Ctenosauriscus

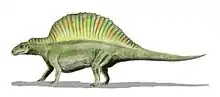

Ctenosauriscus is an extinct genus of sail-backed poposauroid archosaur from Early Triassic deposits of Lower Saxony in northern Germany. It gives its name to the family Ctenosauriscidae, which includes other sail-backed poposauroids such as Arizonasaurus. Fossils have been found in latest Olenekian deposits around 247.5-247.2 million years old, making it one of the first known archosaurs.

| Ctenosauriscus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Part slab of the holotype fossil of Ctenosauriscus koeneni | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Family: | †Ctenosauriscidae |

| Genus: | †Ctenosauriscus Kuhn, 1964 |

| Species | |

| |

History of discovery

Ctenosauriscus is known from the holotype, GZG.V.4191, a single partial preserved postcranial skeleton including partial vertebral column, ribs and girdle. The holotype is composed of four slabs, which were labeled A1, A2, B1, and B2 in a 2011 study. Slabs A1 and B1 form the part and slabs A2 and B2 form the counterpart. The holotype was discovered in early 1871 in the Bremke dell locality, near the county of Göttingen. The holotype was found in a deposit called the Solling-Bausandstein, which is an outcropping of the upper Middle Buntsandstein in the region of Eichsfeld. After the holotype was uncovered, it was housed in the University of Göttingen . It remained undescribed until 1902, when German paleontologist Friedrich von Huene designated it to the new species Ctenosaurus koeneni.[1]

Von Huene considered C. koeneni to be a late-surviving species of Pelycosauria, a group of distant mammal relatives otherwise known only from the Late Carboniferous and Early Permian. He based this classification on its similarity with sail-backed pelycosaurs like Dimetrodon. Austrian paleontologist Othenio Abel placed C. koeneni as a temnospondyl amphibian closely related to the sail-backed Platyhystrix (which, like Dimetrodon, was from the Early Permian).[2] The name Ctenosaurus was preoccupied by a species of iguanid lizard (now called Ctenosaura), so a new generic name, Ctenosauriscus, was erected by paleontologist Oskar Kuhn in 1964.[3] Paleontologist B. Krebs redescribed the holotype and reclassified Ctenosauriscus as an archosaur based on similarities with the sail-backed pseudosuchian Hypselorhachis from the Middle Triassic Manda Beds of Tanzania.[2]

Ctenosauriscus was found in the Solling Formation, which was deposited about 247.5 to 247.2 million years ago in the latest Olenekian stage. This age is based on radiometric dating and records of Milankovitch cycles in the formation. Ctenosauriscus was traditionally thought to have lived during the Middle Triassic after Krebs placed the Middle Buntsandstein within the Anisian stage.[2]

A redescription of the holotype was published by Richard J. Butler, Stephen L. Brusatte, Mike Reich, Sterling J. Nesbitt, Rainer R. Schoch and Jahn J. Hornung in 2011. They did not identify any autapomorphies for Ctenosauriscus, but they noted that the holotype can be distinguished from other ctenosauriscids by a unique combination of characters. Ctenosauriscus is one of the oldest archosaurs to date, along with Vytshegdosuchus from Russia and probably Xilousuchus, a ctenosauriscid from China.[2]

Description

The most prominent feature of Ctenosauriscus is its sail-like back, formed from elongated neural spines of the dorsal and cervical vertebrae. These spines curve slightly forward at the front of the sail and slightly backward at the back of the sail. Although other poposauroids like Lotosaurus and the ctenosauriscids Hypselorhachis and Xilousuchus also have elongated spines, the sail of Ctenosauriscus is one of the largest in the group. Among ctenosauriscids, Ctenosauriscus is most similar to Arizonasaurus from the Middle Triassic of the southwestern United States. Both of these ctenosauriscids have elongated vertebrae spines up to 12 times the height of the bodies of the vertebrae. The ends of the spines are wider in Ctenosauriscus, and Ctenosauriscus also has larger projections on the centra of the dorsal vertebrae. Hypselorhachis also has neural spines that are widened at the end, but they are shorter than those of Ctenosauriscus. Lotosaurus from the Middle Triassic of China also has elongate spines, but they are straighter, broader, and much shorter than those of Ctenosauriscus.[2]

Paleobiology

A 1998 study proposed that Ctenosauriscus was bipedal and that its elongated neural spines served to absorb the forces exerted from walking on two legs. Although limb bones are unknown, the study found that forces on the tips of the spines were focused on a point below the spinal column, hypothesized to be the knee joint.[4] In the 2011 redescription of Ctenosauriscus, the authors rejected this idea because for forces on the spine to meet at the knee joint, muscles would have to form a direct connection between the knee and the back. Forces exerted from movement travel from the hind legs to the hip and sacral vertebrae, not the dorsal vertebrae. The sail of Ctenosauriscus would also have shifted its center of weight toward the front of the body, making bipedal locomotion difficult or impossible.[2]

References

- Friedrich von Huene (1902). "Übersicht über die Reptilien der Trias [Review of the Reptilia of the Triassic]. Geologische und Paläontologische Abhandlungen (Neue Serie)". Gustav Fischer Verlag, Jena. 6: 1–84.

- Richard J. Butler; Stephen L. Brusatte; Mike Reich; Sterling J. Nesbitt; Rainer R. Schoch; Jahn J. Hornung (2011). "The sail-backed reptile Ctenosauriscus from the latest Early Triassic of Germany and the timing and biogeography of the early archosaur radiation". PLoS ONE. 6 (10): e25693. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025693. PMC 3194824. PMID 22022431.

- Oskar Kuhn (1964). "Ungelöste Probleme der Stammesgeschichte der Amphibien und Reptilien". Jahreshefte des Vereins für vaterländische Naturkunde in Württemberg. 118–119: 293–325.

- Ebel, K.; Falkenstein, F.; Haderer, F.-O.; Wild, R. (1998). "Ctenosauriscus koeneni (v. Huene) und der Rauisuchier von Waldshut - Biomechanische Deutung der Wirbelsäule und Beziehungen zu Chirotherium sickleri Kaup". Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde, Serie B (Geologie und Paläontologie). 261: 1–18.