Edom

Edom (/ˈiːdəm/;[1][2] Edomite: 𐤀𐤃𐤌 ’Edām; Hebrew: אֱדוֹם ʼÉḏōm, lit.: "red"; Akkadian: 𒌑𒁺𒈠𒀀𒀀 Uduma; Syriac: ܐܕܘܡ Arabic:ادوم Adūm) was an ancient kingdom in Transjordan located between Moab to the northeast, the Arabah to the west and the Arabian Desert to the south and east.[3] Most of its former territory is now divided between Israel and Jordan. Edom appears in written sources relating to the late Bronze Age and to the Iron Age in the Levant, such as the Hebrew Bible and Egyptian and Mesopotamian records.

Kingdom of Edom 𐤀𐤃𐤌 | |

|---|---|

| c. 13th century BC–c. 125 BC | |

| Status | Monarchy |

| Capital | Bozrah |

| Demonym(s) | Edomites; later, via Greek: Idumaeans |

| History | |

• Established | c. 13th century BC |

• Conquered by the Hasmonean dynasty | c. 125 BC |

| Today part of | |

| Tanakh |

|---|

|

Edom and Idumea are two related but distinct terms which are both related to a historically-contiguous population but two separate, if adjacent, territories which were occupied by the Edomites/Idumeans in different periods of their history. The Edomites first established a kingdom ("Edom") in the southern area of modern-day Jordan and later migrated into the southern parts of the Kingdom of Judah ("Idumea", or modern-day southern Israel/Negev) when Judah was first weakened and then destroyed by the Babylonians, in the 6th century BC.[4]

Edom is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible and it is also mentioned in a list of the Egyptian pharaoh Seti I from c. 1215 BC as well as in the chronicle of a campaign by Ramesses III (r. 1186–1155 BC).[3] The Edomites, who have been archaeologically identified, were a Semitic people who probably arrived in the region around the 14th century BC.[3] Archaeological investigation showed that the country flourished between the 13th and the 8th century BC and was destroyed after a period of decline in the 6th century BC by the Babylonians.[3] After the loss of the kingdom, the Edomites were pushed westward towards southern Judah by nomadic tribes coming from the east; among them were the Nabataeans, who first appeared in the historical annals of the 4th century BC and already established their own kingdom in what used to be Edom, by the first half of the 2nd century BC.[3] More recent excavations show that the process of Edomite settlement in the southern parts of the Kingdom of Judah and parts of the Negev down to Timna had started already before the destruction of the kingdom by Nebuchadnezzar II in 587/86 BC, both by peaceful penetration and by military means and taking advantage of the already-weakened state of Judah.[5][6]

Once pushed out of their territory, the Edomites settled during the Persian period in an area comprising the southern hills of Judea down to the area north of Be'er Sheva.[7] The people appear under a Greek form of their old name, as Idumeans or Idumaeans, and their new territory was called Idumea or Idumaea (Greek: Ἰδουμαία, Idoumaía; Latin: Idūmaea), a term that was used in New Testament times.[8][9]

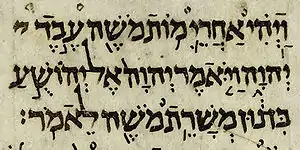

Name of Edom in the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew word Edom means "red", and the Hebrew Bible relates it to the name of its founder, Esau, the elder son of the Hebrew patriarch Isaac, because he was born "red all over".[10] As a young adult, he sold his birthright to his brother Jacob for "red pottage".[11] The Tanakh describes the Edomites as descendants of Esau.[12]

Archaeology

| The name 'Idumi' transliterated 'jdwmj' which was translated into "Edom"[13] in hieroglyphs |

|---|

The Edomites may have been connected with the Shasu and Shutu, nomadic raiders mentioned in Egyptian sources. Indeed, a letter from an Egyptian scribe at a border fortress in the Wadi Tumilat during the reign of Merneptah reports movement of nomadic "shasu-tribes of Edom" to watering holes in Egyptian territory.[14] The earliest Iron Age settlements—possibly copper mining camps—date to the 9th century BC. Settlement intensified by the late 8th century BC and the main sites so far excavated have been dated between the 8th and 6th centuries BC. The last unambiguous reference to Edom is an Assyrian inscription of 667 BC; it has thus been unclear when, how and why Edom ceased to exist as a state, although many scholars point to scriptural references in the Bible, specifically the historical Book of Obadiah, to explain this fact.[15]

Edom is mentioned in Assyrian cuneiform inscriptions in the form "Udumi" (𒌑𒁺𒈪) or "Udumu" (𒌑𒁺𒈬); three of its kings are known from the same source: Ḳaus-malaka at the time of Tiglath-pileser III (c. 745 BC), Malik-rammu at the time of Sennacherib (c. 705 BC), and Ḳaus-gabri at the time of Esarhaddon (c. 680 BC). According to the Egyptian inscriptions, the "Aduma" at times extended their possessions to the borders of Egypt.[16] After the conquest of Judah by the Babylonians, Edomites settled in the region of Hebron. They prospered in this new country, called by the Greeks and Romans "Idumaea" or "Idumea", for more than four centuries.[17] Strabo, writing around the time of Jesus, held that the Idumaeans, whom he identified as of Nabataean origin, constituted the majority of the population of Western Judea, where they commingled with the Judaeans and adopted their customs.[18] A view shared also by some modern scholarly works which consider Idumaeans as of Arab or Nabataean origins.[19][20][21][22]

The existence of the Kingdom of Edom was proved by archaeologists led by Ezra Ben-Yosef and Tom Levy, by using a methodology called the punctuated equilibrium model in 2019. Archaeologists mainly took copper samples from Timna Valley and Faynan in Jordan’s Arava valley dated to 1300-800 BC. According to the results of the analysis, the researchers thought that Pharaoh Shoshenk I of Egypt (the Biblical "Shishak"), who attacked Jerusalem in the 10th century BC, encouraged the trade and production of copper instead of destroying the region. Tel Aviv University professor Ben Yosef stated "Our new findings contradict the view of many archaeologists that the Arava was populated by a loose alliance of tribes, and they’re consistent with the biblical story that there was an Edomite kingdom here."[23][24][25]

Hebrew Bible

The Edomites' original country, according to the Hebrew Bible, stretched from the Sinai peninsula as far as Kadesh Barnea. It reached as far south as Eilat, which was the seaport of Edom.[26] On the north of Edom was the territory of Moab.[27] The boundary between Moab and Edom was the brook of Zered.[28] The ancient capital of Edom was Bozrah.[29] According to Genesis, Esau's descendants settled in the land after they had displaced the Horites. It was also called the land of Seir; Mount Seir appears to have been strongly identified with them and may have been a cultic site. In the time of Amaziah (838 BC), Sela|Selah (Petra) was its principal stronghold,[30] Eilat and Ezion-geber its seaports.[31]

Genesis 36 lists the kings of Edom:

These are the kings who ruled in the land of Edom before a king ruled the children of Israel. And Bela ben Beor ruled in Edom, and the name of his city was Dinhabah. And Bela died, and Jobab ben Zerah from Bozrah ruled in his place. And Jobab died, and Husham of the land of Temani ruled in his place. And Husham died, and Hadad ben Bedad, who struck Midian in the field of Moab, ruled in his place, and the name of his city was Avith. And Hadad died, and Samlah of Masrekah ruled in his place. And Samlah died, and Saul of Rehoboth on the river ruled in his place. And Saul died, and Baal-hanan ben Achbor ruled in his place. And Baal-hanan ben Achbor died, and Hadar ruled in his place, and the name of his city was Pau, and his wife's name was Mehetabel bat Matred bat Mezahab. And these are the names of the clans of Esau by their families, by their places, by their names: clan Timnah, clan Alvah, clan Jetheth, clan Aholibamah, clan Elah, clan Pinon, clan Kenaz, clan Teman, clan Mibzar, clan Magdiel, clan Iram.[32]

The Hebrew word translated as leader of a clan is aluf, used solely to describe the Dukes of Edom and Moab, in the first five books of Moses. However beginning in the books of the later prophets the word is used to describe Judean generals, for example, in the prophecies of Zachariah twice (9:7, 12:5–6) it had evolved to describe Jewish captains, the word also is used multiple times as a general term for teacher or guide for example in Psalm 55:13.[33] Aluph as it is used to denote teach or guide from the Edomite word for Duke is used 69 times in the Tanakh.

If the account may be taken at face value, the kingship of Edom was, at least in early times, not hereditary,[34] perhaps elective.[35] The first book of Chronicles mentions both a king and chieftains.[36] Moses and the Israelite people twice appealed to their common ancestry and asked the king of Edom for passage through his land, along the "King's Highway", on their way to Canaan, but the king refused permission.[37] Accordingly, they detoured around the country because of his show of force[38] or because God ordered them to do so rather than wage war (Deuteronomy 2:4–6). The King of Edom did not attack the Israelites, though he prepared to resist aggression.

Nothing further is recorded of the Edomites in the Tanakh until their defeat by King Saul of Israel in the late 11th century BC (1 Samuel 14:47). Forty years later King David and his general Joab defeated the Edomites in the "Valley of Salt" (probably near the Dead Sea; 2 Samuel 8:13–14; 1 Kings 9:15–16). An Edomite prince named Hadad escaped and fled to Egypt, and after David's death returned and tried to start a rebellion, but failed and went to Syria (Aramea).[39] From that time Edom remained a vassal of Israel. David placed over the Edomites Israelite governors or prefects,[40] and this form of government seems to have continued under Solomon. When Israel divided into two kingdoms Edom became a dependency of the Kingdom of Judah. In the time of Jehoshaphat (c. 870 – 849 BC) the Tanakh mentions a king of Edom,[41] who was probably an Israelite deputy appointed by the King of Judah. It also states that the inhabitants of Mount Seir invaded Judea in conjunction with Ammon and Moab, and that the invaders turned against one another and were all destroyed (2 Chronicles 20:10–23). Edom revolted against Jehoram and elected a king of its own (2 Kings 8:20–22; 2 Chronicles 21:8). Amaziah attacked and defeated the Edomites, seizing Selah, but the Israelites never subdued Edom completely (2 Kings 14:7; 2 Chronicles 25:11–12).

In the time of Nebuchadnezzar II the Edomites may have helped plunder Jerusalem and slaughter the Judaeans in 587 or 586 BCE (Psalms 137:7; Obadiah 1:11–14). For this reason the prophets denounced Edom (Isaiah 34:5–8; Jeremiah 49:7–22; Obadiah passim). Evidence also suggests that at this time Edom may have engaged in a treaty betrayal of Judah.[42]

Although the Idumaeans controlled the lands to the east and south of the Dead Sea, their peoples were held in contempt by the Israelites. Hence the Book of Psalms says "Moab is my washpot: over Edom will I cast out my shoe".[43] According to the Torah,[44] the congregation could not receive descendants of a marriage between an Israelite and an Edomite until the fourth generation. This law was a subject of controversy between Shimon ben Yohai, who said it applied only to male descendants, and other Tannaim, who said female descendants were also excluded[45] for four generations. From these, some early conversion laws in halacha were derived.

Classical Idumaea

During the revolt of the Maccabees against the Seleucid kingdom (early 2nd century BC), II Maccabees refers to a Seleucid general named Gorgias as "Governor of Idumaea"; whether he was a Greek or a Hellenized Edomite is unknown. Some scholars maintain that the reference to Idumaea in that passage is an error altogether. Judas Maccabeus conquered their territory for a time around 163 BC.[46] They were again subdued by John Hyrcanus (c. 125 BC), who forcibly converted them, among others, to Judaism,[47] and incorporated them into the Jewish nation.[35] Antipater the Idumaean, the progenitor of the Herodian Dynasty along with Judean progenitors, that ruled Judea after the Roman conquest, was of mixed Edomite/Judean origin. Under Herod the Great, the Idumaea province was ruled for him by a series of governors, among whom were his brother Joseph ben Antipater, and his brother-in-law Costobarus. Josephus, when referring to Upper Idumaea, speaks of towns and villages immediately to the south and south-west of Jerusalem, such as Hebron (Antiq. 12.8.6,Wars 4.9.7), Halhul, in Greek called Alurus (Wars 4.9.6), Bethsura (Antiq. 12.9.4), Marissa (Antiq. 13.9.1, Wars 1.2.5), Dura (Adorayim) (Antiq. 13.9.1, Wars 1.2.5), Caphethra (Wars 4.9.9), Bethletephon (Wars 4.8.1), and Tekoa (Wars 4.9.5). The Mishnah refers to Rabbi Ishmael's dwelling place in Kfar Aziz as being "near to Edom."[48] It is presumed that the Idumaean nation, by the 1st-century CE, had migrated northwards from places formerly held by them in the south during the time of Joshua.[49] By 66 CE, a civil war in Judea during the First Jewish–Roman War, when Simon bar Giora attacked the Jewish converts of Upper Idumea, brought near complete destruction to the surrounding villages and countryside in that region.[50]

The Gospel of Mark[51] includes Idumea, along with Judea, Jerusalem, Tyre, Sidon and lands east of the Jordan as the communities from which crowds came to Jesus by the Sea of Galilee.

According to Josephus, during the siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE by Titus, 20,000 Idumaeans, under the leadership of John, Simeon, Phinehas, and Jacob, helped the Zealots fight for independence from Rome, who were besieged in the Temple.[52] After the Jewish Wars, the Idumaean people are no longer mentioned in history, though the geographical region of "Idumea" is still referred to at the time of Jerome.[35]

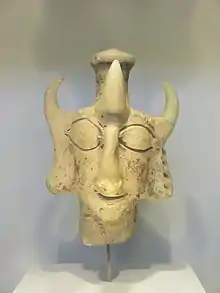

Religion

The nature of Edomite religion is largely unknown before their conversion to Judaism by the Hasmoneans. Epigraphical evidence suggests that the national god of Edom was Qaus (קוס) (also known as 'Qaush', 'Kaush', 'Kaus', 'Kos' or 'Qaws'), since Qaus is invoked in the blessing formula in letters and appear in personal names found in ancient Edom.[53] As close relatives of other Levantine Semites, they may have worshiped such gods as El, Baal, Qaus and Asherah. The oldest biblical traditions place Yahweh as the deity of southern Edom, and may have originated in "Edom/Seir/Teman/Sinai" before being adopted in Israel and Judah.[54] There is a Jewish tradition stemming from the Talmud, that the descendants of Esau would eventually become the Romans, and to a larger extent, all Europeans.[55][56]

Josephus states that Costobarus, appointed by Herod to be governor of Idumea and Gaza, was descended from the priests of "the Koze, whom the Idumeans had formerly served as a god".[57]

Victor Sasson describes an archaeological text that may well be Edomite, reflecting on the language, literature, and religion of Edom.[58]

Economy

The Kingdom of Edom drew much of its livelihood from the caravan trade between Egypt, the Levant, Mesopotamia, and southern Arabia, along the Incense Route. Astride the King's Highway, the Edomites were one of several states in the region for whom trade was vital due to the scarcity of arable land. It is also said that sea routes traded as far away as India, with ships leaving from the port of Ezion-Geber. Edom's location on the southern highlands left it with only a small strip of land that received sufficient rain for farming. Edom probably exported salt and balsam (used for perfume and temple incense in the ancient world) from the Dead Sea region.

Khirbat en-Nahas is a large-scale copper-mining site excavated by archaeologist Thomas Levy in what is now southern Jordan. The scale of tenth-century mining on the site is regarded as evidence of a strong, centralized 10th century BC Edomite kingdom.[59]

Notes

- "Edom". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- churchofjesuschrist.org: "Book of Mormon Pronunciation Guide" (retrieved 2012-02-25), IPA-ified from «ē´dum»

- Avraham Negev; Shimon Gibson (2001). Edom; Edomites. Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land. New York and London: Continuum. pp. 149–150. ISBN 0-8264-1316-1.

- Eph'al, Israel (1998). "Changes in Palestine during the Persian Period in Light of Epigraphic Sources". Israel Exploration Journal. 48 (1/2): 115.

- Prof. Itzhaq Beit-Arieh (December 1996). "Edomites Advance into Judah". Biblical Archaeology Review. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- Jan Gunneweg; Th. Beier; U. Diehl; D. Lambrecht; H. Mommsen (August 1991). "'Edomite', 'Negbite'and 'Midianite' pottery from the Negev desert and Jordan: instrumental neutron activation analysis results". Archaeometry. Oxford, UK: Oxford University. 33 (2): 239–253. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.1991.tb00701.x. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- Avraham Negev; Shimon Gibson (2001). Idumea. Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land. New York and London: Continuum. pp. 239–240. ISBN 0-8264-1316-1.

- Charles Léon Souvay, ed. (1910). "Idumea". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- "Edom". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- Genesis 25:25

- Genesis 25:29-34

- Genesis 36:9: This is the genealogy of Esau the father of the Edomites

- Gauthier, Henri (1925). Dictionnaire des Noms Géographiques Contenus dans les Textes Hiéroglyphiques Vol. 1. p. 126.

- Redford, Egypt, Canaan and Israel in Ancient Times, Princeton Univ. Press, 1992. p.228, 318.

- Smith, M.S. (2001). The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel's Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 145. ISBN 9780195134803. Retrieved 2015-09-10.

- Müller, Asien und Europa, p. 135.

- Ptolemy, "Geography," v. 16

- Strabo, Geography Bk.16.2.34

- "Herod | Biography & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-10-13.

- Retso, Jan (2013-07-04). The Arabs in Antiquity: Their History from the Assyrians to the Umayyads. Routledge. ISBN 9781136872891.

- Chancey, Mark A. (2002-05-23). The Myth of a Gentile Galilee. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139434652.

- Shahid, Irfan; Shahîd, Irfan (1984). Rome and the Arabs: A Prolegomenon to the Study of Byzantium and the Arabs. Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 9780884021155.

- "Israeli researchers identify biblical kingdom of Edom - Israel News - Jerusalem Post". www.jpost.com. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- Amanda Borschel-Dan. "Bible-era nomadic Edomite tribesmen were actually hi-tech copper mavens". www.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- Levy, Thomas E.; Najjar, Mohammad; Tirosh, Ofir; Yagel, Omri A.; Liss, Brady; Ben-Yosef, Erez (2019-09-18). "Ancient technology and punctuated change: Detecting the emergence of the Edomite Kingdom in the Southern Levant". PLOS ONE. 14 (9): e0221967. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1421967B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0221967. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6750566. PMID 31532811.

- Deuteronomy 1:2; Deuteronomy 2:1–8

- Judges 11:17–18; 2 Kings 3:8–9

- Deuteronomy 2:13–18

- Genesis 36:33; Isaiah 34:6, Isaiah 63:1, et al.

- 2 Kings 14:7

- 1 Kings 9:26

- Genesis 36:31–43

- אַלּוּף

- Gordon, Bruce R. "Edom (Idumaea)". Regnal Chronologies. Archived from the original on 2006-04-29. Retrieved 2006-08-04.

- Richard Gottheil, Max Seligsohn (1901-06-19). "Edom, Idumaea". The Jewish Encyclopedia. 3. Funk and Wagnalls. pp. 40–41. LCCN 16014703. Archived from the original on 2007-09-21. Retrieved 2005-07-25.

- 1 Chronicles 1:43–54

- Numbers 20:14–20, King James Version 1611

- Numbers 20:21

- 2 Samuel 9:14–22; Josephus, Jewish Antiquities viii. 7, S 6

- 2 Samuel 8:14

- 2 Kings 3:9–26

- Dykehouse, Jason (2013). "Biblical Evidence from Obadiah and Psalm 137 for an Edomite Treaty Betrayal of Judah in the Sixth Century B.C.E." Antiguo Oriente. 11: 75–122.

- Psalms 60:8 and Psalms 108:9

- Deuteronomy 23:8–9

- Yevamot 76b

- Josephus, "Ant." xii. 8, §§ 1, 6

- ib. xiii. 9, § 1; xiv. 4, § 4

- Mishna Kilaim 6:4; Ketuvot 5:8

- Joshua 15:21

- Josephus, De Bello Judaico (Wars of the Jews) IV, 514 (Wars of the Jews 4.9.3) and De Bello Judaico (Wars of the Jews) IV, 529 (Wars of the Jews 4.9.7)

- Mark 3:8

- Josephus, Jewish Wars iv. 4, § 5

- Ahituv, Shmuel. Echoes from the Past: Hebrew and Cognate Inscriptions from the Biblical Period. Jerusalem, Israel: Carta, 2008, pp. 351, 354

- M. Leuenberger (2017). "YHWH's Provenance from the South". In J. van Oorschot; M. Witte (eds.). The Origins of Yahwism. Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110447118.

- "Did the Edomite tribe Magdiel found Rome?".

- "Edomites".

in rabbinical sources, the word "Edom" was a code name for Rome

- Antiquities of the Jews, Book 15, chapter 7, section 9

- Victor Sasson (2006). "An Edomite Joban Text, with a Biblical Joban Parallel". Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft. doi:10.1515/zatw.2006.117.4.601.

- Kings of Controversy Robert Draper National Geographic, December 2010.

References

- Spencer, Richard (24 September 2019). "Scientists find state of Edom which they thought was a Bible story". The Times. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- Gottheil, Richard and M. Seligsohn. "Edom, Idumea." Jewish Encyclopedia. Funk and Wagnalls, 1901–1906; which cites:

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Edom". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Edom". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.