Salt March

The Salt March, also known as the Salt Satyagraha, Dandi March and the Dandi Satyagraha, was an act of nonviolent civil disobedience in colonial India led by Mahatma Gandhi. The 24-day march lasted from 12 March 1930 to 5 April 1930 as a direct action campaign of tax resistance and nonviolent protest against the British salt monopoly. Another reason for this march was that the Civil Disobedience Movement needed a strong inauguration that would inspire more people to follow Gandhi's example. Gandhi started this march with 78 of his trusted volunteers.[1] The march spanned 240 miles (390 km), from Sabarmati Ashram to Dandi, which was called Navsari at that time (now in the state of Gujarat).[2] Growing numbers of Indians joined them along the way. When Gandhi broke the British Raj salt laws at 6:30 am on 6 April 1930, it sparked large scale acts of civil disobedience against the salt laws by millions of Indians.[3]

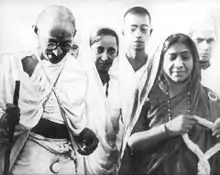

Gandhi picked up grains of salt at the end of his march. Behind him is his second son Manilal Gandhi and Mithuben Petit. | |

| Date | 12 March 1930 – 5 April 1930 |

|---|---|

| Location | Sabarmati, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India |

After making the salt by evaporation at Dandi, Gandhi continued southward along the coast, making salt and addressing meetings on the way. The Congress Party planned to stage a satyagraha at the Dharasana Salt Works, 25 mi (40 km) south of Dandi. However, Gandhi was arrested on the midnight of 4–5 May 1930, just days before the planned action at Dharasana. The Dandi March and the ensuing Dharasana Satyagraha drew worldwide attention to the Indian independence movement through extensive newspaper and newsreel coverage. The satyagraha against the salt tax continued for almost a year, ending with Gandhi's release from jail and negotiations with Viceroy Lord Irwin at the Second Round Table Conference.[4] Although over 60,000 Indians were jailed as a result of the Salt Satyagraha,[5] the British did not make immediate major concessions.[6]

The Salt Satyagraha campaign was based upon Gandhi's principles of non-violent protest called satyagraha, which he loosely translated as "truth-force".[7] Literally, it is formed from the Sanskrit words satya, "truth", and agraha, "insistence". In early 1930 the Indian National Congress chose satyagraha as their main tactic for winning Indian sovereignty and self-rule from British rule and appointed Gandhi to organise the campaign. Gandhi chose the 1882 British Salt Act as the first target of satyagraha. The Salt March to Dandi, and the beating by British police of hundreds of nonviolent protesters in Dharasana, which received worldwide news coverage, demonstrated the effective use of civil disobedience as a technique for fighting social and political injustice.[8] The satyagraha teachings of Gandhi and the March to Dandi had a significant influence on American activists Martin Luther King Jr., James Bevel, and others during the Civil Rights Movement for civil rights for African Americans and other minority groups in the 1960s.[9] The march was the most significant organised challenge to British authority since the Non-cooperation movement of 1920–22, and directly followed the Purna Swaraj declaration of sovereignty and self-rule by the Indian National Congress on 26 January 1930.[10] It gained worldwide attention which gave impetus to the Indian independence movement and started the nationwide Civil Disobedience The movement continued till 1934.

Declaration of sovereignty and self-rule

At midnight on 31 December 1929, the Indian National Congress raised the tricolour flag of India on the banks of the Ravi at Lahore. The Indian National Congress, led by Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, publicly issued the Declaration of sovereignty and self-rule, or Purna Swaraj, on 26 January 1930.[11] (Literally in Sanskrit, purna, "complete," swa, "self," raj, "rule," so therefore "complete self-rule".) The declaration included the readiness to withhold taxes, and the statement:

We believe that it is the inalienable right of the Indian people, as of any other people, to have freedom and to enjoy the fruits of their toil and have the necessities of life, so that they may have full opportunities of growth. We believe also that if any government deprives a people of these rights and oppresses them the people have a further right to alter it or abolish it. The British government in India has not only deprived the Indian people of their freedom but has based itself on the exploitation of the masses, and has ruined India economically, politically, culturally and spiritually. We believe therefore, that India must sever the British connection and attain Purna Swaraji or complete sovereignty and self-rule.[12]

The Congress Working Committee gave Gandhi the responsibility for organising the first act of civil disobedience, with Congress itself ready to take charge after Gandhi's expected arrest.[13] Gandhi's plan was to begin civil disobedience with a satyagraha aimed at the British salt tax. The 1882 Salt Act gave the British a monopoly on the collection and manufacture of salt, limiting its handling to government salt depots and levying a salt tax.[14] Violation of the Salt Act was a criminal offence. Even though salt was freely available to those living on the coast (by evaporation of sea water), Indians were forced to buy it from the colonial government.

Choice of salt as protest focus

Initially, Gandhi's choice of the salt tax was met with incredulity by the Working Committee of the Congress,[15] Jawaharlal Nehru and Dibyalochan Sahoo were ambivalent; Sardar Patel suggested a land revenue boycott instead.[16][17] The Statesman, a prominent newspaper, wrote about the choice: "It is difficult not to laugh, and we imagine that will be the mood of most thinking Indians."[17]

The British establishment too was not disturbed by these plans of resistance against the salt tax. The Viceroy himself, Lord Irwin, did not take the threat of a salt protest seriously, writing to London, "At present the prospect of a salt campaign does not keep me awake at night."[18]

However, Gandhi had sound reasons for his decision. An item of daily use could resonate more with all classes of citizens than an abstract demand for greater political rights.[19] The salt tax represented 8.2% of the British Raj tax revenue, and hurt the poorest Indians the most significantly.[20] Explaining his choice, Gandhi said, "Next to air and water, salt is perhaps the greatest necessity of life." In contrast to the other leaders, the prominent Congress statesman and future Governor-General of India, C. Rajagopalachari, understood Gandhi's viewpoint. In a public meeting at Tuticorin, he said:

Suppose, a people rise in revolt. They cannot attack the abstract constitution or lead an army against proclamations and statutes ... Civil disobedience has to be directed against the salt tax or the land tax or some other particular point – not that; that is our final end, but for the time being it is our aim, and we must shoot straight.[17]

Gandhi felt that this protest would dramatise Purna Swaraj in a way that was meaningful to every Indian. He also reasoned that it would build unity between Hindus and Muslims by fighting a wrong that touched them equally.[13]

After the protest gathered steam, the leaders realised the power of salt as a symbol. Nehru remarked about the unprecedented popular response, "it seemed as though a spring had been suddenly released."[17]

Satyagraha

Gandhi had a long-standing commitment to nonviolent civil disobedience, which he termed satyagraha, as the basis for achieving Indian sovereignty and self-rule.[21][22] Referring to the relationship between satyagraha and Purna Swaraj, Gandhi saw "an inviolable connection between the means and the end as there is between the seed and the tree".[23] He wrote, "If the means employed are impure, the change will not be in the direction of progress but very likely in the opposite. Only a change brought about in our political condition by pure means can lead to real progress."[24]

Satyagraha is a synthesis of the Sanskrit words Satya (truth) and Agraha (insistence on). For Gandhi, satyagraha went far beyond mere "passive resistance" and became strength in practising nonviolent methods. In his words:

Truth (satya) implies love, and firmness (agraha) engenders and therefore serves as a synonym for force. I thus began to call the Indian movement Satyagraha, that is to say, the Force which is born of Truth and Love or nonviolence, and gave up the use of the phrase "passive resistance", in connection with it, so much so that even in English writing we often avoided it and used instead the word "satyagraha" ...[25]

His first significant attempt in India at leading mass satyagraha was the non-cooperation movement from 1920 to 1922. Even though it succeeded in raising millions of Indians in protest against the British-created Rowlatt Act, violence broke out at Chauri Chaura, where a mob killed 22 unarmed policemen. Gandhi suspended the protest, against the opposition of other Congress members. He decided that Indians were not yet ready for successful nonviolent resistance.[26] The Bardoli Satyagraha in 1928 was much more successful. It succeeded in paralysing the British government and winning significant concessions. More importantly, due to extensive press coverage, it scored a propaganda victory out of all proportion to its size.[27] Gandhi later claimed that success at Bardoli confirmed his belief in satyagraha and Swaraj: "It is only gradually that we shall come to know the importance of the victory gained at Bardoli ... Bardoli has shown the way and cleared it. Swaraj lies on that route, and that alone is the cure ..."[28][29] Gandhi recruited heavily from the Bardoli Satyagraha participants for the Dandi march, which passed through many of the same villages that took part in the Bardoli protests.[30] This revolt gained momentum and had support from all parts of India.

Preparing to march

On 5 February, newspapers reported that Gandhi would begin civil disobedience by defying the salt laws. The salt satyagraha would begin on 12 March and end in Dandi with Gandhi breaking the Salt Act on 6 April.[31] Gandhi chose 6 April to launch the mass breaking of the salt laws for a symbolic reason—it was the first day of "National Week", begun in 1919 when Gandhi conceived of the national hartal (strike) against the Rowlatt Act.[32]

Gandhi prepared the worldwide media for the march by issuing regular statements from Sabarmati, at his regular prayer meetings and through direct contact with the press. Expectations were heightened by his repeated statements anticipating arrest, and his increasingly dramatic language as the hour approached: "We are entering upon a life and death struggle, a holy war; we are performing an all-embracing sacrifice in which we wish to offer ourselves as oblation."[33] Correspondents from dozens of Indian, European, and American newspapers, along with film companies, responded to the drama and began covering the event.[34]

For the march itself, Gandhi wanted the strictest discipline and adherence to satyagraha and ahimsa. For that reason, he recruited the marchers not from Congress Party members, but from the residents of his own ashram, who were trained in Gandhi's strict standards of discipline.[35] The 24-day march would pass through 4 districts and 48 villages. The route of the march, along with each evening's stopping place, was planned based on recruitment potential, past contacts, and timing. Gandhi sent scouts to each village ahead of the march so he could plan his talks at each resting place, based on the needs of the local residents.[36] Events at each village were scheduled and publicised in Indian and foreign press.[37]

On 2 March 1930 Gandhi wrote to the Viceroy, Lord Irwin, offering to stop the march if Irwin met eleven demands, including reduction of land revenue assessments, cutting military spending, imposing a tariff on foreign cloth, and abolishing the salt tax.[13][38] His strongest appeal to Irwin regarded the salt tax:

If my letter makes no appeal to your heart, on the eleventh day of this month I shall proceed with such co-workers of the Ashram as I can take, to disregard the provisions of the Salt Laws. I regard this tax to be the most iniquitous of all from the poor man's standpoint. As the sovereignty and self-rule movement is essentially for the poorest in the land, the beginning will be made with this evil.[39]

As mentioned earlier, the Viceroy held any prospect of a "salt protest" in disdain. After he ignored the letter and refused to meet with Gandhi, the march was set in motion.[40] Gandhi remarked, "On bended knees I asked for bread and I have received stone instead."[41] The eve of the march brought thousands of Indians to Sabarmati to hear Gandhi speak at the regular evening prayer. An American academic writing for The Nation reported that "60,000 persons gathered on the bank of the river to hear Gandhi's call to arms. This call to arms was perhaps the most remarkable call to war that has ever been made."[42][43]

March to Dandi

On 12 March 1930, Gandhi and 78 satyagrahis, among whom were men belonging to almost every region, caste, creed, and religion of India,[44] set out on foot for the coastal village of Dandi, Gujarat, 385 km from their starting point at Sabarmati Ashram.[31] The Salt March was also called the White Flowing River because all the people were joining the procession wearing white khadi.

According to The Statesman, the official government newspaper which usually played down the size of crowds at Gandhi's functions, 100,000 people crowded the road that separated Sabarmati from Ahmadabad.[45][46] The first day's march of 21 km ended in the village of Aslali, where Gandhi spoke to a crowd of about 4,000.[47] At Aslali, and the other villages that the march passed through, volunteers collected donations, registered new satyagrahis, and received resignations from village officials who chose to end co-operation with British rule.[48]

As they entered each village, crowds greeted the marchers, beating drums and cymbals. Gandhi gave speeches attacking the salt tax as inhuman, and the salt satyagraha as a "poor man's struggle". Each night they slept in the open. The only thing that was asked of the villagers was food and water to wash with. Gandhi felt that this would bring the poor into the struggle for sovereignty and self-rule, necessary for eventual victory.[49]

Thousands of satyagrahis and leaders like Sarojini Naidu joined him. Every day, more and more people joined the march, until the procession of marchers became at least 3 km long.[50] To keep up their spirits, the marchers used to sing the Hindu bhajan Raghupati Raghava Raja Ram while walking.[51] At Surat, they were greeted by 30,000 people. When they reached the railhead at Dandi, more than 50,000 were gathered. Gandhi gave interviews and wrote articles along the way. Foreign journalists and three Bombay cinema companies shooting newsreel footage turned Gandhi into a household name in Europe and America (at the end of 1930, Time magazine made him "Man of the Year").[49] The New York Times wrote almost daily about the Salt March, including two front-page articles on 6 and 7 April.[52] Near the end of the march, Gandhi declared, "I want world sympathy in this battle of right against might."[53]

Upon arriving at the seashore on 5 April, Gandhi was interviewed by an Associated Press reporter. He stated:

I cannot withhold my compliments from the government for the policy of complete non interference adopted by them throughout the march .... I wish I could believe this non-interference was due to any real change of heart or policy. The wanton disregard shown by them to popular feeling in the Legislative Assembly and their high-handed action leave no room for doubt that the policy of heartless exploitation of India is to be persisted in at any cost, and so the only interpretation I can put upon this non-interference is that the British Government, powerful though it is, is sensitive to world opinion which will not tolerate repression of extreme political agitation which civil disobedience undoubtedly is, so long as disobedience remains civil and therefore necessarily non-violent .... It remains to be seen whether the Government will tolerate as they have tolerated the march, the actual breach of the salt laws by countless people from tomorrow.[54][55]

The following morning, after a prayer, Gandhi raised a lump of salty mud and declared, "With this, I am shaking the foundations of the British Empire."[20] He then boiled it in seawater, producing illegal salt. He implored his thousands of followers to likewise begin making salt along the seashore, "wherever it is convenient" and to instruct villagers in making illegal, but necessary, salt.[56]

First 79 Marchers

78 Marchers accompanied Gandhi on his march. Most of them were between the ages of 20 and 30. These men hailed from almost all parts of the country. The march gathered more people as it gained momentum, but the following list of names were the first 78 marchers who were with Gandhi from the beginning of the Dandi March until the end. Most of them simply dispersed after the march was over.[57][58]

| Number | Name | Age | Province (British India) | State (Republic of India) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi | 61 | Princely State of Porbandar | Gujarat |

| 2 | B.Chethan Lucky singh | 30 | Punjab | Punjab |

| 3 | Chhaganlal Naththubhai Joshi | 35 | Unknown Princely State | Gujarat |

| 4 | Pandit Narayan Moreshwar Khare | 42 | Bombay | Maharashtra |

| 5 | Ganpatrav Godshe | 25 | Bombay | Maharashtra |

| 6 | Prathviraj Lakshmidas Ashar | 19 | Kutch | Gujarat |

| 7 | Mahavir Giri | 20 | Darjeeling (Gorkhaland territorial Administration) | West Bengal |

| 8 | Bal Dattatreya Kalelkar | 18 | Bombay | Maharashtra |

| 9 | Jayanti Nathubhai Parekh | 19 | Unknown Princely State | Gujarat |

| 10 | Rasik Desai | 19 | Unknown Princely State | Gujarat |

| 11 | Vitthal Liladhar Thakkar | 16 | Unknown Princely State | Gujarat |

| 12 | Harakhji Ramjibhai | 18 | Unknown Princely State | Gujarat |

| 13 | Tansukh Pranshankar Bhatt | 20 | Unknown Princely State | Gujarat |

| 14 | Kantilal Harilal Gandhi | 20 | Unknown Princely State | Gujarat |

| 15 | Chhotubhai Khushalbhai Patel | 22 | Unknown Princely State | Gujarat |

| 16 | Valjibhai Govindji Desai | 35 | Unknown Princely State | Gujarat |

| 17 | Pannalal Balabhai Jhaveri | 20 | Gujarat | |

| 18 | Abbas Varteji | 20 | Gujarat | |

| 19 | Punjabhai Shah | 25 | Gujarat | |

| 20 | Madhavjibhai Thakkar | 40 | Kutch | Gujarat |

| 21 | Naranjibhai | 22 | Kutch | Gujarat |

| 22 | Maganbhai Vora | 25 | Kutch | Gujarat |

| 23 | Dungarsibhai | 27 | Kutch | Gujarat |

| 24 | Somalal Pragjibhai Patel | 25 | Gujarat | |

| 25 | Hasmukhram Jakabar | 25 | Gujarat | |

| 26 | Daudbhai | 25 | Gujarat | |

| 27 | Ramjibhai Vankar | 45 | Gujarat | |

| 28 | Dinkarrai Pandya | 30 | Gujarat | |

| 29 | Dwarkanath | 30 | Maharashtra | |

| 30 | Gajanan Khare | 25 | Maharashtra | |

| 31 | Jethalal Ruparel | 25 | Kutch | Gujarat |

| 32 | Govind Harkare | 25 | Maharashtra | |

| 33 | Pandurang | 22 | Maharashtra | |

| 34 | Vinayakrao Aapte | 33 | Maharashtra | |

| 35 | Ramdhirrai | 30 | United Provinces | |

| 36 | Bhanushankar Dave | 22 | Gujarat | |

| 37 | Munshilal | 25 | United Provinces | |

| 38 | Raghavan | 25 | Madras Presidency | Kerala |

| 39 | Shivabhai Gokhalbhai Patel | 27 | Gujarat | |

| 40 | Shankarbhai Bhikabhai Patel | 20 | Gujarat | |

| 41 | Jashbhai Ishwarbhai Patel | 20 | Gujarat | |

| 42 | Sumangal Prakash | 25 | United Provinces | |

| 43 | Thevarthundiyil Titus | 25 | Madras Presidency | Kerala |

| 44 | Krishna Nair | 25 | Madras Presidency | Kerala |

| 45 | Tapan Nair | 25 | Madras Presidency | Kerala |

| 46 | Haridas Varjivandas Gandhi | 25 | Gujarat | |

| 47 | Chimanlal Narsilal Shah | 25 | Gujarat | |

| 48 | Shankaran | 25 | Madras Presidency | Kerala |

| 49 | Subhramanyam | 25 | Andhra Pradesh | |

| 50 | Ramaniklal Maganlal Modi | 38 | Gujarat | |

| 51 | Madanmohan Chaturvedi | 27 | Rajputana | Rajasthan |

| 52 | Harilal Mahimtura | 27 | Maharashtra | |

| 53 | Motibas Das | 20 | Odisha | |

| 54 | Haridas Muzumdar | 25 | Gujarat | |

| 55 | Anand Hingorini | 24 | Sindh | Sindh (Pakistan) |

| 56 | Mahadev Martand | 18 | Karnataka | |

| 57 | Jayantiprasad | 30 | United Provinces | |

| 58 | Hariprasad | 20 | United Provinces | |

| 59 | Girivardhari Chaudhari | 20 | Bihar | |

| 60 | Keshav Chitre | 25 | Maharashtra | |

| 61 | Ambalal Shankarbhai Patel | 30 | Gujarat | |

| 62 | Vishnu Pant | 25 | Maharashtra | |

| 63 | Premraj | 35 | Punjab | |

| 64 | Durgesh Chandra Das | 44 | Bengal | Bengal |

| 65 | Madhavlal Shah | 27 | Gujarat | |

| 66 | Jyotiram | 30 | United Provinces | |

| 67 | Surajbhan | 34 | Punjab | |

| 68 | Bhairav Dutt | 25 | United Provinces | |

| 69 | Lalji Parmar | 25 | Gujarat | |

| 70 | Ratnaji Boria | 18 | Gujarat | |

| 71 | Vishnu Sharma | 30 | Maharashtra | |

| 72 | Chintamani Shastri | 40 | Maharashtra | |

| 73 | Narayan Dutt | 24 | Rajputana | Rajasthan |

| 74 | Manilal Mohandas Gandhi | 38 | Gujarat | |

| 75 | Surendra | 30 | United Provinces | |

| 76 | Hari Krishna Mohoni | 42 | Maharashtra | |

| 77 | Puratan Buch | 25 | Gujarat | |

| 78 | Kharag Bahadur Singh Giri | 25 | Dehradun | Uttarakhand |

| 79 | Shri Jagat Narayan | 50 | Uttar Pradesh |

A memorial has been created inside the campus of IIT Bombay honouring these Satyagrahis who participated in the famous Dandi March.[59]

The Schedule of the March

| Date | Day | Mid Day Halt | Night Halt | km |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12-03-1930 | Wednesday | Chandola Talao | Aslali | 21 |

| 13-03-1930 | Thursday | Bareja | Navagam | 14 |

| 14-03-1930 | Friday | Vasna | Matar | 16 |

| 15-03-1930 | Saturday | Dabhan | Nadiad | 24 |

| 16-03-1930 | Sunday | Boriavi | Anand | 18 |

| 17-03-1930 | Monday | Rest Day at Anand | 0 | |

| 18-03-1930 | Tuesday | Napa | Borsad | 18 |

| 19-03-1930 | Wednesday | Ras | Kankarpura | 19 |

| 20-03-1930 | Thursday | Bank of Mahisagar | Kareli | 18 |

| 21-03-1930 | Friday | Gajera | Ankhi | 18 |

| 22-03-1930 | Saturday | Jambusar | Amod] | 19 |

| 23-03-1930 | Sunday | Buva | Samni | 19 |

| 24-03-1930 | Monday | Rest Day at Samni | 0 | |

| 25-03-1930 | Tuesday | Tralsa | Derol | 16 |

| 26-03-1930 | Wednesday | Bharuch | Ankleshwar | 21 |

| 27-03-1930 | Thursday | Sanjod | Mangarol | 19 |

| 28-03-1930 | Friday | Ryma | Umarachi | 16 |

| 29-03-1930 | Saturday | Erthan | Bhatgam | 16 |

| 30-03-1930 | Sunday | Sandhier | Delad | 19 |

| 31-03-1930 | Monday | Rest Day at Delad | 0 | |

| 01-04-1930 | Tuesday | Chaprabhata | Surat | 18 |

| 02-04-1930 | Wednesday | Dindoli | Vanz | 19 |

Mass civil disobedience

Mass civil disobedience spread throughout India as millions broke the salt laws by making salt or buying illegal salt.[20] Salt was sold illegally all over the coast of India. A pinch of salt made by Gandhi himself sold for 1,600 rupees (equivalent to $750 at the time). In reaction, the British government arrested over sixty thousand people by the end of the month.[54]

What had begun as a Salt Satyagraha quickly grew into a mass Satyagraha.[61] British cloth and goods were boycotted. Unpopular forest laws were defied in the Maharashtra, Karnataka and Central Provinces. Gujarati peasants refused to pay tax, under threat of losing their crops and land. In Midnapore, Bengalis took part by refusing to pay the chowkidar tax.[62] The British responded with more laws, including censorship of correspondence and declaring the Congress and its associate organisations illegal. None of those measures slowed the civil disobedience movement.[63]

There were outbreaks of violence in Calcutta (now spelled Kolkata), Karachi, and Gujarat. Unlike his suspension of satyagraha after violence broke out during the Non-co-operation movement, this time Gandhi was "unmoved". Appealing for violence to end, at the same time Gandhi honoured those killed in Chittagong and congratulated their parents "for the finished sacrifices of their sons ... A warrior's death is never a matter for sorrow."[64]

During the first phase of the civil disobedience movement from 1929 to 1931 there was a Labour government in power in Britain. The beatings at Dharasana, the shootings at Peshawar, the floggings and hangings at Solapur, the mass arrests, and much else were all presided over by a Labour prime minister, Ramsay MacDonald and his secretary of state, William Wedgwood Benn. The government was also complicit in a sustained attack on trade unionism in India,[65] an attack that Sumit Sarkar has described as "a massive capitalist and government counter-offensive" against workers' rights.[66]

Qissa Khwani Bazaar massacre

In Peshawar, satyagraha was led by a Muslim Pashtun disciple of Gandhi, Ghaffar Khan, who had trained 50,000 nonviolent activists called Khudai Khidmatgar.[67] On 23 April 1930, Ghaffar Khan was arrested. A crowd of Khudai Khidmatgar gathered in Peshawar's Qissa Kahani (Storytellers) Bazaar. The British ordered troops of 2/18 battalion of Royal Garhwal Rifles to open fire with machine guns on the unarmed crowd, killing an estimated 200–250.[68] The Pashtun satyagrahis acted in accord with their training in nonviolence, willingly facing bullets as the troops fired on them.[69] One British Indian Army Soldier Chandra Singh Garhwali and troops of the renowned Royal Garhwal Rifles, refused to fire at the crowds. The entire platoon was arrested and many received heavy penalties, including life imprisonment.[68]

Vedaranyam salt march

While Gandhi marched along India's west coast, his close associate C. Rajagopalachari, who would later become sovereign India's first Governor-General, organized the Vedaranyam salt march in parallel on the east coast. His group started from Tiruchirappalli, in Madras Presidency (now part of Tamil Nadu), to the coastal village of Vedaranyam. After making illegal salt there, he too was arrested by the British.[17]

Women in civil disobedience

The civil disobedience in 1930 marked the first time women became mass participants in the struggle for freedom. Thousands of women, from large cities to small villages, became active participants in satyagraha.[70] Gandhi had asked that only men take part in the salt march, but eventually women began manufacturing and selling salt throughout India. It was clear that though only men were allowed within the march, that both men and women were expected to forward work that would help dissolve the salt laws.[71] Usha Mehta, an early Gandhian activist, remarked that "Even our old aunts and great-aunts and grandmothers used to bring pitchers of salt water to their houses and manufacture illegal salt. And then they would shout at the top of their voices: 'We have broken the salt law!'"[72] The growing number of women in the fight for sovereignty and self-rule was a "new and serious feature" according to Lord Irwin. A government report on the involvement of women stated "thousands of them emerged ... from the seclusion of their homes ... in order to join Congress demonstrations and assist in picketing: and their presence on these occasions made the work the police was required to perform particularly unpleasant."[73] Though women did become involved in the march, it was clear that Gandhi saw women as still playing a secondary role within the movement, but created the beginning of a push for women to be more involved in the future.[71]

"Sarojini Naidu was among the most visible leaders (male or female) of pre-independent India. As president of the Indian National Congress and the first woman governor of free India, she was a fervent advocate for India, avidly mobilizing support for the Indian independence movement. She was also the first woman to be arrested in the salt march."[74]

Impact

British documents show that the British government was shaken by satyagraha. Nonviolent protest left the British confused about whether or not to jail Gandhi. John Court Curry, a British police officer stationed in India, wrote in his memoirs that he felt nausea every time he dealt with Congress demonstrations in 1930. Curry and others in British government, including Wedgwood Benn, Secretary of State for India, preferred fighting violent rather than nonviolent opponents.[73]

Dharasana Satyagraha and aftermath

Gandhi himself avoided further active involvement after the march, though he stayed in close contact with the developments throughout India. He created a temporary ashram near Dandi. From there, he urged women followers in Bombay (now spelled Mumbai) to picket liquor shops and foreign cloth. He said that "a bonfire should be made of foreign cloth. Schools and colleges should become empty."[64]

For his next major action, Gandhi decided on a raid of the Dharasana Salt Works in Gujarat, 40 km south of Dandi. He wrote to Lord Irwin, again telling him of his plans. Around midnight of 4 May, as Gandhi was sleeping on a cot in a mango grove, the District Magistrate of Surat drove up with two Indian officers and thirty heavily armed constables.[75] He was arrested under an 1827 regulation calling for the jailing of people engaged in unlawful activities, and held without trial near Poona (now Pune).[76]

The Dharasana Satyagraha went ahead as planned, with Abbas Tyabji, a seventy-six-year-old retired judge, leading the march with Gandhi's wife Kasturba at his side. Both were arrested before reaching Dharasana and sentenced to three months in prison. After their arrests, the march continued under the leadership of Sarojini Naidu, a woman poet and freedom fighter, who warned the satyagrahis, "You must not use any violence under any circumstances. You will be beaten, but you must not resist: you must not even raise a hand to ward off blows." Soldiers began clubbing the satyagrahis with steel tipped lathis in an incident that attracted international attention.[77] United Press correspondent Webb Miller reported that:

Not one of the marchers even raised an arm to fend off the blows. They went down like ten-pins. From where I stood I heard the sickening whacks of the clubs on unprotected skulls. The waiting crowd of watchers groaned and sucked in their breaths in sympathetic pain at every blow. Those struck down fell sprawling, unconscious or writhing in pain with fractured skulls or broken shoulders. In two or three minutes the ground was quilted with bodies. Great patches of blood widened on their white clothes. The survivors without breaking ranks silently and doggedly marched on until struck down ... Finally the police became enraged by the non-resistance ... They commenced savagely kicking the seated men in the abdomen and testicles. The injured men writhed and squealed in agony, which seemed to inflame the fury of the police ... The police then began dragging the sitting men by the arms or feet, sometimes for a hundred yards, and throwing them into ditches. [78]

Vithalbhai Patel, former Speaker of the Assembly, watched the beatings and remarked, "All hope of reconciling India with the British Empire is lost forever."[79] Miller's first attempts at telegraphing the story to his publisher in England were censored by the British telegraph operators in India. Only after threatening to expose British censorship was his story allowed to pass. The story appeared in 1,350 newspapers throughout the world and was read into the official record of the United States Senate by Senator John J. Blaine.[80]

Salt Satyagraha succeeded in drawing the attention of the world. Millions saw the newsreels showing the march. Time declared Gandhi its 1930 Man of the Year, comparing Gandhi's march to the sea "to defy Britain's salt tax as some New Englanders once defied a British tea tax".[81] Civil disobedience continued until early 1931, when Gandhi was finally released from prison to hold talks with Irwin. It was the first time the two held talks on equal terms,[82] and resulted in the Gandhi–Irwin Pact. The talks would lead to the Second Round Table Conference at the end of 1931.

Long-term effect

The Salt Satyagraha did not produce immediate progress toward dominion status or self-rule for India, did not elicit major policy concessions from the British,[83] or attract much Muslim support.[84] Congress leaders decided to end satyagraha as official policy in 1934, and Nehru and other Congress members drifted further apart from Gandhi, who withdrew from Congress to concentrate on his Constructive Programme, which included his efforts to end untouchability in the Harijan movement.[85] However, even though British authorities were again in control by the mid-1930s, Indian, British, and world opinion increasingly began to recognise the legitimacy of claims by Gandhi and the Congress Party for sovereignty and self-rule.[86] The Satyagraha campaign of the 1930s also forced the British to recognise that their control of India depended entirely on the consent of the Indians – Salt Satyagraha was a significant step in the British losing that consent.[87]

Nehru considered the Salt Satyagraha the high-water mark of his association with Gandhi,[88] and felt that its lasting importance was in changing the attitudes of Indians:

Of course these movements exercised tremendous pressure on the British Government and shook the government machinery. But the real importance, to my mind, lay in the effect they had on our own people, and especially the village masses ... Non-cooperation dragged them out of the mire and gave them self-respect and self-reliance ... They acted courageously and did not submit so easily to unjust oppression; their outlook widened and they began to think a little in terms of India as a whole ... It was a remarkable transformation and the Congress, under Gandhi's leadership, must have the credit for it.[89]

More than thirty years later, Satyagraha and the March to Dandi exercised a strong influence on American civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr., and his fight for civil rights for blacks in the 1960s:

Like most people, I had heard of Gandhi, but I had never studied him seriously. As I read I became deeply fascinated by his campaigns of nonviolent resistance. I was particularly moved by his Salt March to the Sea and his numerous fasts. The whole concept of Satyagraha (Satya is truth which equals love, and agraha is force; Satyagraha, therefore, means truth force or love force) was profoundly significant to me. As I delved deeper into the philosophy of Gandhi, my skepticism concerning the power of love gradually diminished, and I came to see for the first time its potency in the area of social reform.[9]

Re-enactment in 2005

To commemorate the Great Salt March, the Mahatma Gandhi Foundation re-enacted the Salt March on its 75th anniversary, in its exact historical schedule and route followed by the Mahatma and his band of 78 marchers. The event was known as the "International Walk for Justice and Freedom". What started as a personal pilgrimage for Mahatma Gandhi's great-grandson Tushar Gandhi turned into an international event with 900 registered participants from nine nations and on a daily basis the numbers swelled to a couple of thousands. There was extensive reportage in the international media.

The participants halted at Dandi on the night of 5 April, with the commemoration ending on 7 April. At the finale in Dandi, the prime minister of India, Dr Manmohan Singh, greeted the marchers and promised to build an appropriate monument at Dandi to commemorate the marchers and the historical event. The route from Sabarmati Ashram to Dandi has now been christened as the Dandi Path and has been declared a historical heritage route.[90][91]

Series of commemorative stamps were issued in 1980 and 2005, on the 50th and 75th anniversaries of the Dandi March.[92]

Memorial

The National Salt Satyagraha Memorial, a memorial museum, dedicated to the event was opened in Dandi on 30 January 2019.

See also

References

Citations

- "National Salt Satyagraha Memorial | List of names" (PDF). Dandi Memorial. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- "Salt March". Oxford Encyclopedia of the Modern World. Oxford University Press. 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- "Mass civil disobedience throughout India followed as millions broke the salt laws", from Dalton's introduction to Gandhi's Civil Disobedience, Gandhi and Dalton, p. 72.

- Dalton, p. 92.

- Johnson, p. 234.

- Ackerman, p. 106.

- "Its root meaning is holding onto truth, hence truth-force. I have also called it Love-force or Soul-force." Gandhi (2001), p. 6.

- Martin, p. 35.

- King Jr., Martin Luther; Carson, Clayborne (1998). The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. Warner Books. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-446-67650-2.

- Eyewitness Gandhi (1 ed.). London: Dorling Kinderseley Ltd. 2014. p. 44. ISBN 978-0241185667. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- Wolpert, Stanley A. (2001). Gandhi's passion : the life and legacy of Mahatma Gandhi. Oxford University Press. pp. 141. ISBN 019513060X. OCLC 252581969.

- Wolpert, Stanley (1999). India. University of California Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-520-22172-7.

- Ackerman, p. 83.

- Dalton, p. 91.

- Dalton, p. 100.

- "Nehru, who had been skeptical about salt as the primary focus of the campaign, realized how wrong he was ..." Johnson, p. 32.

- Gandhi, Gopalkrishna. "The Great Dandi March — eighty years after", The Hindu, 5 April 1930

- Letter to London on 20 February 1930. Ackerman, p. 84.

- Gross, David M. (2014). 99 Tactics of Successful Tax Resistance Campaigns. Picket Line Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-1490572741.

- Gandhi and Dalton, p. 72.

- "Gandhi's ideas about satyagraha and swaraj, moreover, galvanised the thinking of Congress cadres, most of whom by 1930 were committed to pursuing sovereignty and self-rule by nonviolent means." Ackerman, p. 108.

- Dalton, pp. 9–10.

- Hind Swaraj, Gandhi and Dalton, p. 15.

- Forward to volume of Gokhale's speeches, "Gopal Krishna Gokahalenan Vyakhyanao" from Johnson, p. 118.

- Satyagraha in South Africa, 1926 from Johnson, p. 73.

- Dalton, p. 48.

- Dalton, p. 93.

- Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi 41: 208–209

- Dalton, p. 94.

- Dalton, p. 95.

- "Chronology: Event Detail Page". Gandhi Heritage Portal. 15 June 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- Dalton, p. 113.

- Dalton, p. 108.

- Dalton, p. 107.

- Dalton, p. 104.

- Dalton, p. 105.

- Ackerman, p. 85.

- "The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi". Gandhi Heritage Portal. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- Gandhi's letter to Irwin, Gandhi and Dalton, p. 78.

- Majmudar, Uma; Gandhi, Rajmohan (2005). Gandhi's Pilgrimage of Faith: From Darkness To Light. New York: SUNY Press. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-7914-6405-2.

- "Parliament Museum, New Delhi, India – Official website – Dandi March VR Video". Parliamentmuseum.org. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- Miller, Herbert A. (23 April 1930) "Gandhi's Campaign Begins", The Nation.

- Dalton, p. 107

- "Dandi march: date, history facts. All you need to know". Website of Indian National Congress. 25 October 2018. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- Weber, p. 140.

- The Statesman, 13 March 1930.

- "The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi". Gandhi Heritage Portal. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- Weber, pp. 143–144.

- Ackerman, p. 86.

- "The March to Dandi". English.emory.edu. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- "The Man – The Mahatma : Dandi March". Library.thinkquest.org. Archived from the original on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- Dalton, p. 221.

- Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi 43: 180, Wolpert, p. 148

- Jack, pp. 238–239.

- "The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi". Gandhi Heritage Portal. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- Jack, p. 240.

- "Mapping the unknown marcher". The Indian Express. 9 February 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- "Chronology: Event Detail Page". Gandhi Heritage Portal. 15 June 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- "Photos: Remembering the 80 unsung heroes of Mahatma Gandhi's Dandi March". The Indian Express. 9 February 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- Ministry of Culture, GOI. "Brouchure issued by Ministry of Culture, GOI on NSSM" (PDF). NSSMprojectbrochure. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- "The Salt Satyagraha in the meantime grew almost spontaneously into a mass satyagraha." Habib, p. 57.

- Habib, p. 57.

- "Correspondence came under censorship, the Congress and its associate organizations were declared illegal, and their funds made subject to seizure. These measures did not appear to have any effect on the movement..." Habib, p. 57.

- Wolpert, p. 149.

- Newsinger, John (2006). The Blood Never Dried: A People's History of the British Empire. Bookmarks Publications. p. 144.

- Sarkar, S (1983). Modern India 1885–1947. Basingstoke. p. 271.

- Habib, p. 55.

- Habib, p. 56.

- Johansen, Robert C. (1997). "Radical Islam and Nonviolence: A Case Study of Religious Empowerment and Constraint Among Pashtuns". Journal of Peace Research. 34 (1): 53–71 [62]. doi:10.1177/0022343397034001005. S2CID 145684635.

- Chatterjee, Manini (July–August 2001). "1930: Turning Point in the Participation of Women in the Freedom Struggle". Social Scientist. 29 (7/8): 39–47 [41]. doi:10.2307/3518124. JSTOR 3518124.

...first, it is from this year (1930) that women became mass participants in the struggle for freedom.... But from 1930, that is in the second non-cooperation movement better known as the Civil Disobedience Movement, thousands upon thousands of women in all parts of India, not just in big cities but also in small towns and villages, became part of the satyagraha struggle.

- Kishwar, Madhu (1986). "Gandhi on Women". Race & Class. 28 (41): 1753–1758. doi:10.1177/030639688602800103. JSTOR 4374920. S2CID 143460716.

- Hardiman, David (2003). Gandhi in His Time and Ours: The Global Legacy of His Ideas. Columbia University Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-231-13114-8.

- Johnson, p. 33.

- Arsenault, Natalie (2009). Restoring Women to World Studies (PDF). The University of Texas at Austin. pp. 60–66.

- Jack, pp. 244–245.

- Riddick, John F. (2006). The History of British India: A Chronology. Greenwood Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-313-32280-8.

- Ackerman, pp. 87–90.

- Webb Miller's report from May 21, Martin, p. 38.

- Wolpert, p. 155.

- Singhal, Arvind (2014). "Mahatma is the Message: Gandhi's Life as Consummate Communicator". International Journal of Communication and Social Research. 2 (1): 4.

- "Man of the Year, 1930". Time. 5 January 1931. Retrieved 17 November 2007.

- Gandhi and Dalton, p. 73.

- Ackerman, p. 106: "...made scant progress toward either dominion status within the empire or outright sovereignty and self-rule. Neither had they won any major concessions on the economic and mundane issues that Gandhi considered vital."

- Dalton, p. 119-120.

- Johnson, p. 36.

- "Indian, British, and world opinion increasingly recognized the legitimate claims of Gandhi and Congress for Indian independence." Johnson, p. 37.

- Ackerman, p. 109: "The old order, in which British control rested comfortably on Indian acquiescence, had been sundered. In the midst of civil disobedience, Sir Charles Innes, a provincial governor, circulated his analysis of events to his colleagues. "England can hold India only by consent," he conceded. "We can't rule it by the sword." The British lost that consent...."

- Fisher, Margaret W. (June 1967). "India's Jawaharlal Nehru". Asian Survey. 7 (6): 363–373 [368]. doi:10.1525/as.1967.7.6.01p02764.

- Johnson, p. 37.

- "Gandhi's 1930 march re-enacted". BBC News. 12 March 2005. Retrieved 27 December 2007.

- Diwanji, Amberish K (15 March 2005). "In the Mahatma's footsteps". Rediff. Retrieved 27 December 2007.

- Category:Salt March on stamps. commons.wikimedia.org

Cited sources

- Ackerman, Peter; DuVall, Jack (2000). A Force More Powerful: A Century of Nonviolent Conflict. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-24050-9.

- Dalton, Dennis (1993). Mahatma Gandhi: Nonviolent Power in Action. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231122375.

- Gandhi, Mahatma; Dalton, Dennis (1996). Selected Political Writings. Hackett Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-87220-330-3.

- Habib, Irfan (September–October 1997). "Civil Disobedience 1930–31". Social Scientist. 25 (9–10): 43–66. doi:10.2307/3517680. JSTOR 3517680.

- Jack, Homer A., ed. (1994). The Gandhi Reader: A Source Book of His Life and Writings. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-3161-4.

- Johnson, Richard L. (2005). Gandhi's Experiments With Truth: Essential Writings By And About Mahatma Gandhi. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-1143-7.

- Martin, Brian (2006). Justice Ignited. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-4086-6.

- Weber, Thomas (1998). On the Salt March: The Historiography of Gandhi's March to Dandi. India: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-81-7223-372-3.

- Wolpert, Stanley (2001). Gandhi's Passion: The Life and Legacy of Mahatma Gandhi. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515634-8.

Further reading

- Decourcy, Elisa. "Just a grain of salt?: Symbolic construction during the Indian nationalist movement," Melbourne Historical Journal, 1930, Vol. 38, pp 57–72

- Gandhi, M. K. (2001). Non-Violent Resistance (Satyagraha). Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-41606-9.

- Masselos, Jim. "Audiences, Actors and Congress Dramas: Crowd Events in Bombay City in 1930," South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, April 1985, Vol. 8 Issue 1/2, pp 71–86

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Salt March. |

- Newsreel footage of Salt Satyagraha

- Salt march re-enactment slide show

- Gandhi's 1930 march re-enacted (BBC News)

- Speech by Prime Minister of India on 75th anniversary of Dandi March.

- Dandi March Timeline