionary Baptist Church, looking outside Pew detail, Missionary Baptist Church

Pew detail, Missionary Baptist Church

5. The Myers Barn, constructed in 1920. The Myers Barn is a more modern-looking hay barn located along the trail to the Elijah Oliver Place.

6. The Elijah Oliver Place, constructed in 1866. Elijah Oliver (1829–1905) was the son of John and Lucretia Oliver. His original farm was destroyed during the U.S. Civil War by Confederate marauders. The homestead includes a dog-trot cabin, a chicken coop, a corn crib, a spring house, and a crude stable.

Elijah Oliver Place

Elijah Oliver Place Elizah Oliver window/chimney detail

Elizah Oliver window/chimney detail Elijah Oliver Cabin door, detail

Elijah Oliver Cabin door, detail

7. The John Cable Grist Mill, constructed in 1868. John P. Cable (1819–1891), a nephew of Peter Cable, had to construct a series of elaborate diversions along Mill Creek and Forge Creek to get enough water power for the mill's characteristic overshot wheel.[51]

Gristmill at John Cable house

Gristmill at John Cable house Grist Mill

Grist Mill

8. The Becky Cable House, constructed in 1879. This building, adjacent to the Cable Mill, was initially used by Leason Gregg as a general store. In 1887, he sold it to John Cable's spinster daughter, Rebecca Cable (1844–1940). A Cable family tradition says that Rebecca never forgave her father and refused to marry after her father broke off one of her childhood romances. Various buildings have been moved from elsewhere in the cove and placed near the Cable mill, including a barn, a carriage house, a chicken coop, a molasses still, a sorghum press, and a replica of a blacksmith shop.

Becky Cable House

Becky Cable House

9. The Henry Whitehead Cabin, constructed 1895-1896. This cabin, located on Forge Creek Road near Chestnut Flats, was built by Matilda "Aunt Tildy" Shields and her second husband, Henry Whitehead (1851–1914). Shields' sons from her first marriage were prominent figures in the cove's moonshine trade.

Henry Whitehead Cabin

Henry Whitehead Cabin

10. The Dan Lawson Place, built by Peter Cable in the 1840s and acquired by Dan Lawson (1827–1905) after he married Cable's daughter, Mary Jane. Lawson was the cove's wealthiest resident. The homestead includes a cabin (still called the Peter Cable cabin), a smokehouse, a chicken coop, and a hay barn.

Dan Lawson Place

Dan Lawson Place Dan Lawson window/siding detail

Dan Lawson window/siding detail

11. The Tipton Place, built in the 1880s by the descendants of Revolutionary War veteran William "Fighting Billy" Tipton. The paneling on the house was a later addition. Along with the cabin, the homestead includes a carriage house, a smokehouse, a woodshed, and the oft-photographed double-cantilever barn.

Tipton Corn Crib

Tipton Corn Crib Double- cantilever barn at the Tipton Place

Double- cantilever barn at the Tipton Place Tipton-Oliver-Blacksmith-Shop

Tipton-Oliver-Blacksmith-Shop Tipton Cabin

Tipton Cabin Side view of Tipton Place

Side view of Tipton Place Interior of Tipton Place

Interior of Tipton Place

12. The Carter Shields Cabin, a rustic log cabin built in the 1880s.

Carter Shields Cabin, the last homestead on the Cades Cove automobile tour

Carter Shields Cabin, the last homestead on the Cades Cove automobile tour Carter Shields Cabin window, detail

Carter Shields Cabin window, detail

Touring

Though geographically isolated, Cades Cove today is a popular tourist destination in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. A one-way, eleven mile (18 km) paved loop around Cades Cove draws thousands of visitors daily. The eleven miles may take more than four hours to traverse and view the sites during tourist season. The cove receives approximately 5 million visitors per year and is the most popular destination in the Great Smoky Mountain National Park.

The cove draws attention for numerous black bear sightings, although many enthusiasts make the trip for the abundant hiking access and the well-preserved 19th-century homesteads. On most days, multiple deer can be seen in the meadows and woods throughout the cove. Popular hiking trails within the cove include the trails to Abrams Falls (a nearly five-mile round trip hike) and Gregory Bald, the latter named after Russell Gregory, a prominent resident of the cove. In addition to hiking and general sightseeing, horseback (see below) and bicycle riding are popular activities.

References

- Kris Christen, Trapped in the Cove Archived 2006-07-14 at the Wayback Machine, Sightline, Vol. 3 No. 1, Winter/Spring 2002, University of Tennessee Energy, Environment and Resources Center (EERC)

- Harry Moore, A Roadside Guide to the Geology of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1988), 29.

- Moore, 29.

- Moore, 17.

- Moore, 12-13.

- Moore, 23-27.

- Gulden, Bob (June 20, 2013). "USA Deepest Caves". Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- Moore, 35.

- Larry Matthews, Caves of Knoxville and the Great Smoky Mountains (Knoxville, Tennessee: National Speleological Society, 2008), pp. 157-180.

- Donald K. MacKay, Geology of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park (14 September 1935). Report on file at the Sugarlands Visitor Center Library.

- From a transcript of a conversation with Wesley Herman Gregory, son of J. J. Gregory, dated 22 April 1971. Transcript on file at the Sugarlands Visitor Center Library.

- Michael Strutin, History Hikes of the Smokies (Gatlinburg: Great Smoky Mountains Association, 2003), 322-323.

- Dunn, Durwood (1988). Cades Cove: The Life and Death of An Appalachian Community. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. p. 6.

- Vicki Rozema, Footsteps of the Cherokees: A Guide to the Eastern Homelands of the Cherokee Nation (Winston-Salem, North Carolina: John F. Blair, 1995.

- James Mooney, Myths of the Cherokee and Sacred Formulas of the Cherokee (Nashville: Charles Elder, 1972), 538.

- Rozema, p. 183.

- Dunn, 260.

- Dunn, 13.

- Dunn, 1-9.

- Dunn, 16-17.

- Dunn, 20.

- Dunn, 43-44.

- Dunn, 68.

- Dunn, 67.

- Dunn, 82-86.

- Dunn, 100.

- Dunn, 102-103.

- Dunn, 112.

- Dunn, 112-113.

- Dunn, 104.

- Not the same as the American Baptist Association of Missionary Baptists headquartered in Texarkana, Texas

- Dunn, 119-120.

- Dunn, 125.

- Dunn, 134.

- Dunn, 135-136.

- Dunn, 143-144.

- Michael Frome, Strangers In High Places: The Story of the Great Smoky Mountains (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1994), 334.

- Frome, 334.

- Daniel Pierce, The Great Smokies: From Natural Habitat to National Park (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2000), 21.

- Dunn, 235-236.

- Dunn, 238-239.

- Dunn, 242-246.

- Carlos Campbell, Birth of a National Park In the Great Smoky Mountains (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1969), 97-101.

- Campbell, 98.

- Pierce, 162.

- Pierce, 166.

- Campbell, 147.

- Dunn, xiii-xiv.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

- Dunn, 81-82.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cades Cove. |

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Cades Cove

- Cades Cove, Great Smoky Mountains National Park website

- The Great Smoky Mountains Association — Non-profit partner of the National Park, creator of popular park maps, guides, and books, and operates all official park information and visitor centers

- Cades Cove photos, National Register of Historic Places

- Cades Cove Preservation Association

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park: Plan Your Visit: Cades Cove

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park: Maps