Jinguofortis

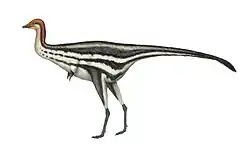

Jinguofortis is a genus of primitive avialan bird belonging to the clade Pygostylia that lived during the Valanginian stage of the Early Cretaceous. It was found in the Dabeigou Formation in northeastern China, and isotope dating from the samples overlying the bird-bearing horizon is 127 million years ago.[1]

| Jinguofortis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type specimen of Jinguofortis perplexus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Jinguofortisidae |

| Genus: | †Jinguofortis Wang et al., 2018 |

| Type species | |

| Jinguofortis perplexus Wang et al., 2018 | |

Description

Jinguofortis is notable for a mosaic of primitive and advanced characters, including a fused scapulocoracoid and highly reduced manual digits. A fused scapulocoracoid is a plesiomorphical feature that evolved before the origin of limb digits.[2] These two bones become separate and form a suture contact among some reptiles (e.g., lizards, crocodilian), but become fused independently in a few lineages, including non-avian dinosaurs and pterosaurs.[3] The tendency for fusion between the coracoid and scapula stems from their developmental origins as a unified homogenous condensation.[4] However, that coalescence becomes detached during chondrogenesis because the osteogenic pattern and/or the differentiation of the preskeletogenic cells is delayed,[2] resulting a sutural contact between the elements.

The fusion between the coracoid and scapula is present predominantly in non-avian theropods.[3] However, these two elements are separated in Archaeopteryx,[5] and in more crownward avian clades,[6][7] but fused in stemward pygostylians confuciusornithids and jinguornithids. The convergently evolved scapulocoracoid in jinguornithids and confuciusornithiforms suggests these basal clades likely reacquired a similar level of osteogenesis present in their non-avian theropod ancestors that is responsible for the co-ossification of the pectoral girdle.[1] Then separation of the coracoid and scapula becomes evolutionarily “fixed” (with a few exceptions in the crown groups) across Ornithothoraces, and underwent further modifications including an ossified sternal keel and formation of the triosseal canal. These developmental changes to the skeleton likely correspond to intense selective pressure to improve flight capability that eventually lead to the musculoskeletal system present among volant crown birds, suggesting developmental plasticity[8][9]

Jinguofortis is morphologically similar to the another stemward avialan Chongmingia (also preserved a fused scapulocoracoid). Differences from Chongmingia include: furcula less robust with a smaller interclavicular angle of 70°; pedal digit I approximately 70% of the length of digit II; and pedal digit II shorter than IV; and these two taxa are separated by approximately seven million years.[1]

Etymology

The name Jinguofortis is a combination of jinguo, from Mandarin (巾帼), referring to female warrior, and fortis, Latin for brave.[1]

Classification

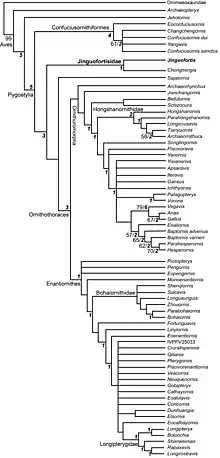

Wang et al. (2018) recovered Jinguofortis as a basal pygostylian more derived than Confuciusornithiformes, but more primitive than Sapeornithiformes, and as sister to the previously problematic genus Chongmingia.[1] Cladogram of Mesozoic birds[1]

References

- Wang M, Stidham TA, Zhou Z (October 2018). "A new clade of basal Early Cretaceous pygostylian birds and developmental plasticity of the avian shoulder girdle". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 115 (42): 10708–10713. doi:10.1073/pnas.1812176115. PMC 6196491. PMID 30249638.

- Vickaryous MK, Hall BK (March 2006). "Homology of the reptilian coracoid and a reappraisal of the evolution and development of the amniote pectoral apparatus". Journal of Anatomy. 208 (3): 263–85. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00542.x. PMC 2100248. PMID 16533312.

- Turner AH, Makovicky PJ, Norell MA (August 2012). "A Review of Dromaeosaurid Systematics and Paravian Phylogeny". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 20 (suppl): 1–207. doi:10.1206/748.1. hdl:2246/6352.

- Lawrence R (1960). The Avian Embryo: Structural and Functional Development. New York: The Macmillan Company.

- Mayr G, Pohl B, Hartman S, Peters DS (2007-01-01). "The tenth skeletal specimen of Archaeopteryx". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 149 (1): 97–116. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2006.00245.x.

- Jenkins F (January 1993). "The evolution of the avian shoulder joint". American Journal of Science. 293: 253–267. doi:10.2475/ajs.293.a.253.

- Zhou Z, Zhang F (July 2002). "A long-tailed, seed-eating bird from the Early Cretaceous of China". Nature. 418 (6896): 405–9. doi:10.1038/nature00930. PMID 12140555.

- Moczek AP, Sultan S, Foster S, Ledón-Rettig C, Dworkin I, Nijhout HF, Abouheif E, Pfennig DW (September 2011). "The role of developmental plasticity in evolutionary innovation". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 278 (1719): 2705–13. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0971. PMC 3145196. PMID 21676977.

- Standen EM, Du TY, Larsson HC (September 2014). "Developmental plasticity and the origin of tetrapods". Nature. 513 (7516): 54–8. doi:10.1038/nature13708. PMID 25162530.

.png.webp)

.jpg.webp)