1912 United States presidential election

The 1912 United States presidential election was the 32nd quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 5, 1912. Democratic Governor Woodrow Wilson unseated incumbent Republican President William Howard Taft and defeated former President Theodore Roosevelt, who ran under the banner of the new Progressive or "Bull Moose" Party.[2][3] As of 2021, this is the most recent presidential election in which the second-place candidate was neither a Democrat nor a Republican.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

531 members of the Electoral College 266 electoral votes needed to win | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 58.8%[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

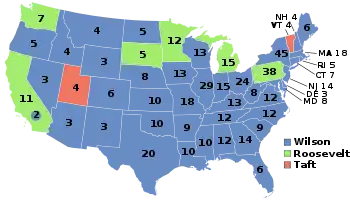

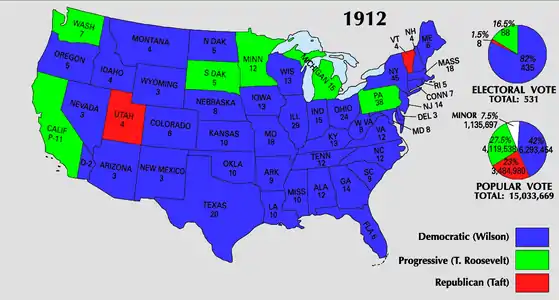

Presidential election results map. Blue denotes those won by Wilson/Marshall, light green denotes those won by Roosevelt/Johnson, red denotes states won by Taft/Butler. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

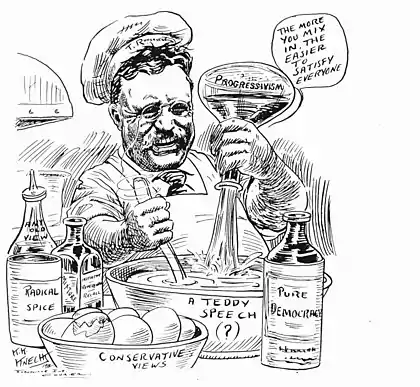

Roosevelt served as president from 1901 to 1909 as a Republican, and Taft succeeded him with his support. However, Taft's actions as President displeased Roosevelt, and Roosevelt challenged Taft for the party nomination at the 1912 Republican National Convention. When Taft and his conservative allies narrowly prevailed, Roosevelt rallied his progressive supporters and launched a third-party bid. At the Democratic Convention, Wilson won the presidential nomination on the 46th ballot, defeating Speaker of the House Champ Clark and several other candidates with the support of William Jennings Bryan and other progressive Democrats. The Socialist Party renominated its perennial standard-bearer, Eugene V. Debs.

The general election was bitterly contested by Wilson, Roosevelt, and Taft. Roosevelt's "New Nationalism" platform called for social insurance programs, reduction to an eight-hour workday, and robust federal regulation of the economy. Wilson's "New Freedom" platform called for tariff reduction, banking reform, and new antitrust regulation. With little chance of victory, Taft conducted a subdued campaign based on his platform of "progressive conservatism." Debs claimed the three candidates were financed by trusts and tried to galvanize support behind his socialist policies.

Wilson took advantage of the Republican split, winning 40 states and a large majority of the electoral vote with just 41.8% of the popular vote, the lowest support for any President after 1860. Wilson was the first Democrat to win a presidential election since 1892 and one of just two Democratic presidents to serve between 1861 (the American Civil War) and 1932 (the onset of the Great Depression). Roosevelt finished second with 88 electoral votes and 27% of the popular vote. Taft carried 23% of the national vote and won two states, Vermont and Utah. He was the first Republican to lose the Northern states. Debs won no electoral votes but took 6% of the popular vote, which remains the highest ever for a Socialist candidate as of 2021. With Wilson's decisive victory, he became the first presidential candidate to receive over 400 electoral votes in a presidential election.

Background

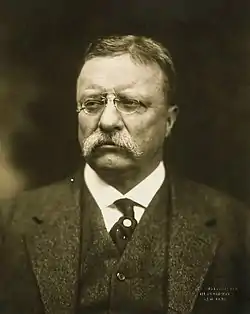

Republican President Theodore Roosevelt had declined to run for re-election in 1908 in fulfillment of a pledge to the American people not to seek a third term.[lower-alpha 2] Roosevelt had tapped Secretary of War William Howard Taft to become his successor, and Taft defeated William Jennings Bryan in the 1908 general election.

Republican Party split

During Taft's administration, a rift developed between Roosevelt and Taft, and they became the leaders of the Republican Party's two wings: progressives led by Roosevelt and conservatives led by Taft. Progressives favored labor restrictions protecting women and children, promoted ecological conservation, and were more sympathetic toward labor unions. They also favored the popular election of federal and state judges over appointment by the President or governors. Conservatives supported high tariffs to encourage domestic production, but favored business leaders over labor unions and were generally opposed to the popular election of judges.

Cracks in the party began to show when Taft supported the Payne–Aldrich Tariff Act in 1909.[4] The Act favored the industrial Northeast and angered the Northwest and South, where demand was strong for tariff reductions.[5] Early in his term, President Taft had promised to stand for a lower tariff bill, but protectionism had been a major policy of the Republican Party since its founding.[6]

Taft also abandoned Roosevelt's antitrust policy.[7] While Roosevelt believed some monopolies should be preserved, Taft argued that all monopolies must be broken up. Taft also fired popular conservationist Gifford Pinchot as head of the Bureau of Forestry in 1910.[8] By 1910, the split within the party was deep, and Roosevelt and Taft turned against one another despite their personal friendship. That summer, Roosevelt began a national speaking tour, during which he outlined his progressive philosophy and the New Nationalist platform, which he introduced in a speech in Osawatomie, Kansas on August 31.[9] In the 1910 midterm elections, the Republicans lost 57 seats in the House of Representatives as the Democrats gained a majority for the first time since 1894. These results were a large defeat for the conservative wing of the party.[10] James E. Campbell writes that one cause may have been a large number of progressive voters choosing third-party candidates over conservative Republicans.[11] Nevertheless, Roosevelt continued to reject calls to run for president into the year 1911. In a January letter to newspaper editor William Allen White, he wrote, "I do not think there is one chance in a thousand that it will ever be wise to have me nominated."[12] However, speculation continued, further harming Roosevelt and Taft's relationship. After months of continually increasing support, Roosevelt changed his position, writing to journalist Henry Beach Needham in January 1912 that if the nomination "comes to me as a genuine public movement of course I will accept."[13]

Nominations

Republican Party nomination

| William Howard Taft | James S. Sherman | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 27th President of the United States (1909–1913) |

27th Vice President of the United States (1909–1912) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Candidates gallery

Delegate selection

For the first time, many convention delegates were elected in presidential preference primaries. Progressive Republicans advocated primary elections as a way of breaking the control of political parties by bosses. Altogether, twelve states held Republican primaries.

Senator Robert M. La Follette won two of the first four primaries (North Dakota and his home state of Wisconsin), but Taft won a major victory in Roosevelt's home state of New York and continued to rack up delegates in more conservative, traditional state conventions.

However, on March 28, Roosevelt issued an ultimatum: if Republicans did not nominate him, he would run as an independent. Beginning with a runaway victory in Illinois on April 9, Roosevelt won nine of the last ten presidential primaries (including Taft's home state of Ohio), losing only Massachusetts.[14]

Taft also had support from the bulk of the Southern Republican organizations. Delegates from the former Confederate states supported Taft by a 5 to 1 margin. These states had voted solidly Democratic in every presidential election since 1880, and Roosevelt objected that they were given one-quarter of the delegates when they would contribute nothing to a Republican victory.

Convention

The Republican Convention convened in Chicago from June 18 to 22. In the weeks leading up to the convention, many delegates remained uncommitted to a candidate, but by the time the convention formally opened, Taft had won the support of almost every unbound delegate.[15] Roosevelt accused Taft of stealing votes and attempted to have delegates from Arizona, California, Texas, and Washington — all states supporting Taft — removed from the convention, but he was unsuccessful.[16] The delegates chose Taft supporter Elihu Root to serve as chairman of the convention, a move that signaled that Taft was likely to win the nomination.[17]

Roosevelt broke with tradition and attended the convention, where he was welcomed with great support from voters.[18] Despite Roosevelt's presence in Chicago and his attempts to disqualify Taft supporters, the incumbent ticket of Taft and James S. Sherman was renominated on the first ballot.[19] Sherman was the first sitting Vice President re-nominated since John C. Calhoun in 1828. After losing the vote, Roosevelt announced the formation of a new party dedicated "to the service of all the people."[20] This would later come to be known as the Progressive Party. Roosevelt announced that his party would hold its convention in Chicago and that he would accept their nomination if offered.[20] Meanwhile, Taft decided not to campaign before the election beyond his acceptance speech on August 1.[21]

Not since the 1884 election had there been a major schism in the Republican Party, when the Mugwump faction repudiated nominee James G. Blaine and broke with the party. The schism, in which Roosevelt had nearly participated after fighting Blaine's nomination, was a major factor in Blaine's loss to Grover Cleveland.

| Presidential Ballot[22][23][24] | |

| William Howard Taft | 561 |

|---|---|

| Theodore Roosevelt | 107 |

| Robert M. La Follette | 41 |

| Albert B. Cummins | 17 |

| Charles Evans Hughes | 2 |

| Present, not voting | 344 |

| Absent | 6 |

| Vice Presidential Ballot | |

| James S. Sherman | 596 |

|---|---|

| William Borah | 21 |

| Charles Edward Merriam | 20 |

| Herbert S. Hadley | 14 |

| Albert J. Beveridge | 2 |

Democratic Party nomination

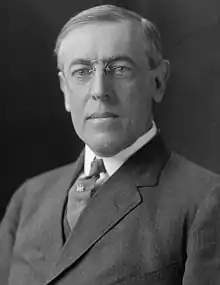

| Woodrow Wilson | Thomas R. Marshall | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

.jpg.webp) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 34th Governor of New Jersey (1911–1913) |

27th Governor of Indiana (1909–1913) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Candidates gallery

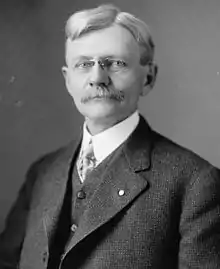

Governor Judson Harmon of Ohio

Governor Judson Harmon of Ohio

Governor Simeon E. Baldwin of Connecticut

Governor Simeon E. Baldwin of Connecticut

The Democratic Convention was held in Baltimore from June 25 to July 2.

Initially, the front-runner was Speaker of the House Champ Clark of Missouri. Though Clark received the most votes on early ballots, he was unable to get the two-thirds majority required to win.

Clark's chances were hurt when Tammany Hall, the powerful New York City Democratic political machine, threw its support behind him. The Tammany endorsement caused William Jennings Bryan, three-time Democratic presidential candidate and leader of the party's progressives, to turn against Clark. Bryan shifted his support to reformist Governor of New Jersey Woodrow Wilson and decried Clark as the candidate of Wall Street. Wilson had consistently finished second in balloting.

Wilson had nearly given up hope and was almost freed his delegates to vote for another candidate. Instead, Bryan's defection from Clark to Wilson led many other delegates to do the same. Wilson gradually gained strength while Clark's support dwindled, and Wilson finally received the nomination on the 46th ballot.

Thomas R. Marshall, the Governor of Indiana who had swung Indiana's votes to Wilson, was named Wilson's running mate.

| (1-22) | Presidential Ballot | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | 6th | 7th | 8th | 9th | 10th | 11th | 12th | 13th | 14th | 15th | 16th | 17th | 18th | 19th | 20th | 21st | 22nd | 23rd | 24th | ||

| Wilson | 324 | 339.75 | 345 | 349.5 | 351 | 354 | 352.5 | 351.5 | 352.5 | 350.5 | 354.5 | 354 | 356 | 361 | 362.5 | 362.5 | 362.5 | 361 | 358 | 388.5 | 395.5 | 396.5 | 399 | 402.5 | |

| Clark | 440.5 | 446.5 | 441 | 443 | 443 | 445 | 449.5 | 448.5 | 452 | 556 | 554 | 547.5 | 554.5 | 553 | 552 | 551 | 545 | 535 | 532 | 512 | 508 | 500.5 | 497.5 | 496 | |

| Harmon | 148 | 141 | 140.5 | 136.5 | 141.5 | 135 | 129.5 | 130 | 127 | 31 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Underwood | 117.5 | 111.25 | 114.5 | 112 | 119.5 | 121 | 123.5 | 123 | 122.5 | 117.5 | 118.5 | 123 | 115.5 | 111 | 110.5 | 112.5 | 112.5 | 125 | 130 | 121.5 | 118.5 | 115 | 114.5 | 115.5 | |

| Foss | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 43 | 45 | 43 | |

| T. Marshall | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | |

| Baldwin | 22 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| W.J. Bryan | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Kern | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4.5 | 3.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| James | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sulzer | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Gaynor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Lewis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Blank | 2 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| (25–46) | Presidential Ballot | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25th | 26th | 27th | 28th | 29th | 30th | 31st | 32nd | 33rd | 34th | 35th | 36th | 37th | 38th | 39th | 40th | 41st | 42nd | 43rd | 44th | 45th | 46th | Unanimous | |

| Wilson | 405 | 407.5 | 406.5 | 437.5 | 436 | 460 | 475.5 | 477.5 | 477.5 | 479.5 | 494.5 | 496.5 | 496.5 | 498.5 | 501.5 | 501.5 | 499.5 | 494 | 602 | 629 | 633 | 990 | 1,088 |

| Clark | 469 | 463.5 | 469 | 468.5 | 468.5 | 455 | 446.5 | 446.5 | 447.5 | 447.5 | 433.5 | 434.5 | 432.5 | 425 | 422 | 423 | 424 | 430 | 329 | 306 | 306 | 84 | |

| Harmon | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 19 | 17 | 14 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 28 | 27 | 27 | 28 | 27 | 25 | 12 | |

| Underwood | 108 | 112.5 | 112 | 112.5 | 112 | 121.5 | 116.5 | 119.5 | 103.5 | 101.5 | 101.5 | 98.5 | 100.5 | 106 | 106 | 106 | 106 | 104 | 98.5 | 99 | 97 | 0 | |

| Foss | 43 | 43 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 30 | 30 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 0 | |

| T. Marshall | 30 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Baldwin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| W.J. Bryan | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Kern | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| James | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sulzer | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Gaynor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Lewis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Blank | 0 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Vice Presidential Ballot | |||

| 1st | 2nd | Unanimous | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thomas R. Marshall | 389 | 644.5 | 1,088 |

| John Burke | 304.67 | 386.33 | |

| George E. Chamberlain | 157 | 12.5 | |

| Elmore W. Hurst | 78 | 0 | |

| James H. Preston | 58 | 0 | |

| Martin J. Wade | 26 | 0 | |

| William F. McCombs | 18 | 0 | |

| John E. Osborne | 8 | 0 | |

| William Sulzer | 3 | 0 | |

| Blank | 46.33 | 44.67 | |

Progressive Party nomination

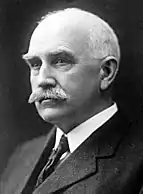

| Theodore Roosevelt | Hiram Johnson | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

.jpg.webp) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 26th President of the United States (1901–1909) |

23rd Governor of California (1911–1917) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Progressives reconvened in Chicago and endorsed the formation of a national Progressive Party. The party was funded by publisher Frank Munsey and businessman George Walbridge Perkins, who served as executive secretary. At their convention on August 5, the new party chose Roosevelt as its presidential nominee and Governor Hiram Johnson from California as his vice presidential running mate.

The Progressives promised to increase federal regulation and protect the welfare of ordinary people. At the convention, Perkins blocked an antitrust plank, shocking reformers who thought of Roosevelt as a true trust-buster. The delegates to the convention sang the hymn "Onward, Christian Soldiers" as their anthem. In his acceptance speech, Roosevelt compared the coming presidential campaign to the Battle of Armageddon and stated that the Progressives were going to "battle for the Lord."

Most progressive politicians remained in the Republican Party.

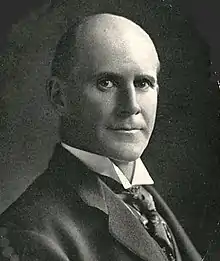

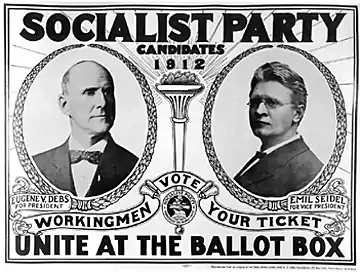

Socialist Party nomination

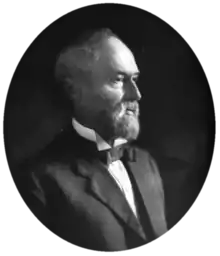

| Eugene V. Debs | Emil Seidel | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Former Indiana State Senator (1885–1889) |

36th Mayor of Milwaukee (1910–1912) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Socialist candidates:

- Eugene V. Debs, former State Senator from Indiana

- Emil Seidel, Mayor of Milwaukee, Wisconsin

- Charles Edward Russell, journalist from Iowa

The Socialist Party of America was a highly factionalized coalition of local parties based in industrial cities and rooted in ethnic, especially German and Finnish, communities. It had some support in formerly Populist rural and mining areas in the West, especially Oklahoma. By 1912, the party claimed more than a thousand locally elected officials in 33 states and 160 cities, especially the Midwest. Eugene V. Debs had run for president in 1900, 1904, and 1908, primarily to encourage the local effort, and he did so again in 1912 with little challenge to his nomination.[25]

The party was divided into two main factions. The conservative faction led by Congressman Victor L. Berger of Milwaukee promoted pragmatic democratic reform, fought corruption, and opposed immigration as both a wage suppressant and drain on public resources. The radical faction sought to overthrow capitalism, tried to infiltrate labor unions, and sought to cooperate with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW or "Wobblies"). It supported immigration to increase ranks for the war on capitalism. With few exceptions, the party had weak or nonexistent links to local labor unions.

Many of these issues had been debated at the First National Congress of the Socialist Party in 1910 and again at the 1912 national convention in Indianapolis. At the convention, the radicals won an early test by seating IWW leader Bill Haywood on the Executive Committee and passed a resolution favoring industrial unionism. Conservatives responded by amending the party constitution to expel any who favored industrial sabotage or syndicalism (both positions of the IWW) and who refused to participate in American elections. The convention adopted a conservative platform calling for the cooperative organization of prisons, a national bureau of health, and the abolition of the Senate and the presidential veto.

Debs did not attend. He saw his mission as keeping the disparate units together in the hope that someday a common goal would be found.

| Presidential Ballot | |

| Eugene V. Debs | 165 |

|---|---|

| Emil Seidel | 56 |

| Charles Edward Russell | 54 |

| Vice Presidential Ballot | |

| Emil Seidel | 159 |

|---|---|

| Dan Hogan | 73 |

| John W. Slayton | 24 |

General election

The 1912 presidential campaign was bitterly contested.

Roosevelt conducted a vigorous national campaign for the Progressive Party, denouncing the way the Republican nomination had been "stolen". He bundled together his reforms under the rubric of "The New Nationalism" and stumped the country for a strong federal role in regulating the economy and chastising bad corporations. Roosevelt rallied progressives with speeches denouncing the political establishment. He promised "an expert tariff commission, wholly removed from the possibility of political pressure or of improper business influence."[26]

Wilson supported a policy called "The New Freedom". This policy was based mostly on individualism instead of a strong government.

Though Wilson's rhetoric paid homage to the traditional skepticism of government and "collectivism" in the Democratic Party, after his election he would embrace some of the progressive reforms which Roosevelt campaigned on.

Taft campaigned quietly and spoke of the need for judges to be more powerful than elected officials. The departure of the progressives left the Republican Party firmly controlled by the conservative wing. Much of the Republican effort was designed to discredit Roosevelt as a dangerous radical, but this had little effect. Many of the nation's pro-Republican newspapers depicted Roosevelt as an egotist running only to spoil Taft's chances and feed his vanity.

The Socialists had little funding. Debs' campaign spent only $66,000, mostly on 3.5 million leaflets and travel to locally organized rallies. His biggest event was a speech to 15,000 supporters in New York City. The crowd sang "La Marseillaise" and "The Internationale." Debs's running mate Emil Seidel boasted:

"Only a year ago workingmen were throwing decayed vegetables and rotten eggs at us but now all is changed... Eggs are too high. There is a great giant growing up in this country that will someday take over the affairs of this nation. He is a little giant now but he is growing fast. The name of this little giant is socialism."

Debs insisted that Democrats, Progressives, and Republicans alike were financed by the trusts and that only the Socialists represented labor. He condemned "Injunction Bill Taft" and ridiculed Roosevelt as "a charlatan, mountebank, and fraud, and his Progressive promises and pledges as the mouthings of a low and utterly unprincipled self-seeker and demagogue."

Attempted assassination of Theodore Roosevelt

At a campaign stop in Milwaukee on October 14, John Flammang Schrank, a saloonkeeper from New York, shot Roosevelt in the chest. The bullet penetrated his steel eyeglass case and a 50-page single-folded copy of his speech Progressive Cause Greater Than Any Individual and became lodged in his chest. Schrank was immediately disarmed and captured.[27] Schrank had been stalking Roosevelt. He was demented and said the ghost of President McKinley ordered him to kill Roosevelt to prevent a third term.[28]

Roosevelt shouted for Schrank to remain unharmed and assured the crowd he was all right, then ordered police to take charge of Schrank and ensure no violence was done to him.[29] Roosevelt, an experienced hunter and anatomist, correctly concluded that since he was not coughing blood, the bullet had not reached his lung. He declined suggestions to go to the hospital and instead delivered his scheduled speech with blood seeping into his shirt.[30] His opening comments to the gathered crowd were, "Ladies and gentlemen, I don't know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot, but it takes more than that to kill a bull moose." He spoke for 90 minutes before completing his speech and accepting medical attention.[31][32]

Afterward, probes and an x-ray showed that the bullet had lodged in Roosevelt's chest muscle, but did not penetrate the pleura. Doctors concluded that it would be less dangerous to leave it in place than to attempt to remove it, and Roosevelt carried the bullet with him for the rest of his life.[33][34]

Taft was not campaigning and focused on his presidential duties. Wilson briefly suspended his campaigning. By October 17, Wilson was back on the campaign trail but avoided any criticism of Roosevelt or his party.[35] He spent two weeks recuperating before returning to the campaign trail with a major speech on October 30, designed to reassure his supporters he was strong enough for the presidency.[36]

Death of Vice President Sherman

Vice President James S. Sherman died on October 30, less than one week before the election, leaving Taft without a running mate. By this point it was widely accepted that Taft was certain to lose re-election, and so the party did not bother formally selecting a replacement for Sherman. Nicholas M. Butler was eventually designated to receive electoral votes that would have been cast for Sherman.

Results

On November 5, Wilson captured the presidency handily by carrying a record 40 states.

As of 2021, this is the only presidential election since 1860 in which either 4 candidates received more than 5% of the popular vote or a third-party candidate outperformed a Republican or Democrat in the general election. Wilson won the presidency with a lower percentage of the popular vote than any candidate since Abraham Lincoln in 1860. Taft's result remains the worst performance for any incumbent president, both in terms of electoral votes (8) and share of popular votes (23.17%). His 8 electoral votes remain the fewest by a Republican or Democrat, matched by Alf Landon's 1936 campaign.

Electoral results

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote | Electoral vote |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Electoral vote | ||||

| Thomas Woodrow Wilson | Democratic | New Jersey | 6,296,284 | 41.84% | 435 | Thomas Riley Marshall | Indiana | 435 |

| Theodore Roosevelt Jr. | Progressive | New York | 4,122,721 | 27.40% | 88 | Hiram Warren Johnson | California | 88 |

| William Howard Taft (Incumbent) | Republican | Ohio | 3,486,242 | 23.17% | 8 | Nicholas Murray Butler | New York | 8 |

| Eugene Victor Debs | Socialist | Indiana | 901,551 | 5.99% | 0 | Emil Seidel | Wisconsin | 0 |

| Eugene Wilder Chafin | Prohibition | Arizona | 208,156 | 1.38% | 0 | Aaron Sherman Watkins | Ohio | 0 |

| Arthur Elmer Reimer | Socialist Labor | Massachusetts | 29,324 | 0.19% | 0 | August Gillhaus | New York | 0 |

| Other | 4,556 | 0.03% | — | Other | — | |||

| Total | 15,048,834 | 100% | 531 | 531 | ||||

| Needed to win | 266 | 266 | ||||||

Source (Popular Vote): Leip, David. "1912 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 28, 2005.

Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 31, 2005.

Statistical analysis

Wilson's raw vote total was less than William Jennings Bryan totaled in any of his three campaigns.[37] In only two regions, New England and the Pacific, was Wilson's vote greater than the greatest Bryan vote.[38]

Results by state

The 1912 election was the first to include all 48 of the current contiguous United States.

Few states were carried by any candidate with a majority of the popular vote. Wilson won a majority in the eleven former Confederate states. Only South Dakota, where Taft did not appear on the ballot, gave Roosevelt a majority. Taft won only two states, Vermont and Utah, each with a plurality.[37]

This was the first time since 1852 that Iowa, Maine, New Hampshire, Ohio, and Rhode Island voted for a Democrat, and the first time in history that Massachusetts voted Democratic.

Democrats would not win Maine again until 1964, Connecticut and Delaware until 1936, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, West Virginia, and Wisconsin until 1932, and Massachusetts and Rhode Island until 1928.

| States/districts won by Wilson/Marshall |

| States/districts won by Roosevelt/Johnson |

| States/districts won by Taft/Butler |

| Woodrow Wilson Democratic |

Theodore Roosevelt Progressive |

William H. Taft Republican |

Eugene V. Debs Socialist |

Eugene Chafin Prohibition |

Arthur Reimer Socialist Labor |

Margin | State Total | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | # | |

| Alabama | 12 | 82,438 | 69.89 | 12 | 22,680 | 19.23 | - | 9,807 | 8.31 | - | 3,029 | 2.57 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 59,758 | 50.66 | 117,959 | AL |

| Arizona | 3 | 10,324 | 43.52 | 3 | 6,949 | 29.29 | - | 3,021 | 12.74 | - | 3,163 | 13.33 | - | 265 | 1.12 | - | - | - | - | 3,375 | 14.23 | 23,722 | AZ |

| Arkansas | 9 | 68,814 | 55.01 | 9 | 21,644 | 17.30 | - | 25,585 | 20.45 | - | 8,153 | 6.52 | - | 908 | 0.73 | - | - | - | - | 43,229 | 34.55 | 125,104 | AR |

| California | 13 | 283,436 | 41.81 | 2 | 283,610 | 41.83 | 11 | 3,914 | 0.58 | - | 79,201 | 11.68 | - | 23,366 | 3.45 | - | - | - | - | -174 | -0.03 | 673,527 | CA |

| Colorado | 6 | 114,232 | 42.80 | 6 | 72,306 | 27.09 | - | 58,386 | 21.88 | - | 16,418 | 6.15 | - | 5,063 | 1.90 | - | 475 | 0.18 | - | 41,926 | 15.71 | 266,880 | CO |

| Connecticut | 7 | 74,561 | 39.16 | 7 | 34,129 | 17.92 | - | 68,324 | 35.88 | - | 10,056 | 5.28 | - | 2,068 | 1.09 | - | 1,260 | 0.66 | - | 6,237 | 3.28 | 190,398 | CT |

| Delaware | 3 | 22,631 | 46.48 | 3 | 8,886 | 18.25 | - | 15,998 | 32.85 | - | 556 | 1.14 | - | 623 | 1.28 | - | - | - | - | 6,633 | 13.62 | 48,694 | DE |

| Florida | 6 | 35,343 | 69.52 | 6 | 4,555 | 8.96 | - | 4,279 | 8.42 | - | 4,806 | 9.45 | - | 1,854 | 3.65 | - | - | - | - | 30,537 | 60.07 | 50,837 | FL |

| Georgia | 14 | 93,087 | 76.63 | 14 | 21,985 | 18.10 | - | 5,191 | 4.27 | - | 1,058 | 0.87 | - | 149 | 0.12 | - | - | - | - | 71,102 | 58.53 | 121,470 | GA |

| Idaho | 4 | 33,921 | 32.08 | 4 | 25,527 | 24.14 | - | 32,810 | 31.02 | - | 11,960 | 11.31 | - | 1,536 | 1.45 | - | - | - | - | 1,111 | 1.05 | 105,754 | ID |

| Illinois | 29 | 405,048 | 35.34 | 29 | 386,478 | 33.72 | - | 253,593 | 22.13 | - | 81,278 | 7.09 | - | 15,710 | 1.37 | - | 4,066 | 0.35 | - | 18,570 | 1.62 | 1,146,173 | IL |

| Indiana | 15 | 281,890 | 43.07 | 15 | 162,007 | 24.75 | - | 151,267 | 23.11 | - | 36,931 | 5.64 | - | 19,249 | 2.94 | - | 3,130 | 0.48 | - | 119,883 | 18.32 | 654,474 | IN |

| Iowa | 13 | 185,325 | 37.64 | 13 | 161,819 | 32.87 | - | 119,805 | 24.33 | - | 16,967 | 3.45 | - | 8,440 | 1.71 | - | - | - | - | 23,506 | 4.77 | 492,356 | IA |

| Kansas | 10 | 143,663 | 39.30 | 10 | 120,210 | 32.88 | - | 74,845 | 20.47 | - | 26,779 | 7.33 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 23,453 | 6.42 | 365,497 | KS |

| Kentucky | 13 | 219,484 | 48.48 | 13 | 101,766 | 22.48 | - | 115,510 | 25.52 | - | 11,646 | 2.57 | - | 3,253 | 0.72 | - | 1,055 | 0.23 | - | 103,974 | 22.97 | 452,714 | KY |

| Louisiana | 10 | 60,871 | 76.81 | 10 | 9,283 | 11.71 | - | 3,833 | 4.84 | - | 5,261 | 6.64 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 51,588 | 65.10 | 79,248 | LA |

| Maine | 6 | 51,113 | 39.43 | 6 | 48,495 | 37.41 | - | 26,545 | 20.48 | - | 2,541 | 1.96 | - | 946 | 0.73 | - | - | - | - | 2,618 | 2.02 | 129,640 | ME |

| Maryland | 8 | 112,674 | 48.57 | 8 | 57,789 | 24.91 | - | 54,956 | 23.69 | - | 3,996 | 1.72 | - | 2,244 | 0.97 | - | 322 | 0.14 | - | 54,885 | 23.66 | 231,981 | MD |

| Massachusetts | 18 | 173,408 | 35.53 | 18 | 142,228 | 29.14 | - | 155,948 | 31.95 | - | 12,616 | 2.58 | - | 2,754 | 0.56 | - | 1,102 | 0.23 | - | 17,460 | 3.58 | 488,056 | MA |

| Michigan | 15 | 150,751 | 27.36 | - | 214,584 | 38.95 | 15 | 152,244 | 27.63 | - | 23,211 | 4.21 | - | 8,934 | 1.62 | - | 1,252 | 0.23 | - | -62,340 | -11.31 | 550,976 | MI |

| Minnesota | 12 | 106,426 | 31.84 | - | 125,856 | 37.66 | 12 | 64,334 | 19.25 | - | 27,505 | 8.23 | - | 7,886 | 2.36 | - | 2,212 | 0.66 | - | -19,430 | -5.81 | 334,219 | MN |

| Mississippi | 10 | 57,324 | 88.90 | 10 | 3,549 | 5.50 | - | 1,560 | 2.42 | - | 2,050 | 3.18 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 53,775 | 83.39 | 64,483 | MS |

| Missouri | 18 | 330,746 | 47.35 | 18 | 124,375 | 17.80 | - | 207,821 | 29.75 | - | 28,466 | 4.07 | - | 5,380 | 0.77 | - | 1,778 | 0.25 | - | 122,925 | 17.60 | 698,566 | MO |

| Montana | 4 | 27,941 | 35.00 | 4 | 22,456 | 28.13 | - | 18,512 | 23.19 | - | 10,885 | 13.64 | - | 32 | 0.04 | - | - | - | - | 5,485 | 6.87 | 79,826 | MT |

| Nebraska | 8 | 109,008 | 43.69 | 8 | 72,681 | 29.13 | - | 54,226 | 21.74 | - | 10,185 | 4.08 | - | 3,383 | 1.36 | - | - | - | - | 36,327 | 14.56 | 249,483 | NE |

| Nevada | 3 | 7,986 | 39.70 | 3 | 5,620 | 27.94 | - | 3,196 | 15.89 | - | 3,313 | 16.47 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2,366 | 11.76 | 20,115 | NV |

| New Hampshire | 4 | 34,724 | 39.48 | 4 | 17,794 | 20.23 | - | 32,927 | 37.43 | - | 1,981 | 2.25 | - | 535 | 0.61 | - | - | - | - | 1,797 | 2.04 | 87,961 | NH |

| New Jersey | 14 | 178,289 | 41.20 | 14 | 145,410 | 33.60 | - | 88,835 | 20.53 | - | 15,948 | 3.69 | - | 2,936 | 0.68 | - | 1,321 | 0.31 | - | 32,879 | 7.60 | 432,739 | NJ |

| New Mexico | 3 | 20,437 | 41.39 | 3 | 8,347 | 16.90 | - | 17,733 | 35.91 | - | 2,859 | 5.79 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2,704 | 5.48 | 49,376 | NM |

| New York | 45 | 655,573 | 41.27 | 45 | 390,093 | 24.56 | - | 455,487 | 28.68 | - | 63,434 | 3.99 | - | 19,455 | 1.22 | - | 4,273 | 0.27 | - | 200,086 | 12.60 | 1,588,315 | NY |

| North Carolina | 12 | 144,407 | 59.24 | 12 | 69,135 | 28.36 | - | 29,129 | 11.95 | - | 987 | 0.40 | - | 118 | 0.05 | - | - | - | - | 75,272 | 30.88 | 243,776 | NC |

| North Dakota | 5 | 29,555 | 34.14 | 5 | 25,726 | 29.71 | - | 23,090 | 26.67 | - | 6,966 | 8.05 | - | 1,243 | 1.44 | - | - | - | - | 3,829 | 4.42 | 86,580 | ND |

| Ohio | 24 | 424,834 | 40.96 | 24 | 229,807 | 22.16 | - | 278,168 | 26.82 | - | 90,144 | 8.69 | - | 11,511 | 1.11 | - | 2,630 | 0.25 | - | 146,666 | 14.14 | 1,037,094 | OH |

| Oklahoma | 10 | 119,156 | 46.95 | 10 | - | - | - | 90,786 | 35.77 | - | 41,674 | 16.42 | - | 2,185 | 0.86 | - | - | - | - | 28,370 | 11.18 | 253,801 | OK |

| Oregon | 5 | 47,064 | 34.34 | 5 | 37,600 | 27.44 | - | 34,673 | 25.30 | - | 13,343 | 9.74 | - | 4,360 | 3.18 | - | - | - | - | 9,464 | 6.91 | 137,040 | OR |

| Pennsylvania | 38 | 395,637 | 32.49 | - | 444,894 | 36.53 | 38 | 273,360 | 22.45 | - | 83,614 | 6.87 | - | 19,525 | 1.60 | - | 706 | 0.06 | - | -49,257 | -4.04 | 1,217,736 | PA |

| Rhode Island | 5 | 30,412 | 39.04 | 5 | 16,878 | 21.67 | - | 27,703 | 35.56 | - | 2,049 | 2.63 | - | 616 | 0.79 | - | 236 | 0.30 | - | 2,709 | 3.48 | 77,894 | RI |

| South Carolina | 9 | 48,357 | 95.94 | 9 | 1,293 | 2.57 | - | 536 | 1.06 | - | 164 | 0.33 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 47,064 | 93.37 | 50,350 | SC |

| South Dakota | 5 | 48,942 | 42.07 | - | 58,811 | 50.56 | 5 | - | - | - | 4,662 | 4.01 | - | 3,910 | 3.36 | - | - | - | - | -9,869 | -8.48 | 116,325 | SD |

| Tennessee | 12 | 133,021 | 52.80 | 12 | 54,041 | 21.45 | - | 60,475 | 24.00 | - | 3,564 | 1.41 | - | 832 | 0.33 | - | - | - | - | 72,546 | 28.80 | 251,933 | TN |

| Texas | 20 | 221,589 | 72.62 | 20 | 28,853 | 9.46 | - | 26,755 | 8.77 | - | 25,743 | 8.44 | - | 1,738 | 0.57 | - | 442 | 0.14 | - | 192,736 | 63.17 | 305,120 | TX |

| Utah | 4 | 36,579 | 32.55 | - | 24,174 | 21.51 | - | 42,100 | 37.46 | 4 | 9,023 | 8.03 | - | - | - | - | 510 | 0.45 | - | -5,521 | -4.91 | 112,386 | UT |

| Vermont | 4 | 15,354 | 24.43 | - | 22,132 | 35.22 | - | 23,332 | 37.13 | 4 | 928 | 1.48 | - | 1,095 | 1.74 | - | - | - | - | -1,200 | -1.91 | 62,841 | VT |

| Virginia | 12 | 90,332 | 65.95 | 12 | 21,776 | 15.90 | - | 23,288 | 17.00 | - | 820 | 0.60 | - | 709 | 0.52 | - | 50 | 0.04 | - | 67,044 | 48.95 | 136,975 | VA |

| Washington | 7 | 86,840 | 26.90 | - | 113,698 | 35.22 | 7 | 70,445 | 21.82 | - | 40,134 | 12.43 | - | 9,810 | 3.04 | - | 1,872 | 0.58 | - | -26,858 | -8.32 | 322,799 | WA |

| West Virginia | 8 | 113,197 | 42.11 | 8 | 79,112 | 29.43 | - | 56,754 | 21.11 | - | 15,248 | 5.67 | - | 4,517 | 1.68 | - | - | - | - | 34,085 | 12.68 | 268,828 | WV |

| Wisconsin | 13 | 164,230 | 41.06 | 13 | 62,448 | 15.61 | - | 130,596 | 32.65 | - | 33,476 | 8.37 | - | 8,584 | 2.15 | - | 632 | 0.16 | - | 33,634 | 8.41 | 399,966 | WI |

| Wyoming | 3 | 15,310 | 36.20 | 3 | 9,232 | 21.83 | - | 14,560 | 34.42 | - | 2,760 | 6.53 | - | 434 | 1.03 | - | - | - | - | 750 | 1.77 | 42,296 | WY |

| TOTALS: | 531 | 6,296,284 | 41.84 | 435 | 4,122,721 | 27.40 | 88 | 3,486,242 | 23.17 | 8 | 901,551 | 5.99 | - | 208,156 | 1.38 | - | 29,324 | 0.19 | - | 2,173,563 | 14.44 | 15,044,278 | US |

Close states

Margin of victory less than 1% (13 electoral votes):

- California, 0.03%

Margin of victory less than 5% (142 electoral votes):

- Idaho, 1.05%

- Illinois, 1.62%

- Wyoming, 1.77%

- Vermont, 1.91%

- Maine, 2.02%

- New Hampshire, 2.04%

- Connecticut, 3.28%

- Rhode Island, 3.48%

- Massachusetts, 3.58%

- Pennsylvania, 4.04%

- North Dakota, 4.42%

- Iowa, 4.77%

- Utah, 4.91%

Margin of victory between 5% and 10% (73 electoral votes):

- New Mexico, 5.48%

- Minnesota, 5.81%

- Kansas, 6.42%

- Montana, 6.87%

- Oregon, 6.91%

- New Jersey, 7.60%

- Washington, 8.32%

- Wisconsin, 8.41%

- South Dakota, 8.48%

Tipping point state:

- New York, 12.6% (for a Wilson victory)

- Ohio, 18.9% (for a Roosevelt victory)

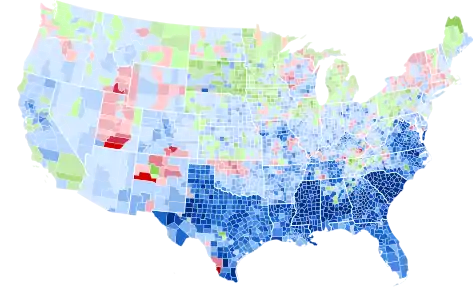

By county

In a plurality of 1,396 counties, no candidate obtained a majority.[39]

Wilson won 1,969 counties but held a majority in only 1,237, less than Bryan had had in any of his campaigns.[38]

"Other(s)", mostly Roosevelt, won a plurality in 772 counties and a majority in 305 counties. Most of them in Pennsylvania (48), Illinois (33), Michigan (68), Minnesota (75), Iowa (49), South Dakota (54), Nebraska (32), Kansas (51), Washington (38), and California (44).

Debs carried four counties: Lake and Beltrami in Minnesota, Burke in North Dakota, and Crawford in Kansas. These are the only counties ever to vote for the Socialist presidential nominee.

Taft won a plurality in only 232 counties and a majority in only 35. In addition to South Dakota and California, where there was no Taft ticket, Taft carried no counties in Maine, New Jersey, Minnesota, Nevada, Arizona, and seven "Solid South" states.[38]

Nine counties did not record any votes due to either black disenfranchisement or being inhabited only by Native Americans, who would not gain full citizenship for twelve more years.

As of 2021, 1912 remains the last election in which the key Indiana counties of Hamilton and Hendricks, along with Walworth County, Wisconsin, Pulaski and Laurel Counties in Kentucky and Hawkins County, Tennessee have given a plurality to the Democratic candidate.[40]

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Democratic)

- Greenville County, South Carolina 100.00%

- Marlboro County, South Carolina 100.00%

- Hampton County, South Carolina 100.00%

- Jasper County, South Carolina 100.00%

- Reagan County, Texas 100.00%

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Progressive)

- Scott County, Tennessee 75.15%

- Campbell County, South Dakota 74.93%

- Avery County, North Carolina 72.69%

- Hutchinson County, South Dakota 67.84%

- Hamlin County, South Dakota 66.79%

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Republican)

- Zapata County, Texas 80.89%

- Valencia County, New Mexico 77.25%

- Kane County, Utah 75.40%

- Clinton County, Kentucky 64.79%

- Huerfano County, Colorado 63.36%

Maps

Results by state

Results by state Results by county, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote

Results by county, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote Results by county, shaded according to percentage of the vote for Wilson

Results by county, shaded according to percentage of the vote for Wilson Results by county, shaded according to percentage of the vote for Taft

Results by county, shaded according to percentage of the vote for Taft Results by county, shaded according to percentage of the vote for all others

Results by county, shaded according to percentage of the vote for all others A continuous cartogram of the 1912 United States presidential election

A continuous cartogram of the 1912 United States presidential election Cartogram shaded according to percentage of the vote for Wilson

Cartogram shaded according to percentage of the vote for Wilson Cartogram shaded according to percentage of the vote for Taft

Cartogram shaded according to percentage of the vote for Taft Cartogram shaded according to percentage of the vote for all others

Cartogram shaded according to percentage of the vote for all others

By city

| City | ST | Wilson | Taft | Roosevelt | Debs | Others | Totals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| San Francisco | CA | 48,953 | 65 | 38,610 | 12,354 | 1,166 | 101,148 |

| Denver | CO | 26,690 | 8,155 | 25,154 | 2,750 | 764 | 63,513 |

| Bridgeport | CT | 5,870 | 4,625 | 3,654 | 1,511 | 284 | 15,944 |

| Hartford | CT | 7,481 | 6,396 | 2,467 | 849 | 258 | 17,451 |

| New Haven | CT | 8,946 | 7,291 | 3,252 | 1,696 | 442 | 21,627 |

| Waterbury | CT | 4,440 | 3,261 | 1,675 | 787 | 212 | 10,375 |

| Des Moines | IA | 6,005 | 3,669 | 6,432 | |||

| Chicago | IL | 124,297 | 71,030 | 150,290 | 53,743 | 2,806 | 402,166 |

| Ft. Wayne | IN | 4,892 | 1,896 | 2,793 | |||

| Indianapolis | IN | 18,306 | 8,722 | 9,693 | |||

| New Orleans | LA | 26,433 | 904 | 5,692 | |||

| Boston | MA | 43,065 | 21,427 | 21,533 | 1,818 | 428 | 88,271 |

| Cambridge | MA | 6,667 | 3,362 | 3,403 | 192 | 68 | 13,692 |

| Fall River | MA | 5,160 | 4,224 | 3,453 | 219 | 256 | 13,312 |

| Lowell | MA | 5,459 | 3,034 | 3,783 | 170 | 82 | 12,528 |

| Lynn | MA | 4,595 | 4,144 | 4,764 | 583 | 178 | 14,264 |

| New Bedford | MA | 3,290 | 4,177 | 1,905 | 626 | 98 | 10,096 |

| Somerville | MA | 4,062 | 3,757 | 4,072 | 176 | 78 | 12,145 |

| Springfield | MA | 4,375 | 5,167 | 3,161 | 555 | 58 | 13,316 |

| Worcester | MA | 6,049 | 10,532 | 4,818 | 230 | 140 | 21,769 |

| Baltimore | MD | 48,030 | 15,597 | 33,679 | 1,763 | 253 | 99,322 |

| Kansas City | MO | 26,954 | 4,646 | 20,894 | 1,470 | 465 | 54,429 |

| St. Louis | MO | 58,845 | 46,509 | 24,746 | 9,159 | 1,068 | 140,327 |

| Bayonne | NJ | 3,717 | 1,184 | 2,552 | |||

| Camden | NJ | 6,895 | 5,517 | 4,707 | |||

| Elizabeth | NJ | 5,139 | 1,900 | 3,953 | |||

| Jersey City | NJ | 21,069 | 4,070 | 11,986 | |||

| Newark | NJ | 14,031 | 10,780 | 19,721 | |||

| Paterson | NJ | 7,437 | 3,007 | 7,223 | |||

| Trenton | NJ | 5,146 | 3,898 | 4,753 | |||

| Buffalo | NY | 26,192 | 14,433 | 20,769 | |||

| New York City | NY | 312,426 | 126,582 | 188,896 | 33,239 | 2,730 | 663,873 |

| Rochester | NY | 13,430 | 12,230 | 11,102 | 2,593 | 636 | 39,991 |

| Cincinnati | OH | 31,221 | 30,588 | 9,970 | 6,520 | 401 | 78,700 |

| Allentown | PA | 4,627 | 1,224 | 3,475 | 686 | 59 | 10,071 |

| Erie | PA | 3,407 | 2,378 | 1,898 | 1,464 | 140 | 9,287 |

| Philadelphia | PA | 66,308 | 91,944 | 82,963 | 9,784 | 691 | 251,690 |

| Pittsburgh | PA | 17,352 | 14,658 | 25,394 | 8,498 | 534 | 66,436 |

| Reading | PA | 6,130 | 1,657 | 6,719 | 2,800 | 83 | 17,389 |

| Scranton | PA | 6,193 | 1,817 | 7,971 | 564 | 214 | 16,759 |

| Wilkes-Barre | PA | 2,905 | 1,178 | 3,951 | 219 | 47 | 8,300 |

| Salt Lake City | UT | 7,488 | 8,964 | 6,587 | 2,498 | ||

| Norfolk | VA | 3,539 | 195 | 451 | 33 | 10 | 4,228 |

| Richmond | VA | 5,636 | 405 | 483 | 91 | 12 | 6,627 |

| Milwaukee | WI | 24,501 | 15,092 | 5,127 | 17,708 | 511 | 62,939 |

See also

Notes

- Incumbent vice-president James S. Sherman was re-nominated to serve as Taft's running-mate, but died six days prior to the election. Butler was chosen to receive the Republican vice-presidential votes after the election.

- Though he had become President upon the William McKinley assassination in 1901, only six months of McKinley's term had elapsed. Thus, Roosevelt had served nearly a full eight years, effectively two full terms. Although the Twenty-Second Amendment to the Constitution did not become effective until 1951, it would have barred Roosevelt from seeking another term, since he had served more than two years to which some other person (McKinley) and been elected.

References

- "Voter Turnout in Presidential Elections". The American Presidency Project. UC Santa Barbara.

- Morris, Edmund. Colonel Roosevelt. New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks. pp. 215, 646.

- Morris, Edmund. Colonel Roosevelt. New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks. pp. 215, 646.

- Coletta, Presidency of William Howard Taft ch 3

- G. M. Fisk, "The Payne-Aldrich Tariff" Political Science Quarterly, (1910). 25(1), 35-39. doi:10.2307/2141008

- Stanley D. Solvick, "William Howard Taft and the Payne-Aldrich Tariff." Mississippi Valley Historical Review 50.3 (1963): 424-442 online.

- Anderson (1973), p.79

- Schweikart and Allen, p. 491.

- O'Mara, Margaret. Pivotal Tuesdays. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 32.

- Schantz, Harvey L. American Presidential Elections. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 169.

- Campbell, James E. The Presidential Pulse of Congressional Elections. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. p. 261.

- Roosevelt, Theodore (January 24, 1911). "Letter from Theodore Roosevelt to William Allen White". Letter to William Allen White. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- O'Mara, Margaret. Pivotal Tuesdays. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 35–37.

- "History, Travel, Arts, Science, People, Places | Smithsonian". Smithsonianmag.com. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- O'Mara, Margaret. Pivotal Tuesdays. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 43–44.

- "Roosevelt, Beaten, to Bolt Today; Gives the Word in Early Morning; Taft's Nomination Seems Assured". New York Times. June 20, 1912. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- "Taft Victory in the First Clash; Root Chosen Chairman, 558 to 502". New York Times. June 19, 1912. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- O'Mara, Margaret. Pivotal Tuesdays. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 44.

- "Taft Nominee; Sherman His Running Mate". Chicago Tribune. June 23, 1912. Retrieved October 12, 2020.(subscription required)

- O'Laughlin, John (June 23, 1912). "Roosevelt Is Named Leader Of New Party". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved October 12, 2020.(subscription required)

- Henry F. Pringle, The Life and Times of William Howard Taft (1939) 2:818, 832, 834,

- "Taft Is Nominated On First Ballot". Santa Cruz News. Santa Cruz, CA. June 22, 1912. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- "Taft Wins With 561". The Courier. Harrisburg, PA. June 23, 1912. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- Pietrusza, David (2007). 1920: The Year of the Six Presidents. New York: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 978-0-7867-1622-7.

- Ira Kipnis, The American Socialist Movement, 1897–1912 1952.

- Theodore Roosevelt Association. "The New Nationalism." The New Nationalism - Theodore Roosevelt Association. N.p., n.d. Web. 17 Apr. 2017.

- Gerard Helferich, Theodore Roosevelt and the Assassin: Madness, Vengeance, and the Campaign of 1912 (2013)

- Lewis Gould, Four Hats in the Ring: The 1912 Election and the Birth of Modern American Politics (2008) p 171.

- Remey, Oliver E.; Cochems, Henry F.; Bloodgood, Wheeler P. (1912). The Attempted Assassination of Ex-President Theodore Roosevelt. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: The Progressive Publishing Company. p. 192.

- "Medical History of American Presidents". Doctor Zebra. Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- "Excerpt", Detroit Free Press, History buff, archived from the original on April 19, 2015, retrieved January 23, 2018.

- "It Takes More Than That to Kill a Bull Moose: The Leader and The Cause". Theodore Roosevelt Association. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- "Roosevelt Timeline". Theodore Roosevelt. Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- Timeline of Theodore Roosevelt's Life by the Theodore Roosevelt Association at http://www.theodoreroosevelt.org

- "WILSON STARTS ON A TOUR.: Will Not Touch on Third Party's Programme in Speeches." New York Times Oct 17. 1912, p. 10.

- Morris, Edmund. Colonel Roosevelt. New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks. pp. 250–251.

- The Presidential Vote, 1896–1932, Edgar E. Robinson, pg. 14

- The Presidential Vote, 1896–1932, Edgar E. Robinson, pg. 15

- The Presidential Vote, 1896–1932, Edgar E. Robinson, pg. 17

- Sullivan, Robert David; ‘How the Red and Blue Map Evolved Over the Past Century’; America Magazine in The National Catholic Review; June 29, 2016

Further reading

- Anders, O. Fritiof. "The Swedish-American Press in the Election of 1912" Swedish Pioneer Historical Quarterly (1963) 14#3 pp 103–126

- Broderick, Francis L. Progressivism at risk: Electing a president in 1912 (Praeger, 1989).

- Chace, James (2004). 1912: Wilson, Roosevelt, Taft, and Debs—The Election That Changed the Country. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0394-1.

- Cooper, John Milton, Jr. (1983). The Warrior and the Priest: Woodrow Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt. Cambridge: Belknap Press. ISBN 0-674-94751-7.

- Cowan, Geoffrey. Let the People Rule: Theodore Roosevelt and the Birth of the Presidential Primary (2016).

- Delahaye, Claire. "The New Nationalism and Progressive Issues: The Break with Taft and the 1912 Campaign," in Serge Ricard, ed., A Companion to Theodore Roosevelt (2011) pp 452–67. online

- DeWitt, Benjamin P. The Progressive Movement: A Non-Partisan, Comprehensive Discussion of Current Tendencies in American Politics. (1915).

- Flehinger, Brett. The 1912 Election and the Power of Progressivism: A Brief History with Documents (Bedford/St. Martin's, 2003).

- Gable, John A. The Bullmoose Years: Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive Party. (Kennikat Press, 1978).

- Gould, Lewis L. Four hats in the ring: The 1912 election and the birth of modern American politics (UP of Kansas, 2008).

- Hahn, Harlan. "The Republican Party Convention of 1912 and the Role of Herbert S. Hadley in National Politics." Missouri Historical Review 59.4 (1965): 407-423. Taft was willing to compromise with Missouri Governor Herbert S. Hadley as presidential nominee; TR said no.

- Jensen, Richard. "Theodore Roosevelt" in Encyclopedia of Third Parties. (ME Sharpe, 2000). pp 702–707.

- Kipnis, Ira (1952). The American Socialist Movement, 1897–1912. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Kraig, Robert Alexander. "The 1912 Election and the Rhetorical Foundations of the Liberal State." Rhetoric and Public Affairs (2000): 363–395. in JSTOR

- Link, Arthur S. (1956). Wilson: Volume 1, The Road to the White House.

- Milkis, Sidney M., and Daniel J. Tichenor. "'Direct Democracy' and Social Justice: The Progressive Party Campaign of 1912." Studies in American Political Development 8#2 (1994): 282-340. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0898588X00001267

- Milkis, Sidney M. Theodore Roosevelt, the Progressive Party, and the Transformation of American Democracy. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2009.

- Morgan, H. Wayne (1962). Eugene V. Debs: Socialist for President. Syracuse University Press.

- Mowry, George E. (1946). Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive Movement. Madison: Wisconsin University Press. online

- Mowry, George E. "The Election of 1912" in Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., and Fred L Israel, eds., History of American Presidential Elections: 1789-1968 (1971) 3: 2135-2427. online

- Mowry, George E. The Era of Theodore Roosevelt and the Birth of Modern America. (Harper and Row, 1962) online.

- O'Mara, Margaret. Pivotal Tuesdays: Four Elections That Shaped the Twentieth Century (2015), compares 1912, 1932, 1968, 1992 in terms of social, economic, and political history

- Painter, Carl, "The Progressive Party In Indiana," Indiana Magazine of History, 16#3 (1920), pp. 173–283. In JSTOR

- Pinchot, Amos. History of the Progressive Party, 1912–1916. Introduction by Helene Maxwell Hooker. (New York University Press, 1958).

- Sarasohn, David. The Party of Reform: Democrats in the Progressive Era (UP of Mississippi, 1989), pp 119–154.

- Schambra, William. "The Election of 1912 and the Origins of Constitutional Conservatism." in Toward an American Conservatism (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013). 95-119.

- Selmi, Patrick. "Jane Addams and the Progressive Party Campaign for President in 1912." Journal of Progressive Human Services 22.2 (2011): 160–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428232.2010.540705

- Startt, James D. "Wilson's Election Campaign of 1912 and the Press." in Woodrow Wilson and the Press: Prelude to the Presidency (Palgrave Macmillan, 2004) pp. 197–228.

- Warner, Robert M. "Chase S. Osborn and the Presidential Campaign of 1912." Mississippi Valley Historical Review 46.1 (1959): 19-45. online

- Wilensky, Norman N. (1965). Conservatives in the Progressive Era: The Taft Republicans of 1912. Gainesville: University of Florida Press.

Primary sources

- Bryan, William Jennings. A Tale of Two Conventions: Being an Account of the Republican and Democratic National Conventions of June, 1912, with an Outline of the Progressive National Convention of August in the Same Year (Funk & Wagnalls Company, 1912). online

- Chester, Edward W A guide to political platforms (1977) online

- Pinchot, Amos. What's the Matter with America: The Meaning of the Progressive Movement and the Rise of the New Party. (Amos Pinchot, 1912).

- Roosevelt, Theodore. Theodore Roosevelt's Confession of Faith Before the Progressive National Convention, August 6, 1912 (Progressive Party, 1912) online.

- Roosevelt, Theodore. Bull Moose on the Stump: The 1912 Campaign Speeches of Theodore Roosevelt Ed. Lewis L. Gould. (UP of Kansas, 2008).

- Wilson, Woodrow (1956). John Wells Davidson (ed.). A Crossroads of Freedom, the 1912 Campaign Speeches.

- Porter, Kirk H. and Donald Bruce Johnson, eds. National party platforms, 1840-1964 (1965) online 1840-1956

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to United States presidential election, 1912. |

- United States presidential election of 1912 at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Presidential Election of 1912: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- editorial cartoons Archived February 15, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- Sound recording of TR speech

- OurCampaigns.com overview of Republican Presidential Primaries of 1912

- 1912 popular vote by counties

- 1912 State-by-state Popular vote

- The Election of 1912

- How close was the 1912 election? — Michael Sheppard, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Election of 1912 in Counting the Votes