Capture of Trônes Wood

The Capture of Trônes Wood (8–14 July) was a tactical incident in the First World War, fought by the British Fourth Army and the German 2nd Army, during the Battle of the Somme. Trônes Wood lay on the northern slope of Montauban ridge, between Bernafay Wood and Guillemont. The wood dominated the southern approach to Longueval and Trônes Alley, a German communication trench between Bernafay Wood and the northern tip of Trônes Wood to Guillemont. A light railway ran through the centre, which was in a dip formed by the east end of Caterpillar Valley sloping away to the west. The wood was pear-shaped, with a base about 400 yd (370 m) wide on Montauban ridge, the rest of the wood running north for about 1,400 yd (1,300 m), coming to a point on a rise towards Longueval village.

| Capture of Trônes Wood | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of The Battle of the Somme of the First World War | |||||||

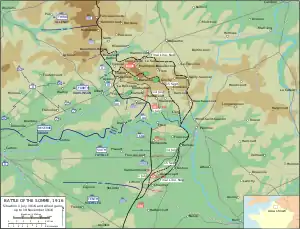

Map of the Battle of the Somme, 1916 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 3 divisions | elements of 4 divisions | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| c. 3,827 | |||||||

Trônes Wood Trônes Wood, on the northern slope of Montauban ridge between Bernafay Wood and Guillemont | |||||||

The wood had dense undergrowth which retarded movement, made it difficult to keep direction and during the battle the trees were brought down by shellfire, becoming entangled with barbed wire and strewn with German and British dead. The British attacks were part of preliminary operations, to reach ground from which to begin the second British general attack of the Battle of the Somme, against the German second position from Longueval to Bazentin le Petit on 14 July. The German defenders fought according to a policy of unyielding defence and immediate counter-attack to regain lost ground, intended to delay the Anglo-French advance south of the Albert–Bapaume road and give time for reinforcements sent to the Somme front to arrive.

Background

On 1 July the Anglo-French bombardment on the right flank of the Fourth Army had been highly effective, due to good observation over the German positions and had achieved tactical surprise. The German 28th Reserve Division had been defeated and only saved from destruction by reinforcements from the 10th Bavarian Division. In the XIII Corps (30th Division, 18th (Eastern) Division and the 9th (Scottish) Division in reserve) area the success was complete, the troops on the right flank were in touch with the French south of Bernafay Wood, Montauban had been consolidated and observation gained over Caterpillar Valley. XIII Corps was ordered to prepare to attack Mametz Wood with XV Corps on the left. There was severe congestion in the Maricourt Salient, where there were few roads to supply XIII Corps and XX Corps of the French Sixth Army, which delayed a resumption of the attack, although the road from Maricourt to Montauban was open by 6:00 p.m. Reconnaissance by the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) reported that the German second line from Guillemont to Bazentin le Grand was strongly held. On 1/2 July two German counter-attacks in the early hours were repulsed by shrapnel-fire from the 30th divisional artillery, which also experimented with a Thermite barrage on Bernafay Wood. The 27th Brigade of the 9th Division relieved a brigade of the 30th Division near Montauban and the captured ground was consolidated.[1]

On 2 July Haig met Rawlinson and directed that attacks should continue on the right flank, although Rawlinson was concerned over a lack of heavy howitzer ammunition. On 3 July Haig met Joffre and Foch and announced that he was concentrating British efforts south of the Albert–Bapaume road, despite Joffre's objections. The Fourth Army would continue the attack between Montauban and Fricourt, before attacking the German second position, from Longueval to Bazentin-le-Petit, as the Reserve Army advanced north-east towards Pozières. The attack front was shortened by 3.1 mi (5 km) and XIII Corps and XV Corps were to consolidate their positions, then advance towards Trônes Wood and Mametz Wood.[2] Front-line officers in XIII Corps reported that German resistance was weak and that delay would give the defence time to recover. Congreve, the XIII Corps commander, instructed the 30th Division and 9th Division commanders to capture Trônes Wood, before a general attack on the Fourth Army front intended for 10 July.[3] A local attack was planned, in support of the French, for the morning of 7 July, on high ground at Maltz Horn Farm and Hardecourt, which overlooked the south end of Trônes Wood. The attack was postponed, after a German counter-attack on 6 July, recaptured part of Favières Wood further south, which delayed French preparations by 24 hours.[4]

Prelude

British offensive preparations

On 2 July, patrols from the 30th Division found Bernafay Wood undefended and took 17 prisoners from Reserve Infantry Regiment 51, who had retreated there during the morning.[lower-alpha 1] At 9:00 p.m. on 3 July, after a short bombardment, two battalions of the 27th Brigade (9th Division), advanced on a line from the Briqueterie to Montauban and reached the eastern edge by 11:30 p.m., against slight opposition. A few prisoners were taken from the I and III battalions Reserve Infantry Regiment 51, which had withdrawn during the bombardment; four field guns left behind the night before by the 6th Battery, Foot Artillery Regiment 57 were captured. A further advance towards Trônes Wood found it occupied but the 18th (Eastern) Division occupied Caterpillar Wood early on 3 July and Marlboro' Wood unopposed on 4 July.[6][lower-alpha 2]

On 4 July Haig stressed the importance of the rapid capture of Trônes Wood and next day arranged with the French for the right boundary of the Fourth Army to be moved south. General Headquarters (GHQ) also announced a ration of 56,000 rounds of 18-pounder field gun ammunition and 4,920 rounds of 6-inch howitzer ammunition per day, plus the use of some French heavy guns on loan to the British. General Henry Rawlinson co-ordinated the attack on the wood with General Émile Fayolle on 6 July but the attack was postponed because of a German counter-attack. Haig issued a memorandum on policy, that advantage must be taken of German confusion and low morale after the 15 battalions opposite the right flank of the Fourth Army had suffered so many casualties.[8][lower-alpha 3]

British plans of attack

After a preliminary bombardment on 8 July, XIII Corps was to occupy the south end of Trônes Wood, Maltz Horn Trench and capture Maltz Horn Farm, as the French 39th Division on the right took the rest of Maltz Horn Trench, up to Hardecourt knoll and from there to Hardecourt.[10] No man's land opposite the British was 1,100–1,500 yd (1,000–1,400 m) wide and under German observation but the western approach from Bernafay Wood, held by the 9th Division was not visible form Longueval. An attack could then be made from the south-west on Maltz Horn Farm, out of view of the German second position. On 9 July the 30th Division plan was to attack at 3:00 a.m. after a short bombardment. Next day another attack was mounted after a German counter-attack recovered the wood and recaptured the western edge. On 11 July British troops were withdrawn and a bombardment, said by German witnesses to be "the fiercest yet experienced", opened at 2:40 a.m. before the attack. On 12 July the 30th Division reported that it held the wood but that all three brigades were exhausted, so the 55th Brigade of the 18th (Eastern) Division was attached that morning.[11]

When the 30th Division reported on 12 July that the Germans had again retaken the wood, except for the southern portion, the division was relieved by the 18th (Eastern) Division, which was ordered to take the wood at all costs. Two battalions of the 54th Brigade were added to the 55th Brigade. The 18th (Eastern) Division battalions were dispersed around the salient and German bombardments on La Briqueterie, Trônes Wood, Maltz Horn Farm and Maricourt, had cut telephone communication; no time remained to arrange visual signalling or reconnaissance. The 55th Brigade commander planned for a battalion to attack from the south and occupy the southern half of the wood, an attack by another battalion from Longueval Alley on the north end of the wood above the railway, while a third battalion in Maltz Horn Trench attacked north, to take the strong point at the south-east end of the wood, with the fourth battalion carrying stores to forward dumps. The attack was to start at 7:00 p.m. after a two-hour artillery bombardment, concentrated on Central Trench and the diggings facing Longueval Trench in the north. One battalion was to consolidate the eastern fringe of the wood below the railway line, with machine-gun posts every 100 yd (91 m) and the other battalion the fringe north of the railway.[12]

German defensive preparations

After a counter-attack on the junction of the French Sixth Army and the British Fourth Army on the night of 1/2 June failed, the Second Army organised a new front in the second position, from Assevillers north to Herbecourt, Hem, Maurepas, Guillemont, Longueval and Bazentin le Petit Wood. Further counter-attacks were not possible due to a lack of troops but by 3 July the front from Longueval to Ovillers had been occupied by battalions taken from six divisions. Divisions on the Somme front were reorganised into three groups and air units were reinforced and divided into distant and close reconnaissance, artillery observation, fighting and bombing units. On 5 July, the pause in Anglo-French attacks led General Fritz von Below, to report that the initial crisis had been contained. No more counter-attacks would be made until the situation was clear, in anticipation of more Anglo-French attacks.[13]

German casualties on 7 July from British air-observed artillery-fire were high and communications were cut, leaving commanders ignorant of the situation and many German wounded stranded near the front-line. Sixty-five heavy artillery batteries were sent to the Somme front from 6–13 July along with air reinforcements. Falkenhayn stressed the need to hold the ground from Hardecourt to Trônes Wood, as a base from which to begin an organised counter-attack but all the attacks contemplated were cancelled on 13 July, to be ready to receive the British attack known to be imminent. More Groups were organised using corps headquarters staff, to control the increasing number of divisions reaching the Somme front, Group Gossler with the 123rd Division and parts of the 11th and 12th Reserve divisions, taking over from the Somme to Longueval. Many divisional units had been detached as piecemeal reinforcements and were tired, disorganised and depleted by casualties.[14]

Battle

8–9 July

| Date | Rain mm |

Temp (°F) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 July | 17.0 | 70°–55° | rain |

| 5 July | 0.0 | 72°–52° | dull |

| 6 July | 2.0 | 70°–54° | rain |

| 7 July | 13.0 | 70°–59° | rain |

| 8 July | 8.0 | 73°–52° | dull |

| 9 July | 0.0 | 70°–53° | dull |

| 10 July | 0.0 | 82°–48° | dull |

| 11 July | 0.0 | 68°–52° | dull |

| 12 July | 0.1 | 68°– — | dull |

| 13 July | 0.1 | 70°–54° | dull wind |

| 14 July | 0.0 | — – — | dull |

The British attack began at 8:00 a.m., after a bombardment of Trônes Wood and Maltz Horn Trench. The 2nd Yorkshire of the 21st Brigade (30th Division) moved through Bernafay Wood and formed up along the eastern fringe, then began an advance to the south end of Trônes Wood 400 yd (370 m) away. As the battalion topped a rise mid-way to the wood, massed small-arms fire came from a trench in the south-west corner of the wood and caused many casualties. Attempts to continue the advance failed, the survivors withdrew to Bernafay Wood and efforts by bombers to move along Trônes Alley also failed.[16] Troops of the French 39th Division captured Hardecourt Knoll and the adjacent part of Maltz Horn Trench, which left their left flank vulnerable to fire from the rest of the trench north of Maltz Horn Farm and to machine-guns in the wood.[17]

Another attack was arranged by the British 21st Brigade, with the fresh 2nd Wiltshire at 1:00 p.m., after a bombardment of the German trench in the south-west corner of the wood. The troops found that the Germans had been driven out of the trench by the artillery and entered the wood with few casualties, as a company moved from La Briqueterie up a sunken road towards Maltz Horn Farm, to gain touch with the French. As the British approached in dead ground, the French bombed north, up the trench, diverting the German garrison as the British rushed the trench frontally and then repulsed a small counter-attack from the farm. A German counter-attack in the evening from the north end of the wood was also defeated. The captured trench was on the forward slope of Hardecourt Knoll and overnight, German troops dug in on the reverse slope 300 yd (270 m) beyond. Maltz Horn Farm lay between the two lines and at 5:00 a.m., a British battalion which had moved up overnight rushed the farm.[16]

Reinforcements had reached the troops at the south end of the wood overnight and at 3:00 a.m., a battalion of the 90th Brigade advanced by the sunken road, from La Briqueterie to Maltz Horn Farm then bombed up Maltz Horn Trench, taking 109 prisoners and reached a strong point at the junction of the Guillemont track and the wood. The left-hand battalion advance from Bernafay Wood either side of the light railway, towards the centre and north of Trônes Wood at 3:00 a.m., was delayed by gas and the undergrowth of the wood until 6:00 a.m. The battalion entered the western edge and struggled through the undergrowth, fallen trees and shell-craters. Central Trench along the middle of the wood was captured and the eastern edge was reached by 8:00 a.m., completing the occupation of the wood with patrols advancing northwards.[16] Trônes Wood and Maltz Horn Trench had been held by 2–3 battalions of Reserve Infantry Regiments 38 and 51, 12th Reserve Division and small parties of Infantry Regiment 62, 12th Division, remnants of the original line holding division. During the morning the first elements of the 123rd Division began to arrive, in the area from the Somme to Guillemont.[18][lower-alpha 4] A German bombardment began at 12:30 p.m. and the British battalion in the north of the wood withdrew to Bernafay Wood at 3:00 p.m., as most of the right-had battalion fell back to La Briqueterie, Maltz Horn Trench east of the wood also being abandoned.[21]

German artillery behind Guillemont and Longueval bombarded the wood as II Battalion, Infantry Regiment 182 moved from Ginchy to the second line trench from Guillemont to Waterlot Farm. The move was spotted by the observers in British aircraft, from which a bombardment was called down on the east side of Guillemont, pinning down two of the II Battalion companies. The survivors of Reserve Infantry Regiment 51 were formed into two composite companies, behind two of the II Battalion companies which had arrived; two companies to attack north of the railway and two to the south. Packs were left behind because of the undergrowth in the wood and at 4:15 p.m. the 500 yd (460 m) advance began; no British fire was encountered and the troops entered the wood in a line to keep touch. Some British troops in the undergrowth opened reverse fire until captured and at a strong point in the centre near the railway line, a British party held out until surrounded. The advance reached the west side of the wood at 5:10 p.m. and light signals directed the artillery to lift onto the east edge of Bernafay Wood. The companies trapped behind Guillemont arrived at 5:20 p.m. and relieved the exhausted troops of Reserve Infantry Regiment 51. Touch was gained on the right with Bavarian Infantry Regiment 16, near Longueval and Reserve Infantry Regiment 38 near Arrow Head Copse to the south-east.[22] At 6:40 p.m. a British battalion from the 90th Brigade advanced from La Briqueterie; the Germans in the wood were on the west side and despite German artillery-fire the British reached the wood with few casualties.[23] German snipers in the trees and bombers lurking in the undergrowth, harassed the British troops as they dug a 150 yd (140 m) trench 60 yd (55 m) short of the south-western fringe of the wood during the night, ready to advance into the wood on 10 July.[21]

10–11 July

At 4:00 a.m. the 90th Brigade battalion in the new trench near the wood and a South African company from the 9th Division advanced into the wood in groups of twenty, many of whom got lost while others moved through the wood unopposed and reported it empty. To the west, bombers took part of Longueval Alley from Bernafay Wood past the northern point of Trônes Wood and German troops in the strong point captured the day before in Central Trench were overrun.[24] When the British bombardment had commenced at 3:00 a.m. the German companies at the west side of the wood were withdrawn to the east side, where they saw German troops retire from the south end of the wood to Guillemont, then troops began to trickle out of the north end. The party in the centre fell back to shell-holes 200 yd (180 m) to the east, above the track to Guillemont, ready to retire slowly if pressed. Nothing was seen for an hour, when British prisoners emerged from the south end of the wood, moving under escort to Guillemont. Patrols went back into the wood to scout and at 8:00 a.m. a party of 50 Germans was found in the south end. About 200 troops moved up along the light railway, formed a skirmish line with the other troops present and advanced into south end of the wood. Dead British and German troops were "everywhere" and a small German garrison was found in Central Trench, among dead South African Scottish. Small posts were left along the western edge of the wood and the rest withdrawn to Central Trench, 251 prisoners being sent back to Guillemont. The German troops along the western and southern fringes of the wood were organised into three groups, one near the light railway, one along the south-western edge and one along the southern fringe. Trônes Alley was blocked and the remnants of Infantry Regiment 51 were brought back to the wood north of the light railway.[25]

During the night the 90th Brigade was relieved by the 89th Brigade in Maltz Horn Trench and La Briqueterie. All British troops had been withdrawn from the wood for a bombardment, which began at 2:40 a.m. and at 3:27 a.m. bombers attacked north up Maltz Horn Trench, then stopped short of the south-eastern edge of the wood by mistake. The left-hand battalion advanced to the eastern edge of the wood, to join with the right-hand battalion at the strong point but part veered right under German machine-gun fire, reached the south-eastern edge and dug in when unable to advance further. The rest of the battalion entered the wood on the left and drew back both flanks to the western edge, sending patrols into the wood, which met the German troops reinforced from Guillemont.[26] Reserve Infantry Regiment 106 of the 123rd Division had been held back when the 12th Reserve Division had been relieved but three companies had been sent forward to the area around Guillemont by 11 July, where they met German troops from the wood. Both groups advanced again at 5:30 a.m. and drove back British troops from the eastern edge, took 200 prisoners and prevented the troops still in the wood from being outflanked. The main German body in the wood occupied posts along Central Trench, from where the British troops were not seen in the half-light, until 400 yd (370 m) from the wood. Machine-gun fire from the strong point at Trônes Alley, mistakenly thought by the British to have been captured, diverted the British to the east. Many of the German posts of Company Von Mosch were overrun and others caught in the worst barrage the troops had experienced, many of the survivors retiring to Guillemont. Companies Bache and Lanzendorf were left isolated in the southern end of the wood.[27]

Fighting went on all morning and at noon more German reinforcements took the north end of the wood. Documents found on a German officer taken prisoner by the French, containing information about a counter-attack on Trônes Wood, led to XIII Corps ordering a barrage at about 6:00 p.m.[26] British troops had taken ground near Maltz Horn Trench and German parties nearby withdrew to the area south of Guillemont. A further advance by the British was stopped by fire from the south-east of the wood. More German troops reached the wood at midday and occupied the north end beyond the railway line. By evening the western edge was held by German troops and the reinforcements, most of the south-western corner had been retaken and all of the south, with posts at the fringe and the bulk of the garrison in Central Trench. The rest of I Battalion, Reserve Infantry Regiment 106 was ordered into the wood, to attack south from the railway line at 9:00 p.m. The British barrage inflicted many casualties and delayed the arrival of some German troops until 11:00 p.m. Relief of exhausted troops in the wood was delayed and some retired too soon, leaving posts unoccupied. British troops were able to re-enter the wood unopposed; the German attack was cancelled and the troops used to reinforce the defence. The British moved to the south-eastern edge facing Guillemont and dug in below the strong point at Trônes Alley. A new trench was dug westwards to link with the British troops still in the south-western part of the wood, covered by ambush parties and completed early on 13 July.[28]

12–13 July

A German attack at 9:00 p.m. was ordered, in which the rest of II Battalion, Reserve Infantry Regiment 106 was to advance at 8:30 p.m. from Guillemont, to the west side of the wood and the troops in the wood were to attack south from the railway line, using flame-throwers to push the British out of the south end.[29] Part of Infantry Regiment 178 was to attack Maltz Horn Trench from Arrow Head Copse but the movement of troops near Guillemont was seen at 8:00 p.m. by the crew of a 9 Squadron aircraft, who also saw a German barrage fall between Bernafay and Trônes Wood and called for a counter-barrage.[30] The German infantry were scattered by the shelling, lost many casualties and the troops moving up for the attack on Maltz Horn Trench failed to reach their front line. The attack was abandoned and after dark, the survivors were sent to reinforce the troops in the wood. III Battalion, Reserve Infantry Regiment 106 arrived overnight and sent a company to the north-western edge.[29] The British 30th Division was relieved early on 13 July by the 18th (Eastern) Division, the 55th Brigade taking over at Maltz Horn Trench and Trônes Wood, ready to attack at 7:00 p.m.[31]

At 5:00 p.m. a British bombardment began, mainly on Longueval Alley and Central Trench. Troops in Maltz Horn Trench began to bomb north towards the strong point but only got to within 20 yd (18 m), despite several attempts up the trench and across the open. The battalion in the wood attacked north and lost direction again in the undergrowth and tangle of fallen trees, stumbling into the German posts along Central Trench and being engaged at close-range. Troops from Reserve Infantry Regiment 106 moved down from the north end of the wood to reinforce Central Trench as about 150 British troops reached the east edge of the wood, in the dark near the Guillemont track and under the impression that they were at the northern end of the wood; when dawn broke, attempts made to advance north failed. The left-hand battalion advanced across the open ground from Longueval Alley, into massed German machine-gun and artillery-fire, directed by observers on Longueval ridge despite a British gas barrage, preventing the British from getting closer than 100 yd (91 m) to the wood, except for small parties which were destroyed. Another British bombardment at 8:45 p.m. was ineffective and the survivors withdrew with their wounded, except for a platoon which had bombed along Longueval Alley and dug in at the apex of the wood. XIII Corps HQ received a report after midnight when the British general attack on 14 July was due to begin in three hours. The 18th (Eastern) Division commander Major-General Ivor Maxse ordered the 54th Brigade to attack before dawn, to take the eastern fringe as a flank guard, for the 9th Division attack on Longueval.[32]

14 July

Just after midnight on 13/14 July, the 54th Brigade began to assemble for another attack on the wood. With no time for reconnaissance and attacking in the dark, the commander Brigadier-General H. Shoubridge decided that the simplest plan was needed and ordered an advance from south to north, with a defensive flank along the eastern edge of the wood being formed during the attack. The two nearest battalions were ordered forward, with the commander of the 12th Middlesex Battalion, Lieutenant-Colonel F. A. Maxwell put in charge of the attack. By 2:30 a.m. one battalion was ready but the other one was still assembling. At 4:30 a.m., an hour after the main attack (the Battle of Bazentin Ridge) had begun, the leading battalion crossed 1,000 yd (910 m) of open ground in artillery formation through a German barrage, into the south-western side of the wood. The German redoubt at the south end of Central Trench was enveloped and rushed at 6:00 a.m., then the advance continued and reached the eastern edge, which was again mistaken for the northern point of the wood. A defensive flank was formed from the railway line, south to the strong point at Trônes Alley; the second battalion entered the wood at 8:00 a.m. and Maxwell went forward and found parties from many units in the south-eastern corner. No sounds of battle could be heard and a search to the north found little sign of the first battalion. Maxwell sent a company to attack the strong point, combined with another attack by the troops in Maltz Horn Trench.[33]

An officer moved west by compass and troops followed in single-file, then turned right to advance north. Direction continued to be maintained by compass, with frequent halts to reorganise and the troops fired into the undergrowth as they advanced. The south end of Central Trench was rolled up, threatening the German posts along the western edge with envelopment and the Germans withdrew north to the railway line. The last German survivors were ordered out at 9:00 a.m. and retired to Guillemont Station and Waterlot Farm.[34] The British reached the real northern point at 9:30 a.m., after a delay at the light railway to capture a machine-gun nest. German troops pushed north by the advance tried to retreat to Guillemont, covered by four machine-guns at the eastern edge but lost many casualties to British infantry fire from the defensive flank and the strong point, which had been taken at 9:00 a.m. Consolidation began by linking a line of shell-holes, which lay beyond the eastern fringe of the wood.[33] The German 24th Reserve Division from Champagne, had reached the Somme front on 14 July and Reserve Infantry Regiment 107 was ordered to retake Trônes Wood. At Guillemont the regiment was ordered to dig in from the village past the east end of Delville Wood. The signs of a German counter-attack were seen in the afternoon and a British bombardment of the east side of the wood continued into the night but no attack came, the German second line having been made the main line of defence.[35]

Aftermath

Analysis

Prior and Wilson counted eight British attacks on Trônes Wood and wrote that the first seven failed, because of machine-gun fire from the strong points along the railway through the wood, which were not captured until their positions became known. The Fourth Army corps had made 46 sporadic and piecemeal attacks in the period, with only an average of 14 percent of British battalions attacking each day. Artillery support was poorly co-ordinated, with guns of neighbouring corps not firing in support of attacks which were within range but German artillery and infantry was concentrated against small parts of the front, creating a great local density of shell and machine-gun fire. Despite these criticisms, Prior and Wilson wrote that the British advances from 2–14 June took 20 sq mi (52 km2), compared with 3 sq mi (7.8 km2) on 1 July. The German defence from Trônes Wood to La Boisselle, had become chaotic, as the British and French exploited the success gained south of the Albert–Bapaume road on 1 July. Elaborate German defensive positions had been overrun and much of the German artillery in the area had been destroyed. The German policy of unyielding defence, led to reinforcements being committed piecemeal as soon as they arrived and no reserve to make an organised counter-attack could be accumulated. Prior and Wilson called this practice as "inept" as British methods, compared to tactical withdrawals to shorten the line and create reserves. The equivalent British unrelenting attacks, led to poor planning and co-ordination, only succeeding because of the difficulties it imposed on the German defence (sic).[36]

Sheldon wrote that British artillery ammunition consumption would have restricted attacks after 1 July, even if the disaster north of the Albert–Bapaume road had not occurred. Limited local attacks south of the road were the only way to maintain pressure and support the French but took place on ground which had some defensive potential. British, French and German troops endured enormous strain, their discipline and endurance being tested "to the limit" and each crisis in the German defence merged with the next.[37] Philpott wrote that Haig underestimated the German reserves available by half but that they were in chaos, as Haig had believed and that by resorting to smaller attacks, Haig and Rawlinson had concentrated British artillery on smaller and shallower objectives, although this had led to piecemeal attacks which were easier to oppose. Falkenhayn's policy of unyielding defence condemned the German army to attrition, such as that experienced at Trônes Wood. The first British attack on the wood, was delayed by a German counter-attack on Bois Favière and French attacks had been stopped due to German fire from Trônes Wood, which took the British five more days to capture, exhausting the 30th Division in costly attacks, which were repulsed by well-placed machine-guns and frequent counter-attacks.[38]

Duffy wrote that after 1 July, German losses of ground were reduced, at Trônes Wood and other points but that a German divisional commander on 7 July reported that the crisis had been survived "for the time being". The German high command had known of the offensive due on the Somme but not the "weight and ferocity" of the attack. British historians write of the period 2–13 July, as a wasted opportunity, costing 25,000 casualties but not that the Germans had lost the initiative and were constantly off-balance. British infantry at Trônes Wood could assemble in captured German positions and move supplies along repaired German trenches in Bernafay Wood. Ground held nearby gave the British scope to outflank the wood from the north and south, who by using their many machine-guns skilfully, eventually took the wood in a "model operation".[39] Harris criticised the delegation of responsibility in the Fourth Army, blaming this for piecemeal attacks, not supported by all of the army artillery, against concentrated German artillery-fire. Multi-division attacks could take a week to prepare, a delay which would have been more help to the defence, than constant British attacks and German counter-attacks, which were even more hurried and disorganised than British efforts. Harris called the attack of 14 July on the XIII Corps front "possibly disastrous", because of the menace of German troops in Trônes Wood, to the 9th Division attack on Longueval.[40]

Casualties

When relieved on 5 July the 30th Division losses were 3,000 and when relieved again on 13 July the division had lost another 2,300 men.[41] By 8 July the 18th (Eastern) Division had lost 3,400 men, mostly wounded and the attack on 13/14 July cost another 1,527 casualties.[42][43] The 90th Brigade of the 18th (Eastern) Division had 789 casualties and German Infantry Regiment 182 lost 566 men by 12 July.[29]

Subsequent operations

By the beginning of the Battle of Bazentin Ridge (14–17 July) all the trees in Trônes Wood had been toppled, with only low stumps remaining. Tree trunks, barbed wire and human remains lay everywhere, the ground open and easily observed from German positions. Attacks from the wood on Guillemont began on 22/23 July, with various battalion headquarters sited in the wood. Later in the year the area was used for accommodation, Camp 34 being made up of groups of tarpaulin shelters.[44]

Commemoration

Memorials

At the south side of the wood near the road lies an obelisk of the 18th (Eastern) Division and several German dug-outs in the sunken road remained in 1985.[44]

Notes

- Bernafay Wood is on the north side of the D 64, Montauban–Guillemont road and east of the D 197, Maricourt–Longueval road, 300 m (330 yd) west of Trônes Wood. In 1916, it was in the area of the left of the 28th Reserve Division, the right of the 12th Division and Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment 6, from the 10th Bavarian Division.[5]

- Trônes Wood is pear-shaped, about 1,400 yd (1,300 m) long and 400 yd (370 m) wide along the base and lies east of Bernafay Wood, east of Montauban, south of Longueval and west of Guillemont. The light railway from Montauban to Guillemont ran through a dip in the centre of the wood. Undergrowth in the wood had not been cleared for two years, which made movement very difficult. Trônes Alley was a German communication trench, along Montauban ridge between the woods.[7]

- 33 German battalions had been engaged by then and 40 more were on the way.[9]

- The 123rd Division had been in Flanders as part of the 6th Army reserve and travelled from Thourout to Cambrai, disembarking at Épehy and Gouzeaucourt in the 2nd Army area on 6/7 July. The division was to mount a counter-attack from Hardecourt to Longueval but after seven days in the line, the Anglo-French attack on 8 July had exhausted the 12th Reserve Division and the 123rd Division was hurried forward to relieve it.[19] (British reconnaissance aircraft observed the German troop movements on the railways leading to the Somme and made bomb attacks on the trains and stations.)[20]

Footnotes

- Miles 1992, pp. 3–4.

- Philpott 2009, pp. 215.

- Simpson 2001, p. 59–61.

- Rogers 2010, pp. 79–80.

- Gliddon 1987, pp. 58–59.

- Miles 1992, pp. 17–18.

- Gliddon 1987, p. 397.

- Miles 1992, p. 23.

- Miles 1992, p. 24.

- Rogers 2010, p. 80.

- Miles 1992, pp. 45–47.

- Nichols 2004, pp. 52–55.

- Miles 1992, pp. 26–27.

- Miles 1992, pp. 60–61.

- Gliddon 1987, pp. 415–416.

- Rogers 2010, pp. 80–81.

- Philpott 2009, p. 230.

- Rogers 2010, p. 81.

- Rogers 2010, pp. 81–82.

- Jones 2002, p. 225.

- McCarthy 1995, p. 43.

- Rogers 2010, pp. 82–83.

- Rogers 2010, p. 83.

- Miles 1992, pp. 45–46.

- Rogers 2010, pp. 84–86.

- Miles 1992, pp. 46–47.

- Rogers 2010, pp. 86–87.

- Rogers 2010, pp. 87–89.

- Rogers 2010, p. 90.

- Jones 2002, p. 223.

- Miles 1992, pp. 47–48.

- Miles 1992, pp. 48–49.

- Miles 1992, pp. 75–78.

- Rogers 2010, pp. 91–92.

- Rogers 2010, p. 92.

- Prior & Wilson 2005, pp. 127–129.

- Sheldon 2006, pp. 184, 190.

- Philpott 2009, pp. 225, 230–231.

- Duffy 2007, pp. 172–173, 179.

- Harris 2009, p. 249.

- Miles 1992, p. 47.

- Miles 1992, pp. 21, 40.

- Nichols 2004, p. 69.

- Gliddon 1987, pp. 401–404.

References

- Duffy, C. (2007) [2006]. Through German Eyes: The British and the Somme 1916 (Phoenix ed.). London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-7538-2202-9.

- Gliddon, G. (1987). When the Barrage Lifts: A Topographical History and Commentary on the Battle of the Somme 1916. Norwich: Gliddon Books. ISBN 978-0-947893-02-6.

- Harris, J. P. (2009) [2008]. Douglas Haig and the First World War (repr. ed.). Cambridge: CUP. ISBN 978-0-521-89802-7.

- Jones, H. A. (2002) [1928]. The War in the Air, Being the Story of the Part Played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force. II (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-1-84342-413-0. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- McCarthy, C. (1995) [1993]. The Somme: The Day-by-Day Account (Arms & Armour Press ed.). London: Weidenfeld Military. ISBN 978-1-85409-330-1.

- Miles, W. (1992) [1938]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916: 2nd July 1916 to the End of the Battles of the Somme. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. II (Imperial War Museum & Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-901627-76-6.

- Nichols, G. H. F. (2004) [1922]. The 18th Division in the Great War (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Blackwood. ISBN 978-1-84342-866-4.

- Philpott, W. (2009). Bloody Victory: The Sacrifice on the Somme and the Making of the Twentieth Century. London: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-1-4087-0108-9.

- Prior, R.; Wilson, W. (2005). The Somme. London: Yale. ISBN 978-0-300-10694-7 – via Archive Foundation.

- Rogers, D., ed. (2010). Landrecies to Cambrai: Case Studies of German Offensive and Defensive Operations on the Western Front 1914–17. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-906033-76-7.

- Sheldon, J. (2006) [2005]. The German Army on the Somme 1914–1916 (Pen & Sword Military ed.). London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 978-1-84415-269-8.

Theses

- Simpson, Andrew (2001). The Operational Role of British Corps Command on the Western Front 1914–18. discovery.ucl.ac.uk (PhD thesis). London: University of London. OCLC 53564367. EThOS uk.bl.ethos.367588. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

Further reading

- Buchan, J. (1992) [1920]. The History of the South African Forces in France (Imperial War Museum & Battery Press ed.). London: Thomas Nelson. ISBN 978-0-901627-89-6. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- Ewing, J. (2001) [1921]. The History of the Ninth (Scottish) Division 1914–1919 (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: John Murray. ISBN 978-1-84342-190-0. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- Rowan, E. W. J. (1919). The 54th Infantry Brigade, 1914–1918; Some Records of Battle and Laughter in France. London: Gale & Polden. OCLC 37599956. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- Sheffield, G. (2011). The Chief: Douglas Haig and the British Army. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-84513-691-8.