Cultural impact of Madonna

Since the beginning of her career in the early 1980s, American singer and songwriter Madonna has had a social-cultural impact on the world through her recordings, attitude, clothing and lifestyle. Called the "Queen of Pop", Madonna is labeled by international authors as the greatest woman in music, as well as the most influential and iconic female recording artist of all time.

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

A global cultural icon, Madonna has built a legacy that goes beyond music and has been studied by sociologists, historians and other social scientists.[1] Her impact is often compared with that of Elvis Presley, the Beatles and Michael Jackson; they are the best selling acts of all time in the general, solo male and female category respectively.[2] Madonna is a key figure in popular music; critics have retrospectively credited her presence, success and contributions with paving the way for every female artist and changing forever the music scene for women in the music history, as well as for today's pop stars. Even reviews of her work have served as a roadmap for scrutinizing women at each stage in their music career.[3]

Madonna is the first multimedia pop icon in history and professionals agree that she has become the world's biggest and most socially significant pop icon, as well as the most controversial. However, some intellectuals, like the Frenchman Georges Claude Guilbert, felt that she has greater cultural importance, like a myth, that has apparent universality and timelessness. References to Madonna in popular culture are found in the arts, food, science and each branch of entertainment. In a general sense, journalist Peter Robinson noted that "Madonna invented contemporary pop fame so there is a little bit of her in the DNA of every modern pop thing."[4]

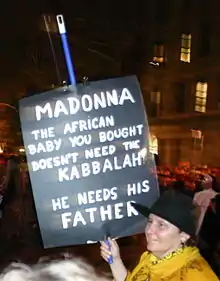

However, she is not only an omnipresent figure, but also a polarizing one. During her career, Madonna has attracted contradictory cultural social attention from family organizations, feminist "anti-porn" and religious groups worldwide with boycott and protests.

Cultural and social impact

Madonna has been described as an "omnipresent" character and one of the most recognizable names and faces in the world.[5][6][7] Author David Tetzlaff felt that "the power of the omnipresent Madonna has to do with hyperreality, but an infinite accumulation of simulacra, an overabundance of information".[8] Journalist Quico Alsedo from El Mundo in Spain felt that Madonna has built a nation, landless but densely populated.[9] Music critic T. Cole Rachel, stated in 2015, that "there’s an approximate 100% probability that any living human over the age of, say, 25 has some sort of specific Madonna-related memory... Even if you aren’t a super fan—or even a fan at all—there’s no escaping Madonna. She is everywhere."[10]

In his book Madonna As Postmodern Myth (2002), French academic Georges Claude Guilbert explains how Madonna reflects today's society,[11] while William Langley from The Daily Telegraph feels that "Madonna has changed the world's social history, has done more things as more different people than anyone else is ever likely to."[12] American poet Jane Miller compares her functions as an archetype directly inside contemporary culture with the Black Madonna.[13] Professor John R. May concludes that Madonna is a contemporary "gesamtkunstwerk",[14] and academic Sergio Fajardo labels her "a very powerful symbol".[15] Scholar Belén González Morales of the Autonomous University of Barcelona comments, "'The infinite dissection' of Madonna is like a body paradigmatic of the global age that emanating a tremendous amount of meanings ... Madonna has been become a cultural artifact.[16] Strawberry Saroyan states that she's a storyteller and a cultural pioneer, and emphasizes the important thing is her message: "And all of those things have been brilliantly of a piece. Madonna's ability to take her message beyond music and impact women's lives has been her legacy".[17]

Authors note that Madonna has proved a master of cultural appropriation.[18] She is also considered "a barometer of culture that directs the attention to cultural shifts, struggles and changes."[19] The American Library Association, in a review of music journalist Adam Sexton's book Desperately Seeking Madonna: In Search of the Meaning of the World's Most Famous Woman, remarks: "Love her or hate her, Madonna is an inescapable figure in the contemporary cultural landscape".[20] Musicologist Susan McClary suggests that Madonna is engaged in rewriting some very fundamental levels of Western thought.[21] One academic from Lehigh University expressed that she stands behind all people and helps them fight against being ostracized in society.[22] Contributor from company Spin Media felt that "Madonna has changed society through her fiery ambition and unwillingness to compromise".[23] Professor Karlene Faith asserted Madonna's peculiarity is that she has cruised so freely through so many cultural terrains. She has been a 'cult' figure within self-propelling subcultures just as she became a major". She also concluded that as fans, moral critics, media journalists, or university scholars, we mediate what Madonna means to our society.[24] In general, academic radicals turned Madonna into the "cottage industry", most notable in the 1990s.[25]

In United States

Madonna is part of the Culture of United States and an American icon. She was included in The Greatest American. Authors in American Icons (2006) felt that "like Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley or Coca-Cola, Madonna image is immediately recognizable around the world and instantly communicates many of the values of U.S. culture".[26] Rodrigo Fresán commented: "saying that Madonna just is a pop star is as inappropriate as saying that Coca-Cola is just a soda. Madonna is one of the classic symbols of Made in USA".[27] She was included in the book 100 Entertainers Who Changed America: An Encyclopedia of Pop Culture of Greenwood Publishing Group. Historian professor Glen Jeansonne, said that "Madonna freed Americans from their inhibitions and made them feel good about having fun".[28] Editor Erin Skarda from Time felt that essentially redefined what it meant to be famous in America.[29] Author in Shaded Lives: African-American Women and Television (2002), said that only Madonna rivaled the space Oprah Winfrey occupied in the late twentieth century and in the psyche of national culture.[30] Karen Lac in her Madonna's biography concluded that she is one of those rare people who have become a part of American culture itself.[31] Jim Cullen wrote in Restless in the Promised Land: Catholics and the American Dream (2001) "few figures in American life have managed to exert as much control over their destinies as she has, and the fact that se has done so as a woman is all the more remarkable. That Madonna has done this is indisputable".[32]

In American society, she is often referenced by her sexual feminist political movement. For example, Sara Marcus from Salon.com felt that with the height of her career, Madonna brought the changes to American culture and expressed that "her revelatory spreading of sexual liberation to Middle America, changed this country for the better. And that's not old news; we're still living it.... as we can see in everything from the ubiquity of pop stars to Rihanna's career. She ends saying that "the woman [Madonna] remade American culture".[33] Andrew O'Hagan felt that "Madonna is like a heroic opponent of cultural and political authoritarianism of the American "establishment".[34] Cultural critic Annalee Newitz commented that Madonna has given to American culture, and culture throughout the world, is not a collection of songs; rather, it is a collection of images.[35] USA Today dubbed her as "our lady of constant makeovers".[25] And Lynn Spigel wrote that Madonna intervened "America's notions of sex, gender and power. Madonna publicized her appropriation of the unspoken and taboo areas of America's moralist rhetoric and capitalized on it through the scandalization and titillation of the consumer".[36]

Madonna as an icon

Dubbed as the most iconic female artist of all time,[37] Madonna is a synonym of vanguard in the fields of her work.[38] By her impact and contributions, she has been analyzed from the point view of several studies, including feminist, sexual, gay, queer, musical, social and postmodern etc., becoming known as an icon in all these branches. Reader editor Brian McNair wrote that "Madonna more than made up for in iconic status and cultural influence".[39] Professor Dennis Hall said that "the fact that not only her work but her person was open to multiple interpretations contributed to the rise of Madonna Studies".[40] As Hall, Hao Huang in his 1999 book Music in the 20th Century wrote that Madonna has made a career as well as an art out of reinventing herself — as a rock diva, stage and screen star, video vixen, fashion icon, and cultural phenomenon.[41]

Academics felt that Oxford English Dictionary's recent definition of "icon" as a "person or thing" or an "institution", etc., considered worthy of admiration or respect or "regarded as a representative symbol", esp. of a culture or movement” (OED 2009), can be used to describe Madonna.[42] Alyson Welsh from The Guardian commented that "she is an amazing role model, and a cultural icon".[43] The program Australasian Journal of American Studies (AJAS) remember that it's not an accident that Mickey Mouse and Madonna are worldwide icons.[44]

Professors from Heidelberg University shows how Madonna's "iconicity" is indeed that of a "meta-icon" in the sense that the self-reflexive imitation of celebrity poses. Calls this strategy "iconizing", in analogy to the concept of "vogueing". The essay also inquires into the blend of biography and performativity that can be said to underlie Madonna's "iconizing" in relation to the performance artists.[42] Michelle Goldberg said that "Andy Warhol did an enormous amount to change that idea in highbrow circles, but Madonna made it conventional wisdom to conflate art and commerce. She pioneered this kind of multimedia, 'life as performance art'."[17]

Before closing the 20th century, Q magazine declared her as one of the most important cultural figures of this century.[45] Miranda Sawyer, Jefferson Hack and others authors called to her as a 21st-century icon.[46][47] Andrew Morton wrote in his book Madonna (2002) that "she is the undisputed female icon of the modern age". Also cited as one of the most fascinating women and enigmatic in current history.[48] Madonna in Art (2004) is a book by Mem Mehmet where included the work art by over a hundred artists, including Andrew Logan, Sebastian Krüger, Al Hirschfeld, and Peter Howson. The book is a testament to her unique global impact.[49] French biographer Anne Bleuzen wrote that she is "interplanetary",[50] and Italian author Francesco Falconi felt that she is an icon eternal.[51] Editor Eduardo Gutiérrez Seguro from Latin magazine Quién wrote:

Her Majesty: music and pop culture would not be the same [without Madonna]. Madonna set a precedent never seen for a singer, before her, eroticism was not a must—per very disguised form it takes, in the scenes videos or lyrics—. Feminism underwent a complete makeover and the formula surprise/offense the public has she placed in the Everest of show business.[52]

Music

Rolling Stone described her as a musical icon without peer,[53] while RTL Television Belgium said that "Madonna is a key figure in the music".[54] Bill Wyman, editor of Chicago Reader, wrote that she is a "genuinely freakish figure in popular music".[55] According to international media and critics, Madonna is the most influential female recording artist of all time,[37][56][57] and the greatest woman in music history.[58][59]

Her contributions on music are generally praised by critics, which have also been known to induce controversy. Tony Sclafani from company MSNBC felt that her Madonna's impact and effect on the future direction of music bests The Beatles, even that quarter century after Madonna emerged, artists still use her ideas and seem modern and edgy doing so.[60] Laura Barcella in her book Madonna and Me: Women Writers on the Queen of Pop (2012) wrote that "really, Madonna changed everything the musical landscape, the '80s look du jour, and most significantly, what a mainstream female pop star could (and couldn't) say, do, or accomplish in the public eye."[61] Similar to Barcella, Joe Levy Blender editor in chief, "opened the door for what women could achieve and were permitted to do".[62]

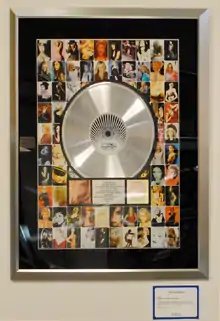

In the music industry, Madonna was the first female to have complete control of her music and image.[63][64] Authors noted that before Madonna, records labels determined every step of artists, but she introduced her style and conceptually directed every part of her career; the music industry was the foundation to permanently change the way the record companies treat artists.[1] Journalist Carol Benson wrote that Madonna entered the music business with definite ideas about her image, but it was her track record that enabled her to increase her level of creative control over her music.[65] Many years after, she founded Maverick Records which became the most successful "vanity label" in the history of music. While under Madonna's control it generated well over $1 billion for Warner Bros. Records, more money than any other recording artist's record label.[66][67]

Critics felt in retrospect that Madonna's presence is defined for changing contemporary music history for women's, mainly rock, dance and pop scene.[23][60][61][68][69][70][71] Also, she is cited that open the doors for the future hip-hop explosion and approach to sex to her music.[60] Erin Vargo from online magazine in popular culture, felt that "Madonna has fought for freedom of expression by female artists. Her legacy has paved the way for today’s pop, hip-hop, and rock artists to get into their own groove".[72] The Times stated: "Madonna, whether you like her or not, started a revolution amongst women in music ... Her attitudes and opinions on sex, nudity, style and sexuality forced the public to sit up and take notice".[73] The New York Post writer Brian Niemietz, who found that Madonna revolutionized dance music much the same way Elvis Presley invented gospel and rock and roll.[74]

Pop star

—Author Art Tavana from company Spin Media.[23]

Madonna is a pop star icon.[75] According to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Madonna is the first multimedia figure in the history of popular culture.[5] Peter Robinson from The Guardian felt that "Madonna pretty much invented contemporary pop fame so there is a little bit of her in the DNA of every modern pop thing".[4] Rolling Stone of Spain wrote that "Madonna became the first viral Master of Pop on history, years before the Internet was massively used." Madonna was everywhere; in the almighty music television channels, 'radio formulas', magazine covers and even in bookshops. A pop dialectic, never seen since The Beatles's reign, which allowed her to keep on the edge of tendency and commerciality".[71] Also, Caryn Ganz from the same magazine wrote that "Madonna is the most media-savvy American pop star since Bob Dylan and, until she toned down her press-baiting behavior in the nineties, she was the most consistently controversial one since Elvis Presley.[76] Music critic Stephen Thomas Erlewine felt that "one of Madonna's greatest achievements is how she has manipulated the media and the public with her music, her videos, her publicity, and her sexuality".[64] Becky Johnston from Interview magazine commented: "[F]ew public figures are such wizards at manipulating the press and cultivating publicity as Madonna is. She has always been a great tease with journalists, brash and outspoken when the occasion demanded it, recalcitrant and taciturn when it came time to pull back and slow down the striptease".[77]

Academic Becca Cragin explain that "Madonna has managed to hold the public's attention for 30 years now, in large part because of her skillful use of the visual in expressing herself and marketing her music".[18] French academic Georges-Claudes Guillbert wrote that taking some elements and transforms them into commercial products. Cultural critic, Douglas Kellner explained that Madonna's popularity also requires focus on audiences, not just as individuals, but as members of specific groups.[78] Journalist Mark Watts felt that the rise and (perceived) decline of Madonna has gone, so to say, hand-in-hand with that of postmodern theory.[79] According to journalist Annalee Newitz, "the academics in the fields of theology to queer studies have written literally volumes about what Madonna's fame means for gender relations, American culture, and the future".[35] As Newitz, author in Images of women in American popular culture (1995) said that Madonna had reached such staggering celebrity that scholarly and popular assessments of the meaning of her work for the future of feminism, for the sexual values of the young.[80] In this way, many authors, including Alvin Hall and Matthew Rettenmund (Encyclopedia Madonnica; 1995), agree that Madonna is "the world's greatest artist" while others classify her as "the most powerful celebrity or famous woman in the world".[20][81][82] Music editor Bill Friskics-Warren wrote that "Madonna's megastardom and cultural ubiquity had made her as much a social construct as anything else, a "person-turned-idea," as Steve Anderson put it, along the iconic lines of Elvis Presley or Marilyn Monroe".[83]

Mainstream

Called to as a "mainstream hero" by professor Karlene Faith,[24] Madonna is the best-selling woman artist in the history,[37] and the most successful female recording artist of all time certified by Guinness Book of Worlds Records.[84] With several critics feeling that she paved the way for every female artist,[68] Time magazine expressed that "every pop star of the last two or three decades has Madonna to thank in some part for his or her success".[85] She is cited like an influence by many other artists worldwide.

Her superstardom also is cited as the motivation of the success commercial and popularised or introduction of several things like branches, terms, groups, cultures, persons and products. For example, the media cited her acting in the movie Evita, that popularised Argentinian politics and she put the nation Malawi on the map while she launched the trend for celebrity adoption.[37][86] Madonna's success open to other celebrities such as singers, actors and politicians have successfully dabbling in the publishing field for young audiences.[87] Mark Blankenship felt her first book Sex "changed publishing history".[88] Her album Something to Remember set a trend of releasing ballad albums afterward, such as the 1996 albums Love Songs by Elton John and If We Fall in Love Tonight by Rod Stewart.[89]

She popularizing the Voguing. Academic Stepehn Ursprung from Smith College felt that "Madonna created a market for Voguing in the commercial entertainment world". Analyzed that "through a close connection with the continued commercial success of Madonna, Voguing has left its mark on the world largely... Voguing was first appropriated by pop culture by pop music icon Madonna".[90] The website Wallblog (Haymarket Media Group) from United Kingdom called tentatively in a question, to Yahoo! like the "Madonna of digital media".[91] Even, is cited that she has carried the burlesque to mass culture.[92] As is cited that MTV helped her, some authors like Josue Rich from Entertainment Weekly felt that Madonna helped make MTV (alongside Michael Jackson).[93] Biographer Mick St Michael wrote that "girl power began with Madonna".[94] Also, she has credit for the introduction of electronic music to the stage of popular music,[95] and innovated the rave culture.[96][97] Similar, music critic Stephen Thomas Erlewine felt that Madonna introduced the dance pop to mainstream scene.[98]

According to some cultural critics like Douglas Kellner, the phenomenon of femininity inspired by South Asia as a tendency in Western media could go back to February 1998 when the pop icon Madonna released her video for "Frozen". They explained that "although Madonna did not initiate the Indian fashion accessories beauty [...] took the public eye to attract the attention of the global media.[99] The Spanish style of Madonna in the video "La Isla Bonita" became popular and was reflected in fashion trends of the time in the form of "boleros", skirts with tables and rosaries and crucifixes as accessories.[100] According to the official website of the city Safed, Madonna popularized the Jewish mysticism.[101] Madonna set a trend that influenced people to take interest in the sexuality of women's bodies.[102] In general, some authors like entertainment critic Rogelio Segoviano felt that "the fever for queen of pop does not yield to the passage of time".[103]

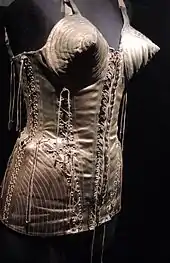

Fashion

Time included her as one of the Top 100 Icons of all time in fashion, style and design.[29] Critics praised Madonna's style during her career, which became the defining look in the 80s.[86] This gave rise to the term of Madonna wannabe. To experts in the 1990s, her use of fashion was even more eclectic.[104]

Journalist Michael Pye felt that "the face that launched a thousand fashions. To a large extent Madonna not only makes fashion, she is fashion.[105] Editor of Vogue magazine Anna Wintour declared:

She's a perfect example of how popular culture and street style now influence the world of fashion. Over the years, Madonna has been one of the most potent style setters of our time. She, just as much as Karl Lagerfeld, makes fashion happen.[105]

Professors in Oh Fashion (1994) book wrote that "the Madonna phenomenon suggests that in a postmodern image culture identity is constructed through image and fashion, involving one's look, pose, and attitude. Fashion and identity for Madonna are inseparable from her aesthetic practices, from her cultivation of her image in her music videos, films, TV appearances, concerts, and other cultural interventions".[106] Billboard declared that "no pop diva has reinvented her fashion image with the consistency and creativity of Madonna... she evolved into a fashion-forward icon whose sense of style became as influential as her chart-topping tunes".[107] Similarly, editor of The Huffington Post Dana Oliver comments why Madonna is the ultimate style chameleon and added that "no one has transformed herself like Madonna. She has had about as many looks as she has records. Her ability to constantly reinvent herself and her music has helped to secure her status as an icon, and she has influenced a generation of copycats. In short, no one has had more diverse looks than Madonna".[108]

Chloe Wyma from Louise Blouin Media commented that Madonna's chameleon attitude in transforming her fashion has become a universally recognized fact.[109] Ana Laglere from Batanga Media expressed that "each new Madonna's style is a trend and is used by major designers as inspiration, flooding our world with innovative ideas".[1] Cynthia Robins from San Francisco Chronicle said that "when Madonna came along, all fashion hell broke loose. Thus far, her influence on fashion —high, low and otherwise— has transmogrified from 'Who's That Girl?' to what in the world will Madonna wear next?".[110] Alessandra Codinha from Vogue named as "the master of reinvention".[111]

Feminism

Madonna as a feminist icon has generated variety of opinions worldwide. She is frequently associated with the feminist movement and she is considered a revolutionary figure who questioned the boundaries of gender. She is also responsible for influencing the mentality and behavior of women and how society interprets these changes.[1] Professor Sut Jhally felt that "Madonna is as an almost sacred feminist icon".[112] Academic Camille Paglia from University of the Arts called Madonna a "true feminist" and noted that "she exposes the puritanism and suffocating ideology of American feminism, which is stuck in an adolescent whining mode". According to her, "Madonna has taught young women to be fully female and sexual while still exercising total control over their lives".[113] Psychologist Jule Eisenbud in Sex Symbols (1999) noted that Madonna's refusal to accept that power and femininity is equivalent to masculinity has allowed her to maintain her status as a sex symbol.[114]

Jessica Valenti wrote in her book Madonna and Me: Women Writers on the Queen of Pop (2012) "sure, one Madonna gave birth to Jesus... but our Madonna gave birth to "femme-inism".[115] Spanish newspaper Periódico Diagonal convened a researchers panel discussion her as a feminist icon.[92] One of the comments, included that "she democratized the idea of women as protagonists and as agents of their own action", while some ambiguous ones stated that she contributed to women's empowerment of a few Western women, straight and gay middle class, but that empowerment is not feminism, because it is individualistic. Madonna was included in The Guardian list of the Top 100 women and editor Homa Khaleeli declared "no matter the decade or the fashion, she has always been frank about her toughness and ambition". She is still one of the most famous women on the planet and "she inspires not because she gives other women a helping hand, but because she breaks the boundaries of what's considered acceptable for women".[116]

Sex symbol

Madonna has been referred to as a sexual icon,[30][117] and sex symbol; most notable in the decade of the 1980s and 1990s.[118] Also, she is cited as an icon of sexual freedom and expression.[51] Author Courtney E. Smith in the 2011 book Record Collecting for Girls noted that most people associate Madonna with sex.[119] Chuck Klosterman in his book Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs (2003) wrote that "whenever I hear intellectuals talk about sexual icons of the present day, the name mentioned most is Madonna".[120] Even, Karen Fredericks from socialist newspaper Green Left Weekly in comment with her sexual attitude said that Madonna capturing an enormous mainstream audience, has had a perhaps surprising impact in progressive circles.[121] Greta Gaard's article writes, "Madonna's music videos enact the theory that gender is only one component of sexual identity-and a manipulpable one at that".[122]

Artists Adam Geczy and Vicki Karaminas in Queer Style (2013) noted Madonna transmogrified from virgin to dominatrix to Über Fran, each time achieving iconic status. Added Madonna was the first woman to do so-and with mainstream panache and approbation.[123] bell hooks teach that her "power to the pussy" credo worked only to solidify Madonna's positioning on the backs of the marginalized. The sexual icon she constructed may indeed, then, accord power to the pussy.[123] Academics from European School of Management and Technology felt that Madonna became one of the world's first performers to manipulate the juxtaposition of sexual and religious themes.[7] American editor Janice Min wrote that "long before Sex and the City, Madonna owned her sexuality. She made people cringe but also think differently about female performers. Her role as a provocateur changed boundaries for ensuing generations. She was a one-woman reality show."[62] As Min, Shmuel Boteach, author of Hating Women (2005), felt that Madonna was largely responsible for erasing the line between music and pornography. He stated: "Before Madonna, it was possible for women more famous for their voices than their cleavage to emerge as music superstars. But in the post-Madonna universe, even highly original performers such as Janet Jackson now feel the pressure to expose their bodies on national television to sell albums".[124]

During her career, Madonna has several provocative works. Perhaps, her book Sex is most notorious, considered by many as the artist's most controversial and transgressive period.[125] Some authors noted that Sex helped Madonna make a name in the porn industry,[126] and earned her the title of S&M's first cultural ambassador.[127] Steve Bachmann, on his book Simulating Sex: Aesthetic Representations of Erotic Activity pointed out that "perhaps one of the most interesting aspects of Madonna's sexual phenomenon is the extent to which her book marked a new threshold in the pornographic franchise".[128] Brian McNair, author of Striptease Culture: Sex, Media and the Democratisation of Desire (2012) praised this period of Madonna's career, saying that she had "porno elegance" and that "Sex is the author of a cultural phenomenon of global proportions [due to the critics] and thanks to this Madonna established her iconic status and cultural influence.[129] Professors in Oh Fashion (1994) book felt that "Madonna is a toy for boys, but on another level boys are toys for her".[104]

Queer and gay

According to The Advocate, Madonna is the greatest gay icon of all time.[130] New Statesman reported that Madonna became the supreme gay icon, and the Madonna Studies analyzed and support these.[131] Scholars Carmine Sarracino and Kevin Scott in The Porning of America (2008), wrote that Madonna "gained particular popularity with gay audiences, signaling the creation of a career-long fan base that would lead to her being hailed as the biggest gay icon of all time".[132] Out magazine wrote that Madonna "stuck her neck out and positioned herself to be a gay icon before it was cool to be one".[133]

Associate professor Judith A. Peraino wrote that "no one has worked harder to be a gay icon than Madonna, and she has done so by using every possible taboo sexual in her videos, performances, and interviews".[134] Similar, Alex Hopkins from Time Out magazine denoted that gay community labeled her as [Their] 'Glorious Leader', "Madge is part of our subculture's rich history of diva worship. She has referenced every sacred monster from Dietrich to Monroe, reveled in upfront, often transgressive sexuality and demonstrated a highly developed sense of camp. No wonder we loved her". Also, her lack of inhibition helped inspire a generation of gay men and women to live on their own terms.[135]

Madonna is also referred to as a queer icon and icon of queerness. Theologist, Robert Goss wrote: "For me, Madonna has been not only a queer icon but also a Christ icon".[136] Similar Sheila Whiteley from Sexing the Groove: Popular Music and Gender (2013) felt that "Madonna came closer to any other contemporary celebrity in being an above-ground queer icon".[137]

Postmodern

According to Lucy O'Brien: Much has been made of Madonna as a postmodern icon, yet all her reference points have been resolutely modernist—from Steinbeck and Fitzgerald to Virginia Woolf and Sylvia Plath, to her predilection for narrative and psychoanalysis.[138]

Canadian editor Richard Appignanesi wrote that for some "Madonna is the cyber-model of the New Woman.[139] Similar, senior lecturers Stéphanie Genz and Benjamin Brabon in Postfeminism: Cultural Texts and Theories (2009) felt that "whether it is as a woman, mother, pop icon or fifty year old, the American singer challenges our preconceptions of who 'Madonna' is and, more broadly, what these identity categories mean within a postmodern context".[140]

Pop icon and honorific nicknames and titles on popular culture

Madonna as a pop icon and figure on popular culture has generated scrutine analysis, but some journalists and critics like Carol Clerk wrote that "during her career, Madonna has transcended the term 'pop star' to become a global cultural icon".[141] However, academics from Rutgers University comments that "Madonna has become the world's biggest and most socially significant pop icon, as well as the most controversial".[142] Critical theorist Douglas Kellner described her as "a highly influential pop culture icon" and "the most discussed female singer in popular music".[143] Even, in 2012 Latin critics felt that Madonna is the most influential presence of current popular culture.[92] Historian Jasmina Tešanović like others authors, noted that Madonna's changes are well-calculated in order to be ahead of the curve, of the game, to dictate the fashion, to be a trendsetter and called her as one of the most honest performers in pop culture.[18] VH1 listed her behind David Beckham as the greatest pop icon of all time.[144]

William Langley from The Daily Telegraph noted that Madonna "remains a permanent fixture on every list of world's most powerful/admired/influential women."[145] For example, The Sun listed her in the topping of "the 50 female singers who will never be forgotten".[146] American journalist Edna Gundersen felt that Madonna is "durable pop triumvirate".[62] Also, she has been referred to as a "modern Medusa" or "queen of gender disorder and racial deconstruction".[19]

Madonna has several titles, subjectives and superlatives, many of them explain and explore her large impact in many fields. Blogger Richard Pérez-Feria posted on The Huffington Post that "over the course of her remarkable career, Madonna has been called many things... whore, which, for vastly different reasons. What Madonna ultimately achieved is nothing less than reigning as the universe's Queen of Pop, as in music, culture, life".[147] Chilean newspaper of politics, economy and culture, Qué Pasa stated in 1996, that "to Madonna can be attributed many titles and never be exaggerated. She is the undisputed queen of pop, sex goddess, and of course marketing".[148] Music blogger Alan McGee from The Guardian felt that Madonna is post-modern art, the likes of which we will never see again. He further asserted that Madonna and Michael Jackson invented the terms Queen and King of Pop.[149] Like a corollary, her most notable nickname in world popular culture is Queen of Pop. Carlos Otero from Divinity Channel wrote that "Madonna has secured for life the title of Queen of Pop. He further asserted that "after 30 years of career would take another three decades to meet her influence and legacy".[150]

Mathew Donahue, one of 12 faculty members of Bowling Green State University's Pop Culture Studies program, gives lectures about Madonna in many of his music and culture classes has qualified her as the "Queen of all Media".[18] Also, she was named as the mother of "kingdom technological".[151] Madonna is also referred to as the Queen of MTV. CNN commented that MTV could stand for "Madonna Television".[152] Julían Ruíz from Spanish newspaper El Mundo said that she is our "Lady Madonna".[153]

Critic lists and polls

| Year | Critic/Publication | List | Rank | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1998 | Ladies' Home Journal | 100 Most Important Women of the 20th Century | n/a | [154] |

| 2007 | Quercus | Women Who Changed the World | n/a | [155] |

| 2010 | Time | 25 Most Powerful Women of the Past Century | n/a | [85] |

| 2012 | VH1 | 100 Greatest Women in Music | 1 | [156] |

| 2015 | The Daily Telegraph | Pop's 20 Greatest Female Artists | 1 | [157] |

| 2019 | Encyclopædia Britannica | 100 Women | n/a | [158] |

| 2019 | Time | 100 Women of the Year – 1989 | n/a | [159] |

Contradictory perspective

Professors in American Icons noted that she was not only an omnipresent figure but a polarizing one. For example, in 1993, she was the subject of the I Hate Madonna Handbook and the following year the inspirations for I Dream of Madonna.[40] Lynn Spigel noted that Madonna is a producer of cultural ambiguity and openness.[160] Rabbi Isaac Karudi —the highest authority of the Orthodox Kabbalah— described her as a "depraved cultural icon".[161] Social critic and critical theorist, Stuart Sim noted that "Madonna now attained the status of cultural icon, she is however, an extremely problematic one, as her delight in simultaneously evoking and transgressing cultural stereotypes of feminity makes her exceedingly difficult to categorize; depending on one's point of view".[162] Cultural critic Fausto Rivera Yánez from El Telégrafo said that "Madonna has labeling usurper, since much of its aesthetic and musical approach draws on religious imagery of black cultures, discourses of sexual diversity and circumstantial geopolitical contexts".[163] Maureen Orth explain her the contradiction as a cultural and social impact:[164]

"Madonna’s celebrity is unique in that it seems to depend as much on repugnance as on acceptance. Her fame frame, unlike that of most other mega-stars, rests very much on people who love to hate her—while monitoring her every move—and on others who hate to love her, as well as on the traditional adoring fans. Perhaps it’s not surprising that even academics are doing a brisk trade in 'Madonna-ology'.

American Pulitzer Prize-winning critic for The New York Times Michiko Kakutani, felt that Madonna is incredibly popular. Or: "Clearly, Madonna is not universally loved." Or: "The politics of sex and gender representations as they relate to identity has not been lost on Madonna."[19] Authors in Representing gender in cultures (2004) noted that "Madonna has been consistently denied a status of a 'real' musician and even accused of using, in a vampire-like way, fashionable musicians to update her sound".[165]

During her career, Madonna attracted the attention of family organizations, feminist "anti-porn" and religious groups worldwide with boycott and protests. Professor Bruce Forbes author of Religion and Popular Culture in America (2005) felt that "some of the most important and interesting texts in recent American culture which have overlapping concerns with liberation theologies are by Madonna".[166] Karen Fredericks from socialist newspaper Green Left Weekly questioned if does the "Madonna phenomenon" advance the cause of women's liberation within Western societies? she said that clearly, there's no point going to Madonna for help. She asserted that the artist is a commodity in a capitalist market which has been influenced, at least to some extent, by the demands of the women's movement.[121] Sociologist John Shepherd wrote that Madonna's cultural practices highlight the sadly continuing social realities of dominance and subordination.[21] In 1988, one Italian sculptor planned a statue of Madonna in Pacentro, where are from her paternal grandparents, who said "Madonna is a symbol of our children and represents a better world in the year 2000". The then mayor of the city declared: "it is absolutely untrue that the city administration of Pacentro is willing to host the statue to the singer Madonna as some maintain".[167][168]

Academic Audra Gaugler from Lehigh University advocated for Madonna, wrote that "she has faced much criticism throughout her career, but much of it is unjust. Instead of Madonna's actions eliciting criticism, they should elicit praise because she radically tries to change society by blurring the boundaries that separate different groups of people in society and she urges all people to gain power in their lives and lift themselves out of subordinate positions. Madonna blurs the boundaries that exist in society and separate people in society in two distinct ways". She noted that there exists a large band of critics that at first praised her, but then became disillusioned with her as she became more and more controversial.[22]

References

- Ana, Laglere (April 14, 2015). "9 razones que explican por qué Madonna es la Reina del Pop de todos los tiempos" [9 reasons explain why Madonna is the Queen of Pop of all time] (in Spanish). Batanga.com. pp. 1–8. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- Herman 2009, pp. 286

- von Aue, Mary (October 24, 2014). "WHY MADONNA'S UNAPOLOGETIC 'BEDTIME STORIES' IS HER MOST IMPORTANT ALBUM". Vice Magazine. Retrieved June 22, 2013.

- Robinson, Peter (March 5, 2011). "Madonna inspired modern pop stars". The Guardian. London. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- "Madonna Biography". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. 2008. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- Marcovitz, Hal (2010). Madonna: Entertainer (Women of Achievement) Library Binding – November 1, 2010. ISBN 978-1604138597.

- Jaime Anderson & Martin Kupp (2006). "Madonna – Strategy on the Dance Floor" (PDF). European School of Management and Technology (ESMT). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 29, 2015. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- Claude 2002, p. 88

- Quico, Alsedo (September 5, 2013). "Madonna = Bachar El Asad". El Mundo (in Spanish). Spain. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- T. Cole Rachel (March 2, 2015). "Pop Sovereign: A Conversation with Madonna". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- Claude 2002

- Langley, William (August 9, 2008). "Madonna, mistress of metamorphosis". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- Benson 2000, p. 241

- May 1997, pp. 169

- Tatiana, Giselle; Pérez, Rojas (November 25, 2012). "Fans esperan a Madonna" [Fans waiting for Madonna]. ElMundo (in Spanish). Colombia. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- Clúa Ginés & Pitarch 2008, pp. 81,84,90

- Strawberry Saroyan and Michelle Goldberg (October 10, 2000). "So-called Chaos". Salon. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- DeMarco, Laura (August 30, 2013). "30 years of Madonna". Cleveland. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- Kakutani, Michiko (October 21, 1992). "Books of The Times; Madonna Writes; Academics Explore Her Erotic Semiotics". The New York Times. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- Sexton, Adam, ed. (December 1992). Desperately Seeking Madonna: In Search of the Meaning of the World's Most Famous Woman (1st Printing January 1993 ed.). New York: Delta. ISBN 9780385306881.

- Shepard 2003, p. 108

- Gaugler, Audra (2000). "Madonna, an American pop icon of feminism and counter-hegemony : blurring the boundaries [sic] of race, gender, and sexuality by Audra Gaugler". Lehigh University. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- Tavana, Art (May 15, 2014). "Madonna was better than Michael Jackson". Death & Taxes. Retrieved April 14, 2015.

- Faith, Karlene (1997). Madonna, Bawdy & Soul. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9780802042088. JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctt2tv4xw#.

- Cullen 2001, p. 85

- Hall 2006, p. 51

- Aguilar Guzmán 2010, p. 88

- Jeansonne 2006, pp. 446

- Skarda, Erin (April 2, 2012). "Madonna - All-TIME Top 100 Icons in Fashion, Style and Design". Time. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- Smith-Shomade 2002, p. 162

- "Madonna: Biography of the World's Greatest Pop Singer [Kindle Edition]". Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- Cullen 2001, p. 86

- Marcus, Sara (February 3, 2012). "How Madonna liberated America". Salon. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- Claude 2002, pp. 41–43

- Annalee, Newitz (November 1993). "Madonna's Revenge". EServer.org. Archived from the original on February 28, 2014. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- Spigel & Brunsdon 2007, p. 122

- "How Madonna changed the World!". World Music Awards. August 13, 2013. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- "Impone tendencia la 'Chica material'" [Imposes trend, the Material Girl]. El Universal (in Spanish). Mexico. November 2008. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- McNair 2002, pp. 69

- Hall 2006, pp. 446

- Huang 1999, pp. 386

- "Cultural Icons, Charismatic Heroes, Representative Lives" (PDF). Heidelberg University. p. 22. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- Welsh, Alyson (April 9, 2015). "Why Madonna is still my style icon (despite the look-at-me lingerie)". The Guardian. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- "AJAS". Australasian Journal of American Studies (AJAS). 15: 60. July 1, 1996. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- Wexter, Erica (April 1998). "Reviews Madonna Ray of Light". ThirdWay. 21 (3): 28. Retrieved April 7, 2013.

- Madonna. ISBN 0752890514.

- Hack, Jefferson (2008). "Madonna: 21st Century Icon". Dazed. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

- Madonna Paperback – March 27, 2002. ISBN 1854794329.

- Madonna in Art Hardcover – December 1, 2004. 2004. ISBN 1904957005.

- Bleuzen, Anne (November 2005). Madonna Belle reliure – 18 novembre 2005. ISBN 2915957037.

- Mad for Madonna. La regina del pop (Italian) Perfect Paperback – January 1, 2011. ISBN 8876155503.

- Gutiérrez Seguro, Eduardo (February 6, 2012). "Su majestad camaleónica: Madonna" [Her Majesty chameleonic: Madonna]. Quién (in Spanish). Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- "At 50, has Madonna surpassed the Beatles?". Rolling Stone. July 6, 2011. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- "A presque 30 ans de carrière, Madonna cartonne toujours" (in French). Belgium: RTL Television (RTL Group). March 21, 2013. Archived from the original on May 17, 2013. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- Wyman, Bill (June 20, 1991). "Truth or Dare: Madonna's big lie". Chicago Reader. Wrapports. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- Busari, Stephanie (March 24, 2008). "Hey Madonna, Don't Give Up the Day Job!". CNN. Retrieved April 11, 2015.

- Blackmore & de Castro 2008, p. 496

- Regalado 2002, pp. 11

- "Madonna Crowned 'Greatest' Woman In Music". MTV. February 12, 2012. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- Sclafani, Tony (December 8, 2008). "At 50, has Madonna surpassed the Beatles?". MSNBC. Retrieved April 14, 2015.

- Barcella 2012

- Gundersen, Edna (August 17, 2008). "Pop icons at 50: Madonna". USA Today. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- "100 Greatest Artists: Madonna". Rolling Stone. Retrieved April 10, 2015.

- Stephen Thomas Erlewine. "Madonna Biography at MTV". MTV. Retrieved April 10, 2015.

- Benson 2000, pp. 231

- Fleischer, Joe (October 1998). "Hush Hush / The Monthly Dish On The Music Business". Spin. SpinMedia. 14 (10): 58. ISSN 0886-3032. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- "Madonna Key Achievements". Marquee Capital. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- Rosa, Chris (November 12, 2014). "10 Things Millennials Don't Understand About Madonna". VH1. pp. 1–4. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- Kaplan 2012, p. 32

- Forman-Brunell 2001, p. 531

- "Mujeres que cambiaron las reglas del rock" [Woman who change the rock rules]. Rolling Stone (in Spanish). Spain. April 14, 2012. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

- Vargo, Erin (January 9, 2015). "Madonna Should Not Have Apologized". Acculturated. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- Fouz-Hernández & Jarman-Ivens 2004, p. 162

- Niemietz, Brian (April 3, 2008). "Madonna Don't Preach". The New York Post. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

- Izod 2001, pp. 79

- Ganz, Caryn. "Madonna Biography". Rolling Stone. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- Metz & Benson 1999, p. 55

- Kellner, Douglas. "Culture Studies, Multiculturalism, and Media Culture by Douglas Kellner". University of California, Los Angeles. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- Watts, Mark (May 1996). "Electrifying Fragments: Madonna and Postmodern Performance". Cambridge University Press. pp. 99–107. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

- Dorenkamp 1995, p. 149

- Rettenmund, Matthew (March 15, 1995). Encyclopedia Madonnica. ISBN 9780312117825. Retrieved February 22, 2015.

Norman Mailer thinks she's our "greatest living female artist." In short, Madonna is the biggest star in the world.

- "Your comments". BBC News. November 25, 2003. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- Friskics-Warren 2006, p. 63

- Glenday, Craig (ed.). "Most Successful Female Solo Artist". Guinness Book of World Records. Archived from the original on September 4, 2004. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- Castillo, Michelle (November 18, 2010). "The 25 Most Powerful Women of the Past Century". Time. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- Wills, Kate (August 16, 2013). "Happy 55th Birthday Madonna! Here are 55 ways you changed the world". Daily Mirror. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- Pilkington, Ed (November 3, 2006). "Once upon a time". The Guardian. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- Blankenship, Mark (October 22, 2012). "My Weird Journey With Madonna's 'Sex' Book". NewNowNext.com. Archived from the original on August 31, 2013. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- Sprague, David (November 23, 1996). "New Sets Offer 'Greatest Ballads'". Billboard: 15. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- Ursprung, Stephen (May 1, 2012). "Voguing: Madonna and Cyclical Reappropriation". Smith College. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- Kane, Same (May 31, 2013). "Is Yahoo the Madonna of digital media?". United Kingdom: Wallblog (Haymarket Media Group). Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- Victor Lenore & Irene G. Rubio (June 26, 2012). "Madonna: ¿icono feminista o tótem consumista?" [Madonna: feminist icon or consumerist totem?]. Periódico Diagonal (in Spanish). Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- Joshua Rich (November 20, 1998). "Madonna Banned". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

Madonna helped make MTV as much as [MTV] helped make her, says Mark Bego, author of Madonna: Blonde Ambition..

- Michael, Mick St (1999). Madonna: In Her Own Words (In Their Own Words) Paperback – December 31, 1990. ISBN 0711977348.

- Jonas, Liana. "Ray of Light - Madonna". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- O'Brien 2002, pp. 485–489

- Harrison 2011, p. 4

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Madonna - Madonna review". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

- Hammer & Kellner 2009, pp. 502–503

- Clerk 2002, p. 44

- "Tzfat, The City of Kabbalah". Safed. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- "The cultural significance of Madonna". UK Essays. August 5, 2005. Archived from the original on November 13, 2016. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- Rogelio, Segoviano (November 18, 2012). "Todos Quieren Con Madonna" [Everybody wants with Madonna]. El Universal (in Spanish). Mexico. Archived from the original on February 23, 2015. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- Benstock & Ferriss 1994, p. 172

- Claude 2002, pp. 37

- Benstock & Ferriss 1994, p. 176

- "Madonna's Fashion Evolution: Her Most Iconic Looks". Billboard. March 22, 2012. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- Oliver, Dana (August 16, 2013). "Why Madonna Is The Ultimate Style Chameleon". HuffPost. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- Chloe, Wyma. "Madonna a los 55 años de edad: ¿existe otro momento mejor para examinar sus contribuciones a la moda y el feminismo?" [Madonna to 55 years: Is there another better moment to examine her contributions to fashion and feminism?] (in Spanish). Louise Blouin Media. Archived from the original on September 4, 2013. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- Robins, Cynthia (September 2, 2001). "The Material Girl Madonna's fashion sense has". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- Codinha, Alessandra (April 7, 2015). "Exclusive! Madonna on the Look of Her New Ghosttown video". Vogue. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- Jhally 2006, p. 194

- Paglia, Camille (December 14, 1990). "Madonna – Finally, A Real Feminist". The New York Times. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- Eisenbud & Leigh-Kile 1999, p. 15

- Barcella, Laura (March 6, 2012). Madonna and Me: Women Writers on the Queen of Pop Paperback – March 6, 2012. ISBN 978-1593764296.

- Khaleeli, Homa (March 8, 2011). "Madonna". The Guardian. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- "Madonna". New Internationalist. August 5, 1991. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- Gregg, McDonogh & Wong

- Smith 2011, pp. 119

- Klosterman 2003

- Fredericks, Karen (October 22, 1992). "and ain't i a woman?: Madonna: sexual revolutionary?". Green Left Weekly (77). Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- Gaard, Greta (1992). "The Laugh of Madonna: Censorship and Oppositional Discourse". The Journal of the Midwest Modern Language Association. 25 (1): 41–46. doi:10.2307/1315073. ISSN 0742-5562. JSTOR 1315073.

- Geczy & Karaminas 2013, p. 38

- Boteach 2005, p. 110

- "Madonna, vigente a los 50" [Madonna, still got it at 50] (in Spanish). Cambio.com (AOL). November 2, 2008. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved February 21, 2013.

- Davidson 2003, p. 100

- "S&M offers a safe haven for ex "classy" topless bars". New York. 27 (47): 40. November 18, 1994. ISSN 0028-7369.

- Bachmann 2002, p. 77

- McNair 2012, p. 267

- Karpel, Ari (February 2, 2012). "Madonna: The Truth Is She Never Left You". The Advocate. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- "Madonna". New Statesman. 129 (4493–4505): 46. 2000. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- Sarracino & Scott 2002, p. 93

- "Your Letters continued". Out. 13 (7–12): 178. 2005. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- Peraino 2005, p. 143

- Hopkins, Alex (August 11, 2011). "Is Madonna still the ultimate gay icon?". Time Out. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- Goss 2002, p. 178

- Whiteley 2013, p. 275

- O'Brien 2007, p. 27

- Appignanesi & Garratt 2014

- Genz & Brabon 2009, p. 118

- "Review: Madonna Style". M. November 12, 2012. Archived from the original on May 3, 2013. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- Pham, Duyen (January 9, 2015). "MADONNA: REBEL WITH A CAUSE?". Rutgers University. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- Kellner 1995, p. 263

- "Becks: Greatest Pop Icon Of All Time". United Kingdom: Sky News. November 12, 2003. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- Langley, William (September 3, 2011). "Clear the set – Madonna wants to express herself". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- "As 50 cantoras que nunca serão esquecidas" (in Portuguese). Brazil: Yahoo!. Archived from the original on February 4, 2010. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- "Madonna: The World's Biggest Star Is Just Hitting Her Stride". HuffPost. October 10, 2014. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- "Madonna". Qué Pasa (1291–1303). 1996. p. 513. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- McGee, Alan (August 20, 2008). "Madonna Pop Art". The Guardian. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- Otero, Carlos (September 3, 2012). "Madonna se aburguesa: sus polémicas ya no son lo que eran" (in Spanish). Spain: Divinity TV. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- Lysloff & Gay 2003, pp. 189–192

- "MTV changed the music industry on August 1, 1981". CNN. July 31, 1998. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- Ruíz, Julían (November 19, 2013). "Santa Madonna, 'ora pro nobis'" [Holy Madonna, 'ora pro nobis']. El Mundo (in Spanish). Spain. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

- Edwards, Vicky (November 8, 1998). "Women's Works Get Their Words' Worth". Chicago Tribune. Tribune Company. Archived from the original on May 4, 2012. Retrieved September 7, 2011.

- Horton, Ros (January 2007). Women Who Changed the World. ISBN 9781847240262.

- Graham, Mark (February 13, 2012). "VH1's 100 Greatest Women in Music". VH1. Viacom. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- "Pop's 20 greatest female artists". The Daily Telegraph. August 7, 2015. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. "100 Women". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- Cooper, Brittney. "Madonna: TIME 100 Women of the Year - 1989: Madonna". Time. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- Spigel 2007, pp. 123

- Vidal, Jose Manuel. "Los pecados que ya no cometerás". El Mundo (in Spanish). Spain. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- Sim 2013, pp. 310

- Rivera Yánez, Fausto (September 16, 2013). "Madonna: 'Quiero controlar el mundo'" [Madonna: 'I want to control the world']. El Telégrafo (in Spanish). Ecuador. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- Orth, Maureen (October 1992). "Madonna in Wonderland". Vanity Fair. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- H. Oleksy, Elżbieta; Rydzewska, Joanna (2004). Representing gender in cultures. Peter Lang. p. 134. ISBN 3631506678. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- Forbes 2005, pp. 75

- W. Speers (January 6, 1988). "Statue Of Madonna Is Debated". Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- "Statue of Madonna won't stand in Italy". The Gettysburg Times. Associated Press (AP). January 8, 1988. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

Bibliography

- Appignanesi, Richard; Garratt, Chris (2014). Introducing Postmodernism: A Graphic Guide. Icon Books. ISBN 978-1848317604.

- Aguilar Guzmán, Marcela (2010). Domadores de historias. Conversaciones con grandes cronistas de América Latina (in Spanish). RIL Editores. ISBN 978-956-284-782-7.

- Barcella, Laura (2012). Madonna and Me: Women Writers on the Queen of Pop. Soft Skull Press. ISBN 978-1-59376-475-3.

- Benson, Carol; Metz, Allen (1999). The Madonna Companion: Two Decades of Commentary. Music Sales Group. ISBN 0-8256-7194-9.

- Benson, Carol (2000). Madonna the Companion Two Decades of Commentary. Music Sales Group. ISBN 0825671949.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Benstock, Shari; Ferriss, Suzanne (1994). Oh Fashion. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0813520339.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Boteach, Shmuel (2005). Hating women: America's hostile campaign against the fairer sex. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-078122-4.

- Blackmore, Hazel; de Castro, Rafael Fernández (2008). ¿Qué es Estados Unidos? (in Spanish). Fondo de Cultura Economica. ISBN 978-968-16-8461-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Claude, Guilbert-Georges (2002). Madonna As Postmodern Myth: How One Star's Self-Construction Rewrites Sex, Gender, Hollywood and the American Dream. McFarland & Company. ISBN 0786414081.

- Clerk, Garol (2002). Madonnastyle. Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-7119-8874-9.

- Clúa Ginés, Isabel; Pitarch, Pau (2008). Pasen y vean. Estudios culturales (in Spanish). Open University of Catalonia. ISBN 978-84-9788-726-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cullen, Jim (2001). Restless in the Promised Land: Catholics and the American Dream : Portraits of a Spiritual Quest from the Time of the Puritans to the Present. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 1580510930.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davidson, D. Kirk (2003). Selling Sin: The Marketing of Socially Unacceptable Products. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 156720645X.

- Dorenkamp, Angela G (1995). Images of women in American popular culture. Harcourt. ISBN 0155010131.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eisenbud, Jule; Leigh-Kile, Donna (1999). Sex Symbols. Random House. ISBN 188331951X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fiske, John (1989). Reading the popular. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-07875-X.

- Forbes, Bruce David (2005). Religion and Popular Culture in America. University of California Press. ISBN 0520246896.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Forman-Brunell, Miriam (2001). Girlhood in America: A-G. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1576072061.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fouz-Hernández, Santiago; Jarman-Ivens, Freya (2004). Madonna's Drowned Worlds. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 0-7546-3372-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Friskics-Warren, Bill (2006). I'll Take You There: Pop Music and the Urge for Transcendence. A&C Black. ISBN 0826419216.

- Granés, Carlos (2015). La invención del paraíso: El Living Theatre y el arte de la osadía (in Spanish). Penguin Random House. ISBN 978-0748635801.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Genz, Stéphanie; Brabon, Benjamin A. (2009). Postfemenism: Cultural Texts and Theories. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0748635801.

- Gregg, Robert; McDonogh, Gary W.; H. Wong, Cindy (2001). Encyclopedia of Contemporary American Culture. Routledge. ISBN 9780415161619.

- Goss, Robert (2002). Queering Christ: Beyond Jesus Acted Up. Pilgrim Press. ISBN 0829814981.

- Geczy, Adam; Karaminas, Vicki (2013). Queer Style. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1472535344.

- Hammer, Thomas; Kellner, Douglas (2009). Media/cultural Studies: Critical Approaches. Peter Lang. ISBN 9780820495262.

- Hall, Dennis (2006). American Icons. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0313027676.

- Harrison, Thomas (2011). Music of the 1990s. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0313379420.

- Herman, Gary (2009). Historia trágica del rock (in Spanish). Ediciones Robinbook. ISBN 978-8496924529.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Huang, Hao (1999). Music in the 20th Century, Volume 2. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 0765680122.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Izod, John (2011). Myth, Mind and the Screen: Understanding the Heroes of Our Time. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521796866.

- Jeansonne, Glen (2006). A Time of Paradox: America Since 1890. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0742533778.

- Jhally, Sut (2006). The Spectacle of Accumulation: Essays in Culture, Media, And Politics. Peter Lang. ISBN 0-8204-7904-7.

- Kaplan, Arie (2012). American Pop: Hit Makers, Superstars, and Dance Revolutionaries. Twenty-First Century Book. ISBN 978-1467701488.

- Kellner, Douglas (1995). Media Culture: Cultural Studies, Identity, and Politics Between the Modern and the Postmodern. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-10570-6.

- Klosterman, Chuck (2003). Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs. Routledge. ISBN 0-7432-3600-9.

- Landrum, Gene N. (2007). Paranoia & Power: Fear & Fame of Entertainment Icons. Morgan James Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60037-273-5.

- Lysloff, Rene T.; Gay, Leslie C. (2003). Music and Technoculture. Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 0819565148.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- May, John R. (1997). The New Image of Religious Film. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 1-55612-761-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McNair, Brian (2002). Striptease Culture: Sex, Media and the Democratisation of Desire. Routledge. ISBN 9781134559473.

- O'Brien, Lucy (2007). Madonna: Like an Icon. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-593-05547-2.

- Peraino, Judith A. (2005). Listening to the Sirens: Musical Technologies of Queer Identity from Homer to Hedwig. University of California Press. ISBN 0520921747.

- Regalado, Jojo (2002). Pietro. iUniverse. ISBN 0595223524.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sarracino, Carmine; Scott, Kevin M. (2008). The Porning of America: The Rise of Porn Culture, what it Means, and where We Go from Here. Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0807061534.

- Shepard, John (2003). Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World: Performance and production. Volume II. A&C Black. ISBN 0826463215.

- Sim, Stuart (2013). The Routledge Companion to Postmodernism. Routledge. ISBN 978-1134545698.

- Smith, Courtney E. (2011). Record Collecting for Girls: Unleashing Your Inner Music Nerd, One Album at a Time. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0547502236.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith-Shomade, Beretta E. (2002). Shaded Lives: African-American Women and Television. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0813531055.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spigel, Lynn; Brunsdon, Charlotte (2007). Feminist Television Criticism: A Reader. McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-0335225453.

- Whiteley, Sheila (2011). Sexing the Groove: Popular Music and Gender. Routledge. ISBN 978-1135105129.