People of the Dominican Republic

Dominicans (Spanish: Dominicanos) are people of the Dominican Republic. This identification may be historical, cultural, legal, or residential. For most Dominicans, several (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of being Dominican.

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 14 million Diaspora 2.9 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 9,341,916 (2017)[1] | |

| 2,082,857 (2018)[2] | |

| 158,393 (2015 census)[3] | |

| 68,000 (2010)[4] | |

| 43,000 (2017)[5] | |

| 23,130[6] | |

| 17,959 (2019)[7] | |

| 14,743 (2015)[8] | |

| 11,154[9] | |

| 11,091 (2015)[8] | |

| 8,688 (2015)[8] | |

| 8,095 (2015)[8] | |

| 2,942[10] | |

| Languages | |

| Dominican Spanish | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Roman Catholic;[11] Protestant | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Spanish · Portuguese · Canarians · Africans · Arabs · Amerindians · French · Germans · Italians · Jews · Levantines · Latin Americans | |

Dominican was historically the name for the inhabitants of the Captaincy General of Santo Domingo, the site of the first Spanish settlement in the Western Hemisphere. The origins of the Dominican Republic and its culture consists predominately in a European basis, with both African and native Taíno influences.[12]

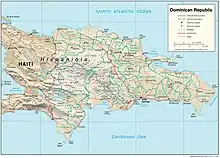

The majority of Dominicans reside in the Dominican Republic, while there is also a large Dominican diaspora, mainly in the United States and Spain. The total population of the Dominican Republic in 2016 was estimated by the National Bureau of Statistics of the Dominican Republic at 10.2 million, with 9.3 million of those being natives of the country, and the rest being of foreign origin.[1]

Name

Historically the Dominican Republic was known as Santo Domingo, the name of its present capital and its patron saint, Saint Dominic. Hence the residents were called "Dominicanos" (Dominicans). The revolutionaries named their newly independent country "La República Dominicana". It was often referred to as the "Republic of San Domingo" in English language 19th Century publications.

The first recorded use of the word "Dominican" is found in a letter written by King Phillip IV of Spain in 1625 to the inhabitants of the Captaincy General of Santo Domingo. In this letter, which was written before the arrival of French settlers on the Western side of the island, the King congratulates the Dominicans for their heroic efforts in defending the territory from an attack by a Dutch fleet. This letter can be found today in the "Archivo General de Indias" in Seville, Spain.

Another name that's been commonly used is "Quisqueyans". In the national anthem of the Dominican Republic the author uses the poetic term Quisqueyans instead of Dominicans. The word "Quisqueya" is a derivative from a native tongue of the Taino Indians which means, "Mother of the Lands." It is often used in songs as another name for the country.

History

Pre-European history

Prior to European colonization the inhabitants of the island were the Arawakan-speaking Taíno, a seafaring people who moved into Hispaniola from the north-east region of South America, displacing earlier inhabitants,[13] c. AD 650. The native Tainos divided the island into several chiefdoms and engaged in farming, fishing,[14] as well as hunting, and gathering.[13]

The Spaniards arrived in 1492. Columbus and his crew were the first Europeans to encounter the Taíno people. Columbus described the native Taínos as a physically tall, and well-proportioned people, with a noble character. After initially amicable relationships, the Taínos fought against the conquest, led by the female Chief Anacaona of Xaragua and her ex-husband Chief Caonabo of Maguana, as well as Chiefs Guacanagaríx, Guamá, Hatuey, and Enriquillo. The latter's successes gained his people an autonomous enclave for a time on the island. Within a few years after 1492 the population of Taínos had declined drastically, due to warfare and intermixing. Census records from 1514 reveal that at least 40% of Spanish men in Santo Domingo were married to Taino women,[15] and many present-day Dominicans have significant Taíno ancestry.[16][17]

European colonization

Christopher Columbus arrived on the island in December 5, 1492, during the first of his four voyages to the Americas. He claimed the land for Spain and named it La Española due to its diverse climate and terrain which reminded him of the Spanish landscape. In 1496 Bartholomew Columbus, Christopher's brother, built the city of Santo Domingo, Western Europe's first permanent settlement in the "New World." The colony thus became the springboard for the further Spanish conquest of America and for decades the headquarters of Spanish colonial power in the hemisphere.

In 1501, the colony began to import African slaves. In 1697, after decades of armed struggles with the French, Spain ceded the western coast of the island to France with the Treaty of Ryswick, whilst the Central Plateau remained under Spanish domain.

By the middle of the 18th century, the population was bolstered by European emigration from the Canary Islands, resettling the northern part of the colony and planting tobacco in the Cibao Valley, and importation of slaves was renewed. After 1700, with the arrival of new Spanish colonists, the African slave trade resumed. However, as industry moved from sugar to cattle ranching, racial and caste divisions became less important, eventually leading to a blend of cultures—Spanish, African, and indigenous—which would form the basis of national identity for Dominicans.[18] It is estimated that the population of the colony in 1777 was 400,000, of which 100,000 were European, 70,000 African, 100,000 European/indigenous mestizo, 60,000 African/indigenous mestizo, and 70,000 African/European.[19]

Dominican privateers captured British, Dutch, French and Danish ships throughout the 18th century.[20]

Independence

Santo Domingo attained independence as the Dominican Republic in 1844. In 1861, the Dominicans voluntarily returned to the Spanish Empire, but two years later they launched a war that restored independence in 1865.[21] A legacy of unsettled, mostly non-representative rule followed, capped by the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo from 1930 to 1961. Trujillo's regime carried out racially motivated killings of thousands of Haitians and committed crimes in the United States, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Venezuela, Guatemala, Costa Rica, and Mexico.[22] Trujillo was worth 800 million dollars (5.3 billion dollars today).[23] The Dominican Civil War of 1965 was ended by a United States-led intervention, and was followed by the authoritarian rule of Joaquín Balaguer, the leader from 1966–1978. Since that time, the Dominican Republic has moved steadily toward representative democracy.

Genetics and ethnicities

According to a 2015 genealogical DNA study of 27 Dominican individuals, their genetic makeup was estimated to be 52.15% European, 39.57% Sub-Saharan African, and 8.28% Native American and East Asian overall.[24]

In a 2014 population survey, 70.4% self-identified as mixed (mestizo/indio[lower-alpha 1] 58%, mulatto 12.4%), 15.8% black, 13.5% as white, and 0.3% as "other".[25][26] A different survey in 2006 reported 67.6% mulatto and mestizo, 18.3% black, and 13.6% white.[27] However, according to the electoral roll completed in 1996, 82.5% of the adult population were indio, 7.55% white, 4.13% black, and 2.3% mulatto.[28] Historically there has been a reluctance to expressly identify African ancestry, with most identifying or being identified as mestizo or indio rather than mulatto or black.[28][29]

Other groups in the country include the descendants of West Asians—mostly Lebanese, Syrians and Palestinians. A smaller, yet significant presence of East Asians (primarily ethnic Chinese and Japanese) can also be found throughout the population. Dominicans are also composed of Sephardic Jews that were exiled from Spain and the Mediterranean area in 1492 and 1497,[30] coupled with other migrations dating the 1700s[31] and during the Second World War [32] contribute to Dominican ancestry.[33][34] Some of the Sephardic Jews still presently reside in Sosúa while others are dispersed throughout the country.[35] The amount of known Jews (or those with genetic proof of Jewish ancestry and/or practiced Jewish customs/religion throughout generations) are close to 3,000; the exact number of Dominicans with Jewish lineages aren't known, however, because of the inter-mixing of the Jews and Dominicans over a period of more than five centuries.

In recent times, Dominican and Puerto Rican researchers identified in the current Dominican population the presence of genes belonging to the aborigines of the Canary Islands (commonly called Guanches).[36] These types of genes have also been detected in Puerto Rico.[37]

Immigration in the 20th and 21st centuries

In the twentieth century, many Chinese, Arabs (primarily from Lebanon and Syria), Japanese and to a lesser degree Koreans settled in the country, working as agricultural laborers and merchants. Waves of Chinese immigrants, the latter ones fleeing the Chinese Communist People's Liberation Army (PLA), arrived and worked in mines and building railroads. The current Chinese Dominican population totals 50,000.[38] The Arab community is also rising at an increasing rate.

In addition, there are descendants of immigrants who came from other Caribbean islands, including Saint Kitts and Nevis, Dominica, Antigua, St. Vincent, Montserrat, Tortola, St. Croix, St. Thomas, Martinique, and Guadeloupe. They worked on sugarcane plantations and docks and settled mainly in the cities of San Pedro de Macorís and Puerto Plata, they have a population of 28,000. There is an increasing number of Puerto Rican immigrants in and around Santo Domingo; they are believed to number at about 10,000. Before and during World War II 800 Jewish refugees moved to the Dominican Republic, and many of their descendants live in the town of Sosúa.[39] Nationwide, there are an estimated 100 Jews left.[40] Immigration from Europe and the United States is at an all-time high. 82,000 Americans (in 1999),[41] 40,000 Italians,[42] 1,900 French,[40] and 800 Germans.[40]

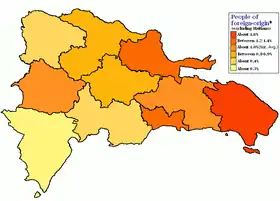

The 2010 Census registered 311,969 Haitians; 24,457 Americans; 6,691 Spaniards; 5,763 Puerto Ricans; and 5,132 Venezuelans.[43]

In 2012, the Dominican government made a survey of immigrants in the country and found that there were: 458,233 Haitian-born; 13,514 U. S.-born (excluding Puerto Rican-born); 6,720 Spanish-born; 4,416 Puerto Rican-born; 4,044 Italian-born; 3,643 Chinese-born; 3,599 French-born; 3,434 Venezuelan-born; 3,145 Cuban-born; 2,738 Colombian-born; 1,792 German-born; among others.[44][45][46]

In the second half of 2017, a second survey of foreign population was conducted in the Dominican Republic. The total population in the Dominican Republic was estimated at 10,189,895, of which 9,341,916 were Dominicans with no foreign background. According to the survey, the majority of the people with foreign background were of Haitian origin (751,080 out of 847,979, or 88.6%), breaking down as follows: 497,825 were Haitians born in Haiti, 171,859 Haitians born in the Dominican Republic and 81,590 Dominicans with a Haitian parent. Other main sources of foreign-born population were Venezuela (25,872), the United States (10,016), Spain (7,592), Italy (3,713), China (3,069), Colombia (2,642), Puerto Rico (2,356), and Cuba (2,024).[1]

Emigration

United States

The first recorded person of Dominican descent to migrate to what is now known as the United States was sailor-turned-merchant Juan Rodriguez. He arrived on Manhattan in 1613 from his home in Santo Domingo, which makes him the first non-Native American person to spend substantial time in the island. He also became the first Dominican, the first Latino and the first person with European (specifically Portuguese) and African ancestry to settle in what is present day New York City.[47]

Dominican emigration to the United States continued throughout the centuries. Recent research from the CUNY Dominican Studies Institute has documented some 5,000 Dominican emigrants who were processed through Ellis Island between 1892 and 1924.[48]

During the second half of the twentieth century, there were three significant waves of immigration to the United States. The first period began in 1961, when a coalition of high-ranking Dominicans, with assistance from the CIA, assassinated General Rafael Trujillo, the nation's military dictator.[49] In the wake of his death, fear of retaliation by Trujillo's allies, and political uncertainty in general, spurred migration from the island. In 1965, the United States began a military occupation of the Dominican Republic and eased travel restrictions, making it easier for Dominicans to obtain American visas.[50] From 1966 to 1978, the exodus continued, fueled by high unemployment and political repression. Communities established by the first wave of immigrants to the U.S. created a network that assisted subsequent arrivals. In the early 1980s, unemployment, inflation, and the rise in the value of the dollar all contributed to the third and largest wave of emigration from the island nation, this time mostly from the lower-class. Today, emigration from the Dominican Republic remains high, facilitated by the social networks of now-established Dominican communities in the United States.[51]

Besides the United States, significant numbers of Dominicans have also settled in Spain and in the nearby U.S. territory of Puerto Rico.

Dominican Emigration

| Rank | Country | Dominican Population |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,069,268 | |

| 2 | 158,393 | |

| 3 | 43,012 | |

| 4 | 14,972 | |

| 5 | 11,154 | |

| 6 | 11,127 | |

| 7 | 9,823 | |

| 8 | 9,383 | |

| 9 | 8,358 | |

| 10 | 5,110 | |

| 11 | 3,544 | |

| 12 | 3,441 | |

| 13 | 2,043 | |

| 14 | 1,819 | |

| 15 | 1,217 | |

| 16 | 1,104 | |

| 17 | 856 | |

| 18 | 745 | |

| 19 | 741 | |

| 20 | 709 | |

| 21 | 555 | |

| 22 | 410 | |

| 23 | 381 | |

| 24 | 363 | |

| 25 | 303 | |

| 26 | 289 | |

| 27 | 204 | |

| 28 | 187 | |

| 29 | 187 | |

| 30 | 185 | |

Dominican Immigration

| Rank | Country | Population in the Dominican Republic |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 336,729 | |

| 2 | 26,397 | |

| 3 | 7,221 | |

| 4 | 5,539 | |

| 5 | 3,927 | |

| 6 | 3,880 | |

| 7 | 3,687 | |

| 8 | 2,089 | |

| 9 | 1,698 | |

| 10 | 1,531 | |

| 11 | 1,517 | |

| 12 | 1,460 | |

| 13 | 1,243 | |

| 14 | 1,095 | |

| 15 | 1,068 | |

| 16 | 774 | |

| 17 | 659 | |

| 18 | 647 | |

| 19 | 606 | |

| 20 | 595 | |

| 21 | 577 | |

| 22 | 492 | |

| 23 | 492 | |

| 24 | 438 | |

| 25 | 433 | |

| 26 | 352 | |

| 27 | 313 | |

| 28 | 298 | |

| 29 | 273 | |

| 30 | 261 | |

Culture

The culture of the Dominican Republic, like its Caribbean neighbors, is a blend of the cultures of the European settlers, African slaves and settlers, and Taíno natives. Spanish is the official language. Other languages, such as English, French, German, Italian, and Chinese are also spoken to varying degrees. European, African, and Taíno cultural elements are most prominent in food, family structure, religion, and music. Many Arawak/Taíno names and words are used in daily conversation and for many foods native to the Dominican Republic.

Language

Spanish is the predominant language in the Dominican Republic; the local dialect is called Dominican Spanish, it closely resembles Canarian Spanish, and borrowed vocabularies from the Arawak language.[53] Schools are based on a Spanish educational model, with English and French being taught as secondary languages in both private and public schools. Haitian Creole is spoken by the population of Haitian descent.[54] There is a community of about 8,000 speakers of Samaná English in the Samaná Peninsula. They are the descendants of formerly-enslaved African Americans who arrived in the 19th century. Tourism, American pop culture, the influence of Dominican Americans, and the country's economic ties with the United States motivate other Dominicans to learn English.

Religion

The Dominican Republic is 80% Christian, including 57% Roman Catholic and 23% Protestant,.[55] Recent but small+scale immigration, as well as proselytizing, has brought other religions, with the following shares of the population: Spiritist: 1.2%,[56] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: 1.1%,[57] Buddhist: 0.10%, Baháʼí: 0.1%,[56] Islam: 0.02%, Judaism: 0.01%, Chinese folk religion: 0.1%,.[56]

Roman Catholicism was introduced by Columbus and Spanish missionaries. Religion wasn't really the foundation of their entire society, as it was in other parts of the world at the time, and most of the population didn't attend church on a regular basis. Nonetheless, most of the education in the country was based upon the Catholic religion, as the Bible was required in the curricula of all public schools. Children would use religious-based dialogue when greeting a relative or parent. For example, a child would say "Bless me, mother", and the mother would reply "May God bless you" {es}ven diga. The nation has two patroness saints: Nuestra Señora de la Altagracia (Our Lady Of High Grace) is the patroness of the Dominican people, and Nuestra Señora de las Mercedes (Our Lady Of Mercy) is the patroness of the Dominican Republic. The Catholic Church began to lose popularity in the late nineteenth century. This was due to a lack of funding, of priests, and of support programs. During the same time, the Protestant evangelical movement began to gain support. Religious tension between Catholics and Protestants in the country has been rare.

There have always been religious freedom throughout the entire country. Not until the 1950s were restrictions placed upon churches by Trujillo. Letters of protest were sent against the mass arrests of government adversaries. Trujillo began a campaign against the church and planned to arrest priests and bishops who preached against the government. This campaign ended before it was even put into place, with his assassination.

Judaism appeared in the Dominican Republic in the late 1930s. During World War II, a group of Jews escaping Nazi Germany fled to the Dominican Republic and founded the city of Sosúa. It has remained the center of the Jewish population since.[58]

Cuisine

Dominican cuisine is predominantly made up of a combination of Spanish, Native American, and a little African influences over the last few centuries. The typical cuisine is quite similar to what can be found in other Latin American countries, but many of the names of dishes are different. One breakfast dish consists of eggs and mangú (mashed, boiled plantain). For heartier versions, these are accompanied by deep-fried meat (typically Dominican salami) and/or cheese. Similarly to Spain, lunch is generally the largest and most important meal of the day. Lunch usually consists of rice, some type of meat (chicken, beef, pork, or fish), beans, plantains, and a side portion of salad. "La Bandera" (literally, The Flag), the most popular lunch dish, consists of meat and red beans on white rice. There is a famous soup "Sancocho" a typical national soup made with seven kinds of variety of meats.

Dominican cuisine usually accommodates all the food groups, incorporating meat or seafood; rice, potatoes, or plantains; and is accompanied by some other type of vegetable or salad. However, meals usually heavily favor starches and meats over dairy products and vegetables. Many dishes are made with sofrito, which is a mix of local herbs and spices sautéed to bring out all of the dish's flavors. Throughout the south-central coast, bulgur, or whole wheat, is a main ingredient in quipes or tipili (bulgur salad). Other favorite Dominican dishes include chicharrón, yuca, casabe, and pastelitos (empanadas), batata, pasteles en hoja, (ground-roots pockets)[59] chimichurris, plátanos maduros (ripe plantain), and tostones.

Some treats Dominicans enjoy are arroz con dulce (or arroz con leche), bizcocho dominicano (lit. Dominican cake), habichuelas con dulce (sweet creamed beans), flan, frío frío (snow cones), dulce de leche, and caña (sugarcane).

The beverages Dominicans enjoy include Morir Soñando, rum, beer, Mama Juana, batida (smoothie), jugos naturales (freshly squeezed fruit juices), mabí, and coffee.[60]

Music and dance

Musically, the Dominican Republic is known for the creation of the musical style called merengue,[61] a type of lively, fast-paced rhythm and dance music consisting of a tempo of about 120 to 160 beats per minute (it varies wildly) based on musical elements like drums, brass, and chorded instruments, as well as some elements unique to the music style of the DR. It includes the use of the tambora (Dominican drum), accordion, and güira. Its syncopated beats use Latin percussion, brass instruments, bass, and piano or keyboard. Between 1937 and 1950 the merengue music was promoted internationally, by some Dominicans groups like, Billo's Caracas Boys, Chapuseaux and Damiron Los Reyes del Merengue, Joseito Mateo and others. Later on it was more popularized via television, radio and international media, well-known merengue singers include singer/songwriter Juan Luis Guerra, Fernando Villalona, Eddy Herrera, Sergio Vargas, Toño Rosario, Johnny Ventura, and Milly Quezada and Chichí Peralta. Merengue became popular in the United States, mostly on the East Coast, during the 1980s and 90s,[62] when many Dominican artists, among them Victor Roque y La Gran Manzana, Henry Hierro, Zacarias Ferraira, Aventura, Milly, and Jocelyn Y Los Vecinos, residing in the U.S. (particularly New York City) started performing in the Latin club scene and gained radio airplay. The emergence of bachata, c along with an increase in the number of Dominicans living among other Latino groups in New York, New Jersey, and Florida have contributed to Dominican music's overall growth in popularity.[63]

Bachata, a form of music and dance that originated in the countryside and rural marginal neighborhoods of the Dominican Republic, has become quite popular in recent years. Its subjects are often romantic; especially prevalent are tales of heartbreak and sadness. In fact, the original name for the genre was amargue ("bitterness", or "bitter music", or blues music), until the rather ambiguous (and mood-neutral) term bachata became popular. Bachata grew out of and is still closely related to, the pan-Latin American romantic style called bolero. Over time, it has been influenced by merengue and by a variety of Latin American guitar styles.

Salsa music has had a great deal of popularity in the country. During the late 1960s Dominican musicians like Johnny Pacheco, creator of the Fania All Stars played a significant role in the development and popularization of the genre.

Particularly among the young, a genre that has been growing in popularity in recent years in the Dominican Republic is Dominican rap. Also known as Rap del Patio ("yard rap") it is rap music created by Dominican crews and solo artists. Originating in the early 2000s with crews such as Charles Family, successful rappers such as Lapiz Conciente, Vakero, Toxic Crow, and R-1 emerged. The youth have embraced the music, sometimes over merengue, merengue típico, bachata, as well as salsa, and, most recently, reggaeton. Dominican rap differs from reggaeton in the fact that Dominican rap does not use the traditional Dem Bow rhythm frequently used in reggaeton, instead of using more hip hop-influenced beats. As well, Dominican rap focuses on urban themes such as money, women, and poverty, similarly to American rap.

Fashion

In only seven years, the Dominican Republic's fashion week has become the most important event of its kind in all of the Caribbean and one of the fastest-growing fashion events in the entire Latin American fashion world. The country boasts one of the ten most important design schools in the region, La Escuela de Diseño de Altos de Chavón, which is making the country a key player in the world of fashion and design.

World-famous fashion designer Oscar de la Renta was born in the Dominican Republic in 1932 and became a US citizen in 1971. He studied under the leading Spaniard designer Cristóbal Balenciaga and then worked with the house of Lanvin in Paris. Then by 1963, de la Renta had designs carrying his own label. After establishing himself in the US, de la Renta opened boutiques across the country. His work blends French and Spaniard fashion with American styles.[64][65] Although he settled in New York, de la Renta also marketed his work in Latin America, where it became very popular, and remained active in his native Dominican Republic, where his charitable activities and personal achievements earned him the Juan Pablo Duarte Order of Merit and the Order of Cristóbal Colón.[65]

Sports

Baseball is by far the most popular sport in the Dominican Republic.[66] After the United States, the Dominican Republic has the second-highest number of Major League Baseball (MLB) players. Some of these players have been regarded among the best in the game. Historically, the Dominican Republic has been linked to MLB since Ozzie Virgil, Sr. became the first Dominican to play in the league. Among the outstanding MLB players born in the Dominican are: Manny Ramirez, David Ortiz, Vladimir Guerrero, Juan Soto, Bartolo Colon, Robinson Cano, Jose Ramirez, Nelson Cruz, Pedro Martínez, Albert Pujols, Adrián Beltré, José Reyes, José Bautista, Hanley Ramírez, Miguel Tejada, Juan Marichal, Rafael Furcal and Sammy Sosa.

Olympic gold medalist and world champion over 400 m hurdles Félix Sánchez hails from the Dominican Republic, as does current defensive end for the San Diego Chargers (National Football League [NFL]), Luis Castillo. Castillo was the cover athlete for the Spanish language version of Madden NFL 08.[67]

The National Basketball Association (NBA) also has had players from the Dominican Republic, like Charlie Villanueva, Al Horford and Francisco García. Boxing is one of the more important sports after baseball, and the country has produced scores of world-class fighters and world champions.

Holidays

| Date | Name | |

|---|---|---|

| January 1 | New Year's Day | Non-working day. |

| January 6 | Catholic day of the Epiphany | Movable. |

| January 21 | Día de la Altagracia | Non-working day. Patroness Day (Catholic). |

| January 26 | Duarte's Day | Movable. Founding Father. |

| February 27 | Independence Day | Non-working day. National Day. |

| (Variable date) | Holy Week | Working days, except Good Friday. A Catholic holiday. |

| May 1 | International Workers' Day | Movable. |

| Last Sunday of May | Mother's Day | |

| (Variable date) | Catholic Corpus Christi | Non-working day. A Thursday in May or June (60 days after Easter Sunday). |

| August 16 | Restoration Day | Non-working day. |

| September 24 | Virgen de las Mercedes | Non-working day. A Patroness Day (Catholic) |

| November 6 | Constitution Day | Movable. |

| December 25 | Christmas | Non-working days. |

Notes:

- Non-working holidays are not moved to another day.

- If a movable holiday falls on Saturday, Sunday or Monday then it is not moved to another day. If it falls on Tuesday or Wednesday, the holiday is moved to the previous Monday. If it falls on Thursday or Friday, the holiday is moved to the next Monday.

Notable people

See also

Sources

- The Mulatto Republic: Class, Race, and Dominican National Identity. April J. Mayes. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2014. ISBN 978-0-8130-4919-9

Notes

- The term "indio" in the Dominican Republic is not associated with people of indigenous ancestry but people of mixed ancestry or skin color between light and dark

References

- Segunda Encuesta Nacional de Inmigrantes en la República Dominicana [ENI-2017] - Versión resumida del Informe General [Second National Survey of Immigrants in the Dominican Republic [ENI-2017] - Summary version of the General Report] (PDF) (Report) (in Spanish). Santo Domingo: Oficina Nacional de Estadística. June 2017. p. 48. ISBN 978-9945-015-17-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-06-04. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- US Census Bureau. "Hispanic or Latino Origin by Specific Origin".

- "El Nuevo Diario - Los dominicanos en el exterior".

- "Dominican Immigrants in Puerto Rico". Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved 2018-05-09.

- "Dominican Immigrants in the United States". 2018-04-09. Archived from the original on 2018-04-26. Retrieved 2018-04-25.

- "Ethnic Origin, both sexes, age (total), Canada, 2016 Census – 25% Sample data". Canada 2016 Census. Statistics Canada. 2019-02-20. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- "Inmigrantes en Chile llegan a 1.251.225 personas y venezolanos superan a peruanos por primera vez". Archived from the original on 2019-04-26. Retrieved 2019-04-26.

- "The Dominican Republic's migration landscape" (PDF). www.oecd-ilibrary.org. 2017. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- "República Dominicana - Emigrantes totales 2017". Archived from the original on 2019-04-07. Retrieved 2019-04-07.

- AUSTRIA, STATISTIK. "Bevölkerungsstruktur". www.statistik.at. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- "Central America :: Dominican Republic — The World Factbook". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2020-01-22.

- Esteva Fabregat, Claudio «La hispanización del mestizaje cultural en América» Revista Complutense de Historia de América, Universidad Complutense de Madrid. p. 133 (1981)

- Luna Calderón, Fernando (December 2002). "ADN Mitocondrial Taíno en la República Dominicana" [Taíno Mitochondrial DNA in the Dominican Republic] (PDF). Kacike (in Spanish) (Special). ISSN 1562-5028. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 1, 2008.

- "Dominican Republic". Encarta. Microsoft Corporation. Archived from the original on November 14, 2007. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- Ferbel Azcarate, Pedro J. (December 2002). "Not Everyone Who Speaks Spanish is from Spain: Taíno Survival in the 21st Century Dominican Republic" (PDF). KACIKE: The Journal of Caribbean Amerindian History and Anthropology (Special). ISSN 1562-5028. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 17, 2004. Retrieved September 24, 2009.

- Guitar, Lynne (December 2012). "Documenting the Myth of Taíno Extinction" (PDF). Kacike (Special). ISSN 1562-5028. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- Martínez Cruzado, Juan Carlos (December 2002). "The Use of Mitochondrial DNA to Discover Pre-Columbian Migrations to the Caribbean: Results for Puerto Rico and Expectations for the Dominican Republic" (PDF). Kacike (Special). ISSN 1562-5028. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 5, 2016. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- P. J. Ferbel (2002). "La sobrevivencia de la cultura Taína en la República Dominicana" [Survival of the Taino culture in the Dominican Republic] (in Spanish). suncaribbean.net. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- "World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples – Dominican Republic". Minority Rights Group International – MRGI. 2007. Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- "Corsairs of Santo Domingo a socio-economic study, 1718-1779" (PDF).

- "Central America :: Dominican Republic — The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". Cia.gov.

- "Documentary Heritage on the Resistance and Struggle for Human Rights in the Dominican Republic, 1930-1961" (PDF).

- Rogozinski 258

- Montinaro, Francesco; et al. (24 March 2015). "Unravelling the hidden ancestry of American admixed populations". Nature Communications. 6. See Supplementary Data. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.6596M. doi:10.1038/ncomms7596. PMC 4374169. PMID 25803618.

- "Central America :: Dominican Republic — The World Factbook". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2020-01-22.

- "Dominican Republic - Settlement patterns". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2020-04-15. Retrieved 2020-02-01.

- Fuente: Encuesta Latin American Public Opinion Project, LAPOP,"La variable étnico racial en los censos de población en la República Dominicana" (in Spanish). Oficina Nacional de Estadística. p. 20. Archived from the original on 29 July 2013.

- Moya Pons, Frank (2010). "Evolución de la población dominicana". In Frank Moya Pons (ed.). Historia de la República Dominicana [History of the Dominican Republic] (in Spanish). 2. Santo Domingo: CSIC Press. pp. 50–53. ISBN 978-84-00-09240-5. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- Howard, David (2001). Coloring the Nation: Race and Ethnicity in the Dominican Republic. Oxford, United Kingdom: Signal Books. pp. 69–70. ISBN 1-902669-11-8. Archived from the original on 2 April 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- "The Exile of the Jews due to the Spanish Inquisition". Archived from the original on 2011-08-13. Retrieved 2013-05-15.

- "Jews migration in the 1700s". Archived from the original on 2013-10-02. Retrieved 2013-05-15.

- "Jews migration to the Dominican Republic to seek refuge from the Holocaust". Archived from the original on 2013-01-13. Retrieved 2013-05-15.

- "A partial, brief summary of Jews in the Dominican Republic". Archived from the original on 2013-06-26. Retrieved 2013-05-15.

- "Dominican Republic-Jews". Archived from the original on 2013-10-01. Retrieved 2013-05-15.

- "Municipal Map of the Dominican Republic showing the Historical Ancestry". Archived from the original on 2013-08-19. Retrieved 2013-05-15.

- "Un estudio descubre la presencia de genes guanches en la República Dominicana". Archived from the original on 2018-12-16. Retrieved 2018-12-16.

- "La Comunidad » DOCUMENTALES GRATIS » UN ESTUDIO DEL GENOMA TAINO Y GUANCHE. ADN o DNA. Primera parte". February 6, 2010. Archived from the original on February 6, 2010.

- "The Chinese Community and Santo Domingo's Barrio Chino". Archived from the original on 2017-08-07. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- "CCNY Jewish Studies Class to Visit Dominican Village that Provided Refuge to European Jews During World War II" (Press release). City College of New York. Archived from the original on 2011-05-10. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- "Joshua Project People-in-Country Profile". Archived from the original on 2010-02-08. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- "American Citizens Living Abroad by Country" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 19, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- "* INFORM *; Giovani italiani nel Centro America e Caraibi". Archived from the original on 2012-08-04. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- Oficina Nacional de Estadística (June 2012). "IX Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda 2010: Volumen 1 (Informe General)" (PDF) (in Spanish). Santo Domingo. pp. 99–103. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- Martínez, Darlenny (2 May 2013). "Estudio: en RD viven 534,632 extranjeros". El Caribe (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

Según la Primera Encuesta Nacional de Inmigrantes de la República Dominicana (ENI-2012), (...) Después de Haití, explica la investigación, las 10 naciones de donde proceden más inmigrantes son Estados Unidos, con 13,524; España, con 6,720, y Puerto Rico, con 4,416. Además Italia, con 4,040; China, con 3,643; Francia, con 3,599; Venezuela, con 3,434; Cuba con 3,145 inmigrantes; Colombia con 2,738 y Alemania con 1,792.

- "Primera Encuesta Nacional de Inmigrantes (ENI-2012)" Archived 2015-06-21 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish). Santo Domingo: Instituto Nacional de Estadística (former 'Oficina Nacional de Estadística') & United Nations Population Fund. p. 63. 2012.

- Juan Bolívar Díaz (4 May 2013). "RD país de emigrantes más que de inmigrantes" (in Spanish). Hoy. Archived from the original on 21 August 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- "Dominican Who was City's First Settler to Get Street". Voices Of NY. December 11, 2012. Archived from the original on October 30, 2013. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- "Preview of Research Findings October 22: Dominican Immigration Through Ellis Island". CUNY Dominican Studies Institute News. Archived from the original on 2015-03-19. Retrieved 2014-01-23.

- "Justice Department Memo, 1975" (PDF). National Security Archive. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-06-27. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

- Morrison, Thomas K.; Sinkin, Richard (1982). "International Migration in the Dominican Republic: Implications for Development Planning". International Migration Review. 16 (4): 819–36. doi:10.2307/2546161. JSTOR 2546161. PMID 12265312.

- "Social Studies In Action: Migration From Latin America". www.learner.org. Archived from the original on 2008-09-13. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

- "República Dominicana - Inmigración". Datosmacro.com (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2019-04-01. Retrieved 2019-04-07.

- Henríquez Ureña, Pedro (1940). El Español en Santo Domingo (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Instituto de Filología de la Universidad de Buenos Aires.

- Baker, Colin; Prys Jones, Sylvia, eds. (1998). Encyclopedia of Bilingualism and Bilingual Education. p. 389. ISBN 978-1-85359-362-8. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- "Religion in Latin America: Widespread Change in a Historically Catholic Region" (PDF). November 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- "Religious Freedom Page". Archived from the original on 2008-06-17. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- "Country Profiles > Dominican Republic". Archived from the original on October 17, 2009.

- Haggerty, Richard (1989). "Dominican Republic - Religion". Dominican Republic: A Country Study. U.S. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 2006-09-23. Retrieved 2006-05-21.

- "Pasteles en hoja (Ground-roots pockets) - Dominican Cooking". 2002-12-20. Archived from the original on 2008-10-21. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- "Dominican Republic Cuisine by Hispaniola.com". Archived from the original on 2009-12-12. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

- Harvey, Sean (January 2006). The Rough Guide to The Dominican Republic. Rough Guides. pp. 376–7. ISBN 978-1-84353-497-6.

- Harvey, Sean (January 2006). The Rough Guide to The Dominican Republic. Rough Guides. p. 375. ISBN 978-1-84353-497-6.

- Harvey, Sean (January 2006). The Rough Guide to The Dominican Republic. Rough Guides. pp. 378. ISBN 978-1-84353-497-6.

- Fashion: Oscar de la Renta (Dominican Republic) Archived 2013-01-16 at the Wayback Machine WCAX.com – Retrieved October 31, 2012.

- Oscar de la Renta Archived 2013-01-20 at the Wayback Machine. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved October 31, 2012.

- Harvey, Sean (January 2006). The Rough Guide to The Dominican Republic. Rough Guides. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-84353-497-6.

- Shanahan, Tom (2007-03-24). "San Diego Hall of Champions - Sports at Lunch, Luis Castillo and Felix Sanchez". San Diego Hall of Champions. Archived from the original on June 5, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-29.

External links

- Consejo Nacional de Población y Familia (National Council of Population and Family) – The demographics department of the Dominican government