North-Central American English

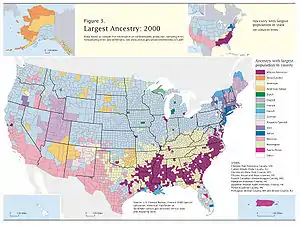

North-Central American English (in the United States, also known as the Upper Midwestern or North Central dialect, and stereotypically recognized as a Minnesota accent) is an American English dialect native to the Upper Midwestern United States, an area that somewhat overlaps with speakers of the separate Inland North dialect centered more around the eastern Great Lakes region.[1] If a strict cot–caught merger is used to define the North-Central regional dialect, it covers the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, the northern border of Wisconsin, the whole northern half of Minnesota, some of northern South Dakota, and most of North Dakota;[2] otherwise, the dialect may be considered to extend to all of Minnesota, North Dakota, most of South Dakota, northern Iowa, and all of Wisconsin outside of metropolitan Milwaukee.[3]

| North-Central American English | |

|---|---|

| Region | Upper Midwest |

Indo-European

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

The North Central dialect is considered to have developed in a residual dialect region from the neighboring distinct dialect regions of the American West, North, and Canada.[4] A North Central "dialect island" exists in southcentral Alaska's Matanuska-Susitna Valley, since, in the 1930s, it absorbed large numbers of settlers from Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin.[5] "Yooper" English spoken in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and Iron Range English spoken in Minnesota's Mesabi Iron Range are sub-varieties of the North Central dialect, largely influenced by Fenno-Scandinavian immigration to that area around the beginning of the twentieth century.

Phonological characteristics

Not all of these characteristics are unique to the North Central region.

Vowels

- /u/ and /oʊ/ are "conservative" in this region, and do not undergo the fronting that is common in some other regions of the United States.

- In addition to being conservative, /oʊ/ may be monophthongal [o]. The same is true for /eɪ/, which can be realized as [e], though data suggests that monophthongal variants are more common for /oʊ/ than for /eɪ/, and also that they are more common in coat than in ago or road, which may indicate phonological conditioning. Regionally, monophthongal mid vowels are more common in the northern tier of states, occurring more frequently in Minnesota and the Dakotas but much rarer in Iowa and Nebraska.[1] The appearance of monophthongs in this region is sometimes explained due to the high degree of Scandinavian and German immigration to these northern states in the late nineteenth century. Erik R. Thomas argues that these monophthongs are the product of language contact and notes that other areas where they occur are places where speakers of other languages have had an influence such as the Pennsylvania "Dutch" region.[6] An alternative account posits that these monophthongal variants represent historical retentions. Diphthongization of the mid vowels seems to have been a relatively recent phenomenon, appearing within the last few centuries, and did not affect all dialects in the UK. The monophthongs heard in this region may stem from the influence of Scots-Irish or other British dialects that maintain such forms. The fact that the monophthongs also appear in Canadian English may lend support to this account since Scots-Irish speech is known as an important influence in Canada.

- Some or partial evidence of the Northern Cities Vowel Shift, which normally defines neighboring Inland Northern American English, exists in North-Central American English. For example, /æ/ may be generally raised and /ɑ/ generally fronted in comparison to other American English accents.[7]

- Some speakers exhibit extreme raising of /æ/ before voiced velars (/ɡ/ and /ŋ/), with an up-glide rather than an in-glide, so that bag sounds close to beg or the first syllable of bagel in other dialects (other examples of where this applies include the word flag and agriculture). Sometimes the two are merged.[4]

- Raising of /aɪ/ is found in this region. It occurs before some voiced consonants. For example, many speakers pronounce fire, tiger, and spider with the raised vowel.[8] Some speakers in this region raise /aʊ/ as well.[9]

- The onset of /aʊ/ when not subject to raising is often quite far back, resulting in pronunciations like [ɑʊ].

- The cot–caught merger is common throughout the region,[4] and the vowel can be quite forward: [ɑ̈].

- The words roof and root may be variously pronounced with either /ʊ/ or /u/; that is, with the vowel of foot or boot, respectively. This is highly variable, however, and these words are pronounced both ways in other parts of the country.

- The Mary-marry-merry merger: Words containing /æ/, /ɛ/, or /eɪ/ before an "r" and a vowel are all pronounced "[ɛ]-r-vowel," so that Mary, marry, and merry all rhyme with each other, and have the same first vowel as Sharon, Sarah, and bearing. This merger is widespread throughout the Midwest, West, and Canada.

- The pen–pin merger does not occur.

- There is no Canadian shift.[4]

Other characteristics

North Central speech is rhotic. Word-initial th-stopping is possible among speakers of working-class backgrounds, especially with pronouns ('deez' for these, 'doze' for those, 'dem' for them, etc.). In addition, traces of a pitch accent as in Swedish and Norwegian can persist in some areas of heavy Norwegian or Swedish settlement, and among people who grew up in those areas (some of whom are not of Scandinavian descent).

History and geography

The appearance of monophthongs in this region is sometimes explained because of the high degree of Scandinavian and German immigration to these northern states in the late 19th century. Linguist Erik R. Thomas argues that these monophthongs are the product of language contact and notes that other areas where they occur are places where speakers of other languages have had an influence such as the Pennsylvania "Dutch" region.[10] An alternative account posits that these monophthongal variants represent historical retentions, since diphthongization of the mid vowels seems to have been a relatively recent phenomenon in the history of the English language, appearing within the last few centuries, and did not affect all dialects in the U.K. The monophthongs heard in this region may stem from the influence of Scots-Irish or other British dialects that maintain such forms. The fact that the monophthongs also appear in Canadian English may lend support to this account since Scots-Irish speech is known as an important influence in Canada.

People living in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan (whose demonym, and sometimes sub-dialect, is known as "Yooper," deriving from the acronym "U.P." for "Upper Peninsula"), many northern areas of the Lower Peninsula of Michigan, and in Northern Wisconsin are largely of Finnish, French Canadian, Cornish, Scandinavian, German, and/or Native American descent. The North Central dialect is so strongly influenced by these areas' languages and Canada that speakers from other areas may have difficulty understanding it. Almost half the Finnish immigrants to the U.S. settled in the Upper Peninsula, some joining Scandinavians who moved on to Minnesota. Another sub-dialect is spoken in Southcentral Alaska's Matanuska-Susitna Valley, because it was settled in the 1930s (during the Great Depression) by immigrants from the North Central dialect region.[5][11]

Grammar

In this dialect, the preposition with is used without an object as an adverb in phrases like come with, as in Do you want to come with? for standard Do you want to come with me? or with us?. In standard English, other prepositions can be used as adverbs, like go down (down as adverb) for go down the stairs (down as preposition). With is not typically used in this way in standard English (particularly in British and Irish English), and this feature likely came from languages spoken by some immigrants, such as Scandinavian (Danish, Swedish, Norwegian), German (includes Austrian), or Dutch (includes Flemish) and Luxembourgish, all of which have this construction, like Swedish kom med.[12][13]

Vocabulary

- breezeway or a skyway, a hallway-bridge connecting two buildings[14]

- frontage road, a service or access road[15]

- hotdish, a simple entree cooked in a single dish, like a casserole[16]

- pop or soda pop, a sweet carbonated soft drink[14]

- rummage sale, a yard or garage sale[15]

- Yooper, a person from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan[17]

Notable lifelong native speakers

- Steven Avery — "recognizably thick Wisconsin accent"[18]

- Michele Bachmann — "that calming, matzoh-flat Minnesota accent"[19]

- Jan Kuehnemund

- Brock Lesnar

- Don Ness — "You'll find that Ms. Palin and Duluth Mayor Don Ness don't sound all that different."[20]

- Julianne Ortman

- Sarah Palin[5] — "Listeners who hear the Minnewegian sounds of the characters from Fargo when they listen to Ms. Palin are on to something: the Matanuska-Susitna Valley in Alaska, where she grew up, was settled by farmers from Minnesota"[11]

In popular culture

The Upper Midwestern accent is made conspicuous, often to the point of parody or near-parody, in the film Fargo (especially as displayed by Frances McDormand's character Marge Gunderson) and the radio program A Prairie Home Companion (as displayed by many minor characters, especially those voiced by Sue Scott, with whom lead characters, most frequently male roles voiced by Garrison Keillor). It is also evident in the film New in Town.

See also

- Inland Northern American English

- North American English regional phonology

- Regional vocabularies of American English

- Yooper English

Notes

- Allen, Harold B. (1973). The Linguistic Atlas of the Upper Midwest. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-0686-2.

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 148

- "Map: North Central Region". Telsure Project. University of Pennsylvania.

- Labov, William; Sharon Ash; Charles Boberg (2006). The Atlas of North American English. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-016746-8.

- Purnell, T.; Raimy, E.; Salmons, J. (2009). "Defining Dialect, Perceiving Dialect, and New Dialect Formation: Sarah Palin's Speech". Journal of English Linguistics. 37 (4): 331–355 [346, 349]. doi:10.1177/0075424209348685. S2CID 144147617.

- Thomas, Erik R. (2001). An Acoustic Analysis of Vowel Variation in New World English. Publication of the American Dialect Society 85. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-6494-8

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:204)

- Vance, Timothy J. (1987). ""Canadian Raising" in Some Dialects of the Northern United States". American Speech. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. 62 (3): 195–210. doi:10.2307/454805. JSTOR 454805.

- Kurath, Hans; Raven I. McDavid (1961). The Pronunciation of English in the Atlantic States. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-8173-0129-1.

- Thomas, Erik R. (2001). An Acoustic Analysis of Vowel Variation in New World English. Publication of the American Dialect Society. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 85. ISBN 0-8223-6494-8.

- Pinker, Steven (October 4, 2008). "Everything You Heard is Wrong". The New York Times. p. A19.

- Spartz, John M (2008). Do you want to come with?: A cross-dialectal, multi-field, variationist investigation of with as particle selected by motion verbs in the Minnesota dialect of English (Ph.D. thesis). Purdue University.

- Stevens, Heidi (December 8, 2010). "What's with 'come with'? Investigating the origins (and proper use) of this and other Midwesternisms". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- Cassidy, Frederic Gomes, and Joan Houston Hall (eds). (2002) Dictionary of American Regional English. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Vaux, Bert, Scott A. Golder, Rebecca Starr, and Britt Bolen. (2000-2005) The Dialect Survey. Survey and maps.

- Mohr, Howard. (1987) How to Talk Minnesotan: A Visitor's Guide. New York: Penguin.

- Binder, David (14 September 1995). "Upper Peninsula Journal: Yes, They're Yoopers, and Proud of it". New York Times. p. A16.

- Smith, Candace (2016). "Seth Meyers forced back to work in hilarious ‘Making a Murderer’ spoof." New York Daily News. NYDailyNews.com

- Weigel, David (2011). "Michele Bachmann for President!" GQ. Condé Nast.

- "What Americans sound like". The Economist. The Economist Newspaper Limited 2011.

References

- Kortmand, Bernd; Schneider, Edgar W. (2004). A Handbook of Varieties of English. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-017532-5.

- Labov, William; Ash, Sharon; Boberg, Charles (2006). The Atlas of North American English. Berlin: Mouton-de Gruyter. pp. 187–208. ISBN 3-11-016746-8.