Border states (American Civil War)

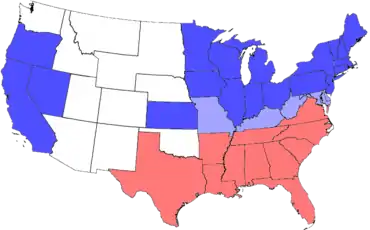

In the context of the American Civil War (1861–65), the border states were slave states that did not secede from the Union. They were Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri, and after 1863, the new state of West Virginia. To their north they bordered free states of the Union and to their south (except Delaware) they bordered Confederate slave states.

Of the 34 U.S. states in 1861, nineteen were free states and fifteen were slave states but compared to the states to their south, the border states held a low percentage enslaved persons.[1] Delaware, which had a comparatively small enslaved population, never declared a secession or adopted an ordinance. Maryland was largely prevented from seceding by local unionists and federal troops. Two others, Kentucky, and Missouri saw rival governments, although their territory mostly stayed in Union control. Four others did not declare secession until after the Battle of Fort Sumter and were briefly considered to be border states: Arkansas, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia—after this, they were less frequently called "border states". Also included as a border state during the war is West Virginia, which was formed from 50 counties of Virginia and became a new state in the Union in 1863.[2][3][4]

In civil war Kentucky, and Missouri, there were both pro-Confederate and pro-Union governments. West Virginia was formed in 1862–63 after Virginia Unionists from the northwestern counties of the state, then occupied by the Union Army consisting of many newly-formed West Virginia regiments, had set up a loyalist "restored" state government of Virginia. Lincoln recognized this government and allowed them to divide the state. Kentucky and Missouri had adopted secession ordinances by their pro-Confederate governments (see Confederate government of Kentucky and Confederate government of Missouri), but they never fully were under official Confederate control, though at various points Confederate armies did enter those states and controlled certain parts of them.

Besides formal combat between regular armies, the border region saw large-scale guerrilla warfare and numerous violent raids, feuds, and assassinations.[5] Violence was especially severe in West Virginia, eastern Kentucky and western Missouri. The single bloodiest episode was the 1863 Lawrence Massacre in Kansas, in which at least 150 civilian men and boys were killed. It was launched in retaliation for an earlier, smaller raid into Missouri by Union men from Kansas.[6][7]

With geographic, social, political, and economic connections to both the North and the South, the border states were critical to the outcome of the war. They are considered still to delineate the cultural border that separates the North from the South. Reconstruction, as directed by Congress, did not apply to the border states because they never seceded from the Union. They did undergo their own process of readjustment and political realignment after passage of amendments abolishing slavery and granting citizenship and the right to vote to freedmen. After 1880 most of these jurisdictions were dominated by white Democrats, who passed laws to impose the Jim Crow system of legal segregation and second-class citizenship for blacks. However, in contrast to the Confederate States, where almost all blacks were disenfranchised during the first half to two-thirds of the twentieth century, for varying reasons blacks remained enfranchised in the border states despite movements for disfranchisement during the 1900s.[8]

Lincoln's 1863 Emancipation Proclamation did not apply to the border states. Of the states that were exempted from the proclamation, Maryland (1864),[9] Missouri (1865),[10][11] Tennessee (1865),[11] and West Virginia (1865)[12] abolished slavery before the war ended. However, Delaware [13] and Kentucky did not see the abolition of slavery until December 1865, when the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified.[14]

Background

In the border states, slavery was already dying out in urban areas and the regions without cotton, especially in cities that were rapidly industrializing, such as Baltimore, Louisville, and St. Louis. By 1860, more than half of the African Americans in Delaware were free, as were a high proportion in Maryland.[15]

Some slaveholders made a profit by selling surplus slaves to traders for transport to the markets of the Deep South, where the demand was still high for field hands on cotton plantations.[16] In contrast to the near-unanimity of voters in the seven cotton states in the lower South, which held the highest number of slaves, the border slave states were bitterly divided about secession and were not eager to leave the Union. Border Unionists hoped that a compromise would be reached, and they assumed that Lincoln would not send troops to attack the South. Border secessionists paid less attention to the slavery issue in 1861, since their states' economies were based more on trade with the North than on cotton. Their main concern in 1861 was federal coercion; some residents viewed Lincoln's call to arms as a repudiation of the American traditions of states' rights, democracy, liberty, and a republican form of government. Secessionists insisted that Washington had usurped illegitimate powers in defiance of the Constitution, and thereby had lost its legitimacy.[4] After Lincoln issued a call for troops, Virginia, Tennessee, Arkansas, and North Carolina promptly seceded and joined the Confederacy. A secession movement began in western Virginia, where most farmers were yeomen and not slaveholders, to break away and remain in the Union.[17]

Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri, which had many areas with much stronger cultural and economic ties to the South than the North, were deeply divided;[18] Kentucky tried to maintain neutrality. Union military forces were used to guarantee that these states remained in the Union. The western counties of Virginia rejected secession, set up a loyal government of Virginia (with representation in the U.S. Congress), and created the new state of West Virginia (although it included many counties which had voted for secession).[17]

Divided loyalties

Though every slave state except South Carolina contributed white battalions to both the Union and Confederate armies (South Carolina Unionists fought in units from other Union states),[19] the split was most severe in these border states. Sometimes men from the same family fought on opposite sides. About 170,000 border state men (including African Americans) fought in the Union Army and 86,000 in the Confederate Army.[20] Thirty-five thousand Kentuckians served as Confederate soldiers; an estimated 125,000 Kentuckians served as Union soldiers.[21] By the end of the war in 1865, nearly 110,000 Missourians had served in the Union Army and at least 30,000 in the Confederate Army.[22] Some 50,000 citizens of Maryland signed up for the military, with most joining the United States Army. Approximately a tenth as many enlisted to "go South" and fight for the Confederacy. It has been estimated that, of the state's 1860 population of 687,000, about 4,000 Marylanders traveled south to fight for the Confederacy. While the number of Marylanders in Confederate service is often reported as 20,000–25,000 based on an oral statement of General Cooper to General Trimble, other contemporary reports refute this number and offer more detailed estimates in the range of 3,500 (Livermore)[23] to just under 4,700 (McKim).[24]

The five border states

Each of these five states shared a border with the free states and were aligned with the Union. All but Delaware also share borders with states that joined the Confederacy.

Delaware

By 1860 Delaware was integrated into the Northern economy, and slavery was rare except in the southern districts of the state; less than 2 percent of the population was enslaved.[25][26] Both houses of the state General Assembly rejected secession overwhelmingly; the House of Representatives was unanimous. There was quiet sympathy for the Confederacy by some state leaders, but it was tempered by distance; Delaware was bordered by Union territory. Historian John Munroe concluded that the average citizen of Delaware opposed secession and was "strongly Unionist" but hoped for a peaceful solution even if it meant Confederate independence.[27]

Maryland

Union troops had to go through Maryland to reach the national capital at Washington, D.C. Had Maryland also joined the Confederacy, Washington would have been surrounded. There was popular support for the Confederacy in Baltimore as well as in Southern Maryland and the Eastern Shore, where there were numerous slaveholders and slaves. Baltimore was strongly tied to the cotton trade and related businesses of the South. The Maryland Legislature rejected secession in the spring of 1861, though it refused to reopen rail links with the North. It requested that Union troops be removed from Maryland.[28] The state legislature did not want to secede, but it also did not want to aid in killing southern neighbors in order to force them back into the Union.[28] Maryland's wish for neutrality within the Union was a major obstacle given Lincoln's desire to force the South back into the Union militarily.

To protect the national capital, Lincoln suspended habeas corpus and imprisoned without charges or trials one sitting U.S. congressman as well the mayor, police chief, entire Board of Police, and the city council of Baltimore.[29] Chief Justice Roger Taney, acting only as a circuit judge, ruled on June 4, 1861, in Ex parte Merryman that Lincoln's suspension of habeas corpus was unconstitutional, but the president ignored the ruling in order to meet a national emergency. On September 17, 1861, the day the legislature reconvened, federal troops arrested without charge 27 state legislators (one-third of the Maryland General Assembly).[28][30] They were held temporarily at Fort McHenry, and later released when Maryland was secured for the Union. Because a large part of the legislature was now imprisoned, the session was canceled and representatives did not consider any additional anti-war measures. The song "Maryland, My Maryland" was written to attack Lincoln's action in blocking pro-Confederate elements. Maryland contributed troops to both the Union (60,000) and the Confederate (25,000) armies.

During the war, Maryland adopted a new state constitution in 1864 that prohibited slavery, thus emancipating all remaining slaves in the state.

Kentucky

Kentucky was strategic to Union victory in the Civil War. Lincoln once said,

I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game. Kentucky gone, we cannot hold Missouri, nor Maryland. These all against us, and the job on our hands is too large for us. We would as well consent to separation at once, including the surrender of this capitol [Washington, which was surrounded by slave states: Confederate Virginia and Union-controlled Maryland].[31]

Lincoln reportedly also declared, "I hope to have God on my side, but I must have Kentucky."[32]

Kentucky Governor Beriah Magoffin proposed that slave states such as Kentucky should conform to the US Constitution, and remain in the Union. When Lincoln requested 1,000,000 men to serve in the Union army, however, Magoffin, a Southern sympathizer, countered that "Kentucky had no troops to furnish for the wicked purpose of subduing her sister Southern States."[33] The Kentucky legislature did not vote on any bill to secede, but passed two resolutions of neutrality, issuing a neutrality proclamation May 20, 1861, asking both sides to keep out. In elections on June 20 and August 5, 1861, Unionists won enough additional seats in the legislature to overcome any veto by the governor. After the elections, the strongest supporters of neutrality were the Southern sympathizers. While both sides had already been openly enlisting troops from the state, after the elections the Union army established recruitment camps within Kentucky.

Neutrality was broken when Confederate General Leonidas Polk occupied Columbus, Kentucky, in the summer of 1861. In response, the Kentucky legislature passed a resolution on September 7 directing the governor to demand the evacuation of the Confederate forces from Kentucky soil. Magoffin vetoed the proclamation, but the legislature overrode his veto, and Magoffin issued the proclamation. The legislature decided to back General Ulysses S. Grant and his Union troops stationed in Paducah, Kentucky, on the grounds that the Confederacy voided the original pledge by entering Kentucky first. The General Assembly soon ordered the Union flag be raised over the state capitol in Frankfort, declaring its allegiance with the Union.

Southern sympathizers were outraged at the legislature's decisions, citing that Polk's troops in Kentucky were only en route to counter Grant's forces. Later legislative resolutions passed by Unionists—such as inviting Union General Robert Anderson to enroll volunteers to expel the Confederate forces, requesting the governor to call out the militia, and appointing Union General Thomas L. Crittenden in command of Kentucky forces—incensed the Southerners. (Magoffin vetoed the resolutions but was overridden each time.) In 1862, the legislature passed an act to disenfranchise citizens who enlisted in the Confederate States Army. Thus Kentucky's neutral status evolved into backing the Union. Most of those who originally sought neutrality turned to the Union cause.

During the war, a faction known as the Russellville Convention formed a Confederate government of Kentucky, which was recognized by the Confederate States of America as a member state. Kentucky was represented by the central star on the Confederate battle flag.[34]

When Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston occupied Bowling Green, Kentucky, in the summer of 1861, the pro-Confederates in western and central Kentucky moved to establish a Confederate state government in that area. The Russellville Convention met in Logan County on November 18, 1861. One hundred and sixteen delegates from sixty-eight counties elected to depose the current government, and create a provisional government loyal to Kentucky's new unofficial Confederate Governor, George W. Johnson. On December 10, 1861, Kentucky became the 13th state admitted to the Confederacy. Kentucky, along with Missouri, was a state with representatives in both Congresses, and with regiments in both Union and Confederate armies.

Magoffin, still functioning as official governor in Frankfort, would not recognize the Kentucky Confederates, nor their attempts to establish a government in his state. He continued to declare Kentucky's official status in the war as a neutral state—even though the legislature backed the Union. Fed up with the party divisions within the population and legislature, Magoffin announced a special session of the legislature, and resigned his office in 1862.

Bowling Green was occupied by the Confederates until February 1862, when General Grant moved from Missouri, through Kentucky, along the Tennessee line. Confederate Governor Johnson fled Bowling Green with the Confederate state records, headed south, and joined Confederate forces in Tennessee. After Johnson was killed fighting in the Battle of Shiloh, Richard Hawes was named Confederate governor of Kentucky. Shortly afterwards, the Provisional Confederate States Congress was adjourned on February 17, 1862, on the eve of inauguration of a permanent Congress. However, as Union occupation dominated the state after the failure of the Confederate Heartland Offensive to firmly take Kentucky from August to October 1862, the Kentucky Confederate government, as of 1863, existed only on paper. Its representation in the permanent Confederate Congress was minimal. It was dissolved when the Civil War ended in the spring of 1865.

Missouri

After the secession of Southern states began, the newly elected governor of Missouri, Claiborne F. Jackson, called upon the legislature to authorize a state constitutional convention on secession. A special election approved of the convention, and delegates to it. This Missouri Constitutional Convention voted to remain within the Union, but rejected coercion of the Southern states by the United States.

Jackson, who was pro-Confederate, was disappointed with the outcome. He called up the state militia to their districts for annual training. Jackson had designs on the St. Louis Arsenal, and had been in secret correspondence with Confederate President Jefferson Davis to obtain artillery for the militia in St. Louis. Aware of these developments, Union Captain Nathaniel Lyon struck first, encircling the camp and forcing the state militia to surrender. While his troops were marching the prisoners to the arsenal, a deadly riot erupted (the Camp Jackson Affair).

These events resulted in greater Confederate support within the state among some factions. The already pro-Southern Missouri State Legislature passed the governor's military bill creating the Missouri State Guard. Governor Jackson appointed Sterling Price, who had been president of the convention, as major general of this reformed militia. Price, and Union district commander Harney, came to an agreement known as the Price–Harney Truce, which calmed tensions in the state for several weeks. After Harney was removed, and Lyon placed in charge, a meeting was held in St. Louis at the Planters' House among Lyon, his political ally Francis P. Blair, Jr., Price, and Jackson. The negotiations went nowhere. After a few fruitless hours, Lyon declared, "this means war!" Price and Jackson rapidly departed for the capital.

Jackson, Price, and the pro-Confederate portions of the state legislature were forced to flee the state capital of Jefferson City on June 14, 1861, in the face of Lyon's rapid advance against the state government. In the absence of most of the now exiled state government, the Missouri Constitutional Convention reconvened in late July. On July 30, the convention declared the state offices vacant, and appointed a new provisional government with Hamilton Gamble as governor. President Lincoln's administration immediately recognized the legitimacy of Gamble's government, which provided both pro-Union militia forces for service within the state, and volunteer regiments for the Union Army.[35]

Fighting ensued between Union forces and a combined army of General Price's Missouri State Guard and Confederate troops from Arkansas and Texas, under General Ben McCulloch. After a string of victories in Cole Camp, Carthage, Wilson's Creek, Dry Wood Creek, Liberty and going up as far north as Lexington (located in the Missouri River Valley region of western Missouri), the secessionist forces retreated to southwestern Missouri, as they were under pressure from Union reinforcements. On October 30, 1861, in the town of Neosho, Jackson called the supporting parts of the exiled state legislature into session, where they enacted a secession ordinance. It was recognized by the Confederate Congress, and Missouri was admitted into the Confederacy on November 28.

The exiled state government was forced to withdraw into Arkansas. For the rest of the war, it consisted of several wagon loads of civilian politicians attached to various Confederate armies. In 1865, it vanished.

Missouri abolished slavery during the war in January 1865.

Guerrilla warfare

Regular Confederate troops staged several large-scale raids into Missouri, but most of the fighting in the state for the next three years consisted of guerrilla warfare. The guerrillas were primarily Southern partisans, including William Quantrill, Frank and Jesse James, the Younger brothers, and William T. Anderson, and many personal feuds were played out in the violence.[36] Small-unit tactics pioneered by the Missouri Partisan Rangers were used in occupied portions of the Confederacy during the Civil War.[37]

The James' brothers outlawry after the war has been seen as a continuation of guerrilla warfare. Stiles (2002) argues that Jesse James was an intensely political postwar neo-Confederate terrorist, rather than a social bandit or a plain bank robber with a hair-trigger temper.[38]

The Union response was to suppress the guerrillas.[37]:81–96 It achieved that in western Missouri, as Brigadier General Thomas Ewing issued General Order No. 11 on 25 August 1863 in response to Quantrill's raid on Lawrence, Kansas. The order forced the total evacuation of four counties that fall within the area of modern-day Kansas City, Missouri. These had been centers of local support for the guerrillas. Lincoln approved Ewing's plan beforehand. About 20,000 civilians (chiefly women, children, and old men) had to leave their homes. Many never returned, and the counties were economically devastated for years.

According to Glatthaar (2001), Union forces established "free-fire zones". Union cavalry units would identify and track down scattered Confederate remnants, who had no places to hide and no secret supply bases.[39] To gain recruits, and to threaten St. Louis, Confederate General Sterling Price raided Missouri with 12,000 men in September/October 1864. Price coordinated his moves with the guerrillas, but was nearly trapped, escaping to Arkansas with only half his force after a decisive Union victory at the Battle of Westport. The battle, which took place in the modern-day Westport neighborhood of Kansas City, is identified as the "Gettysburg of the West"; it marked a definitive end to organized Confederate incursions inside Missouri's borders. The Republicans made major gains in the fall 1864 elections on the basis of Union victories and Confederate ineptness.[40] Quantrill's Raiders, after raiding Kansas in the Lawrence Massacre on August 21, 1863, killing 150 civilians, broke up in confusion. Quantrill and a handful of followers moved on to Kentucky, where he was ambushed and killed.

West Virginia

The serious divisions between the western and eastern sections of Virginia had been simmering for decades, related to class and social differences. The western areas were growing and were based on subsistence farms by yeomen; its residents held few slaves. The planters of the eastern section were wealthy slaveholders who dominated state government.[41] By December 1860 secession was being publicly debated throughout Virginia. Leading eastern spokesmen called for secession, while westerners warned they would not be legislated into treason. A statewide convention first met on February 13; after the attack on Fort Sumter and Lincoln's call to arms, it voted for secession on April 17, 1861. The decision was dependent on ratification by a statewide referendum. Western leaders held mass rallies and prepared to separate, so that this area could remain in the Union. Unionists met at the Wheeling Convention with four hundred delegates from twenty-seven counties. The statewide vote in favor of secession was 132,201 to 37,451. An estimated vote on Virginia's ordinance of secession for the 50 counties that became West Virginia is 34,677 to 19,121 against secession, with 24 of the 50 counties favoring secession and 26 favoring the Union.[42]

The Second Wheeling Convention opened on June 11 with more than 100 delegates from 32 western counties; they represented nearly one-third of Virginia's total voting population.[43] It announced that state offices were vacant and chose Francis H. Pierpont as governor of Virginia (not West Virginia) on June 20. Pierpont headed the Restored Government of Virginia, which granted permission for the formation of a new state on August 20, 1861. The new West Virginia state constitution was passed by the Unionist counties in the spring of 1862, and this was approved by the restored Virginia government in May 1862. The statehood bill for West Virginia was passed by the United States Congress in December and signed by President Lincoln on December 31, 1862.[44]

The ultimate decision about West Virginia was made by the armies in the field. The Confederates were defeated, the Union was triumphant, so West Virginia was born. In late spring 1861 Union troops from Ohio moved into western Virginia with the primary strategic goal of protecting the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. General George B. McClellan destroyed Confederate defenses in western Virginia. Raids and recruitment by the Confederacy took place throughout the war.[45] Current estimates of soldiers from West Virginia are 20,000-22,000 men each to the Union and the Confederacy.[46]

West Virginia was required as part of its admission as a state to have a gradual emancipation clause in the new state's constitution.[47][48] It later completely abolished slavery before the end of the war.[49]

The unique conditions attendant to the creation of the state led the Federal government to sometimes regard West Virginia as differing from the other border states in the post-war and Reconstruction Era. The terms of surrender granted to the Confederate army at Appomattox applied to the soldiers of the 11 Confederate states and West Virginia only. Returning Confederate soldiers from the other border states were required to obtain special permits from the War Department.[50] Similarly, the Southern Claims Commission was originally designed to apply only to the 11 Confederate states and West Virginia, though claims from other states were sometimes honored.

Other border areas

Tennessee

Though Tennessee had officially seceded and West Tennessee and Middle Tennessee had voted overwhelmingly in favor of joining the Confederacy, East Tennessee in contrast was strongly pro-Union and had mostly voted against secession. The state even went as far as sending delegates for the East Tennessee Convention attempting to secede from the Confederacy and join the Union; however, the Confederate legislature of Tennessee rejected the convention and blocked its secession attempt. Jefferson Davis arrested over 3,000 men suspected of being loyal to the Union and held them without trial.[51] Tennessee came under control of Union forces in 1862 and was occupied to the end of the war. For this reason, it was omitted from the Emancipation Proclamation. After the war, Tennessee was the first Confederate state to have its elected members readmitted to the US Congress.

Indian Territory

In the Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), most Indian tribes owned black slaves, and they sided with the Confederacy. It had promised them an Indian state if victorious in the war. But some tribes and bands sided with the Union. A bloody civil war resulted in the territory, with severe hardships for all residents.[52][53]

Kansas

After years of small-scale civil war, Kansas was admitted into the Union as a free state under the "Wyandotte Constitution" on January 29, 1861. Most people gave strong support to the Union cause. However, guerrilla warfare and raids from pro-slavery forces, many spilling over from Missouri, occurred during the Civil War.[54] Although only one battle of official forces occurred in Kansas, there were 29 Confederate raids into the state during the war and numerous deaths caused by the guerrillas.[55] Lawrence came under attack on August 21, 1863, by guerrillas led by William Clarke Quantrill. He was retaliating for "Jayhawker" raids against pro-Confederate settlements in Missouri.[5][56][57] His forces left more than 150 people dead in Lawrence.

New Mexico/Arizona Territory

At the time the Civil War broke out, the present-day states of New Mexico and Arizona did not yet exist. There were various proposals, however, to create a new territory within the southern half of the New Mexico Territory prior to the war. The southern half of the territory was pro-Confederate while the northern half was pro-Union. The southern half was also a target of Confederate Texan forces under Charles L. Pyron and Henry Hopkins Sibley, who attempted to establish control there. They had plans to attack the Union states of California and Colorado Territory (both of which also had Southern sympathizers) as well as the eastern side of the Rocky Mountains, Fort Laramie, and Nevada Territory, followed by an invasion of the Mexican states of Chihuahua, Sonora, and Lower California. Ultimately their defeat at the Battle of Glorieta Pass prevented these plans from fruition and Sibley's Confederates fled back to East Texas.

See also

References

- "The Border States (U.S. National Park Service)". National Park Service. Retrieved 2020-07-08.

- Maury Klein, Days of Defiance: Sumter, Secession, and the Coming of the Civil War (Knopf, 1997) p 22.

- In 1861, "From February into the late spring, North Carolina, Virginia, Tennessee, and Arkansas were considered border states," says David Stephen Heidler et al., eds. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War (2002) p. 252.

- Daniel W. Crofts, Reluctant Confederates: Upper South Unionists in the Secession Crisis pp. 101-101 ISBN 1469617013

- Daniel E. Sutherland, A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War; pp. 251–276 ISBN 1469606887

- Fellman, Michael (1989). Inside War: The Guerrilla Conflict in Missouri in the American Civil War. ISBN 0-19-506471-2. p. 25.

- "The Lawrence Massacre by a Band of Missouri Ruffians Under Quantrell". J. S. Broughton. Retrieved 2015-02-19.

- Ranney, Joseph A.; In the Wake of Slavery: Civil War, Civil Rights, and the Reconstruction of Southern Law; p. 141 ISBN 0275989720

- "Archives of Maryland Historical List: Constitutional Convention, 1864". November 1, 1864.

- "Missouri abolishes slavery". January 11, 1865.

- "TENNESSEE STATE CONVENTION: Slavery Declared Forever Abolished; Emancipation Rejoicings in St. Louis". The New York Times. January 14, 1865.

- "On this day: 1865-FEB-03". Archived from the original on 2014-10-08.

- "Slavery in Delaware".

- Lowell Hayes Harrison & James C. Klotter (1997). A new history of Kentucky. p. 180. ISBN 0813126215. In 1866, Kentucky refused to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment. It did ratify it in 1976.

- In nine of the ten chief southern cities, the proportion of slaves steadily declined before the war. The exception was Richmond, Virginia. Midori Takagi, "Rearing Wolves to Our Own Destruction": Slavery in Richmond, Virginia, 1782–1865 (University Press of Virginia, 1999) p 78.

- Allan Nevins, The Emergence of Lincoln: Prologue to Civil War, 1859–1861 (1950) pages 149–55

- Allan Nevins, The Emergence of Lincoln: Prologue to Civil War, 1859–1861 (1950), pp. 119–47

- Brugger, J. Robert (1996). Maryland, A Middle Temperament. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 248. ISBN 0801854652.

- Current, Richard Nelson (1992). Lincoln's Loyalists: Union Soldiers from the Confederacy. UPNE. p. 5.

except south carolina.

- James M. McPherson, Ordeal by Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction (1982), pp 156–62.

- Quisenberry, A. C. "Kentucky Union Troops in the Civil War". Register of the Kentucky State Historical Society, vol. 18, no. 54, 1920, pp. 13–18. JSTOR stable/23369562.

- American Civil War in Missouri Research Guide You must click "Regimental Histories" to access the data.

- Thomas Livermore, Numbers and Losses in the Civil War, Boston, 1900. See chart and explanation, p. 550

- Randolph McKim, Numerical Strength of the Confederate Army, New York, 1912

- Kolchin, Peter. American Slavery: 1619-1877. Hill & Wang, 1993

- "Slavery, the Civil War, and Reconstruction". Britannica.com. 2014-01-22. Retrieved 2014-03-31.

- John A. Munroe (2006). History of Delaware. U. of Delaware Press. pp. 132–34. ISBN 9780874139471.

- "Teaching American History in Maryland – Documents for the Classroom: Arrest of the Maryland Legislature, 1861". Maryland State Archives. 2005. Archived from the original on January 11, 2008. Retrieved February 6, 2008.

- "Fort McHenry, Lincoln Suspension of Habeas Corpus", Baltimore Sun, 27 November 2001

- William C. Harris, Lincoln and the Border States: Preserving the Union (University Press of Kansas, 2011) p. 71

- Roy P. Basler; Marion Dolores Pratt; Lloyd A. Dunlap, assistant, eds. (2001). "Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. Volume 4". University of Michigan Digital Library Production Services. p. 533. Retrieved 2011-05-28.

- Encyclopedia of Kentucky, p.43.

- "KENTUCKY.; SECESSION MESSAGE OF GOV. MAGOFFIN, TO THE LEGISLATURE IN SPECIAL SESSION. Gentlemen of the Senate and House of Representatives". Digitized version of an article from The Times’s print archive. New York Time. May 11, 1861. p. 9. Retrieved 2020-08-04.

- Irby, Jr., Richard E. "A Concise History of the Flags of the Confederate States of America and the Sovereign State of Georgia". About North Georgia. Golden Ink. Retrieved 2006-11-29.

- Parrish, William E.; Turbulent Partnership: Missouri and the Union, 1861–1865, p. 198. University of Missouri Press, 1963

- Larry Wood, "The Other Anderson: Bloody Bill's Brother Jim," Missouri Historical Review, January 2003, Vol. 97 Issue 2, pp 93-108

- Michael Fellman, Inside War: The Guerrilla Conflict in Missouri During the American Civil War, p. 83 ISBN 0195064712

- T. J. Stiles, Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War (2002)

- Joseph T. Glatthaar, The American Civil War: The War in the West, 1863–1865 (2001) p. 27–28

- Parrish, History of Missouri, pp. 111–15

- Charles H. Ambler and Festus P. Summers, West Virginia, the Mountain State (1958) ch. 16-21

- Curry, Richard O., A House Divided, A Study of Statehood Politics and the Copperhead Movement in West Virginia, University of Pittsburgh, 1964, pp. 142-147

- Ambler, The History of West Virginia, p. 318

- Curry "A Reappraisal of Statehood Politics in West Virginia" p. 407

- Richard O. Curry, A House Divided (1964)

- Snell, Mark A., West Virginia and the Civil War, History Press, Charleston, SC (2011), p. 28

- James Oakes, Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861–1865, W.W. Norton, 2012, pgs. 296-97

- "West Virginians Approve the Willey Amendment". wvculture.org. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- "On This Day in West Virginia History – February 3". wvculture.org. Archived from the original on October 8, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- "General Orders No. 57, Brevet Major General Emory". Wvculture.org. Retrieved 2014-03-31.

- Mark Neely, Confederate Bastille: Jefferson Davis and Civil Liberties (1993), pp. 10–11

- Annie Heloise Abel, "The Indians in the Civil War", American Historical Review Vol. 15, No. 2 (Jan. 1910), pp. 281-296 in JSTOR

- John Spencer and Adam Hook, The American Civil War in Indian Territory (2006)

- Gary L. Cheatham, "'Slavery All the Time or Not At All': The Wyandotte Constitution Debate, 1859–1861," Kansas History 21 (Autumn 1998): 168–187 online

- Gary L. Cheatham, "'Desperate Characters': The Development and Impact of the Confederate Guerrillas In Kansas," Kansas History, September 1991, Vol. 14 Issue 3, pp 144-161

- Albert Castel, "The Jayhawkers and Copperheads of Kansas", Civil War History, September 1959, Vol. 5 Issue 3, pp 283-293

- Donald Gilmore, "Revenge in Kansas, 1863", History Today, March 1993, Vol. 43 Issue 3, pp 47-53

Further reading

- Brownlee, Richard S. Gray Ghosts of the Confederacy: Guerrilla Warfare in the West, 1861–1865 (1958) online

- Crofts, Daniel W. Reluctant Confederates: Upper South Unionists in the Secession Crisis. (1989).

- Dew, Charles B. Apostles of disunion: Southern secession commissioners and the causes of the Civil War (U of Virginia Press, 2017).

- Eli, Shari, Laura Salisbury, and Allison Shertzer. "Migration responses to conflict: evidence from the border of the American Civil war" (No. w22591. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2016) online

- Harris, William C. Lincoln and the Border States: Preserving the Union (University Press of Kansas; 2011) 416 pages

- Nevins, Allan. The War for the Union: The Improvised War 1861–1862. (1959).

- Phillips, Christopher. The Rivers Ran Backward: The Civil War and the Remaking of the American Middle Border (Oxford UP, 2016).

- Robinson, Michael D. A Union Indivisible: Secession and the Politics of Slavery in the Border South (2017)

- Sutherland, Daniel E. A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War (U. of North Carolina Press, 2008) 456 pp

External links

- Mr. Lincoln and Freedom: Border States

- Thomas, William G., III. “The Border South”. Southern Spaces, April 16, 2004.