Manchu alphabet

The Manchu alphabet (Manchu: ᠮᠠᠨᠵᡠ

ᡥᡝᡵᡤᡝᠨ; Möllendorff: manju hergen; Abkai: manju hergen) is the alphabet used to write the now nearly-extinct Manchu language. A similar script is used today by the Xibe people, who speak a language considered either as a dialect of Manchu or a closely related, mutually intelligible language. It is written vertically from top to bottom, with columns proceeding from left to right.

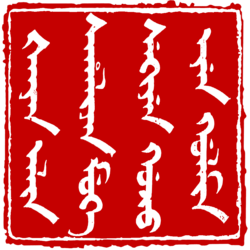

| Manchu script ᠮᠠᠨᠵᡠ ᡥᡝᡵᡤᡝᠨ manju hergen | |

|---|---|

Seal with Manchu text | |

| Type | |

| Languages | Manchu Xibe |

Parent systems | |

| Direction | Top-to-bottom |

| ISO 15924 | Mong, 145 |

Unicode alias | Mongolian |

| Chinese romanization |

|---|

| Mandarin |

| Wu |

| Yue |

| Min |

| Gan |

| Hakka |

| Xiang |

| See also |

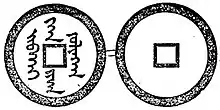

History

Tongki fuka akū hergen

According to the Veritable Records (Manchu: ᠮᠠᠨᠵᡠ ᡳ

ᠶᠠᡵᡤᡳᠶᠠᠨ

ᡴᠣᠣᠯᡳ; Möllendorff: manju i yargiyan kooli; Chinese: 滿洲實錄; pinyin: Mǎnzhōu Shílù), in 1599 the Jurchen leader Nurhaci decided to convert the Mongolian alphabet to make it suitable for the Manchu people. He decried the fact that while illiterate Han Chinese and Mongolians could understand their respective languages when read aloud, that was not the case for the Manchus, whose documents were recorded by Mongolian scribes. Overriding the objections of two advisors named Erdeni and G'ag'ai, he is credited with adapting the Mongolian script to Manchu. The resulting script was known as tongki fuka akū hergen (Manchu: ᡨᠣᠩᡴᡳ

ᡶᡠᡴᠠ

ᠠᡴᡡ

ᡥᡝᡵᡤᡝᠨ) — the "script without dots and circles".

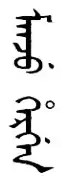

Tongki fuka sindaha hergen

In 1632, Dahai added diacritical marks to clear up a lot of the ambiguity present in the original Mongolian script; for instance, a leading k, g, and h are distinguished by the placement of no diacritical mark, a dot, and a circle, respectively. This revision created the standard script, known as tongki fuka sindaha hergen (Manchu: ᡨᠣᠩᡴᡳ

ᡶᡠᡴᠠ

ᠰᡳᠨᡩᠠᡥᠠ

ᡥᡝᡵᡤᡝᠨ) — the "script with dots and circles". As a result, the Manchu alphabet contains little ambiguity. Recently discovered manuscripts from the 1620s make clear, however, that the addition of dots and circles to Manchu script began before their supposed introduction by Dahai.

Dahai also added the tulergi hergen ("foreign/outer letters"): ten graphemes to facilitate Manchu to be used to write Chinese, Sanskrit, and Tibetan loanwords. Previously, these non-Manchu sounds did not have corresponding letters in Manchu.[1] Sounds that were transliterated included the aspirated sounds k' (Chinese pinyin: k, ᠺ), k (g, ᡬ), x (h, ᡭ); ts' (c, ᡮ); ts (ci, ᡮ᠊ᡟ); sy (si, ᠰ᠊ᡟ); dz (z, ᡯ); c'y (chi, ᡱᡟ); j'y (zhi, ᡷᡟ); and ž (r, ᡰ).[2]

19th century – present

By the middle of the nineteenth century, there were three styles of writing Manchu in use: standard script (ginggulere hergen), semi-cursive script (gidara hergen), and cursive script (lasihire hergen). Semicursive script had less spacing between the letters, and cursive script had rounded tails.[3]

The Manchu alphabet was also used to write Chinese. A modern example is in Manchu: a Textbook for Reading Documents, which has a comparative table of romanizations of Chinese syllables written in Manchu letters, Hànyǔ Pīnyīn and Wade–Giles.[4] Using the Manchu script to transliterate Chinese words is a source of loanwords for the Xibe language.[5] Several Chinese-Manchu dictionaries contain Chinese characters transliterated with Manchu script. The Manchu versions of the Thousand Character Classic and Dream of the Red Chamber are actually the Manchu transcription of all the Chinese characters.[6]

In the Imperial Liao-Jin-Yuan Three Histories National Language Explanation (欽定遼金元三史國語解 Qinding Liao Jin Yuan sanshi guoyujie) commissioned by the Qianlong Emperor, the Manchu alphabet is used to write Evenki (Solon) words. In the Pentaglot Dictionary, also commissioned by the Qianlong Emperor, the Manchu alphabet is used to transcribe Tibetan and Chagatai (related to Uyghur) words.

Alphabet

| Characters | Transliteration | Unicode | Notes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| isolated | initial | medial | final | ||||

| Vowels[7] | |||||||

| ᠠ | ᠠ᠊ | ᠊ᠠ᠊ | ᠊ᠠ | a [a] | 1820 | ||

| ᠊ᠠ᠋ | |||||||

| ᡝ | ᡝ᠊ | ᠊ᡝ᠊ | ᠊ᡝ | e [ə] | 185D | Second final form is used after k, g, h ([qʰ], [q], [χ]).[8] | |

| ᡝ᠋ | |||||||

| ᡳ | ᡳ᠊ | ᠊ᡳ᠊ | ᠊ᡳ | i [i] | 1873 | ||

| ᠊ᡳ᠋᠊ | ᠊ᡳ᠋ | ||||||

| ᠣ | ᠣ᠊ | ᠊ᠣ᠊ | ᠊ᠣ | o [ɔ] | 1823 | ||

| ᠊ᠣ᠋ | |||||||

| ᡠ | ᡠ᠊ | ᠊ᡠ᠊ | ᠊ᡠ | u [u] | 1860 | ||

| ?? | |||||||

| ᡡ | ᡡ᠊ | ᠊ᡡ᠊ | ᠊ᡡ | ū/uu/v [ʊ] | 1861 | ||

| ᠊ᡟ᠊ | ᠊ᡟ | y/y/i' [ɨ] | 185F | Used in Chinese loanwords. | |||

| ᡳᠣᡳ | ᡳᠣᡳ᠊ | ᠊ᡳᠣᡳ᠊ | ᠊ᡳᠣᡳ | ioi [y] | Used in Chinese loanwords. | ||

| Consonants[9] | |||||||

| ᠨ᠊ | ᠊ᠨ᠋᠊ | ᠊ᠨ ᠊ᠨ᠋ | n [n] | 1828 | First medial form is used before consonants; second is used before vowels | ||

| ᠊ᠨ᠊ | |||||||

| ᠊ᠩ᠊ | ᠊ᠩ | ng [ŋ] | 1829 | This form is used before consonants | |||

| ᡴ᠊ | ᠊ᡴ᠊ | ᠊ᡴ | k [qʰ] | 1874 | First medial form is used before a o ū; second is used before consonants | ||

| ᠊ᡴ᠋᠊ | |||||||

| ( |

᠊ᡴ᠌᠊ | ᠊ᡴ᠋ | k [kʰ] | This form is used before e, i, u. | |||

| ᡤ᠊ | ᠊ᡤ᠊ | g [q] | 1864 | This form is used after a, o, ū. | |||

| g [k] | This form is used after e, i, u. | ||||||

| ᡥ᠊ | ᠊ᡥ᠊ | h [χ] | 1865 | This form is used after a, o, ū. | |||

| h [x] | This form is used after e, i, u. | ||||||

| ᠪ᠊ | ᠊ᠪ᠊ | ᠊ᠪ | b [p] | 182A | |||

| ᡦ᠊ | ᠊ᡦ᠊ | p [pʰ] | 1866 | ||||

| ᠰ᠊ | ᠊ᠰ᠊ | ᠊ᠰ | s [s], [ɕ] before [i] | 1830 | |||

| ᡧ᠊ | ᠊ᡧ᠊ | š [ʃ], [ɕ] before [i] | 1867 | ||||

| ᡨ᠋᠊ | ᠊ᡨ᠋᠊ | t [tʰ] | 1868 |

First initial and medial forms are used before a, o, i; | |||

| ᠊ᡨ᠌᠊ | ᠊ᡨ | ||||||

| ᡨ᠌᠊ | ᠊ᡨ᠍᠊ | ||||||

| ᡩ᠊ | ᠊ᡩ᠊ | d [t] | 1869 |

First initial and medial forms are used before a, o, i; | |||

| ᡩ᠋᠊ | ᠊ᡩ᠋᠊ | ||||||

| ᠯ᠊ | ᠊ᠯ᠊ | ᠊ᠯ | l [l] | 182F | Initial and final forms usually exist in foreign words. | ||

| ᠮ᠊ | ᠊ᠮ᠊ | ᠊ᠮ | m [m] | 182E | |||

| ᠴ᠊ | ᠊ᠴ᠊ | c/ch/č/q [t͡ʃʰ], [t͡ɕʰ] before [i] | 1834 | ||||

| ᠵ᠊ | ᠊ᠵ᠊ | j/zh/ž [t͡ʃ], [t͡ɕ] before [i] | 1835 | ||||

| ᠶ᠊ | ᠊ᠶ᠊ | y [j] | 1836 | ||||

| ᡵ᠊ | ᠊ᡵ᠊ | ᠊ᡵ | r [r] | 1875 | Initial and final forms exist mostly in foreign words. | ||

| ᡶ | ᡶ | f [f] | 1876 | First initial and medial forms are used before a e; second initial and medial forms are used before i o u ū | |||

| ᡶ᠋ | ᡶ᠋ | ||||||

| ᠸ᠊ | ᠊ᠸ᠊ | v (w) [w], [v-] | 1838 | ||||

| ᠺ᠊ | ᠊ᠺ᠊ | k'/kk/k῾/k’ [kʰ] | 183A | Used for Chinese k [kʰ]. Used before a, o. | |||

| ᡬ᠊ | ᠊ᡬ᠊ | g'/gg/ǵ/g’ [k] | 186C | Used for Chinese g [k]. Used before a, o. | |||

| ᡭ᠊ | ᠊ᡭ᠊ | h'/hh/h́/h’ [x] | 186D | Used in Chinese h [x]. Used before a, o. | |||

| ᡮ᠊ | ᠊ᡮ᠊ | ts'/c/ts῾/c [tsʰ] | 186E | Used in Chinese c [t͡sʰ]. | |||

| ᡯ᠊ | ᠊ᡯ᠊ | dz/z/dz/z [t͡s] | 186F | Used in Chinese z [t͡s]. | |||

| ᡰ᠊ | ᠊ᡰ᠊ | ž/rr/ž/r’ [ʐ] | 1870 | Used in Chinese r [ʐ]. | |||

| ᡱ᠊ | ᠊ᡱ᠊ | c'/ch/c῾/c’ [tʂʰ] | 1871 | Used in Chinese ch [tʂʰ] and chi/c'y [tʂʰɨ] | |||

| ᡷ᠊ | ᠊ᡷ᠊ | j/zh/j̊/j’ [tʂ] | 1877 | Used in Chinese zh [tʂ] and zhi/j'y [tʂɨ] | |||

Method of teaching

Despite its alphabetic nature, the Manchu "alphabet" was traditionally taught as a syllabary to reflect its phonotactics. Manchu children were taught to memorize the shapes of all the syllables in the language separately as they learned to write[10] and say right away "la, lo", etc., instead of saying "l, a — la"; "l, o — lo"; etc. As a result, the syllables contained in their syllabary do not contain all possible combinations that can be formed with their letters. They made, for instance, no such use of the consonants l, m, n and r as English; hence if the Manchu letters s, m, a, r and t were joined in that order, a Manchu would not pronounce them as "smart".[11]

Today, it is still divided among experts on whether the Manchu script is alphabetic or syllabic. In China, it is considered syllabic, and Manchu is still taught in this manner, while in the West it is treated like an alphabet. The alphabetic approach is used mainly by foreigners who want to learn the language, as studying the Manchu script as a syllabary takes longer.[12][13]

Twelve uju

The syllables in Manchu are divided into twelve categories called uju (literally "head") based on their syllabic codas (final phonemes). [14][15][16] Here lists the names of the twelve uju in their traditional order:

a, ai, ar, an, ang, ak, as, at, ab, ao, al, am.

Each uju contains syllables ending in the coda of its name. Hence, Manchu only allows nine final consonants for its closed syllables, otherwise a syllable is open with a monophthong (a uju) or a diphthong (ai uju and ao uju).The syllables in an uju are further sorted and grouped into three or two according to their similarities in pronunciation and shape. For example, a uju arranges its 131 licit syllables in the following order:

a, e, i; o, u, ū; na, ne, ni; no, nu, nū;

ka, ga, ha; ko, go, ho; kū, gū, hū;

ba, be, bi; bo, bu, bū; pa, pe, pi; po, pu, pū;

sa, se, si; so, su, sū; ša, še, ši; šo, šu, šū;

ta, da; te, de; ti, di; to, do; tu, du;

la, le, li; lo, lu, lū; ma, me, mi; mo, mu, mū;

ca, ce, ci; co, cu, cū; ja, je, ji; jo, ju, jū; ya, ye; yo, yu, yū;

ke, ge, he; ki, gi, hi; ku, gu, hu; k'a, g'a, h'a; k'o, g'o, h'o;

ra, re, ri; ro, ru, rū;

fa, fe, fi; fo, fu, fū; wa, we;

ts'a, ts'e, ts; ts'o, ts'u; dza, dze, dzi, dzo, dzu;

ža, že, ži; žo, žu; sy, c'y, jy.

In general, while syllables in the same row resemble each other phonetically and visually, syllables in the same group (as the semicolons separate) bear greater similarities.

Punctuation

The Manchu alphabet has two kinds of punctuation: two dots (᠉), analogous to a period; and one dot (᠈), analogous to a comma. However, with the exception of lists of nouns being reliably punctuated by single dots, punctuation in Manchu is inconsistent, and therefore not of much use as an aid to readability.[17]

The equivalent of the question mark in Manchu script consists of some special particles, written at the end of the question.[18]

Jurchen script

The Jurchens of a millennium ago became the ancestors of the Manchus when Nurhaci united the Jianzhou Jurchens (1593–1618) and his son subsequently renamed the consolidated tribes as the "Manchu". Throughout this period, the Jurchen language evolved into what we know as the Manchu language. Its script has no relation to the Manchu alphabet, however. The Jurchen script was instead derived from the Khitan script, itself derived from Chinese characters.

Unicode

The Manchu alphabet is included in the Unicode block for Mongolian.

| Mongolian[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+180x | ᠀ | ᠁ | ᠂ | ᠃ | ᠄ | ᠅ | ᠆ | ᠇ | ᠈ | ᠉ | ᠊ | FV S1 |

FV S2 |

FV S3 |

MV S |

|

| U+181x | ᠐ | ᠑ | ᠒ | ᠓ | ᠔ | ᠕ | ᠖ | ᠗ | ᠘ | ᠙ | ||||||

| U+182x | ᠠ | ᠡ | ᠢ | ᠣ | ᠤ | ᠥ | ᠦ | ᠧ | ᠨ | ᠩ | ᠪ | ᠫ | ᠬ | ᠭ | ᠮ | ᠯ |

| U+183x | ᠰ | ᠱ | ᠲ | ᠳ | ᠴ | ᠵ | ᠶ | ᠷ | ᠸ | ᠹ | ᠺ | ᠻ | ᠼ | ᠽ | ᠾ | ᠿ |

| U+184x | ᡀ | ᡁ | ᡂ | ᡃ | ᡄ | ᡅ | ᡆ | ᡇ | ᡈ | ᡉ | ᡊ | ᡋ | ᡌ | ᡍ | ᡎ | ᡏ |

| U+185x | ᡐ | ᡑ | ᡒ | ᡓ | ᡔ | ᡕ | ᡖ | ᡗ | ᡘ | ᡙ | ᡚ | ᡛ | ᡜ | ᡝ | ᡞ | ᡟ |

| U+186x | ᡠ | ᡡ | ᡢ | ᡣ | ᡤ | ᡥ | ᡦ | ᡧ | ᡨ | ᡩ | ᡪ | ᡫ | ᡬ | ᡭ | ᡮ | ᡯ |

| U+187x | ᡰ | ᡱ | ᡲ | ᡳ | ᡴ | ᡵ | ᡶ | ᡷ | ᡸ | |||||||

| U+188x | ᢀ | ᢁ | ᢂ | ᢃ | ᢄ | ᢅ | ᢆ | ᢇ | ᢈ | ᢉ | ᢊ | ᢋ | ᢌ | ᢍ | ᢎ | ᢏ |

| U+189x | ᢐ | ᢑ | ᢒ | ᢓ | ᢔ | ᢕ | ᢖ | ᢗ | ᢘ | ᢙ | ᢚ | ᢛ | ᢜ | ᢝ | ᢞ | ᢟ |

| U+18Ax | ᢠ | ᢡ | ᢢ | ᢣ | ᢤ | ᢥ | ᢦ | ᢧ | ᢨ | ᢩ | ᢪ | |||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

References

- Gorelova, L: "Manchu Grammar", page 50. Brill, 2002.

- Gorelova, L: "Manchu Grammar", pages 71-72. Brill, 2002.

- Gorelova, L: "Manchu Grammar", page 72. Brill, 2002.

- Gertraude Roth Li (2000). Manchu: a textbook for reading documents. Hawaii, USA: University of Hawaii Press. p. 370. ISBN 978-0824822064. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

Manchu transliteration of Chinese syllables Some Chinese syllables are transliterated in different ways. There may be additional versions to those listed below. *W-G stands for Wade-Giles

- Gertraude Roth Li (2000). Manchu: a textbook for reading documents. Hawaii, USA: University of Hawaii Press. p. 294. ISBN 978-0824822064. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

f) Transliteration of Chinese words and compounds. Though most Chinese words in Manchu are easily recognizable to students familiar with Chinese, it is helpful to remember the most important rules that govern the transliteration of Chinese words into Manchu.

- Salmon, Claudine, ed. (2013). Literary Migrations: Traditional Chinese Fiction in Asia (17th-20th Centuries). 19 of Nalanda-Sriwijaya series (reprint ed.). Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 102. ISBN 978-9814414326. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- Gorelova, L: "Manchu Grammar", page 59. Brill, 2002.

- Gorelova, L: "Manchu Grammar", page 53. Brill, 2002.

- Gorelova, L: "Manchu Grammar", page 70. Brill, 2002.

- Saarela 2014, p. 169.

- Meadows 1849, p. 3.

- Gertraude Roth Li (2000). Manchu: a textbook for reading documents. University of Hawaii Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0824822064. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

Alphabet: Some scholars consider the Manchu script to be a syllabic one.

- Gertraude Roth Li (2010). Manchu: A Textbook for Reading Documents (Second Edition) (2 ed.). Natl Foreign Lg Resource Ctr. p. 16. ISBN 978-0980045956. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

Alphabet: Some scholars consider the Manchu script to be a syllabic one. Others see it as having an alphabet with individual letters, some of which differ according to their position within a word. Thus, whereas Denis Sinor urged in favor of a syllabic theory, Louis Ligeti preferred to consider the Manchu script an alphabetical one.

- Translation of the Ts'ing wan k'e mung, a Chinese Grammar of the Manchu Tartar Language; with introductory notes on Manchu Literature: (translated by A. Wylie.). Mission Press. 1855. pp. xxvii–.

- Shou-p'ing Wu Ko (1855). Translation (by A. Wylie) of the Ts'ing wan k'e mung, a Chinese grammar of the Manchu Tartar language (by Woo Kĭh Show-ping, revised and ed. by Ching Ming-yuen Pei-ho) with intr. notes on Manchu literature. pp. xxvii–.

- http://www.dartmouth.edu/~qing/WEB/DAHAI.html

- Li, G: "Manchu: A Textbook for Reading Documents", page 21. University of Hawai'i Press, 2000.

- Gorelova, L: "Manchu Grammar", page 74. Brill, 2002.

Further reading

- Saarela, Marten Soderblom (2020). The Early Modern Travels of Manchu: A Script and Its Study in East Asia and Europe. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-9693-8.

External links

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Manchu |