Education in the Dominican Republic

In the Dominican Republic, education is free and compulsory at the elementary level, and free but non-mandatory at the secondary level. It is divided into four stages:

- preschool education (Nivel Inicial);

- primary education (Nivel Básico);

- secondary education (Nivel Medio);

- higher education (Nivel Superior).

| |

| General details | |

|---|---|

| Primary languages | Spanish |

| Literacy | |

| Total | 91.8% |

| Male | 91.2% |

| Female | 92.3% |

Literacy rates and school participation in the Dominican Republic has risen over the past years. Through these efforts, women have reported fast upward movement in social class partially due to increased education.[1] There have been numerous efforts to evaluate teachers, students, and facilities through examinations. Teachers in the Dominican Republic rate higher in multiple aspects than other countries in Latin America, however, still rank below many other countries.[2]

The school conditions vary based on whether the school is private, polytechnic, or public non-polytechnic, with decreasing quality facilities respectively. A very similar trend has been found in student performance.[3] Despite advances in the education system, there are still issues in regards to gender inequality, participation in the education system, and involvement of outside organizations.

Statistics

Literacy is defined by the NCES as having the ability to use printed and written information to function in society, to achieve one's goals, and to develop one's knowledge and potential.[4] According to the CIA World Factbook, 91.8% of the population over the age of 15 is considered literate. Literacy for females is listed at 92.3% while literacy for males is listed at 91.2%. Compared to the world, these numbers are higher than the average. Worldwide literacy is at 86.1%. For males, worldwide literacy is at 60.9% and for females world literacy is at 82.2%. The CIA world factbook also shows data on the school life expectancy of students in the Dominican Republic. For males, this life expectancy is at 13 years old which is slightly lower than the female school life expectancy of 14 years old.[5] The Dominican Republic National Education Profile reflects this showing higher levels of completion for both primary as well as secondary schools.[6]

[7] In 1980, the percent of the Dominican Republic's GDP that went towards education was 2%. This value dropped to 0.88% in 1990.[8] The education spending has since gone back up to around 4% of the GDP.[9]

Educational system

The Dominican Republic Education System is governed by four government organizations: the State Secretariat for Education (part of the executive branch of the government), in charge of the management and orientation of the education system; the Ministry of Education; the Ministry of Higher Education, Science and Technology; and the National Institute of Professional and Technical Training.[3]

The school year in Dominican Republic begins in mid-August and classes are held from Monday to Friday. The school year consists of two terms, which are separated by Christmas holidays in winter season, and an eight-week-long summer break. The year structure is summarized in the table below.

| Age | Grade | Educational establishments | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-4 | Maternal | Preschool Education (Nivel Inicial) |

Special School (Educación Especial) | ||||

| 4-5 | Kinder | ||||||

| 5-6 | Pre-primario | ||||||

| 6-7 | 1 | Elementary school (Nivel Básico) Mandatory Education | |||||

| 7-8 | 2 | ||||||

| 8-9 | 3 | ||||||

| 9-10 | 4 | ||||||

| 10-11 | 5 | ||||||

| 11-12 | 6 | ||||||

| 12-13 | 7 | ||||||

| 13-14 | 8 | ||||||

| 14-15 | 1 | High school / Secondary school (Nivel Medio, known popularly as Bachillerato) |

Institute of Technology (Politécnico) | ||||

| 15-16 | 2 | ||||||

| 16-17 | 3 | ||||||

| 17-18 | 4 | ||||||

Pre-primary school

The pre-primary stage of education in the Dominican Republic includes children under 6 years of age. There are three cycles of the pre-primary stage. The first cycle is for children ages 0–2 years old, the second cycle is for children 2–4 years old, and the third cycle is for children 4–6 years old. The Dominican Republic provides the last year of pre-primary education for families and this year is considered mandatory. The earlier years are not paid for by the Dominican Republic and are thus not required.[3]

Primary school

The Primary school stage of the Dominican Republic education system is eight years long and is designated for children ages 6–14. Primary education is compulsory and universal in the Dominican Republic. This is split up into two different cycles. The first cycle is grades 1-4 for children 6–10 years old and the second cycle is grades 5-8 and is for children 10–14 years old. Each grade level encompasses 10 months of teaching.[3]

Secondary school

Secondary school is provided by the Dominican Republic, however, this level of education is not compulsory. There are four years of schooling required to complete secondary school and it is for children age 14–18. The four years are split up into two cycles lasting two years each. The first cycle encompasses general and compulsory education. The second cycle has much more flexible curriculum and allows students to focus on either vocational and technical education or on the arts. The vocational and technical track prepares students for entry into certain professions and activities. This track focuses on teaching students about industry, agriculture, and other services. The arts education track focuses on developing the creativity of the students. Students can specialize into music, visual arts, performing arts, and applied arts. To graduate from secondary school, students must obtain a passing grade on national exams, pass their classes, and participate in a community service program.[3]

Higher education

The Dominican Republic has both public institutions as well as private institutions for higher education. There are 5 total public institutions: Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo (UASD), El Instituto Superior de Formación de Maestros Salomé Ureña, Fuerzas Armadas, Instituto Tecnológico de las Américas, and the Instituto Politécnico Loyola. The Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo is considered the state university while the other four public institutions are for more specialized areas. Beyond the public institutions, there are also 39 private institutions. Within these institutions, there are several tracks that students are able to take. Students can pursue Technical Studies which requires 2 years of schooling with a minimum of 85 credits. Graduate Studies requires a minimum of 140 credits. For students wishing to pursue a specialty in Graduate Studies, there is often an increased credit requirement. For architecture, veterinary, law, dentistry, pharmacy, and engineering, the requirement is 200 credits and at least four years of schooling. For medicine, the requirement is 5 years of schooling plus a one-year internship. After graduate studies, students also have the ability to pursue post-graduate education. For most specializations, there is a one-year and 20 credit minimum. To obtain a master's degree, students are generally required to complete 2 years of schooling encompassing 40 credits. For most students, their studies are generally extended by a half year to a year and a half of the required years of schooling.[3]

Adult education

.jpg.webp)

The adult education system provides education for adults who were unable to complete their education through the traditional route. This program encompasses literacy and primary schooling as well as secondary education. The track generally lasts about four years and can include professional training to provide adults with better skills for entering the workforce.[3]

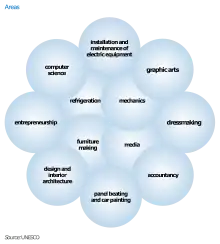

Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET)

Technical and vocational training (TVET) addresses multiple demands of an economic, social and environmental nature by helping young people and adults to develop the skills they need for employment, decent work and entrepreneurship, promoting equitable, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, and supporting transitions to green economies and environmental sustainability.[10]

The body in charge of providing vocational and technical education in the Dominican Republic is the Instituto Nacional de Formación Técnico Profesional (INFOTEP), which is funded by three sources:[10]

- 1% tax on payroll;

- 0.5% tax on employees bonuses;

- government funds.

INFOTEP runs 704 programmes aiming to promote skills development at several levels, with 104 of them having a special focus on vulnerable groups, such as those in very poor areas. The system relies on a dialogue between the government, employer federations and trade unions. Assessment studies are conducted in order to monitor the outcomes of the training provided.[10]

Sex education

Authorities in the Dominican Republic planned to instill a comprehensive sex education program in schools' curriculum, but it was not approved by the National Education Board.[11] [12] A study on sex education in developing countries noted that when developing resources for sex education, the context of the country and the local areas, such as literacy rates and school attendance, needs to be taken into consideration to ensure the effectiveness of the program.[13] From a study looking at sexual health of men in the Dominican Republic, 14% of males surveyed were found to have HIV antibodies.[14] Female sex workers are also at an increased risk of STI infections. Kerrigan identifies that there is a need for the development of educational resources regarding sex education in order to decrease the prevalence of STIs.[15] In a separate study in the Dominican Republic, those who received sex education were 1.72 times more likely to report having high HIV/AIDS knowledge. Additionally, those who received sex education were also 2.52 times more likely to use condoms during sex.[16] A study on sex education in developing countries noted that when developing resources for sex education, the context of the country and the local areas, such as literacy rates and school attendance, needs to be taken into consideration to ensure the effectiveness of the program.[17]

Special education

The Dominican Republic provides specialized education programs for children with special needs or physical disabilities to accommodate these needs.[3] The Dominican Association of Rehabilitation is one of the larger, government-funded special education institutions.[18] It has not only a school for special education, but programs for speech therapy, physical therapy, workshops, evaluation of disabilities, medical diagnostics and rehabilitation, and more.[18] While this service is provided, reports have found that 70% of children with a disability were currently not in school.[7]

Civic education

The United States has donated money to the Dominican Republic education system to help fund civic education classes. These classes were designed to increase students knowledge of civil society and democracy. The classes were found to increase positive feelings in students towards norms related to democracy. The study also found that the classes led students to foster feelings of distrust towards governmental bodies, especially the army and judicial system.[19]

Human rights education

A study instituted a 3-month course in human rights to a school in the Dominican Republic. The course focused both on global issues as well as local issues such as discrimination against Haitians. Bajaj notes that the course was not perfect, however, 100% of the students were able to explain what human rights were. Additionally, students were found to be more likely to be willing to stand up for others.[20]

Performance

Teacher performance

A study by Mihir, Manas and Aryan compared four countries in Central America on three indices concerning teachers and teacher quality. Of these four countries, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and the Dominican Republic, the Dominican Republic in general had higher ratings for their teachers, however, the article notes that there is much work that is needed to be done. The first index that was measured was whether the teachers were prepared for effective teaching. The study found that there were standards set for teachers. However, the study notes that the teachers in the Dominican Republic lacked an awareness of these standards and were thus unable to properly use them. In the Dominican Republic, there are 25 institutions that are dedicated towards training teachers. There is no structured system for the certification of teachers. Teachers are not required to obtain classroom practice prior to becoming a teachers.[2]

The second index studied was the process of attracting, hiring, and retaining teachers. It was found that there was a job application process that encompasses a logical reasoning exam, an exam on pedagogical knowledge and planning skills, and either an interview or oral exam. After being hired, teachers are coached during their first year of teaching. The education system collects data on student performance is often collected. The study does note that there is no usage of this knowledge towards increasing the quality of education. The researchers also found that teachers are paid a competitive salary. Part-time teachers are paid 32% higher than the average full-time worker and full-time teachers are paid 53% higher than the average university graduate who is working full-time.[2]

The third index researched whether schools managed for good performance. The researchers found that there were no regular teacher assessments and no incentives for teachers to teach in underprivileged areas. These underprivileged areas encompass rural and/or low income areas. There is a policy in place for poor performing teachers to undergo a year of training and re-evaluation, however, the researchers noted that this policy is rarely implemented in practice.[2]

Student performance

In 2005, a test was administered to students at grade levels 3, 4, and 5 to assess their competency in reading comprehension and mathematics curriculum from grade levels 1, 2, and 3. This test was called the Consorcio de Evaluación e Investigación Educativa (CEIE). In reading comprehension, the students were given 21 questions. Students were able to answer, on average, 7.37 questions on the test. The exam also found that girls performed better on the reading comprehension test than boys. In mathematics, students were given 35 questions. On average, the third grade students were able to answer 5.9 questions, the fourth grade students were able to answer 9.02 questions, and the fifth grade students were able to answer 11.94 questions. The researchers studying the exams claim that the results show that students were not learning the basics of reading comprehension and mathematics that they should be learning grades 1–3. The study also found that students at private schools performed better than students at public schools. Over 80% of children attend public schools.[3]

School conditions

Public schools are often overcrowded, lacking in textbooks and other instructional resources. The buildings themselves often have broken light fixtures, cracked walls, and other damage to the physical building. Polytechnic schools are considered public, however, they are also aided by another organization, usually a religious group. Polytechnic schools generally have higher quality facilities than public schools not linked to a secondary organization. Many schools in rural areas lack more infrastructure than public schools. Additionally, many schools in rural areas do not teach grades past the 6th grade. Private schools in general are of higher quality than public schools and often have resources and advantages that are not available to public schools. Private schools are able to pay their teachers a higher salary and provide higher quality learning resources such as textbooks for the students. These private schools generally serve students with parents from the upper middle class.[3]

School conditions have improved over the past years. Yovanny Gomez, who teaches at a school in the Dominican Republic, discusses in an interview how the school used to be filled with trash and lacking in air conditioning. This interview shows how there have been improvements in the school conditions.[21]

Studies have shown that many students have not been well prepared to face the challenges of university courses. This is shown by a large dropout rate of students who attend a university as well as a need for intense remedial work to prepare students for the rigor of college courses.[3]

Parent education

Some parent education programs have been implemented into the Dominican Republic to help improve the healthy development of children. Farrelly and McLennan produced a research study looking at the participation rates of parents in parent education programs as well as barriers that lead parents to not participate or be unable to complete the program. Their research found that, on average, parents only complete 59% of the course. However, they did find that reducing the time commitment and focusing on an intensive child nutrition component lead to higher completion rates. Common barriers that participants noted were a lack of money for transportation to the class, lack of childcare while the parent was at the class, and mothers who worked and were unable to take time off.[22]

McLennan produced a second research paper documenting efforts to implement a Canadian parent education program in the Dominican Republic. This program was focused on training parents on how to support the development of their children and focused on health, safety, and behavioral topics. The researchers trained local workers at a hospital to teach the program and adapted the curriculum that was used in Canada to be more relevant towards topics in the Dominican Republic.[23]

Issues

Participation

Educational opportunity in the Dominican Republic is important not only for increasing social status but also for health outcomes. De Tavarez and Andrade discuss how higher educational attainment in the Dominican Republic is negatively associated with the use of both alcohol and tobacco. This association is especially profound in tobacco use as there is a significant social gradient in tobacco use. Those with higher socioeconomic status, are less likely to smoke and education plays an important factor in socioeconomic status.[24]

Children in the Dominican Republic have listed education as one of their greatest concerns. Inequality in access to education is a primary concern for those living in the Dominican Republic as well as outside organizations such as UNICEF. UNICEF discusses how children in rural zones are much more likely to have a high rate of repetition and dropout. This is partially due to the distance that some children must travel to arrive at school.[25]

The average years of schooling of the adult population older than 15 is 7.43 years old. This value is less than the number of years required to complete primary schooling. One policy that was implemented to increase participation was to provide three different shifts of school that students could attend. Schools would provide a shift during the morning, afternoon, and evening to allow for students to continue working while also attending school. With these efforts, 75% of students complete grade 4, 63% complete grade 6, and 52% complete the full eight years of primary school. The Dominican Republic has higher levels of participation in the education system than many other Latin American countries.[3] Beyond attending school, the school days are 5 hours long, however, according to reports students learn for two hours and 40 minutes of those 5 hours. Thus, almost half of the school time is spent with children hanging "out in class while they're supposed to be studying."[21]

Gender inequality

Gender inequality for girls in the education system is not a significant issue in terms of participation. Attendance rates are slightly higher for girls between age 6-13 (87%) than for boys of the equivalent age (84%). As age increases, this difference becomes clearer as 40% of females aged 14–17 are enrolled and only 29% of males of the same age are enrolled. Thus, males are more likely than females to drop out of school.[3]

Major League Baseball

MLB scouts are especially prevalent in the Dominican Republic. Wasch et al. conducted a study looking into the effects that MLB recruiters have on boys in the Dominican Republic. The prospect of going into the MLB is often seen as the only way that boys, and consequently their families, can leave the Dominican Republic. Wasch discusses how many boys are pulled out of schooling to train with MLB recruiters and trainers to potentially make it into the MLB. However, only 1 in 40 every actually make it to an academy and of those who do make it only 3-5% get chosen to move up into the MLB. This system pulls boys out of the education system early and leaves them lacking a full education. Thus, these boys are less able to enter the workforce as productive members. Wasch offers two solutions for this problem: One is to create an international draft and hold international players to the same high school requirements that American players are held to. The second solution is for the MLB to create a child labor corporate code of conduct to ensure that teams are held accountable for the education of players and possible recruits.[26]

Steps for improvement

The World Bank has made steps to help fund improvements in the Dominican Republic education system. The World Bank has financed the Dominican Republic Early Childhood Education Project. This project has led to the construction of hundreds of new schools and technology centers, thousands of new classrooms, increased training for teachers as well as an increase in the number of teachers, and provision of resources to reinforce and enhance the quality of classrooms. The project is estimated to have directly benefited 52,000 children and 106,000 children indirectly.[27]

In 2015, The World Bank approved $50 million to help finance efforts to improve pre-university education. The money is aimed to "recruit and train primary and secondary school teachers; assess student learning in primary and secondary schools; evaluate early childhood development services and help decentralize public school management." The money is part of a National Pact for Education and the project will be implemented by the Ministry of Education (MINERD).[28]

See also

Sources

![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO. Text taken from Funding skills development: the private sector contribution, UNESCO, UNESCO. UNESCO.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO. Text taken from Funding skills development: the private sector contribution, UNESCO, UNESCO. UNESCO.

References

- "Gender Equality and Development: World Development Report 2012" (PDF). World Development Report. 2012.

- Sucre, Frederico; Fiszbein, Ariel (2015). "The State of Teacher Policies in Central America and the Dominican Republic". PREAL Policy Brief.

- OECD (2008). "Reviews of National Policies for Education: Dominican Republic 2008". Reviews of National Policies for Education.

- "National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL) - Definition of Literacy". National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- Central Intelligence Agency. "The World Factbook: Dominican Republic". The World Factbook. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- "Dominican Republic National Education Profile 2014 Update". Education Policy and Data Center. 2014.

- United States Agency for International Development (2013). "Dominican Republic Country Development Cooperation Strategy" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Kaplinsky, Raphael (1993). "Export Processing Zones in the Dominican Republic: Transforming manufactures into commodities". World Development. 21 (11): 1851–1865. doi:10.1016/0305-750x(93)90087-p.

- "DOMINICAN REPUBLIC: Four Percent for Education | Inter Press Service". www.ipsnews.net. Retrieved 2017-04-06.

- UNESCO (2018). Funding skills development: the private sector contribution. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-100269-4.

- Rosen, James E. “Formulating and Implementing National Youth Policy: Lessons from Bolivia and the DR.” Pathfinder International, 10 Jan. 2000, www.pathfinder.org/publications/formulating-implementing-national-youth-policy-lessons-bolivia-dr/.

- Parkinson, Joseph. "Humanae Vitae I: Pope Paul VI in Pastoral Mode." The Australasian Catholic Record 90.2 (2013): 185-95. ProQuest. Web. 11 Mar. 2020.

- Singh, Susheela; Bankole, Akinrinola; Woog, Vanessa (2005-11-01). "Evaluating the need for sex education in developing countries: sexual behaviour, knowledge of preventing sexually transmitted infections/HIV and unplanned pregnancy". Sex Education.

- Tabet, S. R.; de Moya, E. A.; Holmes, K. K.; Krone, M. R.; de Quinones, M. R.; de Lister, M. B.; Garris, I.; Thorman, M.; Castellanos, C. (1996-02-01). "Sexual behaviors and risk factors for HIV infection among men who have sex with men in the Dominican Republic". AIDS. 10 (2): 201–206. doi:10.1097/00002030-199602000-00011. ISSN 0269-9370. PMID 8838709.

- Kerrigan, Deanna; Ellen, Jonathan M.; Moreno, Luis; Rosario, Santo; Katz, Joanne; Celentano, David D.; Sweat, Michael (2003-02-14). "Environmental-structural factors significantly associated with consistent condom use among female sex workers in the Dominican Republic". AIDS. 17 (3): 415–423. doi:10.1097/00002030-200302140-00016. ISSN 0269-9370. PMID 12556696.

- Minaya, Jasmin; Owen-Smith, Ashli; Herold, Joan (2008-07-01). "The impact of sex education on HIV knowledge and condom use among adolescent females in the Dominican Republic". International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. 20 (3): 275–282. doi:10.1515/ijamh.2008.20.3.275. ISSN 0334-0139. PMID 19097565.

- Singh, Susheela; Bankole, Akinrinola; Woog, Vanessa (2005-11-01). "Evaluating the need for sex education in developing countries: sexual behaviour, knowledge of preventing sexually transmitted infections/HIV and unplanned pregnancy". Sex Education. 5 (4): 307–331. doi:10.1080/14681810500278089. ISSN 1468-1811.

- “Prensa.” Prensa, 2019, www.adr.org.do/.

- Finkel, Steve E; Sabatini, Christopher A; Bevis, Gwendolyn G (2000-11-01). "Civic Education, Civil Society, and Political Mistrust in a Developing Democracy: The Case of the Dominican Republic". World Development. 28 (11): 1851–1874. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00067-X.

- *, Monisha Bajaj (2004-03-01). "Human rights education and student self-conception in the Dominican Republic". Journal of Peace Education. 1 (1): 21–36. doi:10.1080/1740020032000178285. ISSN 1740-0201.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Manning, Katie (December 5, 2014). "Dominican Republic revamps failing education system". DW.com.

- Farrelly, A. C.; McLennan, J. D. (2009). "Participation in a Parent Education Programme in the Dominican Republic: Utilization and Barriers". Journal of Tropical Pediatrics.

- McLennan, John D. (2009). "Exporting a Canadian Education Program to the Dominican Republic". Public Health Nursing.

- De Tavarez, Michell Jimenez; Andrade, Flavia Cristina Drumond (2013). "Impact of Education on Tobacco Use and Alcohol Consumption in the Dominican Republic: A Social Gradient Perspective". International Journal of Health, Wellness & Society.

- "Boys and Girls of School-Going Age". UNICEF Dominican Republic.

- Wasch, Adam (2009). "Children Left Behind: The Effect of Major League Baseball on Education in the Dominican Republic". Texas Review of Entertainment & Sports Law.

- "Accessible and Quality Education for Young Children in Dominican Republic". The World Bank. September 19, 2013.

- Chapoy, Christelle (September 30, 2015). "Dominican Republic's Efforts to Improve Quality of Education Receive a New Boost". The World Bank.

.svg.png.webp)