Cormorant

Phalacrocoracidae is a family of approximately 40 species of aquatic birds commonly known as cormorants and shags. Several different classifications of the family have been proposed recently and the number of genera is disputed. The great cormorant (P. carbo) and the common shag (P. aristotelis) are the only two species of the family commonly encountered on the British Isles[1] and "cormorant" and "shag" appellations have been later assigned to different species in the family somewhat haphazardly.

| Cormorants and shags | |

|---|---|

| |

| Little pied cormorant Microcarbo melanoleucos | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Suliformes |

| Family: | Phalacrocoracidae Reichenbach, 1850 |

| Genera | |

|

See text | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Australocorax Lambrecht, 1931 | |

Cormorants and shags are medium-to-large birds, with body weight in the range of 0.35–5 kilograms (0.77–11.02 lb) and wing span of 45–100 centimetres (18–39 in). The majority of species have dark feathers. The bill is long, thin and hooked. Their feet have webbing between all four toes. All species are fish-eaters, catching the prey by diving from the surface. They are excellent divers, and under water they propel themselves with their feet with help from their wings; some cormorant species have been found to dive as deep as 45 metres (150 ft). They have relatively short wings due to their need for economical movement underwater, and consequently have the highest flight costs of any flying bird.[2]

Cormorants nest in colonies around the shore, on trees, islets or cliffs. They are coastal rather than oceanic birds, and some have colonised inland waters. The original ancestor of cormorants seems to have been a fresh-water bird. They range around the world, except for the central Pacific islands.

Names

No consistent distinction exists between cormorants and shags. The names 'cormorant' and 'shag' were originally the common names of the two species of the family found in Great Britain, Phalacrocorax carbo (now referred to by ornithologists as the great cormorant) and P. aristotelis (the European shag). "Shag" refers to the bird's crest, which the British forms of the great cormorant lack. As other species were encountered by English-speaking sailors and explorers elsewhere in the world, some were called cormorants and some shags, depending on whether they had crests or not. Sometimes the same species is called a cormorant in one part of the world and a shag in another, e.g., the great cormorant is called the black shag in New Zealand (the birds found in Australasia have a crest that is absent in European members of the species). Van Tets (1976) proposed to divide the family into two genera and attach the name "cormorant" to one and "shag" to the other, but this flies in the face of common usage and has not been widely adopted.

The scientific genus name is Latinised Ancient Greek, from φαλακρός (phalakros, "bald") and κόραξ (korax, "raven").[3] This is often thought to refer to the creamy white patch on the cheeks of adult great cormorants, or the ornamental white head plumes prominent in Mediterranean birds of this species, but is certainly not a unifying characteristic of cormorants. "Cormorant" is a contraction derived either directly from Latin corvus marinus, "sea raven" or through Brythonic Celtic. Cormoran is the Cornish name of the sea giant in the tale of Jack the Giant Killer. Indeed, "sea raven" or analogous terms were the usual terms for cormorants in Germanic languages until after the Middle Ages. The French explorer André Thévet commented in 1558, "... the beak [is] similar to that of a cormorant or other corvid," which demonstrates that the erroneous belief that the birds were related to ravens lasted at least to the 16th century.

Description

Cormorants and shags are medium-to-large seabirds. They range in size from the pygmy cormorant (Phalacrocorax pygmaeus), at as little as 45 cm (18 in) and 340 g (12 oz), to the flightless cormorant (Phalacrocorax harrisi), at a maximum size 100 cm (39 in) and 5 kg (11 lb). The recently extinct spectacled cormorant (Phalacrocorax perspicillatus) was rather larger, at an average size of 6.3 kg (14 lb). The majority, including nearly all Northern Hemisphere species, have mainly dark plumage, but some Southern Hemisphere species are black and white, and a few (e.g. the spotted shag of New Zealand) are quite colourful. Many species have areas of coloured skin on the face (the lores and the gular skin) which can be bright blue, orange, red or yellow, typically becoming more brightly coloured in the breeding season. The bill is long, thin, and sharply hooked. Their feet have webbing between all four toes, as in their relatives.

Habitat

They are coastal rather than oceanic birds, and some have colonised inland waters – indeed, the original ancestor of cormorants seems to have been a fresh-water bird, judging from the habitat of the most ancient lineage. They range around the world, except for the central Pacific islands.

Behaviour

All are fish-eaters, dining on small eels, fish, and even water snakes. They dive from the surface, though many species make a characteristic half-jump as they dive, presumably to give themselves a more streamlined entry into the water. Under water they propel themselves with their feet, though some also propel themselves with their wings (see the picture,[4] commentary,[5] and existing reference video[6]). Some cormorant species have been found, using depth gauges, to dive to depths of as much as 45 metres (150 ft).

After fishing, cormorants go ashore, and are frequently seen holding their wings out in the sun. All cormorants have preen gland secretions that are used ostensibly to keep the feathers waterproof. Some sources[7] state that cormorants have waterproof feathers while others say that they have water-permeable feathers.[8][9] Still others suggest that the outer plumage absorbs water but does not permit it to penetrate the layer of air next to the skin.[10] The wing drying action is seen even in the flightless cormorant but not in the Antarctic shags[11] or red-legged cormorants. Alternate functions suggested for the spread-wing posture include that it aids thermoregulation[12] or digestion, balances the bird, or indicates presence of fish. A detailed study of the great cormorant concludes that it is without doubt[13] to dry the plumage.[14][15]

Cormorants are colonial nesters, using trees, rocky islets, or cliffs. The eggs are a chalky-blue colour. There is usually one brood a year. Parents regurgitate food to feed their young, whose deep, ungainly bills show a greater resemblance to those of the pelicans (to which they are related) than is obvious in the adults.

Taxonomy

The cormorants are a group traditionally placed within the Pelecaniformes or, in the Sibley–Ahlquist taxonomy, the expanded Ciconiiformes. This latter group is certainly not a natural one, and even after the tropicbirds have been recognised as quite distinct, the remaining Pelecaniformes seem not to be entirely monophyletic. Their relationships and delimitation – apart from being part of a "higher waterfowl" clade which is similar but not identical to Sibley and Ahlquist's "pan-Ciconiiformes" – remain mostly unresolved. Notwithstanding, all evidence agrees that the cormorants and shags are closer to the darters and Sulidae (gannets and boobies), and perhaps the pelicans or even penguins, than to all other living birds.[16]

In recent years, three preferred treatments of the cormorant family have emerged: either to leave all living cormorants in a single genus, Phalacrocorax, or to split off a few species such as the imperial shag complex (in Leucocarbo) and perhaps the flightless cormorant. Alternatively, the genus may be disassembled altogether and in the most extreme case be reduced to the great, white-breasted and Japanese cormorants.[17]

Pending a thorough review of the Recent and prehistoric cormorants, the single-genus approach[18] is followed here for three reasons: first, it is preferable to tentatively assigning genera without a robust hypothesis. Second, it makes it easier to deal with the fossil forms, the systematic treatment of which has been no less controversial than that of living cormorants and shags. Third, this scheme is also used by the IUCN,[19] making it easier to incorporate data on status and conservation. In accordance with the treatment there, the imperial shag complex is here left unsplit as well, but the king shag complex has been.

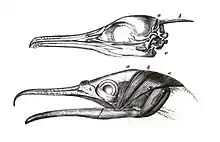

The cormorants and the darters have a unique bone on the back of the top of the skull known as the os nuchale or occipital style which was called a xiphoid process in early literature. This bony projection provides anchorage for the muscles that increase the force with which the lower mandible is closed.[20][21] This bone and the highly developed muscles over it, the M. adductor mandibulae caput nuchale, are unique to the families Phalacrocoracidae and Anhingidae.[22][23]

Several evolutionary groups are still recognizable. However, combining the available evidence suggests that there has also been a great deal of convergent evolution; for example the cliff shags are a convergent paraphyletic group. The proposed division into Phalacrocorax sensu stricto (or subfamily "Phalacrocoracinae") cormorants and Leucocarbo sensu lato (or "Leucocarboninae") shags[24] does have some degree of merit.[25] The resolution provided by the mtDNA 12S rRNA and ATPase subunits six and eight sequence data[25] is not sufficient to properly resolve several groups to satisfaction; in addition, many species remain unsampled, the fossil record has not been integrated in the data, and the effects of hybridisation – known in some Pacific species especially – on the DNA sequence data are unstudied.

List of genera

_-_Weltvogelpark_Walsrode_2012-01.jpg.webp)

The family contains three genera:[26] For details, see the article "List of cormorant species"

- Microcarbo (5 species)

- Phalacrocorax (22 species, including one extinct in 19th century)

- Leucocarbo (15 species)

Evolution and fossil record

Cormorants seem to be a very ancient group, with similar ancestors reaching back to the time of the dinosaurs. In fact, the earliest known modern bird, Gansus yumenensis, had essentially the same structure. The details of the evolution of the cormorant are mostly unknown. Even the technique of using the distribution and relationships of a species to figure out where it came from, biogeography, usually very informative, does not give very specific data for this probably rather ancient and widespread group. However, the closest living relatives of the cormorants and shags are the other families of the suborder Sulae—darters and gannets and boobies—which have a primarily Gondwanan distribution. Hence, at least the modern diversity of Sulae probably originated in the southern hemisphere.

While the Leucocarbonines are almost certainly of southern Pacific origin—possibly even the Antarctic which, at the time when cormorants evolved, was not yet ice-covered—all that can be said about the Phalacrocoracines is that they are most diverse in the regions bordering the Indian Ocean, but generally occur over a large area.

Similarly, the origin of the family is shrouded in uncertainties. Some Late Cretaceous fossils have been proposed to belong with the Phalacrocoracidae:

A scapula from the Campanian-Maastrichtian boundary, about 70 mya (million years ago), was found in the Nemegt Formation in Mongolia; it is now in the PIN collection.[27] It is from a bird roughly the size of a spectacled cormorant, and quite similar to the corresponding bone in Phalacrocorax. A Maastrichtian (Late Cretaceous, c. 66 mya) right femur, AMNH FR 25272 from the Lance Formation near Lance Creek, Wyoming, is sometimes suggested to be the second-oldest record of the Phalacrocoracidae; this was from a rather smaller bird, about the size of a long-tailed cormorant.[28]

As the Early Oligocene Sula" ronzoni cannot be assigned to any of the suloid families—cormorants and shags, darters, and gannets and boobies—with certainty, the best interpretation is that the Phalacrocoracidae diverged from their closest ancestors in the Early Oligocene, perhaps some 30 million years ago, and that the Cretaceous fossils represent ancestral suloids, "pelecaniforms" or "higher waterbirds"; at least the last lineage is generally believed to have been already distinct and undergoing evolutionary radiation at the end of the Cretaceous. What can be said with near certainty is that AMNH FR 25272 is from a diving bird that used its feet for underwater locomotion; as this is liable to result in some degree of convergent evolution and the bone is missing indisputable neornithine features, it is not entirely certain that the bone is correctly referred to this group.[29]

During the late Paleogene, when the family presumably originated, much of Eurasia was covered by shallow seas, as the Indian Plate finally attached to the mainland. Lacking a detailed study, it may well be that the first "modern" cormorants were small species from eastern, south-eastern or southern Asia, possibly living in freshwater habitat, that dispersed due to tectonic events. Such a scenario would account for the present-day distribution of cormorants and shags and is not contradicted by the fossil record; as remarked above, a thorough review of the problem is not yet available.

Two distinct genera of prehistoric cormorants are widely accepted today, if Phalacrocorax is used for all living species:

- Limicorallus (Indricotherium middle Oligocene of Chelkar-Teniz, Kazakhstan)

- Nectornis (Late Oligocene/Early Miocene of Central Europe – Middle Miocene of Bes-Konak, Turkey) – includes Oligocorax miocaenus

The proposed genus Oligocorax appears to be paraphyletic – the European species have been separated in Nectornis, and the North American ones are placed in the expanded Phalacrocorax. A Late Oligocene fossil cormorant foot from Enspel, Germany, sometimes placed herein, would then be referable to Nectornis if it proves not to be too distinct. All these early European species might belong to the basal group of "microcormorants", as they conform with them in size and seem to have inhabited the same habitat: subtropical coastal or inland waters. Limicorallus, meanwhile, was initially believed to be a rail or a dabbling duck by some. There are also undescribed remains of apparent cormorants from the Quercy Phosphorites of Quercy (France), dating to some time between the Late Eocene and the mid-Oligocene.

Some other Paleogene remains are sometimes assigned to the Phalacrocoracidae, but these birds seem quite intermediate between cormorants and darters (and lack clear autapomorphies of either). Thus, they may be quite basal members of the Palacrocoracoidea. The taxa in question are:

- Piscator (Late Eocene of England)

- "Pelecaniformes" gen. et sp. indet. (Jebel Qatrani Early Oligocene of Fayum, Egypt) – similar to Piscator?

- Borvocarbo (Late Oligocene of C Europe)

The supposed Late Pliocene/Early Pleistocene "Valenticarbo" is a nomen dubium and given its recent age probably not a separate genus.

The remaining species are, in accordance with the scheme used in this article, all placed in the modern genus Phalacrocorax:

- Phalacrocorax marinavis (Oligocene – Early Miocene of Oregon, US) – formerly Oligocorax

- Phalacrocorax littoralis (Late Oligocene/Early Miocene of St-Gérand-le-Puy, France) – formerly Oligocorax, might belong into Nectornis

- Phalacrocorax intermedius (Early – Middle Miocene of C Europe) – includes P. praecarbo, Ardea/P. brunhuberi and Botaurites avitus

- Phalacrocorax macropus (Early Miocene – Pliocene of north-west US)

- Phalacrocorax ibericus (Late Miocene of Valles de Fuentiduena, Spain)

- Phalacrocorax lautus (Late Miocene of Golboçica, Moldavia)

- Phalacrocorax serdicensis (Late Miocene of Hrabarsko, Bulgaria)

- Phalacrocorax femoralis (Modelo Late Miocene/Early Pliocene of WC North America) – formerly Miocorax

- Phalacrocorax sp. (Late Miocene/Early Pliocene of Lee Creek Mine, US)

- Phalacrocorax longipes (Late Miocene – Early Pliocene of the Ukraine) – formerly Pliocarbo

- Phalacrocorax goletensis (Early Pliocene – Early Pleistocene of Mexico)

- Phalacrocorax wetmorei (Bone Valley Early Pliocene of Florida)

- Phalacrocorax sp. (Bone Valley Early Pliocene of Polk County, Florida, US)[30]

- Phalacrocorax leptopus (Juntura Early/Middle Pliocene of Juntura, Malheur County, Oregon, US)

- Phalacrocorax idahensis (Middle Pliocene – Pleistocene of Idaho, US)

- Phalacrocorax destefanii (Late Pliocene of Italy) – formerly Paracorax

- Phalacrocorax filyawi (Pinecrest Late Pliocene of Florida, US) – may be P. idahensis

- Phalacrocorax kumeyaay (San Diego Late Pliocene of California, US)

- Phalacrocorax macer (Late Pliocene of Idaho, US)

- Phalacrocorax mongoliensis (Late Pliocene of W Mongolia)

- Phalacrocorax rogersi (Late Pliocene – Early Pleistocene of California, US)

- Phalacrocorax kennelli (San Diego Pliocene of California, US)

- Phalacrocorax sp. "Wildhalm" (Pliocene) – may be same as P. longipes[31]

- Phalacrocorax chapalensis (Late Pliocene/Early Pleistocene of Jalisco, Mexico

- Phalacrocorax gregorii (Late Pleistocene of Australia) – possibly not a valid species

- Phalacrocorax vetustus (Late Pleistocene of Australia) – formerly Australocorax, possibly not a valid species

- Phalacrocorax reliquus

- Phalacrocorax sp. (Sarasota County, Florida, US) – may be P. filawyi/idahensis

The former "Phalacrocorax" (or "Oligocorax") mediterraneus is now considered to belong to the bathornithid Paracrax antiqua.[32] "P." subvolans was actually a darter (Anhinga).

In human culture

Cormorant fishing

Humans have used cormorants' fishing skills in various places in the world. Archaeological evidence suggests that cormorant fishing was practised in Ancient Egypt, Peru, Korea and India, but the strongest tradition has remained in China and Japan, where it reached commercial-scale level in some areas.[33] In Japan, cormorant fishing is called ukai (鵜飼). Traditional forms of ukai can be seen on the Nagara River in the city of Gifu, Gifu Prefecture, where cormorant fishing has continued uninterrupted for 1300 years, or in the city of Inuyama, Aichi. In Guilin, Guangxi, cormorants are famous for fishing on the shallow Li River. In Gifu, the Japanese cormorant (P. capillatus) is used; Chinese fishermen often employ great cormorants (P. carbo).[34] In Europe, a similar practice was also used on Doiran Lake in the region of Macedonia.[35]

In a common technique, a snare is tied near the base of the bird's throat, which allows the bird only to swallow small fish. When the bird captures and tries to swallow a large fish, the fish is caught in the bird's throat. When the bird returns to the fisherman's raft, the fisherman helps the bird to remove the fish from its throat. The method is not as common today, since more efficient methods of catching fish have been developed, but is still practised as a cultural tradition.[34][33]

In folklore, literature, and art

Cormorants feature in heraldry and medieval ornamentation, usually in their "wing-drying" pose, which was seen as representing the Christian cross, and symbolizing nobility and sacrifice. For John Milton in Paradise Lost, the cormorant symbolizes greed: perched atop the Tree of Life, Satan took the form of a cormorant as he spied on Adam and Eve during his first intrusion into Eden.[36]

In some Scandinavian areas, they are considered good omen; in particular, in Norwegian tradition spirits of those lost at sea come to visit their loved ones disguised as cormorants.[36] For example, the Norwegian municipalities of Røst, Loppa and Skjervøy have cormorants in their coat of arms. The symbolic liver bird of Liverpool is commonly thought to be a cross between an eagle and a cormorant.

In Homer's epic poem The Odyssey, Odysseus (Ulysses) is saved by a compassionate sea nymph who takes the form of a cormorant.

In 1853, a woman wearing a dress made of cormorant feathers was found on San Nicolas Island, off the southern coast of California. She had sewn the feather dress together using whale sinews. She is known as the Lone Woman of San Nicolas and was later baptised "Juana Maria" (her original name is lost). The woman had lived alone on the island for 18 years before being rescued. When removed from San Nicolas, she brought with her a green cormorant dress she made; this dress is reported to have been removed to the Vatican.

The bird has inspired numerous writers, including Amy Clampitt, who wrote a poem called "The Cormorant in its Element". The species she described may have been the pelagic cormorant, which is the only species in the temperate U.S. with the "slim head ... vermilion-strapped" and "big black feet" that she mentions.

A cormorant representing Blanche Ingram appears in the first of the fictional paintings by Jane in Charlotte Brontë's novel Jane Eyre.

In the Sherlock Holmes story "The Adventure of the Veiled Lodger", Dr. Watson warns that if there are further attempts to get at and destroy his private notes regarding his time with Holmes, "the whole story concerning the politician, the lighthouse, and the trained cormorant will be given to the public. There is at least one reader who will understand."

A cormorant is humorously mentioned as having had linseed oil rubbed into it by a wayward pupil during the "Growth and Learning" segment of the 1983 Monty Python movie Monty Python's The Meaning of Life.

The cormorant served as the hood ornament for the Packard automobile brand.[37]

Cormorants (and books about them written by a fictional ornithologist) are a recurring fascination of the protagonist in Jesse Ball's 2018 novel Census.

The Pokémon Cramorant, featured in the 8th generation of the video game series may take its name and design from a cormorant.

The cormorant was chosen as the emblem for the Ministry of Defence Joint Services Command and Staff College at Shrivenham. A bird famed for flight, sea fishing and land nesting was felt to be particularly appropriate for a college that unified leadership training and development for the Army, Navy and Royal Air Force.

See also

References

- "Cormorants and shags". RSPB. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- Elliott, KH; Ricklefs, RE; Gaston, AJ; Hatch, SA; Speakman, JR; Davoren, GK (2013). "High flight costs and low dive costs support the biomechanical hypothesis for flightlessness in penguins". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (23): 9380–9384. doi:10.1073/pnas.1304838110. PMC 3677478. PMID 23690614.

- Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 301. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- "www.nwdiveclub.com/download/file.php?id=22712&mode=view". nwdiveclub.com.

- "Birds diving beyond 50ft down and going horizontally there?!". NWDiveClub.com. Northwest Dive Club.

- Cormorants Deep Sea Dive Caught on Camera. Wildlife Conservation Society. 2011-12-14.

- Cramp S, Simmons KEL (1977) Handbook of the Birds of the Western Palearctic Volume 1, Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-857358-8

- Rijke AM (1968). "The water repellency and feather structure of cormorants, Phalacrocoracidae". J. Exp. Biol. 48: 185–189.

- Marchant S. M.; Higgins, P. J. (1990). Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. Vol 1A. Oxford University Press.

- Hennemann, W. W., III (1984). "Spread-winged behaviour of double-crested and flightless cormorants Phalacrocorax auritus and P. harrisi: wing drying or thermoregulation?". Ibis. 126 (2): 230–239. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1984.tb08002.x.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Cook, Timothee R; Guillaume Leblanc (2007). "Why is wing-spreading behaviour absent in blue-eyed shags?" (PDF). Animal Behaviour. 74 (3): 649–652. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2006.11.024. S2CID 53201673.

- Curry-Lindahl, K (1970). "Spread-wing postures in Pelecaniformes and Ciconiiformes" (PDF). Auk. 87 (2): 371–372. doi:10.2307/4083936. JSTOR 4083936.

- Sellers, R. M. (1995). "Wing-spreading behavior of the cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo" (PDF). Ardea. 83: 27–36.

- Nelson, J. Bryan (2005). Pelicans, Cormorants and Their Relatives: Pelecanidae, Sulidae, Phalacrocoracidae, Anhingidae, Fregatidae, Phaethontidae. Oxford University Press. pp. 162–163. ISBN 0-19-857727-3.

- Bernstein, N. P; S J Maxson (1982). "Absence of Wing-spreading Behavior in the Antarctic Blue-eyed Shag (Phalacrocorax Atriceps Bransfieldensis)" (PDF). The Auk. 99 (3): 588–589.

- Kennedy et al. (2000), Mayr (2005)

- See Siegel-Causey (1988), Orta (1992) and Kennedy et al. (2000) for a review of classification schemes.

- Orta (1992)

- IUCN (2007)

- Yarrell, William (1828). "On the xiphoid bone and its muscles in the Corvorant (Pelecanus carbo)". The Zoological Journal. 4: 234–237.

- Garrod, A. H. (2009). "1. Notes on the Anatomy of Plotus anhinga". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 44: 335–345. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1876.tb02572.x.

- Burger, A E (2015). "Functional Anatomy of the Feeding Apparatus of Four South African Cormorants". Zoologica Africana. 13: 81–102. doi:10.1080/00445096.1978.11447608.

- Shufeldt, R.W. (1915). "Comparative osteology of Harris's Flightless Cormorant (Nannopterum harrisi)". Emu. 15 (2): 86–114. doi:10.1071/MU915086.

- van Tets (1976), Siegel-Causey (1988)

- Kennedy et al. (2000)

- Gill, F.; Donsker, D.; Rasmussen, P. (July 2020). "IOC World Bird List (v 10.2)". Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- Kurochkin (1995)

- Hope (2002)

- Hope (2002) and see Hesperornithes

- A proximal ulna, Specimen PB 311, Pierce Brodkorb collection. Initially assigned to P. idahensis. However, it is far too large, being from a very big species possibly larger than a great cormorant: Murray (1970)

- At least part of a coracoid is known. Does not appear to belong to the true cormorants. May have been closer in habitus to North Pacific shags, but not closely related to these: Howard (1932).

- Cracraft (1971)

- Richard J. King (1 October 2013). The Devil's Cormorant: A Natural History. University of New Hampshire Press. pp. 9–. ISBN 978-1-61168-225-0.

- "Cormorant Fishing "UKAI"". May 2001. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- "About Dojran lake". Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- Arin Murphy-Hiscock (18 January 2012). Birds - A Spiritual Field Guide: Explore the Symbology and Significance of These Divine Winged Messengers. Adams Media. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-1-4405-2688-6.

- John Gunnell (January 2004). Standard Guide to 1950s American Cars. Krause Publications. p. 192. ISBN 0-87349-868-2.

Sources

- Benson, Elizabeth (1972): The Mochica: A Culture of Peru. Praeger Press, New York.

- Berrin, Katherine & Larco Museum (1997) The Spirit of Ancient Peru: Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. Thames and Hudson, New York.

- Cracraft, Joel (1971). "Systematics and evolution of the Gruiformes (Class Aves). 2. Additional comments on the Bathornithidae, with descriptions of new species" (PDF). American Museum Novitates. 2449: 1–14.

- Dorst, J. & Mougin, J.L. (1979): Family Phalacrocoracidae. In: Mayr, Ernst & Cottrell, G.W. (eds.): Check-List of the Birds of the World Vol. 1, 2nd ed. (Struthioniformes, Tinamiformes, Procellariiformes, Sphenisciformes, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Pelecaniformes, Ciconiiformes, Phoenicopteriformes, Falconiformes, Anseriformes): 163–179. Museum of Comparative Zoology, Cambridge.

- Hope, Sylvia (2002): The Mesozoic radiation of Neornithes. In: Chiappe, Luis M. & Witmer, Lawrence M. (eds.): Mesozoic Birds: Above the Heads of Dinosaurs: 339–388. ISBN 0-520-20094-2

- Howard, Hildegarde (1932). "A New Species of Cormorant from Pliocene Deposits near Santa Barbara, California" (PDF). Condor. 34 (3): 118–120. doi:10.2307/1363540. JSTOR 1363540.

- IUCN (2007): 2007 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN, Gland.

- Kennedy, M.; Gray, R.D.; Spencer H.G. (2000). "The Phylogenetic Relationships of the Shags and Cormorants: Can Sequence Data Resolve a Disagreement between Behavior and Morphology?" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 17 (3): 345–359. doi:10.1006/mpev.2000.0840. PMID 11133189. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-04-18.

- Kurochkin, Evgeny N. (1995). "Synopsis of Mesozoic birds and early evolution of Class Aves" (PDF). Archaeopteryx. 13: 47–66. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-27.

- Mayr, Gerald (2005). "Tertiary plotopterids (Aves, Plotopteridae) and a novel hypothesis on the phylogenetic relationships of penguins (Spheniscidae)" (PDF). Journal of Zoological Systematics. 43 (1): 67–71. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.2004.00291.x.

- Murray, Bertram G., Jr. (1970). "A Redescription of Two Pliocene Cormorants" (PDF). Condor. 72 (3): 293–298. doi:10.2307/1366006. JSTOR 1366006.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Orta, Jaume (1992): Family Phalacrocoracidae. In: del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew & Sargatal, Jordi (eds.): Handbook of Birds of the World, Volume 1 (Ostrich to Ducks): 326–353, plates 22–23. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. ISBN 84-87334-10-5

- Robertson, Connie (1998): Book of Humorous Quotations. Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 1-85326-759-7

- Siegel-Causey, Douglas (1988). "Phylogeny of the Phalacrocoracidae" (PDF). Condor. 90 (4): 885–905. doi:10.2307/1368846. JSTOR 1368846.

- Thevet, F. André (1558): About birds of Ascension Island. In: Les singularitez de la France Antarctique, autrement nommee Amerique, & de plusieurs terres & isles decouvertes de nostre temps: 39–40. Maurice de la Porte heirs, Paris.

- van Tets, G. F. (1976): Australasia and the origin of shags and cormorants, Phalacrocoracidae. Proceedings of the XVI International Ornithological Congress: 121–124.

Further reading

- Kennedy, M.; Spencer, H.G. (2014). "Classification of the cormorants of the world". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 79: 249–257. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2014.06.020. PMID 24994028.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to |

| Look up cormorant in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Cormorant videos on the Internet Bird Collection

- "Recovery plan for Chatham Island shag and Pitt Island shag 2001–2011" (PDF). Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand. 2001. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- First video of cormorant deep sea dive, by the Wildlife Conservation Society and the National Research Council of Argentina. WCS press release, 2012-07-31

_in_Hyderabad_W_IMG_8389.jpg.webp)