Subramania Bharati

Subramania Bharathi (11 December 1882 – 11 September 1921), was a Tamil writer, poet, journalist, Indian independence activist, social reformer and polyglot. Popularly known as "Mahakavi Bharathi" ("Great Poet Bharathi"), he was a pioneer of modern Tamil poetry and is considered one of the greatest Tamil literary figures of all time. His numerous works included fiery songs kindling patriotism during the Indian Independence movement.[1][2] He fought for the emancipation of women, against child marriage, stood for reforming Brahminism and religion. He was also in solidarity with Dalits and Muslims.[3][4]

Subramania Bharathi | |

|---|---|

சுப்பிரமணிய பாரதி | |

Subramania Bharathi Commemorative Stamp | |

| Born | 11 December 1882 |

| Died | 12 September 1921 (aged 38) |

| Other names | Bharathi, Subbaiah, Sakthi Dasan, Mahakavi, Mundasu Kavignar, Veera Kavi, Selly Dasan |

| Citizenship | British Raj |

| Occupation | Journalist, poet, writer, teacher, patriot, freedom fighter |

| Movement | Indian independence movement |

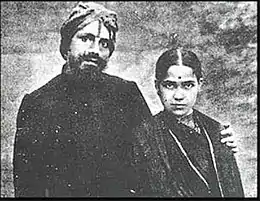

| Spouse(s) | Chellamma/Kannamma (m. 1896–1921) |

| Children | 2 |

| Signature | |

Born in Ettayapuram of Tirunelveli district (present day Thoothukudi) in 1882, Bharathi had his early education in Tirunelveli and Varanasi and worked as a journalist with many newspapers, including The Hindu, Bala Bharata, Vijaya, Chakravarthini, the Swadesamitran and India. In 1908, an arrest warrant was issued against Bharati by the government of British India caused him to move to Pondicherry where he lived until 1918.[5]

Bharathi's influence on Tamil literature is phenomenal. Although it is said that he was proficient in around 14, including 3 non-Indian foreign languages. His favorite language was Tamil. He was prolific in his output. He covered political, social and spiritual themes. The songs and poems composed by Bharati are very often used in Tamil cinema and have become staples in the literary and musical repertoire of Tamil artistes throughout the world. He paved the way for modern blank verse. He wrote many books and poems on how Tamil is beautiful in nature.

Biography

Bharati was born on 11 December 1882 in the village of Ettayapuram, to Chinnaswami Subramania Iyer and Lakshmi Ammal. Subbaiah, as he was named, went to the M.D.T. Hindu College in Tirunelveli. From a very young age, he was musically and poetically inclined. Bharati lost his mother at the age of five and was brought up by his father who wanted him to learn English, excel in arithmetic, and become an engineer.[6][7] A proficient linguist, he was well-versed in Sanskrit, Hindi, Telugu, English, French and had a smattering of Arabic. Around the age of 11, he was conferred the title of "Bharati", the one blessed by Saraswati, the goddess of learning. He lost his father at the age of sixteen, but before that when he was 10, he married Chellamma who was seven years old.

During his stay in Varanasi, Bharati was exposed to Hindu spirituality and nationalism. This broadened his outlook and he learned Sanskrit, Hindi and English. In addition, he changed his outward appearance. He also grew a beard and wore a turban due to his admiration of Sikhs, influenced by his Sikh friend. Though he passed an entrance exam for a job, he returned to Ettayapuram during 1901 and started as the court poet of Raja of Ettayapuram for a couple of years. He was a Tamil teacher from August to November 1904 in Sethupathy High School in Madurai.[7] During this period, Bharati understood the need to be well-informed of the world outside and took interest in the world of journalism and the print media of the West. Bharati joined as Assistant Editor of the Swadesamitran, a Tamil daily in 1904. In December 1905, he attended the All India Congress session held in Benaras. On his journey back home, he met Sister Nivedita, Swami Vivekananda's spiritual heir. She inspired Bharati to recognise the privileges of women and the emancipation of women exercised Bharati's mind. He visualised the new woman as an emanation of Shakti, a willing helpmate of man to build a new earth through co-operative endeavour. Among other greats such as Bal Gangadhar Tilak, he considered Nivedita as his Guru, and penned verses in her praise. He attended the Indian National Congress session in Calcutta under Dadabhai Naoiroji, which demanded Swaraj and boycott of British goods.[7]

By April 1906, he started editing the Tamil weekly India and the English newspaper Bala Bharatham with M.P.T. Acharya. These newspapers were also a means of expressing Bharati's creativity, which began to peak during this period. Bharati started to publish his poems regularly in these editions. From hymns to nationalistic writings, from contemplations on the relationship between God and Man to songs on the Russian and French revolutions, Bharati's subjects were diverse.[6]

Bharati participated in the historic Surat Congress in 1907 along with V.O. Chidambaram Pillai and Mandayam Srinivachariar, which deepened the divisions within the Indian National Congress with a section preferring armed resistance, primarily led by Tilak over moderate approach preferred by certain other sections. Bharati supported Tilak with V. O. Chidambaram Pillai and Kanchi Varathachariyar. Tilak openly supported armed resistance against the British.[7]

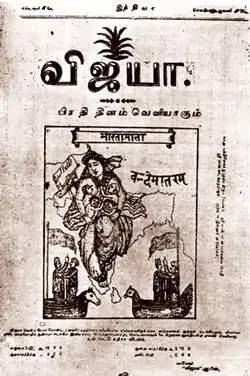

In 1908, the British instituted a case against V.O. Chidambaram Pillai. In the same year, the proprietor of the journal India was arrested in Madras. Faced with the prospect of arrest, Bharati escaped to Pondicherry, which was under French rule.[8] From there he edited and published the weekly journal India, Vijaya, a Tamil daily, Bala Bharatham, an English monthly, and Suryodayam, a local weekly in Pondicherry. The British tried to suppress Bharati's output by stopping remittances and letters to the papers. Both India and Vijaya were banned in India in 1909.[7]

During his exile, Bharati had the opportunity to meet many other leaders of the revolutionary wing of the Independence movement like Aurobindo, Lajpat Rai and V.V.S. Aiyar, who had also sought asylum under the French. Bharati assisted Aurobindo in the Arya journal and later Karma Yogi in Pondicherry.[6] This was also the period when he started learning Vedic literature. Three of his greatest works namely, Kuyil Pattu, Panchali Sapatham and Kannan Pattu were composed during 1912. He also translated Vedic hymns, Patanjali's Yoga Sutra and Bhagavat Gita to Tamil.[7] Bharati entered India near Cuddalore in November 1918 and was promptly arrested. He was imprisoned in the Central prison in Cuddalore in custody for three weeks from 20 November to 14 December and was released after the intervention of Annie Besant and C.P. Ramaswamy Aiyar. He was stricken by poverty during this period, resulting in his ill health. The following year, 1919, Bharati met Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. He resumed editing Swadesimeitran from 1920 in Madras (modern day Chennai).[9]

Death

He was badly affected by the imprisonments and by 1920, when a General Amnesty Order finally removed restrictions on his movements, Bharati was already struggling. He was struck by an elephant named Lavanya at Parthasarathy temple, Triplicane, Chennai, whom he used to feed regularly. When he fed a spoilt coconut to Lavanya (the elephant), the elephant got fired up and attacked Bharati. Although he survived the incident, his health deteriorated a few months later and he died early morning on 11 September 1921 at around 1 am. Though Bharati was considered a people's poet, a great nationalist, outstanding freedom fighter and social visionary, it was recorded that there were only 14 people to attend his funeral. He delivered his last speech at Karungalpalayam Library in Erode, which was about the topic Man is Immortal.[10] The last years of his life were spent in a house in Triplicane, Chennai. The house was bought and renovated by the Government of Tamil Nadu in 1993 and named Bharati Illam (Home of Bharati).

Works

Bharati is considered as one of the pioneers of modern Tamil literature.[12] Bharati used simple words and rhythms, unlike his previous century works in Tamil, which had complex vocabulary. He also employed novel ideas and techniques in his devotional poems.[1] He used a metre called Nondi Chindu in most of his works, which was earlier used by Gopalakrisnha Bharathiar.[13]

Bharati's poetry expressed a progressive, reformist ideal. His imagery and the vigour of his verse were a forerunner to modern Tamil poetry in different aspects. He was the forerunner of a forceful kind of poetry that combined classical and contemporary elements. He had a prodigious output penning thousands of verses on diverse topics like Indian Nationalism, love songs, children's songs, songs of nature, glory of the Tamil language, and odes to prominent freedom fighters of India like Tilak, Gandhi and Lajpat Rai. He even penned an ode to New Russia and Belgium. His poetry not only includes works on Hindu deities like Shakti, Kali, Vinayagar, Murugan, Sivan, Kannan(Krishna), but also on other religious gods like Allah and Jesus. His insightful similes have been read by millions of Tamil readers. He was well-versed in various languages and translated speeches of Indian National reform leaders like Sri Aurobindo, Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Swami Vivekananda.[9]

He describes the dance of Shakthi (in Oozhi koothu, Dance of destiny) in the following lines:

Tamil | |

It is the opinion of some litterateurs that Bharathiar's Panchali Sapatham, based on the story of Panchali (Draupadi), is also an ode to Bharat Mata. That the Pandavass are the Indians, the Kauravas the British and the Kurukshetra war of Mahabharat that of the Indian freedom struggle. It certainly is ascribed to the rise of womanhood in society.[6][7]

Tamil |

[English Translation] |

He is known to have said, "Even if Indians are divided, they are children of one Mother, where is the need for foreigners to interfere?" In the period 1910–1920, he wrote about a new and free India where there are no castes. He talks of building up India's defense, her ships sailing the high seas, success in manufacturing and universal education. He calls for sharing amongst states with wonderful imagery like the diversion of excess water of the Bengal delta to needy regions and a bridge to Sri Lanka.

Bharati also wanted to abolish starvation. He sang, "Thani oru manithanakku unavu illayenil intha jagaththinai azhithiduvom" translated as " If one single man suffers from starvation, we will destroy the entire world".

Some of his poems are translated by Jayanthasri Balakrishnan in English in her blog, though not published.[14]

Even though he has strong opinions about Gods, he is also against false stories spread in epics and other part of social fabric in Tamil Nadu.

In Kuyil paattu (Song of Nightingale) (குயில் பாட்டு) he writes..

| கடலினைத் தாவும் குரவும்-வெங்

கனலிற் பிறந்ததோர் செவ்விதழ்ப் பெண்ணும், வடமலை தாழ்ந்தத னாலே-தெற்கில் வந்து சமன்செயும் குட்டை முனியும், நதியி னுள்ளேமுழு கிப்போய்-அந்த நாகர் உலகிலோர் பாம்பின் மகளை விதியுற வேமணம் செய்த-திறல் வீமனும் கற்பனை என்பது கண்டோம். ஒன்றுமற் றொன்றைப் பழிக்கும்-ஒன்றில் உண்மையென் றோதிமற் றொன்றுபொய் யென்னும் நன்று புராணங்கள் செய்தார்-அதில் நல்ல கவிதை பலபல தந்தார். கவிதை மிகநல்ல தேனும்-அக் கதைகள் பொய்யென்று தெளிவுறக் கண்டோம்; |

Monkey that jumps the seas;

Woman who born inside the hot fire; The sage who came to south to equalize because of lowered; The man called Bhima who submerged and swim inside the river and married the daughter of serpent king of fate; We have seen all those are just imagination.. One blame the other; And say the truth is only here, and other is lie; They made good epic, with that They gave good poems; Even though the poems are good; We saw clearly that those stories are lies; |

Bharati on caste system

Bharati also fought against the caste system in Hindu society. Bharathi was born in an orthodox Brahmin family, but he considered all living beings as equal and to illustrate this he performed the upanayanam for a young Dalit man and made him a Brahmin. He also scorned the divisive tendencies being imparted into the younger generations by their elderly tutors during his time. He openly criticised the preachers for mixing their individual thoughts while teaching the Vedas, Upanishads and the Gita. He strongly advocated bringing the Dalits to the Hindu mainstream.

Tamil |

[English Translation] |

Legacy

The Government of India in 1987 instituted a highest National Subramanyam Bharti Award conferred along with Ministry of Human Resource Development, annually confers on writers of outstanding works in Hindi literature.

Bharathiar University, a state university named after the poet, was established in 1982 at Coimbatore.[15] There is a statue of Bharathiar at Marina Beach and also in the Indian Parliament. A Tamil Movie titled Bharati was made in the year 2000 on the life of the poet by Gnana Rajasekeran, which won National Film Award for Best Feature Film in Tamil.[16] The movie Kappalottiya Thamizhan chronicles the important struggles of V.O.Chidambaranar along with Subramanya Siva and Bharathiar with S.V. Subbaiah starring as Subramania Bharati. On 14 August 2014 Professor Muhammadu Sathik raja Started an Educational trust at thiruppuvanam pudur, near Madurai named as Omar -Bharathi educational trust, the name is kept to praise the two legendary poets Umaru Pulavar and Subramania Bharathiyar from Ettaiyapuram. Though these two Poets are having three centuries time interval, the divine service and their contribution to the Tamil language are made them unparallel legends. Both two poets are offered their services at vaigai river bank of thiruppuvanam. the two poets were strongly suffered by their financial status, so both of them were unsuccessful to fulfil their family members need. Many roads are named after him, notable ones including Bharathiar road in Coimbatore and Subramaniam Bharti Marg in New Delhi.[17][18] The NGO Sevalaya runs the Mahakavi Bharatiya Higher Secondary School.[19]

See also

References

- Natarajan, Nalini; Nelson, Emmanuel Sampath, eds. (1996). Handbook of Twentieth-century Literatures of India. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 290. ISBN 9780313287787.

- "Congress Veteran reenacts Bharathis escape to Pondy". The Times of India.

- "Knowing Subramania Bharati beyond his turban colour". www.telegraphindia.com. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- Raman, Aroon (21 December 2009). "All too human at the core". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- "On the streets where Bharati walked". The Hindu.

- Indian Literature: An Introduction. University of Delhi. Pearson Education India. 2005. pp. 125–126. ISBN 9788131705209.

- Bharati, Subramania; Rajagopalan, Usha (2013). Panchali's Pledge. Hachette UK. p. 1. ISBN 9789350095300.

- "Bharati's Tamil daily Vijaya traced in Paris". The Hindu. 5 December 2004.

- Lal, Mohan (1992). Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: sasay to zorgot. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 4191–3. ISBN 9788126012213.

- "Last speech delivered in Erode". The Hindu. 15 April 2008. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- "Brief Shining Moment in Judicial History". Daily News. Colombo, Sri Lanka. 11 June 2013. Archived from the original on 10 June 2014. Retrieved 30 November 2013. – via HighBeam (subscription required)

- Annamalai, E. (1968). "Changing society and modern Tamil literature". Tamil Issue. 4 (3/4): 21–36. JSTOR 40874190.(subscription required)

- George, K.M., ed. (1992). Modern Indian Literature, an Anthology: Plays and prose. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi. p. 379. ISBN 978-81-7201-324-0.

- "Jayanthasri translations". mythreyid.academia.edu. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- Gupta, Ameeta; Kumar, Ashish (2006). Handbook of Universities, Volume 1. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. p. 14. ISBN 9788126906079.

- "SA women 'swoon' over Sanjay". Sunday Tribune. South Africa. 30 March 2008. Archived from the original on 10 June 2014. Retrieved 30 November 2013. – via HighBeam (subscription required)

- "Free helmet distribution". The Times of India. 6 October 2015.

- "Subramaniam Bharti Marg". Indian Express. 3 October 2015.

- "Activities: School". Sevalaya.

Further reading

- Fire In The Soul: The Life And Times of Subramania Bharati. OCLC 339.

- “Subramania Barati and Tamil Modernism”

- "Fictionalizing an Untold History"

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Subramanya Bharathi. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Subramania Bharati |

- Mahakavi Subramania Bharati by Bharati's Granddaughter, Dr. S. Vijaya Bharati

- To know all about Mahakavi Bharathiar

- Complete history of Mahakavi Bharathiar

- http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-national/tp-tamilnadu/Bharathiar-museum-in-Cuddalore-prison-to-be-thrown-open-soon/article16630552.ece

- Works by Subramania Bharati at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)