Fourth Anglo-Mysore War

The Fourth Anglo–Mysore War was a conflict in South India between the Kingdom of Mysore against the British East India Company and the Hyderabad Deccan in 1798–99.[4]

| Fourth Anglo–Mysore War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Anglo-Mysore wars | |||||||

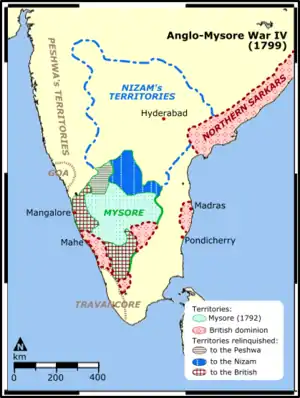

A map of the war thereafter | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Supported by: The Carnatic (suspected) |

East India Company | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Tipu Sultan † Sipahsalar Sayyid Abdul Ghaffar Sahib Mir Golam Hussain Mohomed Hulleen Mir Miran Mir Sadiq Ghulam Muhammad Khan |

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| c. 37,000[3] |

East India Company: Tens of thousands Hyderabad: 4 infantry battalions[2] 10,000 cavalry[1] | ||||||

This was the final conflict of the four Anglo-Mysore Wars. The British captured the capital of Mysore. The ruler Tipu Sultan was killed in the battle. Britain took indirect control of Mysore, restoring the Wodeyar Dynasty to the Mysore throne (with a British commissioner to advise him on all issues). Tipu Sultan's young heir, Fateh Ali, was sent into exile. The Kingdom of Mysore became a princely state in a subsidiary alliance with British India covering parts of present Kerala-Karnataka and ceded Coimbatore, Dakshina Kannada and Uttara Kannada to the British.

Background

Napoleon Bonaparte's landing in Ottoman Egypt in 1798 was intended to further the capture of the British possessions in India, and the Kingdom of Mysore was a key to that next step, as the ruler of Mysore, Tipu Sultan, sought France as an ally and his letter to Napoleon resulted in the following reply, "You have already been informed of my arrival on the borders of the Red Sea, with an innumerable and invincible army, full of the desire of releasing and relieving you from the iron yoke of England." Additionally, General Malarctic, French Governor of Mauritius, issued the Malarctic Proclamation seeking volunteers to assist Tipu. Horatio Nelson ended any possibility of help from Napoleon after the Battle of the Nile. However, Lord Wellesley had already set in motion a response to prevent any alliance between Tipu Sultan and France.[5]

Course of Events

Three armies – one from Bombay and two British (one of which contained a division that was commanded by Colonel Arthur Wellesley, the future 1st Duke of Wellington), marched into Mysore in 1799 and besieged the capital, Srirangapatnam, after some engagements with Tipu. On 8 March, a forward force managed to hold off an advance by Tipu at the Battle of Seedaseer. On 4 May, in the Battle of Seringapatam, broke through the defending walls. Tipu Sultan, rushing to the breach, was shot and killed.

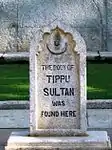

Today, the spot where Tipu's body was discovered under the eastern gate has been fenced off by the Archaeological Survey of India, and a plaque erected. The gate was later demolished during the 19th century to lay a wide road.

One notable military advance championed by Tipu Sultan was the use of mass attacks with iron-cased rocket brigades in the army. The effect of the Mysorean rockets on the British during the Third and Fourth Mysore Wars was sufficiently impressive to inspire William Congreve to develop the Congreve rockets.

Many members of the East India Company believed that Umdat Ul-Umra, the Nawab of Carnatic, secretly provided assistance to Tipu Sultan during the Fourth Anglo–Mysore War; and they immediately sought his deposition after the end of the conflict.

Nawab of Savanur

Territory of the Nawab of Savanur were split among the English and Maratha forces.

Mysorean rockets

During the war, rockets were again used on several occasions. One of these involved Colonel Arthur Wellesley, later famous as the First Duke of Wellington. Wellesley was defeated by Tipu's Diwan, Purnaiah, at the Battle of Sultanpet Tope. Quoting Forrest,

At this point (near the village of Sultanpet, Figure 5) there was a large tope, or grove, which gave shelter to Tipu's rocketmen and had obviously to be cleaned out before the siege could be pressed closer to Srirangapattana island. The commander chosen for this operation was Col. Wellesley, but advancing towards the tope after dark on the 5 April 1799, he was set upon with rockets and musket-fires, lost his way and, as Beatson politely puts it, had to "postpone the attack" until a more favourable opportunity should offer.[6]

The following day, Wellesley launched a fresh attack with a larger force, and took the whole position without losing a single man.[7] On 22 April 1799, twelve days before the main battle, rocketeers worked their way around to the rear of the British encampment, then 'threw a great number of rockets at the same instant' to signal the beginning of an assault by 6,000 Indian infantry and a corps of Frenchmen, all directed by Mir Golam Hussain and Mohomed Hulleen Mir Miran. The rockets had a range of about 1,000 yards. Some burst in the air like shells. Others, called ground rockets, would rise again on striking the ground and bound along in a serpentine motion until their force was spent. According to one British observer, a young English officer named Bayly: "So pestered were we with the rocket boys that there was no moving without danger from the destructive missiles ...". He continued:

The rockets and musketry from 20,000 of the enemy were incessant. No hail could be thicker. Every illumination of blue lights was accompanied by a shower of rockets, some of which entered the head of the column, passing through to the rear, causing death, wounds, and dreadful lacerations from the long bamboos of twenty or thirty feet, which are invariably attached to them.

During the conclusive British attack on Srirangapattana on 2 May 1799, a British shot struck a magazine of rockets within Tipu Sultan's fort, causing it to explode and send a towering cloud of black smoke with cascades of exploding white light rising up from the battlements. On the afternoon of 4 May when the final attack on the fort was led by Baird, he was again met by "furious musket and rocket fire", but this did not help much; in about an hour's time the fort was taken; perhaps within another hour Tipu had been shot (the precise time of his death is not known), and the war was effectively over.[8]

In popular culture

The war, specifically the Battle of Mallavelly and the Siege of Seringapatam, with many of the key protagonists, is covered in the historical novel Sharpe's Tiger by Bernard Cornwell.[9]

Gallery

- Fall of Tippu Sultan (1799)

Tipu Sultan's forces during the Siege of Srirangapatna.

Tipu Sultan's forces during the Siege of Srirangapatna. The Last Effort of Tippu Sahib at Seringapatam (Corner, 1840, p. 334)[10]

The Last Effort of Tippu Sahib at Seringapatam (Corner, 1840, p. 334)[10] The Last Effort and Fall of Tipu Sultan by Henry Singleton, c. 1800

The Last Effort and Fall of Tipu Sultan by Henry Singleton, c. 1800 British troops examine the body of Tipu Sultan

British troops examine the body of Tipu Sultan David Baird, a British officer, discovering the body of Tipu Sultan.

David Baird, a British officer, discovering the body of Tipu Sultan. British Marker showing the location where Tipu's body was found.

British Marker showing the location where Tipu's body was found.

| Preceded by Third Anglo-Mysore War |

Anglo-Mysore Wars | Succeeded by None |

| Preceded by Third Anglo–Mysore War |

Indo-British conflicts | Succeeded by Second Anglo-Maratha War |

References

- Dalrymple (2003), p. 180.

- Dalrymple (2003), p. 179.

- Dalrymple (2003), p. 191.

- George Childs Kohn (31 October 2013). Dictionary of Wars. Routledge. pp. 322–323. ISBN 978-1-135-95494-9.

- Naravane, M.S. (2018). Battles of the Honorourable East India Company. A.P.H. Publishing Corporation. pp. 178–181. ISBN 9788131300343.

- Forrest D (1970) Tiger of Mysore, Chatto & Windus, London

- Holmes, Richard (2003). Wellington: The Iron Duke. Harper Collins. p. 58. ISBN 0-00-713750-8.

- Narasimha, Roddam. "Rockets in Mysore and Britain, 1750-1850 A.D." (PDF). National Aerospace Laboratories. nal.res.in.

- "Website of Bernard Cornwell". 26 May 2019. Archived from the original on 2 February 2007.

- Corner, Julia (1840). The History of China & India, Pictorial & Descriptive (PDF). London: Dean & Co., Threadneedle St. p. 334. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

Works cited

- Dalrymple, William (2003) [1st pub. 2002]. White Mughals: love and betrayal in eighteenth-century India. Flamingo (HarperCollins). ISBN 9780006550969.

Further reading

- Bonghi, Ruggero (1869), "Chapter-XIX: Lord Wellesley's administration—Fourth and last Mysore war, 1798, 1799", in Marshman, John Clark (ed.), The History of India from the Earliest Period to the Close of Lord Dalhousie's, 2, Longmans, Green, Reader & Dyer, pp. 71–102

- Carter, Thomas (1861), "The Mysore War and the Siege of Seringapatam", India, China, etc, Medals of the British Army: And how They Were Won, 3, Groombridge and sons, pp. 2–6

- Mill, James; Wilson, Horace Hayman (1858), "Chapter-VIII", The History of British occupied India, 6 (5 ed.), J. Madden, pp. 50–121