Volga Bulgaria

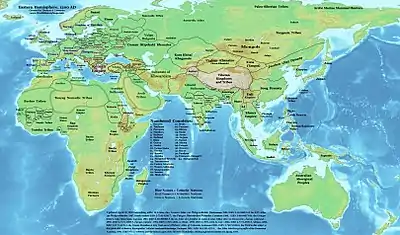

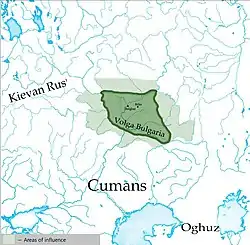

Volga Bulgaria (Tatar: Идел Болгар, Chuvash: Атӑлҫи Пӑлхар) or Volga–Kama Bulghar, was a historic Bulgar[2][3][4] state that existed between the 7th and 13th centuries around the confluence of the Volga and Kama River, in what is now European Russia. Volga Bulgaria was a multi-ethnic state with large numbers of Turkic Bulgars, a variety of Finnic and Ugric peoples, and many East Slavs.[5] The very strategic position of Volga Bulgaria allowed it to create a monopoly between the trade of Arabs, Norse and Avars.[6]

Volga Bulgaria | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7th century–1240s | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Capital | Bolghar Bilär | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Bulgar, Turki[1] | ||||||||||

| Religion | Tengrism, later Islam (after Almish Iltäbär) | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Ruler, Emir | |||||||||||

• 9th century | Kotrag, Irhan, Tuqyi, Aidar, Şilki, Batyr-Mumin | ||||||||||

• 10th-12th centuries | Almish Yiltawar, Mikail ibn Jafar, Ahmad ibn Jafar, Ghabdula ibn Mikail, Talib ibn Ahmad, Mumin ibn al-Hassan, Mumin ibn Ahmad, Abd ar-Rahman ibn Mumin, Abu Ishak Ibrahim ibn Mohammad, Nazir ad-Din | ||||||||||

• 13th century | Ghabdula Chelbir | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||

• Established | 7th century | ||||||||||

• Conversion to Islam | 922 | ||||||||||

| 1240s | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Tatarstan |

|

History

Origin and creation of the state

Information from first-hand sources on Volga Bulgaria is rather sparse. As no authentic Bulgar records have survived, most of our information comes from contemporary Arabic, Persian, Indo-Aryan or Russian sources. Some information is provided by excavations. It is believed the territory of Volga Bulgaria was originally settled by Finno-Ugric peoples, including Mari people.

The original Bulgars were Turkic tribes of Oghur origin,[7][8] who settled north of the Black Sea. During their westward migration across the Eurasian steppe, they came under the overlordship of the Khazars, leading other ethnic groups, including Finno-Ugric and Iranic peoples.[7] About 630 they founded Old Great Bulgaria which was destroyed by the Khazars in 668. Kubrat's son and appointed heir Batbayan Bezmer moved from the Azov region in about AD 660, commanded by the Kazarig Khagan Kotrag to whom he had surrendered. They reached Idel-Ural in the eighth century, where they became the dominant population at the end of the 9th century, uniting other tribes of different origin which lived in the area.[9] Some Bulgar tribes, however, continued westward and eventually settled along the Danube River, in what is now known as Bulgaria proper, where they created a confederation with the Slavs, adopting a South Slavic language and the Eastern Orthodox faith.

Most scholars agree that the Volga Bulgars were initially subject to the Khazarian Khaganate. This fragmented Volga Bulgaria grew in size and power and gradually freed from the influence of the Khazars. Sometime in the late 9th century unification processes started, and the capital was established at Bolghar (also spelled Bulgar) city, 160 km south from modern Kazan. However complete independence was reached after Khazaria's destruction and conquest by Sviatoslav in the late 10th century, thus Bulgars no longer paid tribute to it.[10][11]

Abu al-Ghazi Bahadur named the Volga Bulgar people as Ulak.[12]

Conversion to Islam and further statehood

Volga Bulgaria adopted Islam in 922 – 66 years before the Christianization of Kievan Rus'. In 921 Almış sent an ambassador to the Caliph requesting religious instruction. Next year an embassy returned with Ibn Fadlan as secretary. A significant number of Muslims already lived in the country.[13]

The Volga Bulgars attempted to convert Vladimir I of Kiev to Islam; however Vladimir rejected the notion of Rus' giving up wine, which he declared was the "very joy of their lives".[14]

Commanding the Volga River in its middle course, the state controlled much of trade between Europe and Asia prior to the Crusades (which made other trade routes practicable). The capital, Bolghar, was a thriving city, rivalling in size and wealth with the greatest centres of the Islamic world. Trade partners of Bolghar included from Vikings, Bjarmland, Yugra and Nenets in the north to Baghdad and Constantinople in the south, from Western Europe to China in the East. Other major cities included Bilär, Suar (Suwar), Qaşan (Kashan) and Cükätaw (Juketau). Modern cities Kazan and Yelabuga were founded as Volga Bulgaria's border fortresses. Some of the Volga Bulgarian cities still have not been found, but they are mentioned in old East Slavic sources. They are: Ashli (Oshel), Tuxçin (Tukhchin), İbrahim (Bryakhimov), Taw İle. Some of them were ruined during and after the Golden Horde invasion.

The Rus' principalities to the west posed the only tangible military threat. In the 11th century, the country was devastated by several raids by other Rus'. Then, at the turn of the 12th and 13th centuries, the rulers of Vladimir (notably Andrew the Pious and Vsevolod III), anxious to defend their eastern border, systematically pillaged Volga Bulgarian cities. Under Russian pressure from the west, the Volga Bulgars had to move their capital from Bolghar to Bilär.

Decline

In September 1223 near Samara an advance guard of Genghis Khan's army under command of Uran, son of Subutai Bahadur, entered Volga Bulgaria but was defeated in the Battle of Samara Bend. In 1236, the Mongols returned and in five years had subjugated the whole country, which at that time was suffering from internal war . Henceforth Volga Bulgaria became a part of the Ulus Jochi, later known as the Golden Horde. It was divided into several principalities; each of them became a vassal of the Golden Horde and received some autonomy. By the 1430s, the Khanate of Kazan was established as the most important of these principalities.

Demographics

A large part of the region's population included Turkic groups such as Sabirs, Barsil, Bilars, Baranjars, and part of the obscure[15] Burtas (by ibn Rustah). Modern Chuvashes claim to descend from Sabirs and Kazan Tatars from the Volga Bulgars.[16]

Another part comprised Volga Finnic and Magyar (Asagel and Pascatir) tribes, from which Bisermäns probably descend.[17] Ibn Fadlan refers to Volga Bulgaria as Saqaliba, a general Arabic term for Slavic people. Other researches tie the term to the ethnic name Scythian (or Saka in Persian).[18]

According to some historians, over 80% of the country's population was killed during the invasion. The remaining population mostly relocated to the northern areas (territories of modern Chuvashia and Tatarstan). Some autonomous duchies appeared in those areas. The steppe areas of Volga Bulgaria may have been settled by nomadic Kipchaks and Mongols, and the agricultural development suffered a severe decline.

Over time, the cities of Volga Bulgaria were rebuilt and became trade and craft centers of the Golden Horde. Some Volga Bulgars, primarily masters and craftsmen, were forcibly moved to Sarai and other southern cities of the Golden Horde. Volga Bulgaria remained a center of agriculture and handicraft.

Gallery

See also

- Timeline of Turks (500-1300)

- Atil

- Balymer

- Khanate of Kazan

- Qol Ghali

- Battle of Samara Bend

- Tatars

- Old Great Bulgaria

- Huns

References

- Название лит. языка XI - XIV вв., употреблявшегося в Дешт-и-Кипчак и Среднем Поволжье; сложился на базе хорезмско-тюрксого литературного языка и местных диалектов. От поволжского тюрки развился старотатарский литературный язык. Татарский энциклопедический словарь - с. 440

- Nicolle, David (2013). Armies of the Volga Bulgars & Khanate of Kazan. p. 14.

- Champion, Timothy (2014). Nationalism and Archaeology in Europe. p. 227.

- Koesel, Karrie J. (2014). Religion and Authoritarianism: Cooperation, Conflict, and the Consequences. p. 103.

- The New Cambridge medieval history. McKitterick, Rosamond. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. 1995–2005. ISBN 9781139055727. OCLC 697957877.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Popovski, Ivan (2017-05-10). A Short History of South East Europe. Lulu Press, Inc. ISBN 9781365953941.

- Golden 1992, p. 253, 256: "With their Avar and Türk political heritage, they assumed political leadership over an array of Turkic groups, Iranians and Finno-Ugric peoples, under the overlordship of the Khazars, whose vassals they remained." ... "The Bulgars, whose Oguric ancestors ..."

- Hyun Jin Kim (2013). The Huns, Rome and the Birth of Europe. Cambridge University Press. pp. 58–59, 150–155, 168, 204, 243. ISBN 9781107009066.

- "Болгарлар". Tatar Encyclopaedia (in Tatar). Kazan: The Republic of Tatarstan Academy of Sciences. Institution of the Tatar Encyclopaedia. 2002.

- A History of Russia: Since 1855, Walter Moss, pg 29

- Shpakovsky, Viacheslav; Nicolle, David (2013). Armies of the Volga Bulgars & Khanate of Kazan: 9th–16th centuries. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-78200-080-8.

- Makkay, János (2008), "Siculica Hungarica De la Géza Nagy până la Gyula László" [Siculica Hungarica From Géza Nagy to Gyula László] (PDF), Acta Siculica: 209–240

- Azade-Ayse Rolich, The Volga Tatars, 1986, page 11. Richard Frye, Ibn Fadlan's Journey to Russia, 2005, page 44 gives 16 May 922 for the first meeting with the ruler. This seems to be the official date of the conversion.

- The preaching of Islam: a history of the propagation of the Muslim faith By Sir Thomas Walker Arnold, p. 201-202

- RUSSIAN: "По этнокультурному определению буртас в результате двухсотлетнего изучения сложилось множество точек зрения, которые можно объединить в 3 основные: тюркская, аланская и мордовская (наименее распространённая)." Буртасы//Ислам в центрально-европейской части России: энциклопедический словарь / Коллект. автор; сост. и отв. редактор Д. З. Хайретдинов. — М.: Издательский дом «Медина», 2009, С.55. ENGLISH: "According to the ethnocultural definition of Burtas, as a result of two hundred years of study, many points of view have developed that can be combined into 3 main ones: Turkic, Alanian and Mordovian (the least common)." Burtases//Islam in the Central European part of Russia: an encyclopedic dictionary / Collect. author; comp. and otv. editor D.Z. Khairetdinov. - M .: Publishing house "Medina", 2009, p. 55.

- "Volga Bulgaria". Chuvash Encyclopedia. Chuvash Institute of Humanities. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- К вопросу о происхождении самоназвания бесермян УДМУРТОЛОГИЯ

- R. Frye, 2005. "Ibn Fadlan's journey to Russia"

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Volga Bulgaria. |

- (in Russian) Bariev, R(iza) X. 2005. Волжские Булгары : история и культура (Volga Bulgars: History and Culture). Saint Petersburg: Agat.