Cruralispennia

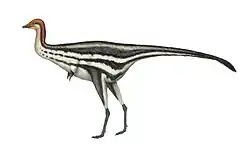

Cruralispennia is an extinct genus of enantiornithean bird. The only known specimen of Cruralispennia was discovered in the Early Cretaceous Huajiying Formation of China and formally described in 2017. The type species of Cruralispennia is Cruralispennia multidonta. The generic name is Latin for "shin feather", while the specific name means "many-toothed".The holotype of Cruralispennia is IVPP 21711, a semi-articulated partial skeleton surrounded by the remains of carbonized feathers.[1]

| Cruralispennia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photograph and interpretive drawing of IVPP 21711. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | †Enantiornithes |

| Genus: | †Cruralispennia Wang et al., 2017 |

| Type species | |

| Cruralispennia multidonta Wang et al., 2017 | |

Cruralispennia lived alongside several other species of enantiornitheans, such as Protopteryx, in the Sichakou Basin of the Huajiying Formation, approximately 130.7 million years ago. Despite being one of the earliest known ornithothoraces, this genus possessed several features of derived enantiornitheans as well as some unusual traits convergent with ornithuromorphs, a group containing modern birds. Cruralispennia are also notable for having crural feathers originally described as possessing a unique form unknown in any other feathered animal.[1] However, it has also been hypothesized that the holotype specimen had recently molted, and that the unusual feathers were simply new feathers which had yet to lose the thick sheath around the rachis.[2]

Description

Skull and vertebrae

Although most of the skull is poorly preserved, several elements are identifiable. The premaxilla is short and tall, while the rear part of the frontal is domed. The left dentary preserves fourteen teeth, a characteristically high number compared to other enantiornitheans. Although none of the teeth preserve complete crowns, there is a visible trend of the teeth becoming more buccolingually (side-to-side) flattened towards the back of the jaw.[1]

The spine is incomplete, but several articulated thoracic vertebrae preserve a lateral groove, characteristic of enantiornitheans. The fused pygostyle of IVPP 21711 is characteristically short and broad, tapering distally into an upturned tip. This is entirely unlike the long rod- or spear-like pygostyles known in other enantiornitheans, as well confuciusornithids and sapeornithids. Instead, its pygostyle is most similar to the plow-shaped pygostyles of ornithuromorphs. In modern birds, this form of pygostyle attaches to tail muscles which control the advanced pennaceous rectrices of their fan-shaped tails. However, its presence in IVPP 21711, which has simple, hair-like tail feathers, throws doubt on the hypothesis that a plow-shaped pygostyle always correlates to an advanced, fan-shaped tail.[1]

Forelimbs

Each coracoid of IVPP 21711 is slender, similar to those of advanced enantiornitheans. The thinnest part of the coracoid is the third which is furthest away from the sternum, while the widest is the half nearest the sternum. However, the edges of the coracoid are almost parallel near the sternum, unlike the coracoids of other enantiornitheans, which drastically splay outwards near the sternum, forming concave outer margins.[1]

The front of sternum has a pointed rostral spine, which is known in a few other enantiornitheans. The rear edge of the sternum has two pairs of thin rod-like structures. Although these structures are known in all but the most basal enantiornitheans, only IVPP 21711 has the inner pair extend the same distance as the outer pair. On the other hand, the V-shaped xiphoid region is similar to basal enantiornitheans such as Protopteryx and pengornithids. The forelimb is rather short, with a robust humerus possessing enantiornithean features. The hand is shorter than the humerus and the alular digit is reduced, both features characteristic of advanced enantiornitheans.[1]

Hind limbs

The postacetabular process of the ilium is characteristically short and tapering, and extends further downward than the ischiadic peduncle. The ischium is shorter than the pubis and has an upward pointing process midway down the shaft, similar to that of basal ornithuromorphs. There is no pubic foot, as in enantiornitheans. The tibiotarsus and tarsometatarsus are long and slender, but the fibula is short and tapering (as in advanced enantiornitheans and ornithuromorphs). The toe claws are sharp and curved.[1]

Feathers

Well-preserved feathers surround every part of the skeleton except the snout and feet. The body and tail feathers are short, hair-like, and do not have rachises. The feathers on the upper side of the neck are longer than those on the lower side. Asymmetrical pennaceous feathers are preserved attached to the wings, although they are shorter than in other enantiornitheans, being only twice the length of the hand.[1]

The most characteristic features of IVPP 21711, which the genus Cruralispennia was named after, are its crural (leg) feathers. These feathers are present on the tibiotarsus and possibly the femur, although overlap from body feathers makes the femur's integument uncertain. They are long and wire-like, consisting of a rachis-like structure seemingly formed from the fusion of a bundle of parallel barbs. This rachis-like structure forms 90% of the length of the feather. In the distal 10% of the feather's length, the individual parallel barbs become distinguishable, forming a brush-like tip. This form of feather morphology, dubbed "proximally wire-like part with a short filamentous distal tip (PWFDT)" , is also present in feathers projecting along the front edge of the left wing. PWFDT feathers are currently only known in Cruralispennia, although they are similar to the ribbon-like tail feathers of the oviraptorosaur Similicaudipteryx. It is probable that PWFDT feathers are a result of a genetic overexpression of the BMP4 gene (which promotes barb fusion and rachis formation) or a suppression of the Sonic hedgehog gene (which promotes the formation of individual barbs).[3]

Another possibility is that the PWFDT feathers are not a novel type of feather unique to Cruralispennia, but instead are immature pennaceous feathers formed after a recent molt. There are several lines of reasoning supporting this hypothesis. With a long, thick rachis and minimal barbs at the tip, the PWFDT feathers resemble moderately developed pin feathers, which are known from modern birds as well as newly described juvenile enantiornitheans. In addition, they are interspersed with mature feathers, while truly unique feather types are expected to be separated from typical feathers. Many of the specimen's feathers are loosely attached or separated from the rest of the specimen, adding further evidence to the hypothesis that it was molting when it died.[2]

Color

Structures believed to be fossilized melanosomes were found in five feather samples from the specimen using scanning electron microscopy.[1] Due to their rod-like shape, they were identified as eumelanosomes, which correspond to dark shades. Although specific colors were not stated in the analysis, other studies have shown that coloration in extant birds correlates to the length and aspect ratio (length to width ratio) of their eumelanosomes.[4] A sample taken from the crural feathers had eumelanosomes with the shortest aspect ratio, which may have corresponded to dark brown coloration. The highest aspect ratio eumelanosomes were found in a sample from the head feathers. High aspect ratios have been known to correlate with glossy or iridescent colors, although without knowing the structure of a feather's keratin layer (which does not fossilize well), no hue can be assigned for certain.[4] The wing and tail samples also had high aspect ratios, while the tail's eumelanosomes were the largest sampled.[1]

Classification

Cruralispennia was referred to Enantiornithes in the taxon's description due to various features of the humerus, a lack of procoracoid processes, and a long acromion process of the scapula. A phylogenetic analysis recovered Cruralispennia as a moderately advanced enantiornithean, more derived than basal members of the clade such as Protopteryx and pengornithids. Some of the derived features present within Cruralispennia include a reduced fibula and a short hand. However, the presence of a short, plow-shaped pygostyle in IVPP 21711 shows that Cruralispennia had some derived features which were very different from other enantiornitheans. Cruralispennia seemingly belongs to a previously undiscovered ancient lineage of enantiornitheans which had convergently evolved many ornithuromorph-like features. In addition, the presence of such a derived genus so early in the Cretaceous is evidence that the family tree of ornithothoraces is older than currently known fossils suggest.[1]

Paleobiology

A histological study of IVPP 21711's humerus found no lines of arrested growth present within the bone. This is evidence that IVPP 21711 died within one season. However, due to the bone having both an inner and outer layer, IVPP 21711 was believed to have died near adulthood. These factors are support for the idea that individuals of Cruralispennia grew quickly, reaching adult size in less than a year. This is in contrast with other enantiornitheans, which are believed to have grown slowly, taking several years to reach adulthood. Cruralispennia's growth strategies were more similar to those of Confusciusornis and ornithuromorphs, although slightly slower.[1]

It is difficult to determine the function of the crural PWFDT feathers (if they are unique in the first place), but several possibilities have been put forth. Some of these possible functions include insulation, heat shielding, or social signalling. Although PWFDT feathers were probably too simple to provide any aerodynamic advantage, their narrowness means that they were unlikely to have been an inhibiting factor either.[1]

References

- Wang, Min; O’Connor, Jingmai K.; Pan, Yanhong; Zhou, Zhonghe (2017-01-31). "A bizarre Early Cretaceous enantiornithine bird with unique crural feathers and an ornithuromorph plough-shaped pygostyle". Nature Communications. 8: 14141. doi:10.1038/ncomms14141. PMC 5290326. PMID 28139644.

- O'Connor, Jingmai K.; Falk, Amanda; Wang, Min; Zheng, Xiao-Ting (January 2020). "First report of immature feathers in juvenile enantiornithines from the Early Cretaceous Jehol avifauna" (PDF). Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 58 (1): 24–44. doi:10.19615/j.cnki.1000-3118.190823.

- O’Connor, Jingmai K.; Chiappe, Luis M.; Chuong, Cheng-ming; Bottjer, David J.; You, Hailu (2012-09-14). "Homology and Potential Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms for the Development of Unique Feather Morphologies in Early Birds". Geosciences. 2 (3): 157–177. doi:10.3390/geosciences2030157. ISSN 2076-3263. PMC 3758748. PMID 24003379.

- Li, Quanguo; Gao, Ke-Qin; Meng, Qingjin; Clarke, Julia A.; Shawkey, Matthew D.; D’Alba, Liliana; Pei, Rui; Ellison, Mick; Norell, Mark A. (2012-03-09). "Reconstruction of Microraptor and the Evolution of Iridescent Plumage". Science. 335 (6073): 1215–1219. doi:10.1126/science.1213780. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 22403389.

.png.webp)

.jpg.webp)