China Zhi Gong Party

The China Zhi Gong Party (Chinese: 中国致公党; pinyin: Zhōngguó Zhìgōngdǎng; lit. 'Public Interest Party of China') is one of the eight legally recognised minor political parties in the People's Republic of China that are subservient to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and represented in the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, a principal organisation in the United Front.[7][8] Some scholars have described the Zhi Gong Party as "gathering non-party voices to support the party".[9]

China Zhi Gong Party | |

|---|---|

| Chairperson | Wan Gang |

| Founded | 10 October 1925 |

| Preceded by | Hongmen |

| Headquarters | Beijing, China |

| Newspaper | China Development[1] China Zhi Gong[2] |

| Membership (2016) | 48,000[3][4] |

| Ideology | Since 1947:[5][6] Marxism–Leninism Mao Zedong Thought Socialism with Chinese characteristics 1925–1947: Federalism Multi-party democracy |

| National affiliation | United Front |

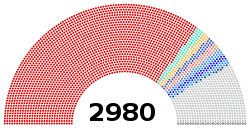

| National People's Congress | 38 / 2,980 |

| Standing Committee of NPC | 3 / 175 |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Website | |

| www | |

| China Zhi Gong Party | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中國致公黨 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中国致公党 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||

| Tibetan | ཀྲུང་གོ་ཀྲི་ཀུང་ཏང། | ||||||

| |||||||

| Zhuang name | |||||||

| Zhuang | Cunghgoz Ceiqgoeng Danj | ||||||

| Mongolian name | |||||||

| Mongolian Cyrillic | Дундад улсын зии хүн даан нам | ||||||

| Mongolian script | ᠳᠤᠮᠳᠠᠳᠤ ᠤᠯᠤᠰ ᠤᠨ ᡁᠢ ᠬᠦᠩ ᠳ᠋ᠠᠩ ᠨᠠᠮ | ||||||

| Uyghur name | |||||||

| Uyghur | جۇڭگو ئادالەتچىلەر پارتىيىسى | ||||||

| Manchu name | |||||||

| Manchu script | ᡷᡳᡳᡬᠣᠩᡩᠠᠩ | ||||||

| Romanization | Zhig'ongdang | ||||||

History

The China Zhi Gong Party derives from the overseas Hung Society organisation "Hung Society Zhigong Hall" or "Chee Kong Tong", based in San Francisco, United States. This organisation was one of the key supporters of Sun Yat-sen in his revolutionary efforts to overthrow the Qing dynasty.

The party was founded in October 1925 in San Francisco, and was led by Chen Jiongming and Tang Jiyao, two ex-Kuomintang warlords that went into opposition. Their first platform was federalism and multi-party democracy. The party moved its headquarters to Hong Kong in 1926. After the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931 it began engaging in anti-Japanese propaganda and boycotts. The party was nearly wiped out during the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong. The party turned to the left during its third party congress in 1947.

After the People's Republic of China was founded, at the invitation of the CCP, representatives of the CZGP attended the First Plenary Session of the CPPCC in 1949. They participated in drawing up the CPPCC Common Program and electing the Central People's Government. As part of the CCP's reorganisation of the minor aligned parties, the CZGP was designated as the party of returned overseas Chinese, their relatives, and noted figures and scholars who have overseas ties.

On occasions, the Zhi Gong Party appears to be used as an intermediary for contacts with certain foreign interests. For example, when a delegation of Paraguayan politicians visited Beijing in 2001 and met Li Peng (despite Paraguay having diplomatic relations not with PRC but with ROC in Taiwan), it was invited not by the PRC government or the CCP, but by the Zhi Gong Party.[10]

In April 2007, Wan Gang, Deputy Chair of the Zhi Gong Party Central Committee, was appointed Technology Minister of China. This was the first non-Communist Party ministerial appointment in China since the 1950s.

Leaders

- Chen Jiongming (1925–1933)

- Chen Yansheng (陈演生) (1933–1947)

- Li Jishen (1947–1950)

- Chen Qiyou (陈其尤) (1950–1979)

- Huang Dingchen (黄鼎臣) (1979–1984)

- Dong Yinchu (董寅初) (1984–1997)

- Luo Haocai (1997–2007)

- Wan Gang (2007–present)[11]

See also

References

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 27 December 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 January 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 December 2017. Retrieved 27 December 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- To, James Jiann Hua (15 May 2014). Qiaowu: Extra-Territorial Policies for the Overseas Chinese. BRILL. p. 80. ISBN 978-90-04-27228-6.

- Tatlow, Didi Kirsten (12 July 2019). "The Chinese Influence Effort Hiding in Plain Sight". The Atlantic. ISSN 1072-7825. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- Tatlow, Didi Kirsten; Feldwisch-Drentrup, Hinnerk; Fedasiuk, Ryan (3 August 2020), Hannas, William C.; Tatlow, Didi Kirsten (eds.), "Europe: A technology transfer mosaic", China’s Quest for Foreign Technology (1 ed.), Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge, 2021. |: Routledge, pp. 113–129, doi:10.4324/9781003035084-10, ISBN 978-1-003-03508-4CS1 maint: location (link)

- Chinese Top Legislator Meets Paraguayan Delegation Archived 5 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine (31 July 2001)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

.svg.png.webp)