Cot–caught merger

The cot–caught merger or LOT–THOUGHT merger, formally known in linguistics as the low back merger, is a sound change present in some dialects of English where speakers do not distinguish the vowel sounds in "cot" and "caught". "Cot" and "caught" (along with "bot" and "bought", "pond" and "pawned", etc.) is an example of a minimal pair that is lost as a result of this sound change. The English phonemes involved in the cot-caught merger, the low back vowels, are typically represented in the International Phonetic Alphabet as /ɒ/ and /ɔ/, respectively. The merger is typical of most Canadian and Scottish English dialects as well as many Irish and American English dialects.

An additional vowel merger, the father-bother merger, which spread through North America in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, has resulted today in a three-way merger in which most Canadian and many American accents have no vowel difference in words like "palm" /ɑ/, "lot" /ɒ/, and "thought" /ɔ/.

Overview

| IPA: Vowels | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vowels beside dots are: unrounded • rounded |

The shift causes the vowel sound in words like cot, nod and stock and the vowel sound in words like caught, gnawed and stalk to merge into a single phoneme; therefore the pairs cot and caught, stock and stalk, nod and gnawed become perfect homophones, and shock and talk, for example, become perfect rhymes. The cot–caught merger is completed in the following dialects:

- Some dialects within the British Isles:

- All Scottish English accents, towards [ɔ] (

listen) (without the father–bother merger)[1]

listen) (without the father–bother merger)[1] - Irish English broad and traditional accents, including:

- All Scottish English accents, towards [ɔ] (

- Many North American English accents:

- Several accents of U.S. English, including:[3]

- Pittsburgh English, towards [ɒ~ɔ] (with the father–bother merger)[4]

- All New England English towards [ɑ~ɒ] (in Boston and Eastern New England, particularly towards [ɒ] (

listen)), except in Rhode Island and southern Connecticut[3]

listen)), except in Rhode Island and southern Connecticut[3] - All Western American English (with the father–bother merger)[3]

- Upper Midwestern English, Cajun English, and Chicano English towards [ä] (

listen).[5]

listen).[5] - Younger U.S. English, in general, increasingly favors the merger, regardless of region

- Nearly all Canadian English, including:[6]

- Standard Canadian English towards [ɒ] (

listen) (with the father–bother merger)

listen) (with the father–bother merger) - Maritimer and Newfoundland English, towards [ɑ~ä] (with the father–bother merger)

- Standard Canadian English towards [ɒ] (

- Several accents of U.S. English, including:[3]

- Some Singaporean English (without the father–bother merger)[7]

| /ɑ/ or /ɒ/ (written a, o, ol) | /ɔ/ (written au, aw, al, ough) | IPA (using ⟨ɒ⟩ for the merged vowel) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| bobble | bauble | ˈbɒbəl | |

| bock | balk | ˈbɒk | |

| body | bawdy | ˈbɒdi | |

| bon | bawn | ˈbɒn | |

| bot | bought | ˈbɒt | |

| box | balks | ˈbɒks | |

| chock | chalk | ˈtʃɒk | |

| clod | Claude | ˈklɒd | |

| clod | clawed | ˈklɒd | |

| cock | caulk | ˈkɒk | |

| cod | cawed | ˈkɒd | |

| coddle | caudle | ˈkɒdəl | |

| collar | caller | ˈkɒlə(r) | |

| cot | caught | ˈkɒt | |

| doddle | dawdle | ˈdɒdəl | |

| don | dawn, Dawn | ˈdɒn | |

| dotter | daughter | ˈdɒtə(r) | |

| fond | fawned | ˈfɒnd | |

| fox | Fawkes | ˈfɒks | |

| frot | fraught | ˈfrɒt | |

| god | gaud | ˈɡɒd | |

| hock | hawk | ˈhɒk | |

| holler | hauler | ˈhɒlə(r) | |

| hottie | haughty | ˈhɒti | |

| hough | hawk | ˈhɒk | |

| knot | naught | ˈnɒt | |

| knot | nought | ˈnɒt | |

| knotty | naughty | ˈnɒti | |

| mod | Maud, Maude | ˈmɒd | |

| Moll | mall | ˈmɒl | |

| Moll | maul | ˈmɒl | |

| nod | gnawed | ˈnɒd | |

| not | naught | ˈnɒt | |

| not | nought | ˈnɒt | |

| odd | awed | ˈɒd | |

| offal | awful | ˈɒfəl | Already homophonous in dialects with the lot-cloth split. |

| Otto | auto | ˈɒtoʊ | |

| Oz | awes | ˈɒz | |

| pod | pawed | ˈpɒd | |

| pol | Paul | ˈpɒl | |

| pol | pall | ˈpɒl | |

| pol | pawl | ˈpɒl | |

| Poll | Paul | ˈpɒl | |

| Poll | pall | ˈpɒl | |

| Poll | pawl | ˈpɒl | |

| Polly | Paulie, Pauly | ˈpɒli | |

| poly | Paulie, Pauly | ˈpɒli | |

| pond | pawned | ˈpɒnd | |

| popper | pauper | ˈpɒpə(r) | |

| poz | pause | ˈpɒz | |

| poz | paws | ˈpɒz | |

| rot | wrought | ˈrɒt | |

| slotter | slaughter | ˈslɒtə(r) | |

| sod | sawed | ˈsɒd | |

| Sol | Saul | ˈsɒl | |

| squalor | squaller | ˈskwɒlə(r) | |

| stock | stalk | ˈstɒk | |

| tock | talk | ˈtɒk | |

| tot | taught | ˈtɒt | |

| tot | taut | ˈtɒt | |

| tox | talks | ˈtɒks | |

| von | Vaughan | ˈvɒn | |

| wok | walk | ˈwɒk | |

| yon | yawn | ˈjɒn |

North American English

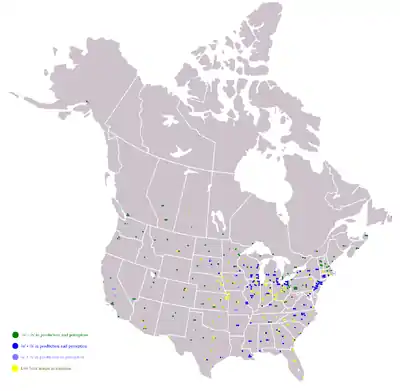

Nowhere is the shift more complex than in North American English. The presence of the merger and its absence are both found in many different regions of the North American continent, where it has been studied in greatest depth, and in both urban and rural environments. The symbols traditionally used to transcribe the vowels in the words cot and caught as spoken in American English are ⟨ɑ⟩ and ⟨ɔ⟩, respectively, although their precise phonetic values may vary, as does the phonetic value of the merged vowel in the regions where the merger occurs.

Even without taking into account the mobility of the American population, the distribution of the merger is still complex; there are pockets of speakers with the merger in areas that lack it, and vice versa. There are areas where the merger has only partially occurred, or is in a state of transition. For example, based on research directed by William Labov (using telephone surveys) in the 1990s, younger speakers in Kansas, Nebraska, and the Dakotas exhibited the merger while speakers older than 40 typically did not.[9][10] The 2003 Harvard Dialect Survey, in which subjects did not necessarily grow up in the place they identified as the source of their dialect features, indicates that there are speakers of both merging and contrast-preserving accents throughout the country, though the basic isoglosses are almost identical to those revealed by Labov's 1996 telephone survey. Both surveys indicate that, as of the 1990s, approximately 60% of American English speakers preserved the contrast, while approximately 40% merged the phonemes. Further complicating matters are speakers who merge the phonemes in some contexts but not others, or merge them when the words are spoken unstressed or casually but not when they're stressed.

Speakers with the merger in northeastern New England still maintain a phonemic distinction between a fronted and unrounded /ɑ/ (phonetically [ä]) and a back and usually rounded /ɔ/ (phonetically [ɒ]), because in northeastern New England (unlike in Canada and the Western United States), the cot–caught merger occurred without the father–bother merger. Thus, although northeastern New Englanders pronounce both cot and caught as [kɒt], they pronounce cart as [kät].

Labov et al. also reveal that, for about 15% of respondents, a specific /ɑ/–/ɔ/ merger before /n/ but not before /t/ (or other consonants) is in effect, so that Don and dawn are homophonous, but cot and caught are not. In this case, a distinct vowel shift (which overlaps with the cot–caught merger for all speakers who have indeed completed the cot–caught merger) is taking place, identified as the Don–dawn merger.[11]

Resistance

According to Labov, Ash, and Boberg,[12] the merger in North America is most strongly resisted in three regions:

- The "South", somewhat excluding Texas and Florida

- The "Inland North", encompassing the eastern and central Great Lakes region (on the U.S. side of the border)

- The "Northeast Corridor" along the Atlantic coast, ranging from Baltimore to Philadelphia to New York City to Providence. Boston and further northern New England do not display these traits.

In the three American regions above, sociolinguists have studied three phonetic shifts that can explain their resistance to the merger. The first is the fronting of /ɑ/ found in the Inland North; speakers advance the LOT vowel /ɑ/ as far as the cardinal [a] (the open front unrounded vowel), thus allowing the THOUGHT vowel /ɔ/ to lower into the phonetic environment of [ɑ] without any merger taking place.[13] The second situation is the raising of the THOUGHT vowel /ɔ/ found in the New York City, Philadelphia and Baltimore accents, in which the vowel is raised and diphthongized to [ɔə⁓oə], or, less commonly, [ʊə], thus keeping that vowel notably distinct from the LOT vowel /ɑ/.[13] The third situation occurs in the South, in which vowel breaking results in /ɔ/ being pronounced as upgliding [ɒʊ], keeping it distinct from /ɑ/.[13] None of these three phonetic shifts, however, is certain to preserve the contrast for all speakers in these regions. Many speakers in all three regions, particularly younger ones, are beginning to exhibit the merger despite the fact that each region's phonetics should theoretically block it.

African-American Vernacular English varieties have traditionally resisted the cot-caught merger, with LOT pronounced [ä] and THOUGHT traditionally pronounced [ɒɔ], though now often [ɒ~ɔə]. Early 2000s research has shown that this resistance may continue to be reinforced by the fronting of LOT, linked through a chain shift of vowels to the raising of the TRAP, DRESS, and perhaps KIT vowels. This chain shift is called the "African American Shift".[14] However there is evidence of AAVE speakers speaking with the cot-caught merger in Pittsburgh[15] and Charleston, South Carolina.[16]

Origin

The merger, or its initial conditions, began specifically in eastern New England and western Pennsylvania, from which it entered Atlantic and mainland Canada, respectively. The merger is in evidence as early as the 1830s in both regions of Canada. Fifty years later, the merger was "was already more established in Canada" than in its U.S. places of origin.[17] In Canadian English, the westward spread was completed more quickly than in English of the United States.

Two traditional theories of the merger's origins have been longstanding in linguistics: one group of scholars argues for an independent North American development, while others argue for contact-induced language change via Scots-Irish or Scottish immigrants to North America. In fact, both theories may be true but for different regions. The merger's appearance in western Pennsylvania is better explained as an effect of Scots-Irish settlement,[18] but in eastern New England,[19] and perhaps the American West,[20] as an internal structural development. Canadian linguist Charles Boberg considers the issue unresolved (Boberg 2010: 199?).[21] A third theory has been used to explain the merger's appearance specifically in northeastern Pennsylvania: an influx of Polish- and other Slavic-language speakers whose learner English failed to maintain the distinction.[22]

England

In London's Cockney accent, a cot–caught merger is possible only in rapid speech. The THOUGHT vowel has two phonemically distinct variants: closer /oː/ (phonetically [oː ~ oʊ ~ ɔo]) and more open /ɔə/ (phonetically [ɔə ~ ɔwə ~ ɔː]). The more open variant is sometimes neutralized in rapid speech with the LOT vowel /ɒ/ (phonetically [ɒ ~ ɔ]) in utterances such as [sˈfɔðɛn] (phonemically /ɑɪ wəz ˈfɔə ðen/) for I was four then. Otherwise /ɔə/ is still readily distinguished from /ɒ/ by length.[23]

Scotland

Outside North America, another dialect featuring the merger is Scottish English. Like in New England English, the cot–caught merger occurred without the father–bother merger. Therefore, speakers still retain the distinction between /a/ and /ɔ/.

References

- Wells 1982, p. ?

- Heggarty, Paul; et al., eds. (2013). "Accents of English from Around the World". University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), pp. 60-1

- Gagnon, C. L. (1999). Language attitudes in Pittsburgh: 'Pittsburghese' vs. standard English. Master's thesis. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh.

- Dubois, Sylvia; Horvath, Barbara (2004). "Cajun Vernacular English: phonology". In Kortmann, Bernd; Schneider, Edgar W. (eds.). A Handbook of Varieties of English: A Multimedia Reference Tool. New York: Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 409–10.

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 218

- "Singapore English" (PDF). Videoweb.nie.edu.sg. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 122

- Gordon (2005)

- "Map 1". Ling.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 217

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), pp. 56-65

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), chpt. 11

- Thomas, Erik. (2007). "Phonological and phonetic characteristics of AAVE". Language and Linguistics Compass. 1. 450 - 475. 10.1111/j.1749-818X.2007.00029.x. p. 464.

- Eberhardt (2008).

- Baranowski (2013).

- Dollinger, Stefan (2010). "Written sources of Canadian English: phonetic reconstruction and the low-back vowel merger". Academia.edu. Retrieved 2016-03-19.

- Evanini, Keelan (2009). "The permeability of dialect boundaries: A case study of the region surrounding Erie, Pennsylvania". University of Pennylvania; dissertations available from ProQuest. AAI3405374. pp. 254-255.

- Johnson, Daniel Ezra (2010). "LOW VOWELS OF NEW ENGLAND: HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT". Publication of the American Dialect Society 95 (1): 13–41. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/-95-1-13. p. 40.

- Grama, James; Kennedy, Robert (2019). "2. Dimensions of Variance and Contrast in the Low Back Merger and the Low-Back-Merger Shift". The Publication of the American Dialect Society. 104, p. 47.

- Boberg, Charles (2010). The English language in Canada. Cambridge: Cambridge. pp. 199?.

- Herold, Ruth. (1990). "Mechanisms of merger: The implementation and distribution of the low back merger in eastern Pennsylvania". Doctoral dissertation, University of Pennsylvania.

- Wells 1982, pp. 305, 310, 318–319

Bibliography

- Barber, Charles Laurence (1997). Early modern English (second ed.). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-0835-4.

- Gordon, Matthew J. (2005), "The Midwest Accent", American Varieties, PBS, retrieved August 29, 2010

- Labov, William; Ash, Sharon; Boberg, Charles (2006). The Atlas of North American English: Phonetics, Phonology, and Sound Change: a Multimedia Reference Tool. Berlin ; New York: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-016746-8.

- Wells, John C. (1982), Accents of English, Volume 2: The British Isles (pp. i–xx, 279–466), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-52128540-2

External links

- Map of the cot–caught merger from the 2003 Harvard Dialect Survey

- Map of the cot–caught merger from Labov's 1996 telephone survey

- Description of the cot–caught merger in the Phonological Atlas

- Map of the cot–caught merger before /n/ and /t/

- Chapter 13 of the Atlas of North American English, which discusses the "short-o" configuration of various American accents