Chang'e 5

Chang'e 5 (Chinese: 嫦娥五号; pinyin: Cháng'é wǔhào[note 1]) is the fifth lunar exploration mission of the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program, and China's first lunar sample-return mission.[9] Like its predecessors, the spacecraft is named after the Chinese moon goddess Chang'e. It launched at 20:30 UTC on 23 November 2020 from Wenchang Spacecraft Launch Site on Hainan Island, landed on the Moon on 1 December 2020, collected ~1,731 g (61.1 oz) of lunar samples (including from a core ~1 m deep),[10][11] and returned to the Earth at 17:59 UTC on 16 December 2020.

Chang'e 5 probe separating from the launcher (artist's impression) | |

| Mission type | Lunar sample return |

|---|---|

| Operator | CNSA |

| COSPAR ID | 2020-087A |

| SATCAT no. | 47097 |

| Mission duration | Primary mission: 22 days, 21 hours, 29 minutes Extended mission: 73 days, 21 hours, 51 minutes |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | CAST |

| Launch mass | 8,200 kg (18,100 lb) |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 23 November 2020 20:30 UTC 24 November 2020 04:30 CST[1] |

| Rocket | Long March 5 |

| Launch site | Wenchang |

| Contractor | CALT |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | 16 December 2020, 17:59 UTC Return capsule |

| Landing site | Inner Mongolia, China |

| Lunar orbiter | |

| Orbital insertion | 28 November 2020 12:58 UTC[2] |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Periapsis altitude | 400 km (250 mi)[2] |

| Lunar lander | |

| Landing date | 1 December 2020[3] |

| Return launch | 3 December 2020 |

| Landing site | Mons Rümker, region of Oceanus Procellarum[4][5] |

| Sample mass | 1,731 g (61.1 oz)[6] |

| Chang'e 5 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 嫦娥五号 | ||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 嫦娥五號 | ||||||

| |||||||

Chang'e-5 mission is the first lunar sample-return mission conducted by humanity in over four decades since the Soviet Union's Luna 24 in 1976. By completing the mission, China became the third country to return samples from the Moon after the United States and the Soviet Union.

Overview

The Chinese Lunar Exploration Program has four phases, with incremental technological advancement:[12][13]

- Phase two: soft landing and deploying rover on the Moon, completed by Chang'e 3 (2013) [15] and Chang'e 4 (launched in December 2018, landed on the far side of the Moon in January 2019).[16]

- Phase three: returning lunar samples, completed by Chang'e 5. The backup of Chang'e-5, the Chang'e 6 mission, is also a lunar sample-return mission.

- Phase four: in-situ resource utilization, and constructing an International Lunar Research Station near the lunar south pole.[12]

The Chinese Lunar Exploration Program will finally lead to the crewed missions in the 2030s.[12][13]

Equipments

Components

The Chang'e-5 mission consists of four modules or components:

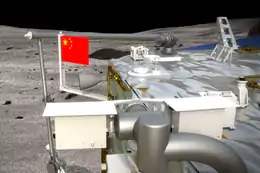

- Lander: landed on the lunar surface after separating from the Orbiter, installed with a drill and a scooping device. The Ascender is on the top of the Lander.

- Ascender: after sampling, the lunar samples have been transported to container within the Ascender. The Ascender launched from the lunar surface at 23:11 UTC, on 3 December 2020, followed by automatic lunar orbit rendezvous and docking with the Orbiter. After transfering the sample, the Ascender separated from the Orbiter, deorbited and fell back down on the Moon at 22:49 UTC, on 8 December 2020, to avoid becoming space debris.

- Orbiter: after the samples transported from the Ascender to the Orbiter, the Orbiter left the lunar orbit and spent ~4.5 days flying back to the Earth orbit and released the Returner (reentry capsule) just before arrival.

- Returner: The Returner performed a skip reentry to bounce off the atmosphere once before formal reentering.

The four components were launched together and fly to the Moon as a combined unit. After reaching the lunar orbit (14:58 UTC, on 28 November 2020), the Lander/Ascender separated from the Orbiter/Returner modules (20:40 UTC, on 29 November 2020), and descended to the surface of the Moon (15:13 UTC, on 1 December 2020). After samples have been collected, the Ascender separated from the Lander (15:11 UTC, on 3 December 2020), lifted off to the Orbiter/Returner, docked with them, and transferred the samples to the Returner. The Ascender then separated from the Orbiter/Returner and smashed at the Moon (~30°S in latitude and 0° in longitude) at 22:49 UTC, on 8 December 2020. The Orbiter/Returner then returned to the Earth, where the Returner separated and descended to the surface of the Earth at 17:59 UTC, on 16 December 2020.

The estimated launch mass of Chang'e-5 is 8,200 kg (18,100 lb),[17] the Lander is projected to be 1,200 kg (2,600 lb) and Ascender is about 500 kg (1,100 lb). Unlike Chang'e 4, which was equipped with a radioisotope heater unit to survive the extreme cold of lunar night, the Lander of Chang'e-5 ended in the following lunar night.

Scientific Payloads

Chang'e-5 includes four scientific payloads, including a Landing Camera, a Panoramic Camera, a Lunar Mineralogical Spectrometer,[18] and a Lunar Regolith Penetrating Radar.[19][20] Chang'e-5 collected samples using two methods, i.e., drilling for subsurface samples and scooping for surface samples. The scooping device was developed by The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, consisting of Sampler A, Sampler B, Near-field Cameras, and Sealing and Packaging System.[21]

Mission profile

Launch

Chang'e 5 was planned to be launched in November 2017 by the Long March 5 rocket; however, a July 2017 failure of the referenced carrier rocket forced a delay to the original schedule two times until the end of 2020.[22] On 27 December 2019, the Long March 5 successfully returned to services, thereby allowing the current mission to proceed after Tianwen-1 mission.[23] The Chang'e 5 probe was launched at 20:30 UTC, on 23 November 2020, by Long March 5 Y-5 launch vehicle from the Wenchang Spacecraft Launch Site on Hainan Island.

Earth-Moon Transfer

After launch, Chang'e-5 applied its first orbital correction at 14:06 UTC, on 24 November 2020, second orbital correction at 14:06 UTC, on 25 November 2020, entered the lunar orbital at 14:58 UTC, on 28 November 2020 (elliptical orbital), adjusted its orbit to a circular orbit at 12:23 UTC, on 29 November 2020, and the Lander/Ascender separated from the Orbiter/Returner at 20:10 UTC, on 29 November 2020, in preparing for landing.[24]

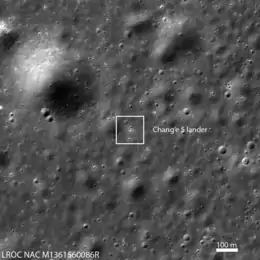

Landing site

The Lander/Ascender landed on the Moon on 1 December 2020 at 15:11 UTC.[25] The Chang'e 5 landing site is at 43.1°N (in latitude), 51.8°W (in longitude) in the Northern Oceanus Procellarum near a huge volcanic complex, Mons Rümker,[26] located in the northwest lunar near side. The Chang'e 5 landing site is within the Procellarum KREEP Terrain,[27] with elevated heat-producing elements, thin crust, and prolonged volcanism. This area is characterized by some of the youngest mare basalts on the Moon (~1.21 billion years old),[28] with elevated titanium, thorium, and olivine abundances,[28] which have never been sampled by Apollo or Luna mission. It is hoped that the young age of the returned samples collected will allow scientists to improve our understanding of the lunar impact and late thermal evolution history.[2]

Back to the Earth

The Chang'e 5 Ascender lifted off from Oceanus Procellarum at 15:10 UTC, on 3 December 2020, and six minutes later, arrived in lunar orbit.[29] The Ascender docked with the Orbiter/Returner combination in the lunar orbit on 5 December 2020 at 21:42 UTC, and the samples were transferred to the return capsule at 22:12 UTC. The Ascender separated from the Orbiter/Returner combination on 6 December 2020 at 04:35 UTC.[30] After completing its role of the mission, the Ascender was commanded to deorbit on 7 December 2020, at 22:59 UTC, and crashed into the Moon's surface at 23:30 UTC, in the area of (~30°S, 0°E).[31] On 13 December 2020 at 01:51 UTC, from a distance of 230 kilometers from the lunar surface, the Orbiter and Returner successfully fired four engines to enter the Moon-Earth Hohmann transfer orbit.[32]

The electronics and systems on the Chang'e 5 lunar lander were expected to cease working on 11 December 2020, due to the Moon's extreme cold and lack of a radioisotope heater unit. However, engineers were also prepared for the possibility that the Chang'e 5 lander could be damaged and stop working after acting as the launchpad for the ascender module on 3 December 2020, as turned out to be the case.[33]

On 16 December 2020 at around 18:00 UTC, the roughly 300 kg (660 lb) return capsule performed a ballistic skip reentry, in effect bouncing off the atmosphere over the Arabian Sea before re-entry. The capsule, containing around 2 kg (4.4 lb) of drilled and scooped lunar material, landed in the grasslands of Siziwang Banner in the Ulanqab region of south central Inner Mongolia. Surveillance drones spotted the Returner capsule prior to its touchdown, and recovery vehicles located the capsule shortly afterwards.[34]

The next day, it was reported that Chang'e 5's service module had performed an atmospheric re-entry avoidance burn and has been on-course to an Earth-Sun L1 Lagrange point orbit as a part of its extended mission.

Lunar sample research

The ~1,731 g (61.1 oz) of lunar samples collected by Chang'e-5 have enormous scientific meanings in terms of their abnormally young ages (<2.0 billion years old).[28][2] At least, 27 fundamental questions can be answered by those samples on lunar chronology, petrogenesis, regional setting, geodynamic and thermal evolution, and regolith formation, especially, calibrating the lunar chronology function, constraining the lunar dynamo status, unraveling the deep mantle properties, and assessing the Procellarum KREEP Terrain structures.[2]

Verifying the ages of those samples would provide data on the hypothesis that some areas of the Moon experienced late-stage volcanism, and compositional analysis could provide insights into the reasons behind it. Katherine Joy of the University of Manchester considers that the samples might represent some of the last lunar lava flows to have erupted. "If so, they not only tell us about the Moon's thermal history but these are also vital samples to help us calibrate the Moon's impact history".[35] Dating this relatively young part of the Moon's surface would provide an additional calibration point for estimating the surface ages of other Solar System bodies.[35][36] Wu Yanhua (吴艳华), deputy director of the China National Space Administration (CNSA) announced that the new samples will be shared with the UN and international partners for space research purposes.[37][38]

Related missions

Chang'e 5-T1

Chang'e 5-T1 is an experimental robotic lunar mission that was launched on 23 October 2014 to conduct atmospheric re-entry tests on the capsule design that was planned to be used in the Chang'e 5 mission.[39][40] Its service module, called DFH-3A, remained in orbit around the Earth before being relocated via Earth–Moon L2 to lunar orbit by 13 January 2015, where it is using its remaining 800 kg of fuel to test maneuvers critical to future lunar missions.[41]

International collaboration

The European Space Agency (ESA) has supported the Chang'e 5 mission by providing tracking via ESA's Kourou station located in French Guiana. ESA has tracked the spacecraft during the launch and landing phases while providing on-call backup for China's ground stations throughout the mission. Data from the Kourou station has helped the mission control team at the Beijing Aerospace Flight Control Center to determine the spacecraft's health and orbit status. Chang'e 5 was returned to Earth on 16 December 2020. During the landing phase, ESA used its Maspalomas Station located in the Canary Islands and operated by the Instituto Nacional de Técnica Aeroespacial (INTA) in Spain, to support the tracking efforts.[42]

International reactions

Science journalist Bob McDonald discussed Chang'e 5 in comparison to the Soviet Luna programme, which involved Luna 15, Luna 16 and Luna 24 being sent to the Moon. Luna 15 attempted to grab a sample of lunar soil and return it to Earth before the American Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin got back in July 1969. It crashed during its landing attempt, hence losing the opportunity for a "propaganda coup". The Luna 16 mission successfully returned about 100 grams of lunar soil a year later and two other sample return missions succeeded in subsequent years, the most recent being Luna 24 in 1976. McDonald considers that China has entered another Moon race.[43]

Bradley Perrett, Asia-Pacific Bureau Chief of Aviation Week Network, opined that the Moon race between the Soviet Union and the United States in the 1960s was driven by propaganda: a message to the world about their strength. Perrett noted that the Chang'e project was also driven by propaganda utility, but primarily for the internal audience; the reason that the Chinese government funded this mission was to show the Chinese people that it can be done.[44]

Simon Sharwood, APAC Editor of The Register, observed that the mission was a success that went off without a hitch, even with the damage to the lander when the ascender lifted off. Sharwood said that Chinese youth already has a lot to aspire given that China plans to build a space station and moon base in the future. Sharwood went on to say that such opportunities, however, will not be possible to all of them, based on his understanding of the relationship between technology and government in China.[45][46]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chang'e 5. |

Footnotes

- In Standard Chinese, it is pronounced as Cháng'é.[7] Alternatively pronounced and spelled like Chang-Er in Malaysian Chinese.[8]

References

- "NASA - NSSDCA Spacecraft Details - Chang'e 5". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Qian, Yuqi; Xiao, Long; Head, James W.; van der Bogert, Carolyn H.; Hiesinger, Harald; Wilson, Lionel (February 2021). "Young lunar mare basalts in the Chang'e-5 sample return region, northern Oceanus Procellarum". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 555: 116702. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2020.116702.

- Berger, Eric. "China Chang'e 5 probe has safely landed on the Moon". arstechnica.com. Archived from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- Williams, David R. (7 December 2018). "Future Chinese Lunar Missions". NASA. Archived from the original on 4 January 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Jones, Andrew (7 June 2017). "China confirms landing site for Chang'e-5 Moon sample return". GB Times. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- "China's Chang'e-5 retrieves 1,731 grams of moon samples". Xinhua News Agency. 19 December 2020. Archived from the original on 20 December 2020. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- Lemei, Yang (2006). "China's Mid-Autumn Day". Journal of Folklore Research. Indiana University Press. 43 (3): 263–270. doi:10.2979/JFR.2006.43.3.263. S2CID 161494297. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

China's Mid-Autumn Day, a traditional occasion to celebrate family unity and harmony, is related to two Chinese tales. The first is the myth of Cháng'é, who flew to the moon, where she has dwelt ever since.

- Loong, Gary Lit Ying (27 September 2020). "Of mooncakes and moon-landing". New Straits Times. Malaysia. Archived from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- Liu, Jianjun; Zeng, Xingguo; Li, Chunlai; Ren, Xin; Yan, Wei; Tan, Xu; Zhang, Xiaoxia; Chen, Wangli; Zuo, Wei; Liu, Yuxuan; Liu, Bin (February 2021). "Landing Site Selection and Overview of China's Lunar Landing Missions". Space Science Reviews. 217 (1): 6. doi:10.1007/s11214-020-00781-9. ISSN 0038-6308.

- CNSA. "China's Chang'e-5 retrieves 1,731 kilograms of moon samples".

- Jones, Andrew. "China says it's open to sharing moon rocks as Chang'e 5 samples head to the lab". space.com. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- Xu, Lin. "China's Lunar and Deep Space Exploration Program for the Next Decade (2020-2030)". Chinese Journal of Space Science. 40: 615–617.

- Yang, Ruihong; Zhang, Yuhua; Kang, Yan; Wang, Qian; Ma, Jinan; Zou, Yongliao; He, Huaiyu; Wang, Wei; Zhang, He; Pei, Zhaoyu; Wang, Qiong (1 August 2020). "Overview of lunar exploration and International Lunar Research Station". Chinese Science Bulletin. 65 (24): 2577–2586. doi:10.1360/TB-2020-0582. ISSN 0023-074X.

- Ziyuan, Ouyang; Chunlai, Li; Yongliao, Zou; Hongbo, Zhang; Chang, Lu; Jianzhong, Liu; Jianjun, Liu; Wei, Zuo; Yan, Su; Weibin, Wen; Wei, Bian (15 September 2010). "Chang'E-1 lunar mission: an overview and primary science results". 空间科学学报 (in English and Chinese). 30 (5): 392–403. doi:10.11728/cjss2010.05.392. ISSN 0254-6124.

- Li, Chunlai; Liu, Jianjun; Ren, Xin; Zuo, Wei; Tan, Xu; Wen, Weibin; Li, Han; Mu, Lingli; Su, Yan; Zhang, Hongbo; Yan, Jun (July 2015). "The Chang'e 3 Mission Overview". Space Science Reviews. 190 (1–4): 85–101. doi:10.1007/s11214-014-0134-7. ISSN 0038-6308.

- Jia, Yingzhuo; Zou, Yongliao; Ping, Jinsong; Xue, Changbin; Yan, Jun; Ning, Yuanming (November 2018). "The scientific objectives and payloads of Chang'e 4 mission". Planetary and Space Science. 162: 207–215. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2018.02.011.

- "十年铸器,嫦娥五号这些年". mp.weixin.qq.com. 26 November 2020. Archived from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- Cai, Tingni. "Experimental Ground Validation of Spectral Quality of the Chang'E-5 Lunar Mineralogical Spectrometer". Spectroscopy and Spectral Analysis. 2019(1): 257–262.

- Xiao, Yuan; Su, Yan; Dai, Shun; Feng, Jianqing; Xing, Shuguo; Ding, Chunyu; Li, Chunlai (May 2019). "Ground experiments of Chang'e-5 lunar regolith penetrating radar". Advances in Space Research. 63 (10): 3404–3419. doi:10.1016/j.asr.2019.02.001.

- Li, Yuxi; Lu, Wei; Fang, Guangyou; Zhou, Bin; Shen, Shaoxiang (April 2019). "Performance verification of Lunar Regolith Penetrating Array Radar of Chang'e-5 mission". Advances in Space Research. 63 (7): 2267–2278. doi:10.1016/j.asr.2018.12.012.

- "PolyU-made space instruments complete lunar sampling for Chang'e 5".

- Foust, Jeff (25 September 2017). "Long March 5 failure to postpone China's lunar exploration program". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 16 March 2020. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- "Successful Long March 5 launch opens way for China's major space plans". SpaceNews. 27 December 2019. Archived from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- CNSA. "Chinese lunar mission reaches vital stage".

- Myers, Steven Lee; Chang, Kenneth (1 December 2020). "China Lands Chang'e-5 Spacecraft on Moon to Gather Lunar Rocks and Soil". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- Zhao, Jiannan; Xiao, Long; Qiao, Le; Glotch, Timothy D.; Huang, Qian (27 June 2017). "The Mons Rümker volcanic complex of the Moon: a candidate landing site for the Chang'e-5 mission". Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. 122 (7): 1419–1442. Bibcode:2017JGRE..122.1419Z. doi:10.1002/2016je005247. ISSN 2169-9097.

- Jolliff, Bradley L.; Gillis, Jeffrey J.; Haskin, Larry A.; Korotev, Randy L.; Wieczorek, Mark A. (25 February 2000). "Major lunar crustal terranes: Surface expressions and crust-mantle origins". Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. 105 (E2): 4197–4216. doi:10.1029/1999JE001103.

- Qian, Y. Q.; Xiao, L.; Zhao, S. Y.; Zhao, J. N.; Huang, J.; Flahaut, J.; Martinot, M.; Head, J. W.; Hiesinger, H.; Wang, G. X. (June 2018). "Geology and Scientific Significance of the Rümker Region in Northern Oceanus Procellarum: China's Chang'E-5 Landing Region". Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. 123 (6): 1407–1430. doi:10.1029/2018JE005595.

- Andrew Jones 3 December 2020. "China's Chang'e 5 probe lifts off from moon carrying lunar samples". Space.com. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- CNSA. "Chang'e 5 mission continues as ascender separates".

- "Chang'e-5 spacecraft smashes into moon after completing mission". SpaceNews. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- CNSA. "Chang'e 5 set to start journey to Earth".

- Jones, Andrew (14 December 2020). "China's Chang'e 5 moon lander is no more after successfully snagging lunar rocks". Space.com. Archived from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- CNSA. "Chang'e 5's reentry capsule lands with moon samples".

- Jones, Andrew (16 December 2020). "China recovers Chang'e-5 then takes the Moon samples after complex 23-day mission". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 16 December 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- Jonathan Amos (16 December 2020). "China's Chang'e-5 mission returns Moon samples". BBC News. Archived from the original on 16 December 2020. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- Amos, Jonathan. "China's Chang'e-5 mission returns Moon samples". BBC News. Archived from the original on 16 December 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- "China says it will share Chang'e 5 samples with global scientific community". South China Morning Post. 17 December 2020. Archived from the original on 17 December 2020. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- "Chinese Long March Rocket successfully launches Lunar Return Demonstrator". Spaceflight101.com. 23 October 2014. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- "China launches test return orbiter for lunar mission". Xinhuanet. 24 October 2014. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- "Chang'e 5 Test Mission Updates". Spaceflight101.com. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- "ESA tracks Chang'e-5 Moon mission". esa.int. European Space Agency. Archived from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- Bob McDonald (27 November 2020). "Chinese sample return mission to the moon harkens back to 1960s lunar race". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 8 December 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- DiMascio, Jen; Perrett, Bradley; Klotz, Irene (3 December 2020). "Podcast: How Chang'e 5 Fits into China's Space Program". Aviation Week Network. Archived from the original on 6 December 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- Simon Sharwood (17 December 2020). "China's Chang'e 5 probe lands Moon rocks in Inner Mongolia". The Register. Archived from the original on 18 December 2020. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

_on_Jul_14_2020_aligned_to_stars.jpg.webp)