Ectopic pregnancy

Ectopic pregnancy is a complication of pregnancy in which the embryo attaches outside the uterus.[4] Signs and symptoms classically include abdominal pain and vaginal bleeding, but fewer than 50 percent of affected women have both of these symptoms.[1] The pain may be described as sharp, dull, or crampy.[1] Pain may also spread to the shoulder if bleeding into the abdomen has occurred.[1] Severe bleeding may result in a fast heart rate, fainting, or shock.[4][1] With very rare exceptions the fetus is unable to survive.[5]

| Ectopic pregnancy | |

|---|---|

| Other names | EP, eccyesis, extrauterine pregnancy, EUP, tubal pregnancy (when in fallopian tube) |

| |

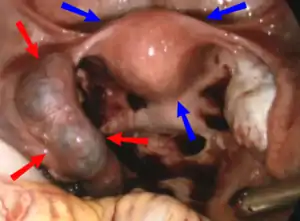

| Laparoscopic view, looking down at the uterus (marked by blue arrows). In the left Fallopian tube there is an ectopic pregnancy and bleeding (marked by red arrows). The right tube is normal. | |

| Specialty | Obstetrics and Gynaecology |

| Symptoms | Abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding[1] |

| Risk factors | Pelvic inflammatory disease, tobacco smoking, prior tubal surgery, history of infertility, use of assisted reproductive technology[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood tests for human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), ultrasound[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Miscarriage, ovarian torsion, acute appendicitis[1] |

| Treatment | Methotrexate, surgery[2] |

| Prognosis | Mortality 0.2% (developed world), 2% (developing world)[3] |

| Frequency | ~1.5% of pregnancies (developed world)[4] |

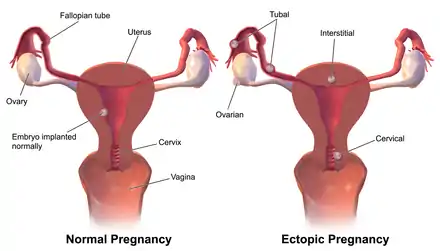

Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy include pelvic inflammatory disease, often due to chlamydia infection; tobacco smoking; prior tubal surgery; a history of infertility; and the use of assisted reproductive technology.[2] Those who have previously had an ectopic pregnancy are at much higher risk of having another one.[2] Most ectopic pregnancies (90%) occur in the fallopian tube, which are known as tubal pregnancies,[2] but implantation can also occur on the cervix, ovaries, cesarean scar, or within the abdomen.[1] Detection of ectopic pregnancy is typically by blood tests for human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and ultrasound.[1] This may require testing on more than one occasion.[1] Ultrasound works best when performed from within the vagina.[1] Other causes of similar symptoms include: miscarriage, ovarian torsion, and acute appendicitis.[1]

Prevention is by decreasing risk factors such as chlamydia infections through screening and treatment.[6] While some ectopic pregnancies will resolve without treatment, this approach has not been well studied as of 2014.[2] The use of the medication methotrexate works as well as surgery in some cases.[2] Specifically it works well when the beta-HCG is low and the size of the ectopic is small.[2] Surgery is still typically recommended if the tube has ruptured, there is a fetal heartbeat, or the person's vital signs are unstable.[2] The surgery may be laparoscopic or through a larger incision, known as a laparotomy.[4] Maternal morbidity and mortality are reduced with treatment.[2]

The rate of ectopic pregnancy is about 1% and 2% that of live births in developed countries, though it may be as high as 4% among those using assisted reproductive technology.[4] It is the most common cause of death among women during the first trimester at approximately 10% of the total.[2] In the developed world outcomes have improved while in the developing world they often remain poor.[6] The risk of death among those in the developed world is between 0.1 and 0.3 percent while in the developing world it is between one and three percent.[3] The first known description of an ectopic pregnancy is by Al-Zahrawi in the 11th century.[6] The word "ectopic" means "out of place".[7]

Signs and symptoms

Up to 10% of women with ectopic pregnancy have no symptoms, and one third have no medical signs.[4] In many cases the symptoms have low specificity, and can be similar to those of other genitourinary and gastrointestinal disorders, such as appendicitis, salpingitis, rupture of a corpus luteum cyst, miscarriage, ovarian torsion or urinary tract infection.[4] Clinical presentation of ectopic pregnancy occurs at a mean of 7.2 weeks after the last normal menstrual period, with a range of four to eight weeks. Later presentations are more common in communities deprived of modern diagnostic ability.

Signs and symptoms of ectopic pregnancy include increased hCG, vaginal bleeding (in varying amounts), sudden lower abdominal pain,[4] pelvic pain, a tender cervix, an adnexal mass, or adnexal tenderness.[1] In the absence of ultrasound or hCG assessment, heavy vaginal bleeding may lead to a misdiagnosis of miscarriage.[4] Nausea, vomiting and diarrhea are more rare symptoms of ectopic pregnancy.[4]

Rupture of an ectopic pregnancy can lead to symptoms such as abdominal distension, tenderness, peritonism and hypovolemic shock.[4] A woman with ectopic pregnancy may be excessively mobile with upright posturing, in order to decrease intrapelvic blood flow, which can lead to swelling of the abdominal cavity and cause additional pain.[8]

Complications

The most common complication is rupture with internal bleeding which may lead to hypovolemic shock. Death from rupture is the leading cause of death in the first trimester of the pregnancy.[9][10][11]

Causes

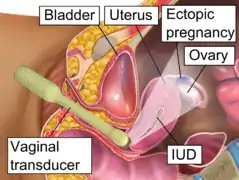

There are a number of risk factors for ectopic pregnancies. However, in as many as one third[12] to one half[13] no risk factors can be identified. Risk factors include: pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, use of an intrauterine device (IUD), previous exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES), tubal surgery, intrauterine surgery (e.g. D&C), smoking, previous ectopic pregnancy, endometriosis, and tubal ligation.[14][15] A previous induced abortion does not appear to increase the risk.[16] The intrauterine device (IUD) does not increase the risk of ectopic pregnancy, but with an IUD if pregnancy occurs it is more likely to be ectopic than intrauterine.[17] The risk of ectopic pregnancy after chlamydia infection is low.[18] The exact mechanism through which chlamydia increases the risk of ectopic pregnancy is uncertain, though some research suggests that the infection can affect the structure of Fallopian tubes.[19]

| Relative risk factors | |

|---|---|

| High | Tubal sterilization, IUD, prior ectopic, PID (pelvic inflammatory disease), SIN (salpingitis isthmica nodosa) |

| Moderate | Smoking, having more than 1 partner, infertility, chlamydia |

| Low | Douching, age greater than 35, age less than 18, GIFT (gamete intrafallopian transfer) |

Tube damage

Tubal pregnancy is when the egg is implanted in the fallopian tubes. Hair-like cilia located on the internal surface of the fallopian tubes carry the fertilized egg to the uterus. Fallopian cilia are sometimes seen in reduced numbers subsequent to an ectopic pregnancy, leading to a hypothesis that cilia damage in the fallopian tubes is likely to lead to an ectopic pregnancy.[21] Women who smoke have a higher chance of an ectopic pregnancy in the fallopian tubes. Smoking leads to risk factors of damaging and killing cilia.[21] As cilia degenerate, the amount of time it takes for the fertilized egg to reach the uterus will increase. The fertilized egg, if it doesn't reach the uterus in time, will hatch from the non-adhesive zona pellucida and implant itself inside the fallopian tube, thus causing the ectopic pregnancy.

Women with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) have a high occurrence of ectopic pregnancy.[22] This results from the build-up of scar tissue in the fallopian tubes, causing damage to cilia.[23] If however both tubes were completely blocked, so that sperm and egg were physically unable to meet, then fertilization of the egg would naturally be impossible, and neither normal pregnancy nor ectopic pregnancy could occur. Intrauterine adhesions (IUA) present in Asherman's syndrome can cause ectopic cervical pregnancy or, if adhesions partially block access to the tubes via the ostia, ectopic tubal pregnancy.[24][25][26] Asherman's syndrome usually occurs from intrauterine surgery, most commonly after D&C.[24] Endometrial/pelvic/genital tuberculosis, another cause of Asherman's syndrome, can also lead to ectopic pregnancy as infection may lead to tubal adhesions in addition to intrauterine adhesions.[27]

Tubal ligation can predispose to ectopic pregnancy. Reversal of tubal sterilization (tubal reversal) carries a risk for ectopic pregnancy. This is higher if more destructive methods of tubal ligation (tubal cautery, partial removal of the tubes) have been used than less destructive methods (tubal clipping). A history of a tubal pregnancy increases the risk of future occurrences to about 10%.[23] This risk is not reduced by removing the affected tube, even if the other tube appears normal. The best method for diagnosing this is to do an early ultrasound.

Other

Although some investigations have shown that patients may be at higher risk for ectopic pregnancy with advancing age, it is believed that age is a variable which could act as a surrogate for other risk factors. Vaginal douching is thought by some to increase ectopic pregnancies.[23] Women exposed to DES in utero (also known as "DES daughters") also have an elevated risk of ectopic pregnancy.[28] However, DES has not been used since 1971 in the United States.[28] It has also been suggested that pathologic generation of nitric oxide through increased iNOS production may decrease tubal ciliary beats and smooth muscle contractions and thus affect embryo transport, which may consequently result in ectopic pregnancy.[29] The low socioeconomic status may be risk factors for ectopic pregnancy.[30]

Diagnosis

An ectopic pregnancy should be considered as the cause of abdominal pain or vaginal bleeding in every woman who has a positive pregnancy test.[1] The primary goal of diagnostic procedures in possible ectopic pregnancy is to triage according to risk rather than establishing pregnancy location.[4]

Transvaginal ultrasonography

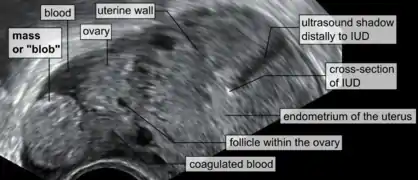

An ultrasound showing a gestational sac with fetal heart in the fallopian tube has a very high specificity of ectopic pregnancy. Transvaginal ultrasonography has a sensitivity of at least 90% for ectopic pregnancy.[4] The diagnostic ultrasonographic finding in ectopic pregnancy is an adnexal mass that moves separately from the ovary. In around 60% of cases, it is an inhomogeneous or a noncystic adnexal mass sometimes known as the "blob sign". It is generally spherical, but a more tubular appearance may be seen in case of hematosalpinx. This sign has been estimated to have a sensitivity of 84% and specificity of 99% in diagnosing ectopic pregnancy.[4] In the study estimating these values, the blob sign had a positive predictive value of 96% and a negative predictive value of 95%.[4] The visualization of an empty extrauterine gestational sac is sometimes known as the "bagel sign", and is present in around 20% of cases.[4] In another 20% of cases, there is visualization of a gestational sac containing a yolk sac or an embryo.[4] Ectopic pregnancies where there is visualization of cardiac activity are sometimes termed "viable ectopic".[4]

Transvaginal ultrasonography of an ectopic pregnancy, showing the field of view in the following image.

Transvaginal ultrasonography of an ectopic pregnancy, showing the field of view in the following image. A "blob sign", which consists of the ectopic pregnancy. The ovary is distinguished from it by having follicles, whereof one is visible in the field. This patient had an intrauterine device (IUD) with progestogen, whose cross-section is visible in the field, leaving an ultrasound shadow distally to it.

A "blob sign", which consists of the ectopic pregnancy. The ovary is distinguished from it by having follicles, whereof one is visible in the field. This patient had an intrauterine device (IUD) with progestogen, whose cross-section is visible in the field, leaving an ultrasound shadow distally to it. Ultrasound image showing an ectopic pregnancy where a gestational sac and fetus has been formed.

Ultrasound image showing an ectopic pregnancy where a gestational sac and fetus has been formed.

The combination of a positive pregnancy test and the presence of what appears to be a normal intrauterine pregnancy does not exclude an ectopic pregnancy, since there may be either a heterotopic pregnancy or a "pseudosac", which is a collection of within the endometrial cavity that may be seen in up to 20% of women.[4]

A small amount of anechogenic-free fluid in the recto-uterine pouch is commonly found in both intrauterine and ectopic pregnancies.[4] The presence of echogenic fluid is estimated at between 28 and 56% of women with an ectopic pregnancy, and strongly indicates the presence of hemoperitoneum.[4] However, it does not necessarily result from tubal rupture but is commonly a result from leakage from the distal tubal opening.[4] As a rule of thumb, the finding of free fluid is significant if it reaches the fundus or is present in the vesico-uterine pouch.[4] A further marker of serious intra-abdominal bleeding is the presence of fluid in the hepatorenal recess of the subhepatic space.[4]

Currently, Doppler ultrasonography is not considered to significantly contribute to the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy.[4]

A common misdiagnosis is of a normal intrauterine pregnancy is where the pregnancy is implanted laterally in an arcuate uterus, potentially being misdiagnosed as an interstitial pregnancy.[4]

Ultrasonography and β-hCG

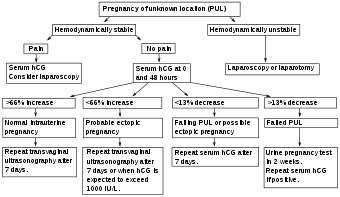

Where no intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) is seen on ultrasound, measuring β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) levels may aid in the diagnosis. The rationale is that a low β-hCG level may indicate that the pregnancy is intrauterine but yet too small to be visible on ultrasonography. While some physicians consider that the threshold where an intrauterine pregnancy should be visible on transvaginal ultrasound is around 1500 mIU/ml of β-hCG, a review in the JAMA Rational Clinical Examination Series showed that there is no single threshold for the β-human chorionic gonadotropin that confirms an ectopic pregnancy. Instead, the best test in a pregnant woman is a high resolution transvaginal ultrasound.[1] The presence of an adnexal mass in the absence of an intrauterine pregnancy on transvaginal sonography increases the likelihood of an ectopic pregnancy 100-fold (LR+ 111). When there are no adnexal abnormalities on transvaginal sonography, the likelihood of an ectopic pregnancy decreases (LR- 0.12). An empty uterus with levels higher than 1500 mIU/ml may be evidence of an ectopic pregnancy, but may also be consistent with an intrauterine pregnancy which is simply too small to be seen on ultrasound. If the diagnosis is uncertain, it may be necessary to wait a few days and repeat the blood work. This can be done by measuring the β-hCG level approximately 48 hours later and repeating the ultrasound. The serum hCG ratios and logistic regression models appear to be better than absolute single serum hCG level.[32] If the β-hCG falls on repeat examination, this strongly suggests a spontaneous abortion or rupture. The fall in serum hCG over 48 hours may be measured as the hCG ratio, which is calculated as:[4]

An hCG ratio of 0.87, that is, a decrease in hCG of 13% over 48 hours, has a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 97% for predicting a failing pregnancy of unknown location (PUL).[4] The majority of cases of ectopic pregnancy will have serial serum hCG levels that increase more slowly than would be expected with an IUP (that is, a suboptimal rise), or decrease more slowly than would be expected with a failing PUL. However, up to 20% of cases of ectopic pregnancy have serum hCG doubling times similar to that of an IUP, and around 10% of EP cases have hCG patterns similar to a failing PUL.[4]

Direct examination

A laparoscopy or laparotomy can also be performed to visually confirm an ectopic pregnancy. This is generally reserved for women presenting with signs of an acute abdomen and hypovolemic shock.[4] Often if a tubal abortion or tubal rupture has occurred, it is difficult to find the pregnancy tissue. A laparoscopy in very early ectopic pregnancy rarely shows a normal-looking fallopian tube.

Culdocentesis

Culdocentesis, in which fluid is retrieved from the space separating the vagina and rectum, is a less commonly performed test that may be used to look for internal bleeding. In this test, a needle is inserted into the space at the very top of the vagina, behind the uterus and in front of the rectum. Any blood or fluid found may have been derived from a ruptured ectopic pregnancy.

Progesterone levels

Progesterone levels of less than 20 nmol/l have a high predictive value for failing pregnancies, whilst levels over 25 nmol/l are likely to predict viable pregnancies, and levels over 60 nmol/l are strongly so. This may help in identifying failing PUL that are at low risk and thereby needing less follow-up.[4] Inhibin A may also be useful for predicting spontaneous resolution of PUL, but is not as good as progesterone for this purpose.[4]

Mathematical models

There are various mathematical models, such as logistic regression models and Bayesian networks, for the prediction of PUL outcome based on multiple parameters.[4] Mathematical models also aim to identify PULs that are low risk, that is, failing PULs and IUPs.[4]

Dilation and curettage

Dilation and curettage (D&C) is sometimes used to diagnose pregnancy location with the aim of differentiating between an EP and a non-viable IUP in situations where a viable IUP can be ruled out. Specific indications for this procedure include either of the following:[4]

- No visible IUP on transvaginal ultrasonography with a serum hCG of more than 2000 mIU/ml.

- An abnormal rise in hCG level. A rise of 35% over 48 hours is proposed as the minimal rise consistent with a viable intrauterine pregnancy.

- An abnormal fall in hCG level, such as defined as one of less than 20% in two days.

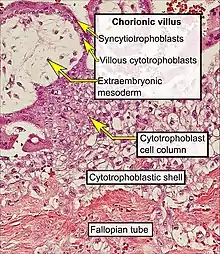

Tubal pregnancy

The vast majority of ectopic pregnancies implant in the Fallopian tube. Pregnancies can grow in the fimbrial end (5% of all ectopic pregnancies), the ampullary section (80%), the isthmus (12%), and the cornual and interstitial part of the tube (2%).[23] Mortality of a tubal pregnancy at the isthmus or within the uterus (interstitial pregnancy) is higher as there is increased vascularity that may result more likely in sudden major internal bleeding. A review published in 2010 supports the hypothesis that tubal ectopic pregnancy is caused by a combination of retention of the embryo within the fallopian tube due to impaired embryo-tubal transport and alterations in the tubal environment allowing early implantation to occur.[33]

Nontubal ectopic pregnancy

Two percent of ectopic pregnancies occur in the ovary, cervix, or are intra-abdominal. Transvaginal ultrasound examination is usually able to detect a cervical pregnancy. An ovarian pregnancy is differentiated from a tubal pregnancy by the Spiegelberg criteria.[34]

While a fetus of ectopic pregnancy is typically not viable, very rarely, a live baby has been delivered from an abdominal pregnancy. In such a situation the placenta sits on the intra-abdominal organs or the peritoneum and has found sufficient blood supply. This is generally bowel or mesentery, but other sites, such as the renal (kidney), liver or hepatic (liver) artery or even aorta have been described. Support to near viability has occasionally been described, but even in Third World countries, the diagnosis is most commonly made at 16 to 20 weeks' gestation. Such a fetus would have to be delivered by laparotomy. Maternal morbidity and mortality from extrauterine pregnancy are high as attempts to remove the placenta from the organs to which it is attached usually lead to uncontrollable bleeding from the attachment site. If the organ to which the placenta is attached is removable, such as a section of bowel, then the placenta should be removed together with that organ. This is such a rare occurrence that true data is unavailable and reliance must be made on anecdotal reports.[35][36][37] However, the vast majority of abdominal pregnancies require intervention well before fetal viability because of the risk of bleeding.

With the increase in Cesarean sections performed worldwide,[38][39] cesarean section ectopic pregnancies (CSP) are rare, but becoming more common. The incidence of CSP is not well known, however there have been estimates based on different populations of 1:1800-1:2216.[40][41] CSP are characterized by abnormal implantation into the scar from a previous cesarean section,[42] and allowed to continue can cause serious complications such as uterine rupture and hemorrhage.[41] Patients with CSP generally present without symptoms, however symptoms can include vaginal bleeding that may or may not be associated with pain.[43][44] The diagnosis of CSP is made by ultrasound and four characteristics are noted: (1) Empty uterine cavity with bright hyperechoic endometrial stripe (2) Empty cervical canal (3) Intrauterine mass in the anterior part of the uterine isthmus, and (4) Absence of the anterior uterine muscle layer, and/or absence or thinning between the bladder and gestational sac, measuring less than 5 mm.[42][45][46] Given the rarity of the diagnosis, treatment options tend to be described in case reports and series, ranging from medical with methotrexate or KCl[47] to surgical with dilation and curettage,[48] uterine wedge resection, or hysterectomy.[44] A double-balloon catheter technique has also been described,[49] allowing for uterine preservation. Recurrence risk for CSP is unknown, and early ultrasound in the next pregnancy is recommended.[42]

Heterotopic pregnancy

In rare cases of ectopic pregnancy, there may be two fertilized eggs, one outside the uterus and the other inside. This is called a heterotopic pregnancy.[1] Often the intrauterine pregnancy is discovered later than the ectopic, mainly because of the painful emergency nature of ectopic pregnancies. Since ectopic pregnancies are normally discovered and removed very early in the pregnancy, an ultrasound may not find the additional pregnancy inside the uterus. When hCG levels continue to rise after the removal of the ectopic pregnancy, there is the chance that a pregnancy inside the uterus is still viable. This is normally discovered through an ultrasound.

Although rare, heterotopic pregnancies are becoming more common, likely due to increased use of IVF. The survival rate of the uterine fetus of a heterotopic pregnancy is around 70%.[50]

Persistent ectopic pregnancy

A persistent ectopic pregnancy refers to the continuation of trophoblastic growth after a surgical intervention to remove an ectopic pregnancy. After a conservative procedure that attempts to preserve the affected fallopian tube such as a salpingotomy, in about 15–20% the major portion of the ectopic growth may have been removed, but some trophoblastic tissue, perhaps deeply embedded, has escaped removal and continues to grow, generating a new rise in hCG levels.[51] After weeks this may lead to new clinical symptoms including bleeding. For this reason hCG levels may have to be monitored after removal of an ectopic pregnancy to assure their decline, also methotrexate can be given at the time of surgery prophylactically.

Pregnancy of unknown location

Pregnancy of unknown location (PUL) is the term used for a pregnancy where there is a positive pregnancy test but no pregnancy has been visualized using transvaginal ultrasonography.[4] Specialized early pregnancy departments have estimated that between 8% and 10% of women attending for an ultrasound assessment in early pregnancy will be classified as having a PUL.[4] The true nature of the pregnancy can be an ongoing viable intrauterine pregnancy, a failed pregnancy, an ectopic pregnancy or rarely a persisting PUL.[4]

Because of frequent ambiguity on ultrasonography examinations, the following classification is proposed:[4]

| Condition | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Definite ectopic pregnancy | Extrauterine gestational sac with yolk sac or embryo (with or without cardiac activity). |

| Pregnancy of unknown location – probable ectopic pregnancy | Inhomogeneous adnexal mass or extrauterine sac-like structure. |

| "True" pregnancy of unknown location | No signs of intrauterine nor extrauterine pregnancy on transvaginal ultrasonography. |

| Pregnancy of unknown location – probable intrauterine pregnancy | Intrauterine gestational sac-like structure. |

| Definite intrauterine pregnancy | Intrauterine gestational sac with yolk sac or embryo (with or without cardiac activity). |

In women with a pregnancy of unknown location, between 6% and 20% have an ectopic pregnancy.[4] In cases of pregnancy of unknown location and a history of heavy bleeding, it has been estimated that approximately 6% have an underlying ectopic pregnancy.[4] Between 30% and 47% of women with pregnancy of unknown location are ultimately diagnosed with an ongoing intrauterine pregnancy, whereof the majority (50–70%) will be found to have failing pregnancies where the location is never confirmed.[4]

Persisting PUL is where the hCG level does not spontaneously decline and no intrauterine or ectopic pregnancy is identified on follow-up transvaginal ultrasonography.[4] A persisting PUL is likely either a small ectopic pregnancy that has not been visualized, or a retained trophoblast in the endometrial cavity.[4] Treatment should only be considered when a potentially viable intrauterine pregnancy has been definitively excluded.[4] A treated persistent PUL is defined as one managed medically (generally with methotrexate) without confirmation of the location of the pregnancy such as by ultrasound, laparoscopy or uterine evacuation.[4] A resolved persistent PUL is defined as serum hCG reaching a non-pregnant value (generally less than 5 IU/l) after expectant management, or after uterine evacuation without evidence of chorionic villi on histopathological examination.[4] In contrast, a relatively low and unresolving level of serum hCG indicates the possibility of an hCG-secreting tumour.[4]

Differential diagnosis

Other conditions that cause similar symptoms include: miscarriage, ovarian torsion, and acute appendicitis, ruptured ovarian cyst, kidney stone, and pelvic inflammatory disease, among others.[1]

Treatment

Expectant management

Most women with a PUL are followed up with serum hCG measurements and repeat TVS examinations until a final diagnosis is confirmed.[4] Low-risk cases of PUL that appear to be failing pregnancies may be followed up with a urinary pregnancy test after two weeks and get subsequent telephone advice.[4] Low-risk cases of PUL that are likely intrauterine pregnancies may have another TVS in two weeks to access viability.[4] High-risk cases of PUL require further assessment, either with a TVS within 48 h or additional hCG measurement.[4]

Medical

Early treatment of an ectopic pregnancy with methotrexate is a viable alternative to surgical treatment[52] which was developed in the 1980s.[53] If administered early in the pregnancy, methotrexate terminates the growth of the developing embryo; this may cause an abortion, or the developing embryo may then be either resorbed by the woman's body or pass with a menstrual period. Contraindications include liver, kidney, or blood disease, as well as an ectopic embryonic mass > 3.5 cm.

Also, it may lead to the inadvertent termination of an undetected intrauterine pregnancy, or severe abnormality in any surviving pregnancy.[4] Therefore, it is recommended that methotrexate should only be administered when hCG has been serially monitored with a rise less than 35% over 48 hours, which practically excludes a viable intrauterine pregnancy.[4]

For nontubal ectopic pregnancy, evidence from randomised clinical trials in women with CSP is uncertain regarding treatment success, complications and side effects of methotrexate compared with surgery (uterine arterial embolization or uterine arterial chemoembolization).[54]

The United States uses a multi dose protocol of methotrexate (MTX) which involves 4 doses of intramuscular along with an intramuscular injection of folinic acid to protect cells from the effects of the drugs and to reduce side effects. In France, the single dose protocol is followed, but a single dose has a greater chance of failure.[55]

Surgery

If bleeding has already occurred, surgical intervention may be necessary. However, whether to pursue surgical intervention is an often difficult decision in a stable patient with minimal evidence of blood clot on ultrasound.

Surgeons use laparoscopy or laparotomy to gain access to the pelvis and can either incise the affected Fallopian and remove only the pregnancy (salpingostomy) or remove the affected tube with the pregnancy (salpingectomy). The first successful surgery for an ectopic pregnancy was performed by Robert Lawson Tait in 1883.[56] It is estimated that an acceptable rate of PULs that eventually undergo surgery is between 0.5 and 11%.[4] People that undergo salpingectomy and salpingostomy have a similar recurrent ectopic pregnancy rate of 5% and 8% respectively. Additionally, their intrauterine pregnancy rates are also similar, 56% and 61%.[57]

Autotransfusion of a woman's own blood as drained during surgery may be useful in those who have a lot of bleeding into their abdomen.[58]

Published reports that a re-implanted embryo survived to birth were debunked as false.[59]

Prognosis

When ectopic pregnancies are treated, the prognosis for the mother is very good in Western countries; maternal death is rare, but most fetuses die or are aborted. For instance, in the UK, between 2003 and 2005 there were 32,100 ectopic pregnancies resulting in 10 maternal deaths (meaning that 1 in 3,210 women with an ectopic pregnancy died).[60] In 2006–2008 the UK Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths found that ectopic pregnancy is the cause of 6 maternal deaths (.26/100,000 pregnancies).[17]

In the developing world, however, especially in Africa, the death rate is very high, and ectopic pregnancies are a major cause of death among women of childbearing age.

In women having had an ectopic pregnancy, the risk of another one in the next pregnancy is around 10%.[61]

Future fertility

Fertility following ectopic pregnancy depends upon several factors, the most important of which is a prior history of infertility.[62] The treatment choice does not play a major role; A randomized study in 2013 concluded that the rates of intrauterine pregnancy two years after treatment of ectopic pregnancy are approximately 64% with radical surgery, 67% with medication, and 70% with conservative surgery.[63] In comparison, the cumulative pregnancy rate of women under 40 years of age in the general population over two years is over 90%.[64]

Methotrexate does not affect future fertility treatments. The number of oocytes that were retrieved before and after treatment with methotrexate does not change.[65]

In case of ovarian ectopic pregnancy, the risk of subsequent ectopic pregnancy or infertility is low.[66]

There is no evidence that massage improves fertility after ectopic pregnancy.[67]

Epidemiology

The rate of ectopic pregnancy is about 1% and 2% of that of live births in developed countries, though it is as high as 4% in pregnancies involving assisted reproductive technology.[4] Between 93% and 97% of ectopic pregnancies are located in a fallopian tube.[1] Of these, in turn, 13% are located in the isthmus, 75% are located in the ampulla, and 12% in the fimbriae.[4] Ectopic pregnancy is responsible for 6% of maternal deaths during the first trimester of pregnancy making it the leading cause of maternal death during this stage of pregnancy.[1]

Between 5% and 42% of women seen for ultrasound assessment with a positive pregnancy test have a pregnancy of unknown location, that is a positive pregnancy test but no pregnancy visualized at transvaginal ultrasonography.[4] Between 6% and 20% of pregnancy of unknown location are subsequently diagnosed with actual ectopic pregnancy.[4]

Society and culture

Salpingectomy as a treatment for ectopic pregnancy is one of the common cases when the principle of double effect can be used to justify accelerating the death of the embryo by doctors and patients opposed to outright abortions.[69]

In the Catholic Church, there are moral debates on certain treatments. A significant number of Catholic moralists consider use of methotrexate and the salpingostomy procedure to be not "morally permissible" because they destroy the embryo; however, situations are considered differently in which the mother's health is endangered, and the whole fallopian tube with the developing embryo inside is removed.[70][71]

Live birth

There have been cases where ectopic pregnancy lasted many months and ended in a live baby delivered by laparotomy.

In July 1999, Lori Dalton gave birth by caesarean section in Ogden, Utah, United States, to a healthy baby girl, Saige, who had developed outside of the uterus. Previous ultrasounds had not discovered the problem. "[Dalton]'s delivery was slated as a routine Caesarean birth at Ogden Regional Medical Center in Utah. When Dr. Naisbitt performed Lori's Caesarean, he was astonished to find Sage within the amniotic membrane outside the womb ... ."[72] "But what makes this case so rare is that not only did mother and baby survive—they're both in perfect health. The father, John Dalton took home video inside the delivery room. Saige came out doing extremely well because even though she had been implanted outside the womb, a rich blood supply from a uterine fibroid along the outer uterus wall had nourished her with a rich source of blood."[73]

In September 1999 an English woman, Jane Ingram (age 32) gave birth to triplets: Olivia, Mary and Ronan, with an extrauterine fetus (Ronan) below the womb and twins in the womb. All three survived. The twins in the womb were taken out first.[74]

On May 29, 2008 an Australian woman, Meera Thangarajah (age 34), who had an ectopic pregnancy in the ovary, gave birth to a healthy full term 6 pound 3 ounce (2.8 kg) baby girl, Durga, via caesarean section. She had no problems or complications during the 38‑week pregnancy.[75][76]

Other animals

Ectopic gestation exists in mammals other than humans. In sheep, it can go to term, with mammary preparation to parturition, and expulsion efforts. The fetus can be removed by caesarean section. Pictures of caesarian section of a euthanized ewe, five days after parturition signs.

Leg of fetal lamb appearing out of the uterus during caesarian section.

Leg of fetal lamb appearing out of the uterus during caesarian section. External view of fetal sac, necrotic distal part.

External view of fetal sac, necrotic distal part. Internal view of fetal sac, before resection of distal necrotic part.

Internal view of fetal sac, before resection of distal necrotic part. Internal view of fetal sac, the necrotic distal part is to the left.

Internal view of fetal sac, the necrotic distal part is to the left. External side of fetal sac, proximal end, with ovary and uterine horn.

External side of fetal sac, proximal end, with ovary and uterine horn. Resected distal part of fetal sac, with attached placenta.

Resected distal part of fetal sac, with attached placenta.

References

- Crochet JR, Bastian LA, Chireau MV (April 2013). "Does this woman have an ectopic pregnancy?: the rational clinical examination systematic review". JAMA. 309 (16): 1722–9. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.3914. PMID 23613077. S2CID 205049738.

- Cecchino GN, Araujo Júnior E, Elito Júnior J (September 2014). "Methotrexate for ectopic pregnancy: when and how". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 290 (3): 417–23. doi:10.1007/s00404-014-3266-9. PMID 24791968. S2CID 26727563.

- Mignini L (26 September 2007). "Interventions for tubal ectopic pregnancy". who.int. The WHO Reproductive Health Library. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- Kirk E, Bottomley C, Bourne T (2014). "Diagnosing ectopic pregnancy and current concepts in the management of pregnancy of unknown location". Human Reproduction Update. 20 (2): 250–61. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt047. PMID 24101604.

- Zhang J, Li F, Sheng Q (2008). "Full-term abdominal pregnancy: a case report and review of the literature". Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation. 65 (2): 139–41. doi:10.1159/000110015. PMID 17957101. S2CID 35923100.

- Nama V, Manyonda I (April 2009). "Tubal ectopic pregnancy: diagnosis and management". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 279 (4): 443–53. doi:10.1007/s00404-008-0731-3. PMID 18665380. S2CID 22538462.

- Cornog MW (1998). Merriam-Webster's vocabulary uilder. Springfield, Mass.: Merriam-Webster. p. 313. ISBN 9780877799108. Archived from the original on 2017-09-10.

- Skipworth RJ (December 2011). "A new clinical sign in ruptured ectopic pregnancy". Lancet. 378 (9809): e27. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(11)61901-6. PMID 22177516. S2CID 333306.

- "Ectopic pregnancy". Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- Pediatric clinical advisor : instant diagnosis and treatment (2 ed.). Mosby Elsevier. 2007. pp. 180–181. ISBN 978-0-323-03506-4.

- Tenore JL (February 2000). "Ectopic pregnancy". American Family Physician. 61 (4): 1080–8. PMID 10706160.

- Farquhar CM (2005). "Ectopic pregnancy". Lancet. 366 (9485): 583–91. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67103-6. PMID 16099295. S2CID 26445888.

- Majhi AK, Roy N, Karmakar KS, Banerjee PK (June 2007). "Ectopic pregnancy--an analysis of 180 cases". Journal of the Indian Medical Association. 105 (6): 308, 310, 312 passim. PMID 18232175.

- "BestBets: Risk Factors for Ectopic Pregnancy". Archived from the original on 2008-12-19.

- Rana P, Kazmi I, Singh R, Afzal M, Al-Abbasi FA, Aseeri A, et al. (October 2013). "Ectopic pregnancy: a review". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 288 (4): 747–57. doi:10.1007/s00404-013-2929-2. PMID 23793551. S2CID 42807796.

- "16 Answering questions about long term outcomes". Management of Unintended and Abnormal Pregnancy: Comprehensive Abortion Care. John Wiley & Sons. 2011. ISBN 9781444358476. Archived from the original on 2017-09-10.

- Kumar V, Gupta J (November 2015). "Tubal ectopic pregnancy". BMJ Clinical Evidence. 2015. PMC 4646159. PMID 26571203.

- Bakken IJ (February 2008). "Chlamydia trachomatis and ectopic pregnancy: recent epidemiological findings". Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 21 (1): 77–82. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e3282f3d972. PMID 18192790. S2CID 30584041.

- Sivalingam VN, Duncan WC, Kirk E, Shephard LA, Horne AW (October 2011). "Diagnosis and management of ectopic pregnancy". The Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care. 37 (4): 231–40. doi:10.1136/jfprhc-2011-0073. PMC 3213855. PMID 21727242.

- Marion LL, Meeks GR (June 2012). "Ectopic pregnancy: History, incidence, epidemiology, and risk factors". Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 55 (2): 376–86. doi:10.1097/GRF.0b013e3182516d7b. PMID 22510618.

- Lyons RA, Saridogan E, Djahanbakhch O (2006). "The reproductive significance of human Fallopian tube cilia". Human Reproduction Update. 12 (4): 363–72. doi:10.1093/humupd/dml012. PMID 16565155.

- Tay JI, Moore J, Walker JJ (August 2000). "Ectopic pregnancy". The Western Journal of Medicine. 173 (2): 131–4. doi:10.1136/ewjm.173.2.131. PMC 1071024. PMID 10924442.

- Speroff L, Glass RH, Kase NG (1999). Clinical Gynecological Endocrinology and Infertility, 6th Ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (1999). p. 1149ff. ISBN 978-0-683-30379-7.

- Schenker JG, Margalioth EJ (May 1982). "Intrauterine adhesions: an updated appraisal". Fertility and Sterility. 37 (5): 593–610. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(16)46268-0. PMID 6281085.

- Kłyszejko C, Bogucki J, Kłyszejko D, Ilnicki W, Donotek S, Koźma J (January 1987). "[Cervical pregnancy in Asherman's syndrome]". Ginekologia Polska. 58 (1): 46–8. PMID 3583040.

- Dicker D, Feldberg D, Samuel N, Goldman JA (January 1985). "Etiology of cervical pregnancy. Association with abortion, pelvic pathology, IUDs and Asherman's syndrome". The Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 30 (1): 25–7. PMID 4038744.

- Bukulmez O, Yarali H, Gurgan T (August 1999). "Total corporal synechiae due to tuberculosis carry a very poor prognosis following hysteroscopic synechialysis". Human Reproduction. 14 (8): 1960–1. doi:10.1093/humrep/14.8.1960. PMID 10438408.

- Schrager S, Potter BE (May 2004). "Diethylstilbestrol exposure". American Family Physician. 69 (10): 2395–400. PMID 15168959. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02.

- Al-Azemi M, Refaat B, Amer S, Ola B, Chapman N, Ledger W (August 2010). "The expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in the human fallopian tube during the menstrual cycle and in ectopic pregnancy". Fertility and Sterility. 94 (3): 833–40. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.04.020. PMID 19482272.

- Yuk JS, Kim YJ, Hur JY, Shin JH (August 2013). "Association between socioeconomic status and ectopic pregnancy rate in the Republic of Korea". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 122 (2): 104–7. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.03.015. PMID 23726169. S2CID 25547683.

- "UOTW #61 - Ultrasound of the Week". Ultrasound of the Week. 14 October 2015. Archived from the original on 9 May 2017.

- van Mello NM, Mol F, Opmeer BC, Ankum WM, Barnhart K, Coomarasamy A, et al. (2012). "Diagnostic value of serum hCG on the outcome of pregnancy of unknown location: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Human Reproduction Update. 18 (6): 603–17. doi:10.1093/humupd/dms035. PMID 22956411.

- Shaw JL, Dey SK, Critchley HO, Horne AW (January 2010). "Current knowledge of the aetiology of human tubal ectopic pregnancy". Human Reproduction Update. 16 (4): 432–44. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmp057. PMC 2880914. PMID 20071358.

- Spiegelberg's criteria at Who Named It?

- "'Special' baby grew outside womb". BBC News. 2005-08-30. Archived from the original on 2007-02-12. Retrieved 2006-07-14.

- "Bowel baby born safely". BBC News. 2005-03-09. Archived from the original on 2007-02-11. Retrieved 2006-11-10.

- Zhang J, Li F, Sheng Q (2008). "Full-term abdominal pregnancy: a case report and review of the literature". Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation. 65 (2): 139–41. doi:10.1159/000110015. PMID 17957101. S2CID 35923100.

- "Rates of Cesarean Delivery -- United States, 1993". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2020-08-11.

- Betrán AP, Ye J, Moller AB, Zhang J, Gülmezoglu AM, Torloni MR (2016-02-05). "The Increasing Trend in Caesarean Section Rates: Global, Regional and National Estimates: 1990-2014". PLOS ONE. 11 (2): e0148343. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1148343B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0148343. PMC 4743929. PMID 26849801.

- Jurkovic D, Hillaby K, Woelfer B, Lawrence A, Salim R, Elson CJ (March 2003). "First-trimester diagnosis and management of pregnancies implanted into the lower uterine segment Cesarean section scar". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 21 (3): 220–7. doi:10.1002/uog.56. PMID 12666214. S2CID 27272542.

- Seow KM, Huang LW, Lin YH, Lin MY, Tsai YL, Hwang JL (March 2004). "Cesarean scar pregnancy: issues in management". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 23 (3): 247–53. doi:10.1002/uog.974. PMID 15027012. S2CID 36067188.

- "How to diagnose and treat cesarean scar pregnancy". Contemporary OBGyn. Retrieved 2020-08-11.

- Rotas MA, Haberman S, Levgur M (June 2006). "Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies: etiology, diagnosis, and management". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 107 (6): 1373–81. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000218690.24494.ce. PMID 16738166. S2CID 39198754.

- Ash A, Smith A, Maxwell D (March 2007). "Caesarean scar pregnancy". BJOG. 114 (3): 253–63. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01237.x. PMID 17313383. S2CID 34003037.

- Williams obstetrics. Cunningham, F. Gary (25th ed.). New York. 12 April 2018. ISBN 978-1-259-64432-0. OCLC 986236927.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Weimin W, Wenqing L (June 2002). "Effect of early pregnancy on a previous lower segment cesarean section scar". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 77 (3): 201–7. doi:10.1016/S0020-7292(02)00018-8. PMID 12065130. S2CID 28083933.

- Godin PA, Bassil S, Donnez J (February 1997). "An ectopic pregnancy developing in a previous caesarian section scar". Fertility and Sterility. 67 (2): 398–400. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(97)81930-9. PMID 9022622.

- Shu SR, Luo X, Wang ZX, Yao YH (2015-08-01). "Cesarean scar pregnancy treated by curettage and aspiration guided by laparoscopy". Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 11: 1139–41. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S86083. PMC 4529265. PMID 26345396.

- Monteagudo A, Calì G, Rebarber A, Cordoba M, Fox NS, Bornstein E, et al. (March 2019). "Minimally Invasive Treatment of Cesarean Scar and Cervical Pregnancies Using a Cervical Ripening Double Balloon Catheter: Expanding the Clinical Series". Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 38 (3): 785–793. doi:10.1002/jum.14736. PMID 30099757. S2CID 51966025.

- Lau S, Tulandi T (August 1999). "Conservative medical and surgical management of interstitial ectopic pregnancy". Fertility and Sterility. 72 (2): 207–15. doi:10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00242-3. PMID 10438980.

- Kemmann E, Trout S, Garcia A (February 1994). "Can We predict patients at risk for persistent ectopic pregnancy after laparoscopic salpingotomy?". The Journal of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists. 1 (2): 122–6. doi:10.1016/S1074-3804(05)80774-1. PMID 9050473.

- Mahboob U, Mazhar SB (2006). "Management of ectopic pregnancy: a two-year study". Journal of Ayub Medical College, Abbottabad. 18 (4): 34–7. PMID 17591007.

- "History, Diagnosis and Management of Ectopic Pregnancy" Archived 2015-10-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Long, Y; Zhu, H; Hu, Y; Shen, L; Fu, J; Huang, W (1 July 2020). "Interventions for non-tubal ectopic pregnancy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7: CD011174. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011174.pub2. PMC 7389314. PMID 32609376.

- Marret H, Fauconnier A, Dubernard G, Misme H, Lagarce L, Lesavre M, et al. (October 2016). "Overview and guidelines of off-label use of methotrexate in ectopic pregnancy: report by CNGOF". European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 205: 105–9. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.07.489. PMID 27572300.

- "eMedicine - Surgical Management of Ectopic Pregnancy: Article Excerpt by R Daniel Braun". Archived from the original on 2007-10-13. Retrieved 2007-09-17.

- Brady PC (October 2017). "New Evidence to Guide Ectopic Pregnancy Diagnosis and Management". Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 72 (10): 618–625. doi:10.1097/OGX.0000000000000492. PMID 29059454.

- Selo-Ojeme DO, Onwude JL, Onwudiegwu U (February 2003). "Autotransfusion for ruptured ectopic pregnancy". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 80 (2): 103–10. doi:10.1016/s0020-7292(02)00379-x. PMID 12566181. S2CID 24721754.

- Smith R (May 2006). "Research misconduct: the poisoning of the well". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 99 (5): 232–7. doi:10.1258/jrsm.99.5.232. PMC 1457763. PMID 16672756.

- "Ectopic Pregnancy". Archived from the original on 2015-10-14. Retrieved 2015-10-22.

- Bayer SR, Alper MM, Penzias AS (2011). The Boston IVF Handbook of Infertility: A Practical Guide for Practitioners Who Care for Infertile Couples, Third Edition. CRC Press. ISBN 9781841848181.

- Tulandi T, Tan SL, Tan SL, Tulandi T (2002). Advances in Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility: Current Trends and Developments. Informa Healthcare. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-8247-0844-3.

- Fernandez H, Capmas P, Lucot JP, Resch B, Panel P, Bouyer J (May 2013). "Fertility after ectopic pregnancy: the DEMETER randomized trial". Human Reproduction. 28 (5): 1247–53. doi:10.1093/humrep/det037. PMID 23482340.

- Fertility: assessment and treatment for people with fertility problems Archived 2013-02-23 at the Wayback Machine. NICE clinical guideline CG156 – Issued: February 2013

- Ohannessian A, Loundou A, Courbière B, Cravello L, Agostini A (September 2014). "Ovarian responsiveness in women receiving fertility treatment after methotrexate for ectopic pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Human Reproduction. 29 (9): 1949–56. doi:10.1093/humrep/deu174. PMID 25056087.

- Goyal LD, Tondon R, Goel P, Sehgal A (December 2014). "Ovarian ectopic pregnancy: A 10 years' experience and review of literature". Iranian Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 12 (12): 825–30. PMC 4330663. PMID 25709640.

- Fogarty S (March 2018). "Fertility Massage: an Unethical Practice?". International Journal of Therapeutic Massage & Bodywork. 11 (1): 17–20. PMC 5868897. PMID 29593844.

- Uthman E (2014). "Tubal pregnancy with embryo". WikiJournal of Medicine. 1 (2). doi:10.15347/wjm/2014.007.

- Delgado G. "Pro-Life Open Forum, Apr 10, 2013 (49min40s)". Catholic answers. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 2 September 2014.

- Pacholczyk T. "When Pregnancy Goes Awry". Making Sense Out of Bioethics (blog). National Catholic Bioethics Center. Archived from the original on 2011-11-23.

- Anderson, MA et al. Ectopic Pregnancy and Catholic Morality Archived 2016-04-18 at the Wayback Machine. National Catholic Bioethics Quarterly, Spring 2011

- "Registry Reports" (PDF). Volume XVI, Number 5. Ogden, Utah: ARDMS The Ultrasound Choice. October 1999. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-23. Retrieved 2011-06-22.

- "Miracle baby". Ogden, Utah: Utah News from KSL-TV. 1999-08-05. Archived from the original on 2011-09-30. Retrieved 2011-06-22.

- "Doctors hail 'miracle' baby". BBC News. 2009-09-10. Archived from the original on 2008-09-19.

- "Baby Born After Rare Ovarian Pregnancy". Associated Press. 2008-05-30. Archived from the original on June 3, 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-30.

- Cavanagh R (2008-05-30). "Miracle baby may be a world first". Archived from the original on 2008-05-30. Retrieved 2008-05-30.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ectopic pregnancy. |