Christianization of Kievan Rus'

The Christianization of Kievan Rus' took place in several stages. In early 867, Patriarch Photius of Constantinople announced to other Christian patriarchs that the Rus', baptized by his bishop, took to Christianity with particular enthusiasm. Photius's attempts at Christianizing the country seem to have entailed no lasting consequences, since the Primary Chronicle and other Slavonic sources describe the tenth-century Rus' as firmly entrenched in paganism. Following the Primary Chronicle, the definitive Christianization of Kievan Rus' dates from the year 988 (the year is disputed[1]), when Vladimir the Great was baptized in Chersonesus and proceeded to baptize his family and people in Kiev. The latter events are traditionally referred to as baptism of Rus' (Russian: Крещение Руси, Ukrainian: Хрещення Русі) in Ukrainian and Russian literature.

Prehistory

According to the Church Tradition, Christianity was first brought to the territory of modern Belarus, Russia and Ukraine by Saint Andrew, the first Apostle of Jesus Christ. He traveled over the Black Sea to the Greek colony of Chersonesus Taurica in Crimea, where he converted several thousand men to the new faith. Allegedly Saint Andrew traveled also north along the Dnieper River, where Kiev would be founded around the 5th century, and as far north as the future location of Veliky Novgorod. The legendary account of the Rus'ian Primary Chronicle tells that Saint Andrew was amused by the Slavic customs of washing in hot steam bath, banya, on his way.

North Pontic Greek colonies, both in Crimea and on the modern Ukrainian shores of the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea, remained the main centers of Christianity in Eastern Europe for almost a thousand years. Notable Christian locations there include the Inkerman Cave Monastery, a medieval Byzantine monastery where the relics of St. Clement, the fourth Bishop of Rome, were supposedly kept before their removal to San Clemente by Saints Cyril and Methodius.

Saints Cyril and Methodius were the missionaries of Christianity among the Slavic peoples of Bulgaria, Great Moravia and Pannonia. Through their work they influenced the cultural development of all Slavs, for which they received the title "Apostles to the Slavs". They are credited with devising the Glagolitic alphabet, the first alphabet used to transcribe Old Church Slavonic,[2] Later on their students created the Cyrillic script in the First Bulgarian Empire used now in many Slavic countries, including Russia. After their deaths, their pupils continued their missionary work among other Slavs. Both brothers are venerated in the Ukrainian Catholic and Byzantine Catholic Churches as well as the Orthodox Church as saints with the title of "equal-to-apostles".

Ninth century

| Part of a series on the |

| Eastern Orthodox Church |

|---|

| Overview |

The most authoritative source for the early Christianization of Rus' is an encyclical letter of Patriarch Photius, datable to early 867. Referencing the Siege of Constantinople of 860, Photius informs the Oriental patriarchs and bishops that, after the Bulgarians turned to Christ in 863,[3] the Rus' followed suit. As was the case with the Bulgarians, the Patriarch found it prudent to send to the barbarians a bishop from Constantinople.[4]

With some modifications, the story is repeated by Constantine VII in De Administrando Imperio, followed by several generations of Byzantine historians, including John Skylitzes and Joannes Zonaras. That the imperial court and patriarchate regarded the 10th-century Rus' as Christians is evident from the fact that the bishopric of Rus' was enumerated in the lists of Christian sees, compiled during the reigns of Leo the Wise and Constantine VII. There is also an argumentum ex silentio: no Greek source recorded the second baptism of the Rus in the 990s.

Tenth century

Whatever the scope of Photius's efforts to Christianize the Rus', their effect was not lasting. Although they fail to mention the mission of Photius, the authors of the Primary Chronicle were aware that a sizable portion of the Kievan population was Christian by 944. In the Russo-Byzantine Treaty, preserved in the text of the chronicle, the Christian part of the Rus' swear according to their faith, while the ruling prince and other non-Christians invoke Perun and Veles after the pagan custom. The Kievan collegiate church of St. Elijah (whose cult in the Slavic countries was closely modeled on that of Perun) is mentioned in the text of the chronicle, leaving modern scholars to ponder how many churches existed in Kiev at the time.

Either in 945 or 957, the ruling regent, Olga of Kiev, visited Constantinople with a certain priest, Gregory. Her reception at the imperial court is described in De Ceremoniis. According to legends, Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII fell in love with Olga; however, she found a way to refuse him by tricking him to become her godfather. When she was baptized, she said it was inappropriate for a godfather to marry his goddaughter.

Although it is usually presumed that Olga was baptized in Constantinople rather than Kiev, there is no explicit mention of the sacrament, so neither version is excluded. Olga is also known to have requested a bishop and priests from Rome.[5] Her son, Sviatoslav (r. 963-972), continued to worship Perun and other gods of the Slavic pantheon. He remained a stubborn pagan all of his life; according to the Primary Chronicle, he believed that his warriors would lose respect for him and mock him if he became a Christian.

Sviatoslav's successor, Yaropolk I (r. 972-980), seems to have had a more conciliatory attitude towards Christianity. Late medieval sources even claim that Yaropolk exchanged ambassadors with the Pope. The Chronicon of Adémar de Chabannes and the life of St. Romuald (by Pietro Damiani) actually document the mission of St. Bruno of Querfurt to the land of Rus', where he succeeded in converting to Christianity a local king (one of three brothers who ruled the land). Alexander Nazarenko suggests that Yaropolk went through some preliminary rites of baptism, but was murdered at the behest of his pagan half-brother Vladimir (whose own rights to the throne were questionable) before his conversion was formalized. Following this theory, any information on Yaropolk's baptism according to the Latin rite would be suppressed by the later Orthodox chroniclers, zealous to keep Vladimir's image of the Rus Apostle untarnished for succeeding generations.[6]

Vladimir's baptism of Kiev

Background

During the first decade of Vladimir's reign, pagan reaction set in. Perun was chosen as the supreme deity of the Slavic pantheon and his idol was placed on the hill by the royal palace. This revival of paganism was contemporaneous with similar attempts undertaken by Jarl Haakon in Norway and (possibly) Svein Forkbeard in Denmark. His religious reform failed. By the late 980s he had found it necessary to adopt monotheism from abroad.

The Primary Chronicle reports that, in the year 986, Vladimir met with representatives from several religions. The result is amusingly described in the following apocryphal anecdote. Upon the meeting with Muslim Bulgarians of the Volga, Vladimir found their religion unsuitable due to its requirement to circumcise and taboos against alcoholic beverages and pork; supposedly, Vladimir said on that occasion: "Drinking is the joy of the Rus." He also consulted with Jewish envoys (who may or may not have been Khazars), questioned them about Judaism but ultimately rejected it, saying that their loss of Jerusalem was evidence of their having been abandoned by God.[7]

In the year 987, as the result of a consultation with his boyars, Vladimir sent envoys to study the religions of the various neighboring nations whose representatives had been urging him to embrace their respective faiths. Of the Muslim Bulgarians of the Volga the envoys reported there is no joy among them; only sorrow and a great stench. In the gloomy churches of the Germans his emissaries saw no beauty; but at Hagia Sophia, where the full festival ritual of the Byzantine Church was set in motion to impress them, they found their ideal: "We no longer knew whether we were in heaven or on earth," they reported, "nor such beauty, and we know not how to tell of it."[8]

Baptism of Vladimir

Foreign sources, very few in number, present the following story of Vladimir's conversion. Yahya of Antioch and his followers (al-Rudhrawari, al-Makin, Al-Dimashqi, and ibn al-Athir)[9] give essentially the same account. In 987, the generals Bardas Sclerus and Bardas Phocas revolted against the Byzantine emperor Basil II. Both rebels briefly joined forces and advanced on Constantinople. On September 14, 987, Bardas Phocas proclaimed himself emperor. Anxious to avoid the siege of his capital, Basil II turned to the Rus' for assistance, even though they were considered enemies at that time. Vladimir agreed, in exchange for a marital tie; he also agreed to accept Christianity as his religion and bring his people to the new faith. When the wedding arrangements were settled, Vladimir dispatched 6,000 troops to the Byzantine Empire and they helped to put down the revolt.[10]

In the Primary Chronicle, the account of Vladimir's baptism is preceded by the so-called Korsun' Legend. According to this apocryphal story, in 988 Vladimir captured the Greek town of Korsun' (Chersonesus) in Crimea, highly important commercially and politically. This campaign may have been dictated by his wish to secure the benefits promised to him by Basil II, when he had asked for the Rus' assistance against Phocas. In recompense for the evacuation of Chersonesos, Vladimir was promised the hand of the emperor's sister, Anna Porphyrogenita. Prior to the wedding, Vladimir was baptized (either in Chersonesos or in Kiev), taking the Christian name of Basil out of compliment to his imperial brother-in-law. The sacrament was followed by his marriage with the Byzantine princess.[11] The alleged place of Vladimir's baptism in Chersonesos is marked by St. Vladimir's Cathedral.

Baptism of Kiev

Returning to Kiev in triumph, Vladimir exhorted the residents of his capital to the Dnieper river for baptism. This mass baptism became the iconic inaugural event in the Christianization of the state of Kievan Rus'.

At first Vladimir baptized his twelve sons and many boyars. He destroyed the wooden statues of Slavic pagan gods (which he had himself raised just eight years earlier). They were either burnt or hacked into pieces, and the statue of Perun — the supreme god — was thrown into the Dnieper.[12]

Then Vladimir sent a message to all residents of Kiev, "rich, and poor, and beggars, and slaves", to come to the river on the following day, lest they risk becoming the "prince's enemies". Large numbers of people came; some even brought infants with them. They were sent into the water while priests, who came from Chersonesos for the occasion, prayed.[13]

To commemorate the event, Vladimir built the first stone church of Kievan Rus', called the Church of the Tithes, where his body and the body of his new wife were to repose. Another church was built on top of the hill where pagan statues stood before.[14]

Aftermath

The baptism of Kiev was followed by similar ceremonies in other urban centres of the country. The Ioakim Chronicle says that Vladimir's uncle, Dobrynya, forced the Novgorodians into Christianity "by fire", while the local mayor, Putyata, persuaded his compatriots to accept Christian faith "by the sword". At that same time, Bishop Ioakim Korsunianin built the first, wooden, Cathedral of Holy Wisdom "with 13 tops" on the site of a pagan cemetery.[15]

Paganism persisted in the country for a long time, surfacing during the Upper Volga Uprising and other occasional pagan protests. The northeastern part of the country, centred on Rostov, was particularly hostile to the new religion. Novgorod itself faced a pagan uprising as late as 1071, in which Bishop Fedor faced a real threat to his person; Prince Gleb Sviatoslavich broke up the crowd by chopping a sorcerer in half with an axe.[16]

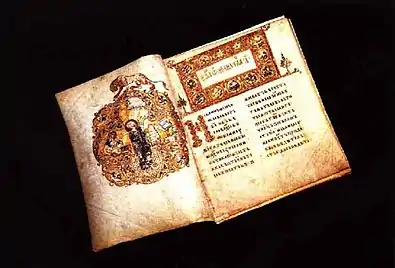

The Christianization of Rus firmly allied it with the Byzantine Empire. The Greek learning and book culture was adopted in Kiev and other centres of the country. Churches started to be built on the Byzantine model. During the reign of Vladimir's son Yaroslav I, Metropolitan Ilarion authored the first known work of East Slavic literature, an elaborate oration in which he favourably compared Rus to other lands known as the "Sermon on Law and Grace". The Ostromir Gospels, produced in Novgorod during the same period, was the first dated East Slavic book fully preserved. But the only surviving work of lay literature, The Tale of Igor's Campaign, indicates that a degree of pagan worldview remained under Christian Kievan Rus'.

In 1988, the faithful of the Eastern Catholic and Orthodox churches which have roots in the baptism of Kiev celebrated a millennium of Eastern Slavic Christianity. The great celebrations in Moscow changed the character of relationship between the Soviet state and the church. For the first time since 1917, numerous churches and monasteries were returned to the Russian Orthodox Church. In Ukrainian communities around the world, members of various Ukrainian churches also celebrated the Millennium of Christianity in Ukraine.

In 2008 the National Bank of Ukraine issued into circulation commemorative coins "Christianization of Kievan Rus" within "Rebirth of the Christian Spirituality in Ukraine" series.[17]

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Christianization of Rus. |

- Oleg Rapov, Russkaya tserkov v IX–pervoy treti XII veka (The Russian Church from the 9th to the First 3rd of the 12th Century). Moscow, 1988.

- Liturgy of the Hours, Volume III, 14 February.

- History of the Bulgarians from Antiquity to the 16th Century by Georgi Bakalov (2003) ISBN 954-528-289-4

- Photii Patriarchae Constantinopolitani Epistulae et Amphilochia. Eds.: B. Laourdas, L. G. Westerinck. T.1. Leipzig, 1983. P. 49.

- Thietmar of Merseburg says that the first archbishop of Magdeburg, Adalbert of Prague, before being promoted to this high rank, was sent by Emperor Otto to the country of the Rus (Rusciae) as a simple bishop but was expelled by pagans. The same data is duplicated in the annals of Quedlinburg and Hildesheim, among others.

- Alexander Nazarenko. Древняя Русь на международных путях. Moscow, 2001. ISBN 5-7859-0085-8.

- Primary Chronicle, year 6494 (986)

- Primary Chronicle, year 6495 (987)

- Ibn al-Athir dates these events to 985 or 986.

- Golden, P.B. (2006) "Rus." Encyclopaedia of Islam (Brill Online). Eds.: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C. E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill.

- Lavrentevskaia Letopis, also called the Povest Vremennykh Let, in Polnoe Sobranie Russkikh Letopisey (PSRL), vol. 1, col.s 95-102.

- Longsworth, Philip (2006). Russia: The Once and Future Empire from Pre-History to Putin. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 38. ISBN 0-312-36041-X.

- Lavrent. (PSRL 1), col. 102.

- Lavrent. (PSRL 1), cols. 108-109.

- Novgorodskaia tretiaia letopis, (PSRL 3), 208. On the initial conversion, see Vasilii Tatishchev, Istoriia rossiiskaia, A. I. Andreev, et al., eds. (Moscow and Leningrad: AN SSSR, 1962), vol. 1, pp. 112-113.

- Arsennii Nasonov, ed. Novgorodskaia Pervaia Letopis: Starshego i mladshego izvodov (Moscow and Leningrad: AN SSSR, 1950), pp. 191-96.

- Commemorative Coins "Christianization of Kievan Rus", National Bank of Ukraine web-site, July 2008