Standard Canadian English

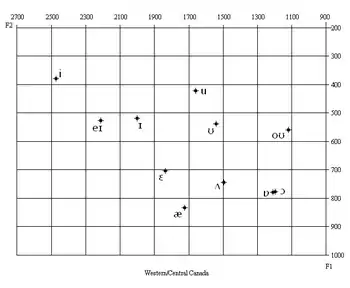

Standard Canadian English is the greatly homogeneous variety of Canadian English spoken particularly all across central and western Canada, as well as throughout Canada among urban middle-class speakers from English-speaking families,[1] excluding the regional dialects of Atlantic Canadian English. English mostly has a uniform phonology and very little diversity of dialects in Canada compared with the neighbouring English of the United States.[2] The Standard Canadian English dialect region is defined by the cot–caught merger to [ɒ] (![]() listen) and an accompanying chain shift of vowel sounds, called the Canadian Shift. A subset of this dialect geographically at its central core, excluding British Columbia to the west and everything east of Montreal, has been called Inland Canadian English, and is further defined by both of the phenomena known as Canadian raising (also found in British Columbia and Ontario),[3] the production of /oʊ/[lower-alpha 1] and /aʊ/ with back starting points in the mouth, and the production of /eɪ/ with a front starting point and very little glide,[4] almost [e] in the Prairie provinces.[5]

listen) and an accompanying chain shift of vowel sounds, called the Canadian Shift. A subset of this dialect geographically at its central core, excluding British Columbia to the west and everything east of Montreal, has been called Inland Canadian English, and is further defined by both of the phenomena known as Canadian raising (also found in British Columbia and Ontario),[3] the production of /oʊ/[lower-alpha 1] and /aʊ/ with back starting points in the mouth, and the production of /eɪ/ with a front starting point and very little glide,[4] almost [e] in the Prairie provinces.[5]

Phonetics and phonology

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lax | tense | lax | tense | |||

| Close | ɪ | i | ʊ | u | ||

| Mid | ɛ | eɪ | ə | ʌ | oʊ | |

| Open | æ | ɒ | ||||

| Diphthongs | aɪ ɔɪ aʊ | |||||

The phonemes /oʊ/ (as in boat) and /eɪ/ (as in bait) have qualities much closer to pure vowel (monophthongs) in some speakers, especially in the inland (Prairies Provinces) region.

Almost all Canadians have the cot–caught merger, which also occurs primarily in the Western U.S., but often elsewhere in the U.S., especially recently. Speakers do not distinguish the vowels in cot and caught which merger as either [ɒ] (more common in Western and Maritime Canada) or [ɑ] (more common in central and eastern mainland Canada, where it might even be fronted). Speakers with this merger produce these vowels identically, and often fail to hear the difference when speakers who preserve the distinction (for example, speakers of General American and Inland Northern American English) pronounce these vowels. This merger has existed in Canada for several generations.[6]

The standard pronunciation of /ɒr/ (as in start) is [ɑɹ], as in General American, or perhaps somewhat fronted as [ɑ̈ɹ]. As with Canadian raising, the advancement of the raised nucleus can be a regional indicator. A striking feature of Atlantic Canadian speech (the Maritimes and Newfoundland) is a nucleus that approaches the front region of the vowel space, accompanied by strong rhoticity, ranging from [ɜɹ] to [ɐɹ].

The words origin, Florida, horrible, quarrel, warren, as well as tomorrow, sorry, sorrow, etc. all generally use the sound sequence of FORCE rather than START. The latter set of words often distinguishes Canadian pronunciation from U.S. pronunciation. In Standard Canadian English, there is no distinction between the vowels in horse and hoarse.

This merger creates a hole in the short vowel sub-system[7] and triggers a sound change known as the Canadian Shift, which involves the front lax vowels /æ, ɛ, ɪ/. The /æ/ of bat is lowered and retracted in the direction of [a] (except in some environments, see below). Indeed, /æ/ is further back in this variety than almost all other North American dialects;[8] the retraction of /æ/ was independently observed in Vancouver[9] and is more advanced for Ontarians and women than for people from the Prairies or Atlantic Canada and men.[10] Then, /ɛ/ and /ɪ/ may be lowered (in the direction of [æ] and [ɛ]) and/or retracted; studies actually disagree on the trajectory of the shift.[11] For example, Labov and others (2006) noted a backward and downward movement of /ɛ/ in apparent time in all of Canada except the Atlantic Provinces, but no movement of /ɪ/ was detected.

Therefore, in Canadian English, the short-a of trap or bath and the broad ah quality of spa or lot are shifted in opposite directions to that of the Northern Cities shift, found across the border in the Inland Northern U.S., which is causing these two dialects to diverge: in fact, the Canadian short-a is very similar in quality to Inland Northern spa or lot; for example, the production [map] would be recognized as map in Canada, but mop in the Inland North dialect of the U.S.

A notable exception to the merger occurs, in which some speakers over the age of 60, especially in rural areas in the Prairies, may not exhibit the merger.

Perhaps the most recognizable feature of Canadian English is "Canadian raising," which is found most prominently throughout central and west-central Canada, as well as in parts of the Atlantic Provinces.[2] For the beginning points of the diphthongs (gliding vowels) /aɪ/ (as in the words height and mice) and /aʊ/ (as in shout and house), the tongue is often more "raised" in the mouth when these diphthongs come before voiceless consonants, namely /p/, /t/, /k/, /s/, /ʃ/ and /f/, in comparison with other varieties of English.

Before voiceless consonants, /aɪ/ becomes [ʌɪ~ɜɪ~ɐɪ]. One of the few phonetic variables that divides Canadians regionally is the articulation of the raised allophone of this as well as of /aʊ/; in Ontario, it tends to have a mid-central or even mid-front articulation, sometimes approaching [ɛʊ], while in the West and Maritimes a more retracted sound is heard, closer to [ʌʊ].[12] Among some speakers in the Prairies and in Nova Scotia, the retraction is strong enough to cause some tokens of raised /aʊ/ to merge with /oʊ/, so that couch merges with coach, meaning the two sound the same (/koʊtʃ/), and about sounds like a boat; this is often inaccurately represented as sounding like "a boot" for comic effect in American popular culture.

In General American, out is typically [äʊt] (![]() listen), but, with slight Canadian raising, it may sound more like [ɐʊt] (

listen), but, with slight Canadian raising, it may sound more like [ɐʊt] (![]() listen), or, with the strong Canadian raising of the Prairies and Nova Scotia, more like IPA: [ʌʊt]. Due to Canadian raising, words like height and hide have two different vowel qualities; also, for example, house as a noun (I saw a house) and house as a verb (Where will you house them tonight?) have two different vowel qualities: potentially, [hɐʊs] versus [haʊz].

listen), or, with the strong Canadian raising of the Prairies and Nova Scotia, more like IPA: [ʌʊt]. Due to Canadian raising, words like height and hide have two different vowel qualities; also, for example, house as a noun (I saw a house) and house as a verb (Where will you house them tonight?) have two different vowel qualities: potentially, [hɐʊs] versus [haʊz].

Especially in parts of the Atlantic provinces, some Canadians do not possess the phenomenon of Canadian raising. On the other hand, certain non-Canadian accents demonstrate Canadian raising. In the U.S., this feature can be found in areas near the border and thus in the Upper Midwest, Pacific Northwest, and northeastern New England (e.g. Boston) dialects, though it is much less common than in Canada. The raising of /aɪ/ alone is actually increasing throughout the U.S. and, unlike raising of /aʊ/, is generally not perceived as unusual by people who do not have the raising.

Because of Canadian raising, many speakers are able to distinguish between words such as writer and rider –which can otherwise be impossible, since North American dialects typically turn both intervocalic /t/ and /d/ into an alveolar flap. Thus writer and rider are distinguished solely by their vowel characteristics as determined by Canadian raising: thus, a split between rider as [ˈɹäɪɾɚ] and writer possibly as [ˈɹʌɪɾɚ] (![]() listen).

listen).

When not in a raised position (before voiceless consonants), /aʊ/ is fronted to [aʊ~æʊ] before nasals, and low-central [äʊ] elsewhere.

Unlike in many American English dialects, /æ/ remains a low-front vowel in most environments in Canadian English. Raising along the front periphery of the vowel space is restricted to two environments – before nasal and voiced velar consonants – and varies regionally even in these. Ontario and Maritime Canadian English commonly show some raising before nasals, though not as extreme as in many U.S. varieties. Much less raising is heard on the Prairies, and some ethnic groups in Montreal show no pre-nasal raising at all. On the other hand, some Prairie speech exhibits raising of /æ/ before voiced velars (/ɡ/ and /ŋ/), with an up-glide rather than an in-glide, so that bag can almost rhyme with vague.[13] For most Canadian speakers, /ɛ/ is also realized higher as [e] before /ɡ/.

| Following consonant |

Example words[15] |

New York City,[15] New Orleans[16] |

Baltimore, Philadel- phia[15][17] |

General American, New England, Western US |

Midland US, Pittsburgh |

Southern US |

Canada, Northern Mountain US |

Minnesota, Wisconsin |

Great Lakes US |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-prevocalic /m, n/ |

fan, lamb, stand | [ɛə][18][upper-alpha 1][upper-alpha 2] | [ɛə][18] | [ɛə] | [ɛə~ɛjə][20] | [ɛə][21] | [ɛə][22][18] | ||

| Prevocalic /m, n/ |

animal, planet, Spanish |

[æ] | |||||||

| /ŋ/[23] | frank, language | [ɛː~eɪ][24] | [æ][23] | [æ~æɛə][20] | [ɛː~ɛj][21] | [eː~ej][25] | |||

| Non-prevocalic /ɡ/ |

bag, drag | [ɛə][upper-alpha 1] | [æ][upper-alpha 3] | [æ][18] | |||||

| Prevocalic /ɡ/ | dragon, magazine | [æ] | |||||||

| Non-prevocalic /b, d, ʃ/ |

grab, flash, sad | [ɛə][upper-alpha 1] | [æ][26] | [ɛə][26] | |||||

| Non-prevocalic /f, θ, s/ |

ask, bath, half, glass |

[ɛə][upper-alpha 1] | |||||||

| Otherwise | as, back, happy, locality |

[æ][upper-alpha 4] | |||||||

| |||||||||

Phonemic incidence

Although Canadian English phonology is part of the greater North American sound system, and therefore similar to U.S. English phonology, the pronunciation of particular words may have British influence, while other pronunciations are uniquely Canadian. According to the Cambridge History of the English Language, [w]hat perhaps most characterizes Canadian speakers, however, is their use of several possible variant pronunciations for the same word, sometimes even in the same sentence.[29]

- The name of the letter Z is normally the Anglo-European (and French) zed; the American zee is less common in Canada, and it is often stigmatized, though the latter is not uncommon, especially among younger Canadians.[30][31]

- Lieutenant was historically pronounced as the British /lɛfˈtɛnənt/ rather than the American /luˈtɛnənt/;[32] although older speakers of Canadian English, and official usage in military and government contexts, typically still follow the older practice, most younger speakers and many middle-aged speakers have shifted to the American pronunciation. Some middle-aged speakers don't even remember the existence of the older pronunciation, even when specifically asked whether they can think of another pronunciation. Only 14 to 19% of 14-year-olds used the traditional pronunciation in a survey in 1972, and they are meanwhile (at the beginning of 2017) at least 57 years old.[32]

- In the words adult and composite – the emphasis is usually on the first syllable (/ˈædʌlt/ ~ /ˈædəlt/, /ˈkɒmpəzət/), as in Britain.

- Canadians often side with the British on the pronunciation of lever /ˈlivər/, and several other words; been is pronounced by many speakers as /bin/ rather than /bɪn/; as in Southern England, either and neither are more commonly /ˈaɪðər/ and /ˈnaɪðər/, respectively.

- Furthermore, in accordance with British traditions, schedule can sometimes be /ˈʃɛdʒul/; process, progress, and project are occasionally pronounced /ˈproʊsɛs/, /ˈproʊɡrɛs/, and /ˈproʊdʒɛkt/, respectively; harass and harassment are sometimes pronounced /ˈhærəs/ and /ˈhærəsmənt/, respectively,[33] while leisure is rarely /ˈlɛʒər/.

- Shone is pronounced /ʃɒn/, rather than /ʃoʊn/.

- Again and against are often pronounced /əˈɡeɪn, əˈɡeɪnst/ rather than /əˈɡɛn, əˈɡɛnst/.

- The stressed vowel of words such as borrow, sorry or tomorrow is [ɔ], like the vowel of FORCE rather than of START.[34]

- Words like semi, anti, and multi tend to be pronounced /ˈsɛmi/, /ˈænti/, and /ˈmʌlti/ rather than /ˈsɛmaɪ/, /ˈæntaɪ/, and /ˈmʌltaɪ/.

- Loanwords that have a low central vowel in their language of origin, such as llama, pasta, and pyjamas, as well as place names like Gaza and Vietnam, tend to have /æ/ rather than /ɒ/ (which includes the historical /ɑ/, /ɒ/ and /ɔ/ due to the father–bother and cot–caught mergers, see below); this also applies to older loans like drama or Apache. The word khaki is sometimes pronounced /ˈkɒki/ or /ˈkɒrki/, /ˈkɒrki/ is the preferred pronunciation of the Canadian Army during the Second World War.[35] The pronunciation of drama with /æ/ is in decline; studies found 83% of Canadians used /æ/ in 1956, 47% in 1999, and 10% in 2012.[36]

- Words of French origin, such as clique and niche, are pronounced with a high vowel, so /klik/ rather than /klɪk/, /niʃ/ rather than /nɪtʃ/.

- Pecan is usually /ˈpikæn/ or /piˈkæn/, as opposed to /pəˈkɒn/, more common in the US.[37]

- Syrup is commonly pronounced /ˈsɪrəp/ or /ˈsərəp/.

- The most common pronunciation of vase is /veɪz/.[38]

- The word Premier (the leader of a provincial or territorial government) is commonly pronounced /ˈprimjər/, with /ˈprɛmjɛr/ and /ˈprimjɛr/ being rare variants.

- Some Canadians pronounce predecessor as /ˈpridəsɛsər/ and asphalt as "ash-falt" /ˈæʃfɒlt/.[39]

- The word milk is realized as /mɛlk/ (to rhyme with elk) by some speakers, /mɪlk/ (to rhyme with ilk) by others.

- The word room is pronounced /rum/ or /rʊm/.

- Many Anglophone Montrealers pronounced French names with a Quebec accent: Trois-Rivières [tʁ̥wɑʁiˈvjæːʁ] or [tʁ̥wɑʁiˈvjaɛ̯ʁ]

Features shared with General American

Like most other North American English dialects, Canadian English is almost always spoken with a rhotic accent, meaning that the r sound is preserved in any environment and not "dropped" after vowels, as commonly done by, for example, speakers in central and southern England where it is only pronounced when preceding a vowel.

Like General American, Canadian English possesses a wide range of phonological mergers, many of which are not found in other major varieties of English: the Mary–marry–merry merger which makes word pairs like Barry/berry, Carrie/Kerry, hairy/Harry, perish/parish, etc. as well as trios like airable/errable/arable and Mary/merry/marry have identical pronunciations (however, a distinction between the marry and merry sets remains in Montreal);[2] the father–bother merger that makes lager/logger, con/Kahn, etc. sound identical; the very common horse–hoarse merger making pairs like for/four, horse/hoarse, morning/mourning, war/wore etc. perfect homophones (as in California English, the vowel is phonemicized as /oʊ/ due to the cot–caught merger: /foʊr/ etc.); and the prevalent wine–whine merger which produces homophone pairs like Wales/whales, wear/where, wine/whine etc. by, in most cases, eliminating /hw/ (ʍ), except in some older speakers.[6]

In addition to that, flapping of intervocalic /t/ and /d/ to alveolar tap [ɾ] before reduced vowels is ubiquitous, so the words ladder and latter, for example, are mostly or entirely pronounced the same. Therefore, the pronunciation of the word "British" /ˈbrɪtəʃ/ in Canada and the U.S. is most often [ˈbɹɪɾɪʃ], while in England it is commonly [ˈbɹɪtɪʃ] (![]() listen) or [ˈbɹɪʔɪʃ]. For some speakers, the merger is incomplete and 't' before a reduced vowel is sometimes not tapped following /eɪ/ or /ɪ/ when it represents underlying 't'; thus greater and grader, and unbitten and unbidden are distinguished.

listen) or [ˈbɹɪʔɪʃ]. For some speakers, the merger is incomplete and 't' before a reduced vowel is sometimes not tapped following /eɪ/ or /ɪ/ when it represents underlying 't'; thus greater and grader, and unbitten and unbidden are distinguished.

Many Canadian speakers have the typical American dropping of /j/ after alveolar consonants, so that new, duke, Tuesday, suit, resume, lute, for instance, are pronounced /nu/ (rather than /nju/), /duk/, /ˈtuzdeɪ/, /sut/, /rəˈzum/, /lut/. Traditionally, glide retention in these contexts has occasionally been held to be a shibboleth distinguishing Canadians from Americans. However, in a survey conducted in the Golden Horseshoe area of Southern Ontario in 1994, over 80% of respondents under the age of 40 pronounced student and news, for instance, without /j/.[40]

Notes

- The GOAT phoneme is here transcribed as a diphthong /oʊ/, in accordance with leading phonologists on Canadian English like William Labov,[lower-alpha 2] Charles Boberg,[lower-alpha 3] and others.[lower-alpha 4][lower-alpha 5]

- Labov, William; Ash, Sharon; Boberg, Charles (2006). The Atlas of North American English. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-016746-7.

- Boberg, 2008, p. 130.

- Bories-Sawala, Helga (2012). Qui parle canadien? diversité, identités et politiques linguistiques. Germany, Brockmeyer, pp. 10-11.

- Trudgill, Peter; Hannah, Jean (2013). "The pronunciation of Canadian English: General Canadian". International English: A Guide to the Varieties of Standard English. United Kingdom, Taylor & Francis, p. 53.

References

- Dollinger, Stefan (2012). "Varieties of English: Canadian English in real-time perspective." In English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook (HSK 34.2), Alexander Bergs & Laurel J. Brinton (eds), 1858-1880. Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 1859-1860.

- Labov, p. 222.

- Boberg, Charles (2008). "Regional Phonetic Differentiation in Standard Canadian English". Journal of English Linguistics, 36(2), 140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0075424208316648.

- Labov, 2006, p. 223-4.

- Boberg, 2008, p. 150.

- Labov p.218.

- Martinet, Andre 1955. Economie des changements phonetiques. Berne: Francke.

- Labov p. 219.

- Esling, John H. and Henry J. Warkentyne (1993). "Retracting of /æ/ in Vancouver English."

- Charles Boberg, "Sounding Canadian from Coast to Coast: Regional accents in Canadian English."

- Labov et al. 2006; Charles Boberg, "The Canadian Shift in Montreal"; Robert Hagiwara. "Vowel production in Winnipeg"; Rebecca V. Roeder and Lidia Jarmasz. "The Canadian Shift in Toronto."

- Boberg

- Labov, p. 221.

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 182.

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), pp. 173–4.

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), pp. 260–1.

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), pp. 238–9.

- Duncan (2016), pp. 1–2.

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 238.

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), pp. 178, 180.

- Boberg (2008), p. 145.

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), pp. 175–7.

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 183.

- Baker, Mielke & Archangeli (2008).

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), pp. 181–2.

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), pp. 82, 123, 177, 179.

- Labov (2007), p. 359.

- Labov (2007), p. 373.

- The Cambridge History of the English Language, edited by John Algeo, Volume 6, p. 431

- Bill Casselman. "Zed and zee in Canada". Archived from the original on 2012-06-26. Retrieved 2012-10-13.

- J.K. Chambers (2002). Sociolinguistic Theory: Linguistic Variation and Its Social Significance (2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. Retrieved 2012-10-13.

- Ballingall, Alex (6 July 2014). "How do you pronounce Lieutenant Governor?". www.thestar.com. Toronto Star. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- The pronunciation with the stress on the second syllable is the most common pronunciation, but is considered incorrect by some people. - Canadian Oxford Dictionary

- Kretzchmar, William A. (2004), Kortmann, Bernd; Schneider, Edgar W. (eds.), A Handbook of Varieties of English, Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter, p. 359, ISBN 9783110175325

- The pronunciation /ˈkɒrki/ was the one used by author and veteran Farley Mowat.

- Boberg (2020), p. 62.

- pecan /ˈpikæn, /piˈkæn/, /pəˈkɒn/ - Canadian Oxford Dictionary

- Vase. (2009). In Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Retrieved 2009-03-03.

- Barber, p. 77.

- Changes in Progress in Canadian English: Yod-dropping, Excerpts from J.K. Chambers, "Social embedding of changes in progress." Journal of English Linguistics 26 (1998), accessed March 30, 2010.

Bibliography

- Baker, Adam; Mielke, Jeff; Archangeli, Diana (2008). "More velar than /g/: Consonant Coarticulation as a Cause of Diphthongization" (PDF). In Chang, Charles B.; Haynie, Hannah J. (eds.). Proceedings of the 26th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics. Somerville, Massachusetts: Cascadilla Proceedings Project. pp. 60–68. ISBN 978-1-57473-423-2.

- Boberg, Charles (2008). "Regional phonetic differentiation in Standard Canadian English". Journal of English Linguistics. 36 (2): 129–154. doi:10.1177/0075424208316648.

- Boberg, Charles (2020). "Foreign (a) in North American English: Variation and Change in Loan Phonology". Journal of English Linguistics. 48 (1): 31–71. doi:10.1177/0075424219896397.

- Duncan, Daniel (2016). "'Tense' /æ/ is still lax: A phonotactics study" (PDF). In Hansson, Gunnar Ólafur; Farris-Trimble, Ashley; McMullin, Kevin; Pulleyblank, Douglas (eds.). Supplemental Proceedings of the 2015 Annual Meeting on Phonology. Proceedings of the Annual Meetings on Phonology. 3. Washington, D.C.: Linguistic Society of America. doi:10.3765/amp.v3i0.3653.

- Labov, William (2007). "Transmission and Diffusion" (PDF). Language. 83 (2): 344–387. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.705.7860. doi:10.1353/lan.2007.0082. JSTOR 40070845.

- Labov, William; Ash, Sharon; Boberg, Charles (2006). The Atlas of North American English. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-016746-7.