Demyelinating disease

A demyelinating disease is any disease of the nervous system in which the myelin sheath of neurons is damaged.[1] This damage impairs the conduction of signals in the affected nerves. In turn, the reduction in conduction ability causes deficiency in sensation, movement, cognition, or other functions depending on which nerves are involved.

| Demyelinating disease | |

|---|---|

| |

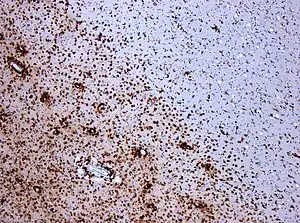

| Photomicrograph of a demyelinating MS-lesion: Immunohistochemical staining for CD68 highlights numerous macrophages (brown). Original magnification 10×. | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

Demyelinating diseases can be caused by genetics, infectious agents, autoimmune reactions, and other unknown factors. Proposed causes for demyelination include genetics and environmental factors such as being triggered by a viral infection or chemical exposure. Organophosphate poisoning by commercial insecticides such as sheep dip, weed killers, and flea treatment preparations for pets, can also result in nerve demyelination.[2] Chronic neuroleptic exposure may cause demyelination.[3] Vitamin B12 deficiency may also result in dysmyelination.[4][5]

Demyelinating diseases are traditionally classified in two kinds: demyelinating myelinoclastic diseases and demyelinating leukodystrophic diseases. In the first group, a normal and healthy myelin is destroyed by a toxic, chemical, or autoimmune substance. In the second group, myelin is abnormal and degenerates.[6] The second group was denominated dysmyelinating diseases by Poser.[7]

In the most well known example of demyelinating disease, multiple sclerosis, evidence has shown that the body's own immune system is at least partially responsible. Acquired immune system cells called T-cells are known to be present at the site of lesions. Other immune-system cells called macrophages (and possibly mast cells) also contribute to the damage.[8]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms and signs that present in demyelinating diseases are different for each condition. These symptoms and signs can present in a person with a demyelinating disease:[9]

|

|

Evolutionary considerations

The role of prolonged cortical myelination in human evolution has been implicated as a contributing factor in some cases of demyelinating disease. Unlike other primates, humans exhibit a unique pattern of postpubertal myelination, which may contribute to the development of psychiatric disorders and neurodegenerative diseases that present in early adulthood and beyond. The extended period of cortical myelination in humans may allow greater opportunity for disruption in myelination, resulting in the onset of demyelinating disease.[10] Furthermore, humans have significantly greater prefrontal white matter volume than other primate species, which implies greater myelin density.[11] Increased myelin density in humans as a result of a prolonged myelination may, therefore, structure risk for myelin degeneration and dysfunction. Evolutionary considerations for the role of prolonged cortical myelination as a risk factor for demyelinating disease are particularly pertinent given that genetics and autoimmune deficiency hypotheses fail to explain many cases of demyelinating disease. As has been argued, diseases such as multiple sclerosis cannot be accounted for by autoimmune deficiency alone, but strongly imply the influence of flawed developmental processes in disease pathogenesis.[12] Therefore, the role of the human-specific prolonged period of cortical myelination is an important evolutionary consideration in the pathogenesis of demyelinating disease.

Diagnosis

Various methods/techniques are used to diagnose demyelinating diseases:

- Exclusion of other conditions that have overlapping symptoms[13]

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a medical imaging technique used in radiology to visualize internal structures of the body in detail. MRI makes use of the property of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) to image nuclei of atoms inside the body. This method is reliable because MRIs assess changes in proton density. "Spots" can occur as a result of changes in brain water content.[13]:113

- Evoked potential is an electrical potential recorded from the nervous system following the presentation of a stimulus as detected by electroencephalography (EEG), electromyography (EMG), or other electrophysiological recording method.[13]:117

- Cerebrospinal fluid analysis (CSF) can be extremely beneficial in the diagnosis of central nervous system infections. A CSF culture examination may yield the microorganism that caused the infection.[13]

- Quantitative proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) is a noninvasive analytical technique that has been used to study metabolic changes in brain tumors, strokes, seizure disorders, Alzheimer's disease, depression, and other diseases affecting the brain. It has also been used to study the metabolism of other organs such as muscles.[13]:309

- Diagnostic criteria refers to a specific combination of signs, symptoms, and test results that the clinician uses in an attempt to determine the correct diagnosis.[13]:320

- Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) uses a pulse sequence to suppress cerebrospinal fluid and show lesions more clearly, and is used for example in multiple sclerosis evaluation.

Types

Demyelinating diseases can be divided in those affecting the central nervous system (CNS) and those affecting the peripheral nervous system (PNS). They can also be classified by the presence or absence of inflammation. Finally, a division may be made based on the underlying cause of demyelination: the disease process can be demyelinating myelinoclastic, wherein myelin is destroyed; or dysmyelinating leukodystrophic, wherein myelin is abnormal and degenerative.

CNS

The demyelinating disorders of the central nervous system include:

- Myelinoclastic or demyelinating disorders:

- Typical forms of multiple sclerosis

- Neuromyelitis optica, or Devic's disease

- Idiopathic inflammatory demyelinating diseases

- Leukodystrophic or dysmyelinating disorders:

- CNS neuropathies such as those produced by vitamin B12 deficiency

- Central pontine myelinolysis

- Myelopathies such as tabes dorsalis (syphilitic myelopathy)

- Leukoencephalopathies such as progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

- Leukodystrophies

The myelinoclastic disorders are typically associated with symptoms such as optic neuritis and transverse myelitis, because the demyelinating inflammation can affect the optic nerve or spinal cord. Many are idiopathic. Both myelinoclastic and leukodystrophic modes of disease may result in lesional demyelinations of the central nervous system.

PNS

The demyelinating diseases of the peripheral nervous system include:

- Guillain–Barré syndrome and its chronic counterpart, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy

- Anti-MAG peripheral neuropathy

- Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease and its counterpart Hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsy

- Copper deficiency-associated conditions (peripheral neuropathy, myelopathy, and rarely optic neuropathy)

- Progressive inflammatory neuropathy

Treatment

Treatments are patient-specific and depend on the symptoms that present with the disorder, as well as the progression of the condition. Improvements to the patient's life may be accomplished through the management of symptoms or slowing of the rate of demyelination. Treatment can include medication, lifestyle changes (i.e. smoking cessation, increased rest, and dietary changes), counselling, relaxation, physical exercise, patient education, and in some cases, deep brain thalamic stimulation (to ameliorate tremors).[13]:227–248

Prognosis

Prognosis depends on the condition itself. Some conditions such as MS depend on the subtype of the disease and various attributes of the patient such as age, sex, initial symptoms, and the degree of disability the patient experiences.[14] Life expectancy in MS patients is 5 to 10 years lower than unaffected people.[15] MS is an inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS) that develops in genetically susceptible individuals after exposure to unknown environmental trigger(s). The bases for MS are unknown but are strongly suspected to involve immune reactions against autoantigens, particularly myelin proteins. The most accepted hypothesis is that dialogue between T-cell receptors and myelin antigens leads to an immune attack on the myelin-oligodendrocyte complex. These interactions between active T cells and myelin antigens provoke a massive destructive inflammatory response and promote continuing proliferation of T and B cells and macrophage activation, which sustains secretion of inflammatory mediators.[16] Other conditions such as central pontine myelinolysis have about a third of patients recover and the other two-thirds experience varying degrees of disability.[17] In some cases, such as transverse myelitis, the patient can begin recovery as early as 2 to 12 weeks after the onset of the condition.

Epidemiology

Incidence of demyelinating diseases varies by disorder. Some conditions, such as tabes dorsalis appear predominantly in males and begin in midlife. Optic neuritis, though, occurs preferentially in females typically between the ages of 30 and 35.[18] Other conditions such as multiple sclerosis vary in prevalence depending on the country and population.[19] This condition can appear in children and adults.[15]

Research

Much of the research conducted on demyelinating diseases is targeted towards discovering the mechanisms by which these disorders function in an attempt to develop therapies and treatments for individuals affected by these conditions. For example, proteomics has revealed several proteins which contribute to the pathophysiology of demyelinating diseases.[20]

For example, COX-2 has been implicated in oligodendrocyte death in animal models of demyelination.[21] The presence of myelin debris has been correlated with damaging inflammation as well as poor regeneration, due to the presence of inhibitory myelin components.[22][23]

N-cadherin is expressed in regions of active remyelination and may play an important role in generating a local environment conducive to remyelination.[24] N-cadherin agonists have been identified and observed to stimulate neurite growth and cell migration, key aspects of promoting axon growth and remyelination after injury or disease.[25]

Immunomodulatory drugs such as fingolimod have been shown to reduce immune-mediated damage to the CNS, preventing further damage in patients with MS. The drug targets the role of macrophages in disease progression.[26][27]

Manipulating thyroid hormone levels may become a viable strategy to promote remyelination and prevent irreversible damage in MS patients.[28] It has also been shown that intranasal administration of apotransferrin (aTf) can protect myelin and induce remyelination.[29] Finally, electrical stimulation which activates neural stem cells may provide a method by which regions of demyelination can be repaired.[30]

In other animals

Demyelinating diseases/disorders have been found worldwide in various animals. Some of these animals include mice, pigs, cattle, hamsters, rats, sheep, Siamese kittens, and a number of dog breeds (including Chow Chow, Springer Spaniel, Dalmatian, Samoyed, Golden Retriever, Lurcher, Bernese Mountain Dog, Vizsla, Weimaraner, Australian Silky Terrier, and mixed breeds).[31][32]

Another notable animal found able to contract a demyelinating disease is the northern fur seal. Ziggy Star, a female northern fur seal, was treated at the Marine Mammal Center beginning in March 2014 [33] and was noted as the first reported case of such disease in a marine mammal. She was later transported to Mystic Aquarium & Institute for Exploration for lifelong care as an ambassador to the public.[34]

See also

- Multiple sclerosis borderline

- The Lesion Project (multiple sclerosis)

- The Myelin Project

- Myelin Repair Foundation

References

- "demyelinating disease" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- Lotti M, Moretto A (2005). "Organophosphate-induced delayed polyneuropathy". Toxicol Rev. 24 (1): 37–49. doi:10.2165/00139709-200524010-00003. PMID 16042503.

- Konopaske GT; Dorph-Petersen KA; Sweet RA; et al. (April 2008). "Effect of chronic antipsychotic exposure on astrocyte and oligodendrocyte numbers in macaque monkeys". Biol. Psychiatry. 63 (8): 759–65. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.08.018. PMC 2386415. PMID 17945195.

- Agadi S, Quach MM, Haneef Z (2013). "Vitamin-responsive epileptic encephalopathies in children". Epilepsy Res Treat. 2013: 510529. doi:10.1155/2013/510529. PMC 3745849. PMID 23984056.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Yoganathan S, Varman M, Oommen SP, Thomas M (2017). "A Tale of Treatable Infantile Neuroregression and Diagnostic Dilemma with Glutaric Aciduria Type I." J Pediatr Neurosci. 12 (4): 356–359. doi:10.4103/jpn.JPN_35_17. PMC 5890558. PMID 29675077.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Fernández O.; Fernández V.E.; Guerrero M. (2015). "Demyelinating diseases of the central nervous system". Medicine. 11 (77): 4601–4609. doi:10.1016/j.med.2015.04.001.

- Poser C. M. (1961). "Leukodystrophy and the Concept of Dysmyelination". Arch Neurol. 4 (3): 323–332. doi:10.1001/archneur.1961.00450090089013. PMID 13737358.

- Laetoli (January 2008). "Demyelination". Archived from the original on 2012-07-28.

- "Symptoms of Demyelinating Disorders - Right Diagnosis." Right Diagnosis. Right Diagnosis, 01 Feb 2012. Web. 24 Sep 2012

- Miller Daniel J (2012). "Prolonged Myelination in Human Neocortical Evolution". PNAS. 109 (41): 16480–16485. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10916480M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1117943109. PMC 3478650. PMID 23012402.

- Schoenemann, Thomas P.; Sheehan Michael J.; Glotzer L. Daniel (2005). "Prefrontal White Matter Volume Is Disproportionately Larger in Humans than in Other Primates". Nature Neuroscience. 8 (2): 242–52. doi:10.1038/nn1394. PMID 15665874.

- Chaudhuri Abhijit (2013). "Multiple Sclerosis Is Primarily a Neurodegenerative Disease". J Neural Transm. 120 (10): 1463–466. doi:10.1007/s00702-013-1080-3. PMID 23982272.

- Freedman, Mark S (2005). Advances in Neurology Volume 98: Multiple Sclerosis and Demyelinating Diseases. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 112. ISBN 0781751705.

- Weinshenker BG (1994). "Natural history of multiple sclerosis". Ann. Neurol. 36 (Suppl): S6–11. doi:10.1002/ana.410360704. PMID 8017890.

- Compston A, Coles A (October 2008). "Multiple sclerosis". Lancet. 372 (9648): 1502–17. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61620-7. PMID 18970977.

- Minegar, Alireza (2003). "Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption in Multiple Sclerosis". Multiple Sclerosis Journal. Sage Journals. 9 (6): 540–549. doi:10.1191/1352458503ms965oa. PMID 14664465.

- Abbott R, Silber E, Felber J, Ekpo E (October 2005). "Osmotic demyelination syndrome". BMJ. 331 (7520): 829–30. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7520.829. PMC 1246086. PMID 16210283.

- Rodriguez M, Siva A, Cross SA, O'Brien PC, Kurland LT (1995). "Optic neuritis: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota". Neurology. 45 (2): 244–50. doi:10.1212/WNL.45.2.244. PMID 7854520.

- Rosati G (April 2001). "The prevalence of multiple sclerosis in the world: an update". Neurol. Sci. 22 (2): 117–39. doi:10.1007/s100720170011. PMID 11603614.

- Newcombe, J.; Eriksson, B.; Ottervald, J.; Yang, Y.; Franzen, B. (2005). "Extraction and proteomic analysis of proteins from normal and multiple sclerosis postmortem brain". Journal of Chromatography B. 815 (1–2): 119–202. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.10.073. PMID 15652809.

- Palumbo, S.; Toscano, C.D.; Parente, L.; Weigert, R.; Bosetti, F. (2012). "The cyclooxygenase-2 pathway via the pge₂ ep2 receptor contributes to oligodendrocytes apoptosis in cuprizone-induced demyelination". Journal of Neurochemistry. 121 (3): 418–427. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07363.x. PMC 3220805. PMID 21699540.

- Clarner, T.; Diederichs, F.; Berger, K.; Denecke, B.; Gan, L.; Van Der Valk, P.; Beyer, C.; Amor, S.; Kipp, M. (2012). "Myelin debris regulates inflammatory responses in an experimental demyelination animal model and multiple sclerosis lesions". Glia. 60 (10): 1468–1480. doi:10.1002/glia.22367. PMID 22689449.

- Podbielska M, Banik NL, Kurowska E, Hogan EL (2013). "Myelin recovery in multiple sclerosis: the challenge of remyelination". Brain Sci. 3 (4): 1282–324. doi:10.3390/brainsci3031282. PMC 4061877. PMID 24961530.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Hochmeister, S.; Romauch, M; Bauer, J; Seifert-Held, T; Weissert, R; Linington, C; Hurtung, H.P.; Fazekas, F; Storch, M.K. (2012). "Re-expression of n-cadherin in remyelinating lesions of experimental inflammatory demyelination". Experimental Neurology. 237 (1): 70–77. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.06.010. PMID 22735489.

- Burden-Gulley, S.M.; Gates, T.J.; Craig, S.E.L.; Gupta, M.; Brady-Kalnay, S.M. (2010). "Stimulation of n-cadherin-dependent neurite outgrowth by small molecule peptide mimetic agonists of the n-cadherin hav motif". Peptides. 31 (5): 842–849. doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2010.02.002. PMID 20153391.

- Gasperini, C.; Ruggieri, S. (2012). "Development of oral agent in the treatment of multiple sclerosis- how the first available oral therapy, fingolimod will change therapeutic paradigm approach". Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 6: 175–186. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S8927. PMC 3414371. PMID 22888218.

- Ransohoff, R.M.; Hower, C.L.; Rodriquez, M. (2005). "Growth factor treatment of demyelinating disease- at last, a leap into the light". Trends in Immunology. 23 (11): 512–516. doi:10.1016/S1471-4906(02)02321-9. PMID 12401395.

- Silverstroff, L.; Batucci, S.; Pasquini, J.; Franco, P. (2012). "Cuprizone-induced demyelination in the rat cerebral cortex and thyroid hormone effects on cortical remyelination". Experimental Neurology. 235 (1): 357–367. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.02.018. PMID 22421533.

- Clausi, M.G.; Paez, P.M.; Campagnoni, A.T.; Pasquini, L.A.; Pasquini, J.M.; Ahmadiani, A. (2012). "Intranasal administration of atf protects and repairs the neonatal white matter after a cerebral hypoxic-ischemic event". Glia. 60 (10): 1540–1554. doi:10.1002/glia.22374. PMID 22736466.

- Sherafat, M.A.; Heibatollahi, M.; Mongabadi, S.; Moradi, F.; Javan, M.; Ahmadiani, A. (2012). "Electromagnetic field stimulation potentiates endogenous myelin repair by recruiting subventricular neural stem cells in an experimental model of white matter demyelination". Journal of Molecular Neuroscience. 48 (1): 144–153. doi:10.1007/s12031-012-9791-8. PMID 22588976.

- Merck Sharp; Dohme Corp (2011). "The Merck Veterinary Manual – Demyelinating Disorders: Introduction". Merck Veterinary Manual. Archived from the original on 2010-12-19. Retrieved 2012-10-30.

- "Johnson RT. DEMYELINATING DISEASES. In: Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Microbial Threats; Knobler SL, O'Connor S, Lemon SM, et al., editors. The Infectious Etiology of Chronic Diseases: Defining the Relationship, Enhancing the Research, and Mitigating the Effects: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US)". NCBI. 2004. Retrieved 2012-10-30.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-10-25. Retrieved 2016-10-25.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Ziggy Star has a Neurologic Condition". The Marine Mammal Center. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

External links

| Classification |

|---|