Falkland Islands sovereignty dispute

Sovereignty over the Falkland Islands (Spanish: Islas Malvinas) is disputed by Argentina and the United Kingdom.

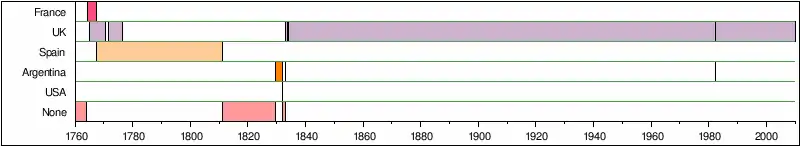

| February 1764 – April 1767 | |

| January 1765 – July 1770 | |

| April 1767 – February 1811 | |

| September 1771 – May 1774 | |

| February 1811 – August 1829 | None |

| August 1829 – December 1831 | |

| December 1831 – January 1832 | |

| January–December 1832 | None |

| December 1832 – January 1833 | |

| January–August 1833 | |

| August 1833 – January 1834 | None |

| January 1834 – April 1982 | |

| April–June 1982 | |

| June 1982 – present |

The British claim to sovereignty dates from 1690, when they were the first to land on the islands,[1] and the United Kingdom has exercised de facto sovereignty over the archipelago almost continuously since 1833. Argentina has long disputed this claim, having been in control of the islands for a few years prior to 1833. The dispute escalated in 1982, when Argentina invaded the islands, precipitating the Falklands War.

Contemporary Falkland Islanders overwhelmingly prefer to remain British. They gained full British citizenship with the British Nationality (Falkland Islands) Act 1983, after British victory in the Falklands War.

Historical basis of the dispute

French settlement

France was the first country to establish a permanent settlement in the Falkland Islands, with the foundation of Port Saint Louis on East Falkland by French explorer Louis Antoine de Bougainville, in 1764.[2] The French colony consisted of a small fort and some settlements with a population of around 250. The islands were named after the Breton port of St. Malo as the Îles Malouines, which remains the French name for the islands. In 1766, France agreed to leave the islands to Spain, with Spain reimbursing de Bougainville and the St. Malo Company for the cost of the settlement.[3][4] France insisted that Spain maintain the colony in Port Louis to prevent Britain from claiming the title to the Islands, and Spain agreed.[5]

Spanish settlement

In 1493 Pope Alexander VI issued a Papal bull, Inter caetera, dividing the New World between Spain and Portugal. The following year, the Treaty of Tordesillas between those countries agreed that the dividing line between the two should be 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands.[6] The Falklands lie on the western (Spanish) side of this line.

Spain made claims that the Falkland Islands were held under provisions in the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht which settled the limits of the Spanish Empire in the Americas. However, the treaty only promised to restore the territories in the Americas held prior to the War of the Spanish Succession. The Falkland Islands was not held at the time, and were not mentioned in the treaty. When Spain discovered the British and French colonies on the Islands, a diplomatic row broke out among the claimants. In 1766, Spain and France, who were allies at the time, agreed that France would hand over Port Saint Louis, and Spain would repay the cost of the settlement. France insisted that Spain maintain the colony in Port Louis and thus prevent Britain from claiming the title to the Islands and Spain agreed.[5] Spain and Great Britain enjoyed uneasy relations at the time, and no corresponding agreement was reached.[4]

The Spanish took control of Port Saint Louis and renamed it Puerto Soledad in 1767. On 10 June 1770, a Spanish expedition expelled the British colony at Port Egmont, and Spain took de facto control of the Islands. Spain and Great Britain came close to war over the issue, but instead, concluded a treaty on 22 January 1771, allowing the British to return to Port Egmont with neither side relinquishing sovereignty claims.[7] The British returned in 1771 but withdrew from the islands in 1774, leaving behind a flag and a plaque representing their claim to ownership, and leaving Spain in de facto control.[8]:25

From 1774 to 1811, the islands were ruled as part of the Viceroyalty of the River Plate. In that period, 18 governors were appointed to rule the islands. In 1777, Governor Ramon de Carassa was ordered to destroy the remains at Port Egmont. The British plaque was removed and sent to Buenos Aires.[5]:51

Spanish troops remained at Port Louis, known then as Port Soledad, until 1811[9] when Governor Pablo Guillen Martinez was called back to Montevideo as the revolutionary forces spread through the continent. He left behind a plaque claiming sovereignty for Spain.[4][10]

British settlements

The British first landed on the Falklands in 1690, when Captain John Strong sailed through Falkland Sound, naming this passage of water after Anthony Cary, 5th Viscount of Falkland, the First Lord of the Admiralty at that time. The British were keen to settle the islands as they had the potential to be a strategic naval base for passage around Cape Horn.[11] In 1765, Captain John Byron landed on Saunders Island. He then explored the coasts of the other islands and claimed the archipelago for Britain. The following year, Captain John MacBride returned to Saunders Island and constructed a fort named Port Egmont. The British later[12]:30–31 discovered the French colony at Port Saint Louis (founded 1764), initiating the first sovereignty dispute.[4]

In 1770 a Spanish military expedition was sent to the islands after authorities in Buenos Aires became aware of the British colony.[13] Facing a greater force, the British were expelled from Port Egmont. The colony was restored a year later following British threats of war over the islands;[4] However, in 1774, economic pressures leading up to the American Revolutionary War forced Great Britain to withdraw from the Falklands along with many of its other overseas settlements.[14] They left behind a plaque asserting British sovereignty over the islands.[8] Although there was no British administration in the islands, British and American sealers routinely used them to hunt for seals, also taking on fresh water as well as feral cattle, pigs and even penguins for provisions. Whalers also used the islands to shelter from the South Atlantic weather and to take on fresh provisions.

The Government of the United Provinces of the River Plate attempted to control the islands through commerce, granting fishing and hunting rights to Jorge Pacheco in 1824. Pacheco's partner Luis Vernet established a toehold in the islands in 1826 and a fledgling colony in 1828. He also visited the British consulate in 1826, 1828 and 1829 seeking endorsement of his venture and British protection for his settlement in the event of their returning to the islands.[12]:50[15][16] After receiving assurances from the British minister chargé d'affaires, Sir Woodbine Parish, Vernet provided regular reports to the British on the progress of his enterprise. He expressed the wish that, in the event of the British returning to the islands, the British Government would take his settlement under their protection; Parish duly passed this wish on to London.[12]:52 In 1829, he sought a naval vessel from the United Provinces to protect his colony but as none were available he was appointed Military and Civil Commander, prompting British protests.[17][18] Attempts to regulate fishing and sealing lead to conflict with the United States and the Lexington raid of 1831.[19] With the colony in disarray, Major Esteban Mestivier was tasked to set up a penal colony but was murdered in a mutiny shortly after arriving in 1832.[20] Protests at Mestivier's appointment received no response and so the British dispatched a naval squadron to re-establish British rule.[21]

After the Government of the United Provinces of the River Plate appointed Vernet as governor in 1829, Parish protested to Buenos Aires, which merely acknowledged the protest. Britain protested again when Vernet announced his intention to exercise exclusive rights over fishing and sealing in the islands. (Similar protests were received from the American representative, who protested at the curtailment of established rights and stated that the United States did not recognise the jurisdiction of the United Provinces over the islands.)[22] Vernet continued to provide regular reports to Parish throughout this period.[12]:52

The raid of the USS Lexington in December 1831 combined with the United Provinces assertions of sovereignty were the spur for the British to establish a military presence on the islands.

On 2 January 1833, Captain James Onslow, of the brig-sloop HMS Clio, arrived at the Spanish settlement at Port Louis to request that the Argentine flag be replaced with the British one, and that the Argentine administration leave the islands. While Argentine Lt. Col. José María Pinedo, commander of the Argentine schooner Sarandí, wanted to resist,[23]:90 his numerical disadvantage was obvious, particularly as a large number of his crew were British mercenaries who were unwilling to fight their own countrymen.[23] Such a situation was not unusual in the newly independent states in Latin America, where land forces were strong, but navies were frequently quite undermanned. He protested verbally,[24]:26 but departed without a fight on 5 January. The islands have since continued under British rule except during the Falklands War.

After their return in 1833, the British did not attempt to develop the islands as a colony. Initially, plans were based upon the settlers remaining in Port Louis, supported by the annual visit of a warship. Vernet's deputy, Matthew Brisbane, returned in March 1833 aboard the sealer Rapid during the visit of HMS Beagle.[25] He took charge of the settlement and was encouraged to further Vernet's business interests provided he did not seek to assert Argentine Government authority.[23][26][27] Argentines have claimed that the population of Puerto Luis was expelled after the British return,[28][29][30] but historical records shows that only four members of the settlement chose to leave.[31][32]

Following the Gaucho murders in August 1833, the Falklands were administered as a military outpost with the few remaining residents of Vernet's colony. The first British Resident, Lt Smith, was established in 1834 and under his administration and initiative the settlement recovered and began to prosper. Lt Smith's commanding officer was not enthusiastic about Royal Navy officers engaged in encouraging commerce, and rebuked Smith. Smith resigned, and subsequent residents allowed the settlement to stagnate.

In 1841, General Rosas offered to relinquish any Argentine territorial claims in return for relief of debts owed to Barings Bank in the City of London. The British Government chose to ignore the offer.[33]

In Britain, the Reform Act 1832 had extended the vote to more British citizens, including members of the free-trade merchant class who saw economic opportunity in opening up markets in South America. The British Board of Trade saw establishing new colonies and trade with them as a way to expand manufacturing jobs. The Foreign and Colonial Offices agreed to take on the Falklands as one of these colonies, if only to prevent colonisation by others.[34] In May 1840, a permanent colony was established in the Falklands. A British colonial administration was formed in 1842. This was expanded in 1908, when in addition to South Georgia, claimed in 1775, and the South Shetland Islands, claimed in 1820, the UK unilaterally declared sovereignty over more Antarctic territory south of the Falklands, including the South Sandwich Islands, the South Orkney Islands, and Graham Land, grouping them into the Falkland Islands Dependencies.

In 1850, the Arana-Southern Treaty otherwise known as the Convention of Settlement was signed between the United Kingdom and Argentina. It has been argued by several authors on both sides of the dispute that Argentina tacitly gave up her claim by failing to mention it and ceasing to protest over the Falklands. Between December 1849 and 1941, the Falklands were not mentioned in the President's Messages to Congress.

Following the introduction of the Antarctic Treaty System in 1959 the Falkland Islands Dependencies were reduced to include just South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. Territory south of the 60th parallel was formed into a new dependency, the British Antarctic Territory, which overlaps claims by Argentina (Argentine Antarctica) and Chile (Antártica Chilena Province).

In 1976 the British Government commissioned a study on the future of the Falklands, which looked at the ability of the islands to sustain themselves, and the potential for economic development. The study was led by Lord Shackleton, son of the Antarctic explorer, Ernest Shackleton. Argentina reacted with fury to the study and refused to allow Lord Shackleton permission to travel to the islands from Argentina, forcing the British to send a Royal Navy ship to transport him to the islands. In response Argentina severed diplomatic links with the UK. An Argentine naval vessel later fired upon the ship carrying Shackleton as he visited his father's grave in South Georgia.

Shackleton's report found that contrary to popular belief, the Falkland Islands actually produced a surplus by its economic activities, and was not dependent on British aid to survive. However the report stressed the need for a political settlement if further economic growth was to be achieved, particularly from the exploitation of any natural resources in the water around the islands.

Argentine settlements

Argentina declared its independence from Spain in 1816, although this was not then recognised by any of the major powers. The UK informally recognised Argentine independence on 15 December 1823, as the "province of Buenos Aires",[35] and formally recognised it on 2 February 1825,[36] but, like the US, did not recognise the full extent of the territory claimed by the new state.[37]

In October 1820, the frigate Heroína, under the command of American privateer Colonel David Jewett, arrived in Puerto Soledad after an eight-month voyage and with most of her crew incapacitated by scurvy and other disease. A storm had severely damaged the Heroína and had sunk a Portuguese ship pirated by Jewett called the Carlota.[38] The captain sought assistance from the British explorer James Weddell to put the ship into harbour. Weddell reported that only thirty seamen and forty soldiers out of a complement of 200 were fit for duty, and that Jewett slept with pistols over his head following an attempted mutiny. On 6 November 1820, Jewett raised the flag of the United Provinces of the River Plate and claimed possession of the islands for the new state. Weddell reported that the letter he received from Jewett read:[39]

Sir, I have the honour to inform you of the circumstance of my arrival at this port, commissioned by the supreme government of the United Provinces of South America to take possession of these islands in the name of the country to which they naturally appertain. In the performance of this duty, it is my desire to act towards all friendly flags with the most distinguished justice and politeness. A principal object is to prevent the wanton destruction of the sources of supply to those whose necessities compel or invite them to visit the islands, and to aid and assist such as require it to obtain a supply with the least trouble and expense. As your views do not enter into contravention or competition with these orders, and as I think mutual advantage may result from a personal interview, I invite you to pay me a visit on board my ship, where I shall be happy to accommodate you during your pleasure. I would also beg you, so far as comes within your sphere, to communicate this information to other British subjects in this vicinity. I have the honour to be, Sir Your most obedient humble Servant, Signed, Jewett, Colonel of the Navy of the United Provinces of South America and commander of the frigate Heroína.

Many modern authors report this letter as the declaration issued by Jewett.[23] Jewett's report to the government of Buenos Aires does not mention any claim to the Falkland Islands,[40] and news of the claim reached Argentina by way of the United States and Europe in November 1821, over a year after the event.[41]

In 1823, the Buenos Aires government granted land on East Falkland to Jorge Pacheco, a businessman from Buenos Aires who owed money to the merchant Luis Vernet.[42] A first expedition travelled to the islands the following year, arriving on the East Falkland on 2 February 1824. This was deemed as "a failure" by author Mary Cawkell:[8]:31 "A week after arrival in February 1824, Areguati sent a despairing letter to Pacheco."[12]:47 Its leader was Pablo Areguatí, who brought with him 25 gauchos. Ten days later Areguatí wrote that the colony was perishing because the horses they had brought were too weak to be used, thus they could not capture wild cattle and their only other means of subsistence was wild rabbits. On 7 June, Areguatí left the islands, taking with him 17 gauchos. On 24 July, the remaining eight gauchos were rescued by the Susannah Anne, a British sealer. After the failure, Pacheco agreed to sell his share to Vernet.[42]

A second attempt, in 1826, sanctioned by the British[12]:48 (but delayed until winter by a Brazilian blockade), also failed after arrival in the islands.[12]:52 In 1828, the Buenos Aires government granted Vernet all of East Falkland, including all its resources, with exemption from taxation for 20 years, if a colony could be established within three years. He took settlers, including British Captain Matthew Brisbane, and before leaving once again sought permission from the British Consulate in Buenos Aires.[12]:50 The British asked for a report on the islands, and Vernet asked for British protection should they return.[12][43]

On Vernet's return to the Falklands, Puerto Soledad was renamed Puerto Luis. The Buenos Aires government, headed by General Juan Galo de Lavalle, appointed Vernet "Political and Military Commander" in a decree of 13 June 1829. The British objected to this as an Argentine attempt to foster political and economic ties to the islands. One of Vernet's first acts was to curb seal hunting on the islands to conserve the dwindling seal population. In response, the British consul at Buenos Aires protested the move and restated the claim of his government. Islanders were born during this period (including Malvina María Vernet y Saez, Vernet's daughter).[43]

Vernet later seized three American ships, the Harriet, Superior and Breakwater, for disobeying his restrictions on seal hunting. The Breakwater escaped to raise the alarm and the Superior was allowed to continue its work for Vernet's benefit. Property on board the Harriet was seized and Vernet returned with it to Buenos Aires for the captain to stand trial. The American Consul in Argentina protested Vernet's actions and stated that the United States did not recognise Argentine sovereignty in the Falklands. The consul dispatched a warship, the USS Lexington, to Puerto Luis to retake the confiscated property.

By 1831, the colony was successful enough to be advertising for new colonists, although a report by the captain of the Lexington suggests that the conditions on the islands were quite miserable.[44][45] The captain of the Lexington in his report asserts that he destroyed the settlement's powder store and spiked the guns; however it was later claimed that during the raid the Argentine settlement at Puerto Luis was destroyed. Upon leaving to return to Montevideo, the captain of the Lexington declared the islands to be res nullius (nobody's property).[43] (Darwin's visit in 1833 confirmed the squalid conditions in the settlement, although Captain Matthew Brisbane, Vernet's deputy, later insisted that these were the result of the attack by the Lexington.)[26] Vernet had returned to Buenos Aires in 1831 before the attack, and resigned as governor. An interim governor, Esteban José Francisco Mestivier, was appointed by the Buenos Aires Government. He arrived at Puerto Luis with his family aboard the schooner Sarandí in October 1832.[43] Mestivier's appointment again drew protests from the British consul in Buenos Aires.

The Sarandí, under the command of its captain, José María Pinedo, then began to patrol the surrounding seas. Upon its return to Puerto Luis on 29 December 1832, the Sarandí found the colony in an uproar. In Pinedo's absence there had been a mutiny led by a man named Gomila; Mestivier had been murdered and his wife raped. The captain of the French vessel Jean Jacques had meanwhile provided assistance, disarming and incarcerating the mutineers. Pinedo dispatched the mutineers to Buenos Aires with the British schooner Rapid. Gomila was condemned to exile, while seven other mutineers were executed.

On 2 January 1833, Captain John Onslow arrived and delivered written requests that Pinedo lower the Argentine flag in favour of the British one, and that the Argentine administration leave the islands. Pinedo asked if war had been declared between Argentina and the United Kingdom; Onslow replied that it had not. Nonetheless, Pinedo, heavily outmanned and outgunned, left the islands under protest, with the Argentine flag being lowered by British officers and delivered to him. Back on the mainland, Pinedo faced court martial; he was suspended for four months and transferred to the army, though he was recalled to the navy in 1845.

Sovereignty dispute

The American sealing vessels Harriet and Breakwater that had been seized by Vernet (see above) brought claims against their insurers, and in 1839 these claims reached the Supreme Court of the United States in the case of Williams v. Suffolk Insurance Company.[46] The insurers argued that Vernet was the legal governor of the Falkland Islands, the sealing was therefore illegal and so they ought not to have to pay. The ruling of the Supreme Court was:

The government of the United States having insisted, and continuing to insist, through its regular executive authority, that the Falkland Islands do not constitute any part of the dominions within the sovereignty of Buenos Ayres, and that the seal fishery at those islands is a trade free and lawful to the citizens of the United States, and beyond the competence of the Buenos Ayres government to regulate, prohibit, or punish, it is not competent for a circuit court of the United States to inquire into and ascertain by other evidence the title of the government of Buenos Ayres to the sovereignty of the Falkland Islands.

The 1850 Convention of Settlement, otherwise known as the Arana-Southern Treaty, which did not mention the islands, agreed to restore "perfect relations of friendship" between the two countries. There were no further protests until 1885, when Argentina included the Falkland Islands in an officially sponsored map.. In 1888, Argentina made an offer to have the matter subject to arbitration, but this was rejected by the British Government.. Other than the protest lodged in 1885, the British Government did not acknowledge any further protests by Argentina until the 1940s, although the official position of the Argentine Government is that "During the first half of the twentieth century, the successive Argentine governments made it standard practice to submit protests to the United Kingdom".[47] The Argentine Government does not identify these annual protests, but authors such as Roberto Laver[48] claim at least "27 sovereignty claims, both to Britain, domestically in Argentina and to international bodies". In International Law, territorial claims are usually considered defunct if there is a gap of 50 years or more between protests over sovereignty.[49]

Following World War II, the British Empire declined, and many colonies in Asia, Africa and the Caribbean gained their independence. Argentina saw this as an opportunity to push its case for gaining sovereignty over the Falkland Islands, and raised the issue in the United Nations, first stating its claim after joining the UN in 1945. Following this claim, the United Kingdom offered to take the dispute over the Falkland Islands Dependencies to mediation at the International Court of Justice in The Hague (1947,[50] 1948[51] and 1955[51]). On each occasion Argentina declined.

In 1965, the United Nations passed a resolution calling on the UK and Argentina to proceed with negotiations on finding a peaceful solution to the sovereignty question which would be "bearing in mind the provisions and objectives of the Charter of the United Nations and of General Assembly resolution 1514 (XV) and the interests of the population of the Falkland Islands (Malvinas)."[52]

A series of talks between the two nations took place over the next 17 years until 1981, but failed to reach a conclusion on sovereignty. Although the sovereignty discussions had some success in establishing economic and transport links between the Falklands and Argentina, there was no progress on the question of sovereignty of the islands.

After the two nations signed the Communications Agreement of 1971,[53] whereby external communications would be provided to the Falkland Islands by Argentina, the Argentine Air Force broke the islands' airways isolation by opening an air route with an amphibious flight from Comodoro Rivadavia with Grumman HU-16B Albatross aircraft operated by LADE, Argentina's military airline. In 1972, after an Argentine request, the United Kingdom agreed to allow Argentina to construct a temporary air strip near Stanley. On 15 November 1972 a temporary runway was inaugurated with the first arrival of a Fokker F-27; subsequent flights arrived twice weekly. Flights were improved in 1978 with Fokker F-28 jets, after the completion of a permanent runway funded by the British Government. This service, the only air connection to the islands, was maintained until the 1982 war.[54][55][56]

Also YPF, which was then the Argentine national oil and gas company, was in charge of supplying the island regularly.[57]

Whilst maintaining the British claim, the British Government considered a transfer of sovereignty less than two years before the outbreak of war.[58] However, the British Government had limited room for manoeuvre owing to the strength of the Falkland Islands lobby in the Houses of Parliament. Any measure that the Foreign Office suggested on the sovereignty issue was loudly condemned by the islanders, who reiterated their determination to remain British. This led to the British Government maintaining a position that the right to self-determination of the islanders was paramount. But Argentina did not recognise the rights of the islanders, and so negotiations on the sovereignty issue remained at a stalemate.[59]

In 1966, a group of Argentine nationalists hijacked an Aerolineas Argentinas DC-4 and forced it to land in Port Stanley, in an unsuccessful attempt to seize the islands for Argentina.

In 1976, Argentina landed an expedition in Southern Thule,[60] an island in the South Sandwich Islands which at that time was part of the Falkland Islands Dependency. The landing was reported in the UK only in 1978, although the British government issued a rejection of the notion of sending a force of Royal Marines to dismantle the Argentine base Corbeta Uruguay.

There was a more serious confrontation in 1977 when the Argentine Navy cut off the fuel supply to Port Stanley Airport, and said they would no longer fly the Red Ensign in Falklands waters. (Traditionally ships in a foreign country's waters would fly the country's maritime flag as a courtesy.) The British Government suspected Argentina would attempt another expedition in the manner of its Southern Thule operation. James Callaghan, the British Prime Minister, ordered the dispatch of a nuclear submarine, HMS Dreadnought and the frigates Alacrity and Phoebe to the South Atlantic, with rules of engagement set in the event of a clash with the Argentine navy. The British even considered setting up an exclusion zone around the islands, but this was rejected in case it escalated matters. These events were not made public until the parliamentary debates in 1982 during the Falklands War.

Falklands War

.svg.png.webp)

The Falklands War of 1982 was the largest and most severe armed conflict over the sovereignty of the islands. It started following the occupation of South Georgia by Argentine scrap merchants whose number included some Argentine Marines. However, the UK had also reduced its presence in the Islands by announcing the withdrawal of HMS Endurance, the Royal Navy's icebreaker ship and only permanent presence in the South Atlantic. The UK had also denied Falkland Islanders full British citizenship under the British Nationality Act 1981.

In 1982, Argentina was in the midst of a devastating economic crisis and large-scale civil unrest against the repressive military junta that was governing the country. On 2 April, with Argentine Navy commander-in-chief Admiral Jorge Anaya as the main architect and supporter of the operation, a combined Argentine amphibious force invaded the Islands. Immediately, the UK severed diplomatic ties with Argentina, and began to assemble a task force to retake the Islands. A diplomatic offensive began, to gain support for economic and military sanctions. The United Nations Security Council issued Resolution 502 calling on Argentina to withdraw forces from the Islands and on both parties to seek a diplomatic solution.[61] Another resolution[62] called for an immediate ceasefire, but this was vetoed by both the United States and the United Kingdom. The European Community condemned the invasion and imposed economic sanctions on Argentina, although several EC states expressed reservations about British policy in this area.[63] France and West Germany also temporarily suspended several military contracts with the Argentine military. The United States supported mediated talks, via Secretary of State Alexander Haig, and initially took a neutral stance, although in private substantial material aid was made available to the UK from the moment of invasion. The US publicly supported the UK's position following the failure of peace talks.

The British Task Force began offensive action against Argentina on 23 April 1982 and recaptured South Georgia after a short naval engagement. The operation to recover the Falkland Islands began on 1 May, and after fierce naval and air engagements an amphibious landing was made at San Carlos Bay on 21 May. On 14 June the Argentine forces surrendered, and control of the islands returned to the UK. Two Royal Navy ships then sailed to the South Sandwich Islands and expelled the Argentine military from Thule Island, leaving no Argentine presence in the Falkland Islands Dependencies.

Post-war

Following the 1982 war, the British increased their presence in the Falkland Islands. RAF Mount Pleasant was constructed. This allowed fighter jets to be based on the islands and strengthened the UK's ability to reinforce the Islands at short notice. The military garrison was substantially increased and a new garrison was established on South Georgia. The Royal Navy South Atlantic patrol was strengthened to include both HMS Endurance and a Falkland Islands guard ship.[64]

As well as this military build-up, the UK also passed the British Nationality (Falkland Islands) Act 1983, which granted full British citizenship to the islanders. To show British commitment to the islands, high-profile British dignitaries visited the Falklands, including Margaret Thatcher, the Prince of Wales and Princess Alexandra, The Hon Lady Ogilvy. The UK has also pursued links to the islands from Chile, which had provided help to British Forces during the Falklands War. LATAM now provides a direct air link to Chile from Mount Pleasant.[65]

In 1985 the Falkland Islands Dependencies, comprising at that time the island groups of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, and Shag Rocks and Clerke Rocks, became a distinct British overseas territory — South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands.

Under the 1985 constitution the Falkland Islands Government (FIG) became a parliamentary representative democratic dependency, with the governor as head of government and representative of the Queen. Members of the FIG are democratically elected, the governor is effectively a figurehead. Theoretically the governor has the power under the 1985 constitution to exercise executive authority, in practice he is obliged to consult the Executive Council in the exercise of his functions. The main responsibilities of the governor are external affairs and public services.[66] Effectively under this constitution, the Falkland Islands are self-governing with the exception of foreign policy, although the FIG represents itself at the United Nations Special Committee on Decolonisation as the British Government no longer attends.

Relations between the UK and Argentina remained hostile after 1982, and diplomatic relations were restored in 1989. Although the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution calling for the UK and Argentina to return to negotiations over the Islands' future,[67] the UK ruled out any further talks over the Islands' sovereignty. The UK has also maintained controls on arms exports to Argentina,[68] although these were relaxed in 1998.[69]

Relations between the UK and Argentina improved further in the 1990s. In 1998, Carlos Menem, the President of Argentina, visited London, where he reaffirmed his country's claims to the Islands, although he stated that Argentina would use only peaceful means for their recovery. In 2001, Tony Blair, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, visited Argentina and said he hoped the UK and Argentina could resolve their differences that led to the 1982 war. However, no talks on sovereignty took place during the visit, and Argentina's President Néstor Kirchner stated that he regarded gaining sovereignty over the islands as a "top priority" of his government.[70]

Argentina renewed claims in June 2006, citing concern over fishing and petroleum rights; the UK changed from annually granting fishing concessions, to granting a 25-year concession.[71] On 28 March 2009, UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown stated that there was "nothing to discuss" with Cristina Kirchner, the Argentine president, over sovereignty of the islands, when they met in Chile on his pre-2009 G-20 London Summit world tour.[72] On 22 April 2009 Argentina presented to the UN a formal claim to an area of the continental shelf encompassing the Falklands, South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands, and parts of Antarctica, citing 11 years worth of maritime survey data.[73] The UK quickly protested these claims.[74]

In February 2010, in response to British plans to begin drilling for oil,[75] the Argentine government announced that ships travelling to the Falklands (as well as South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands) would require a permit to use Argentine territorial waters. The British and Falkland governments stated that this announcement did not affect the waters surrounding the islands.[76][77] Despite the new restrictions, Desire Petroleum began drilling for oil on 22 February 2010, about 54 nautical miles (100 km, 62 mi) north of the Islands.[78]

In 2011 the Mercosur bloc agreed to close ports to ships flying the Falkland Islands flags, while British-flagged ships would continue to be allowed.[79]

In March 2013 the Falkland Islanders voted overwhelmingly in a referendum for the territory to remain British. Argentina dismissed this referendum.[80][81] The British Government urged Argentina and other countries to respect the islanders' wishes.[82]

Current claims

Argentina

The Argentine government argues that it has maintained a claim over the Falkland Islands since 1833, and renewed it as recently as December 2012.[83] It considers the archipelago part of the Tierra del Fuego Province, along with South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands.

Supporters of the Argentine position make the following claims:

- That sovereignty of the islands was transferred to Argentina from Spain upon independence in 1816,[84] a principle known as uti possidetis juris.

- That the British dropped their claim by acquiescence by not protesting the many years of pacific and effective Spanish occupation, after the abandonment of Port Egmont.[85][86][87] :34–35

- That, in addition to uti possidetis juris, sovereignty was obtained when the islands were formally claimed in Argentina's name in 1820, followed by Argentina's confirmation and effective occupation from 1826 to 1833.[88][89][90]

- That the establishment of British de facto rule on the Falklands in 1833 (referred to as an "act of force" by Argentina) was illegal under international law, and this has been noted and protested by Argentina on 17 June 1833 and repeated in 1841, 1849, 1884, 1888, 1908, 1927, 1933, 1946, and yearly thereafter in the UN.[91][92]

- That the principle of self-determination is not applicable since the current inhabitants are not aboriginal and were brought to replace the Argentine population (see below).[93]

- That the principle of self-determination does not apply to this sovereignty question because, as Argentina argues, the current inhabitants are a "transplanted population", of British character and nationality, not a distinct "people" as required by external self-determination doctrine.[93][94]

- That self-determination is further rendered inapplicable due to the disruption of the territorial integrity of Argentina that began with a forceful removal of its authorities in the islands in 1833, thus there is a failure to comply with an explicit requirement of UN Resolution 1514 (XV).[93][94]

- That the UN ratified this inapplicability of self-determination when the Assembly rejected proposals to condition sovereignty on the wishes of the islanders.[93]

- That the islands are located on the continental shelf facing Argentina, which would give them a claim, as stated in the 1958 UN Convention on the Continental Shelf.[95]

- That Great Britain was looking to extend its territories in the Americas as shown with the British invasions of the Río de la Plata years earlier.[96]

The Nootka Sound Conventions

In 1789, both the United Kingdom and Spain attempted settlement in the Nootka Sound, on Vancouver Island. On 25 October 1790, these two Kingdoms approved the Nootka Sound Convention. The Conventions included provisions recognising that the coasts and islands of South America colonised by Spain at the time were Spanish, and that areas south of the southernmost settlements were off limits to both countries, provided (in a secret article) that no third party settled there either. The conventions were unilaterally repudiated by Spain in 1795 but implicitly revived by the Treaty of Madrid in 1814.

The sixth article of the convention states:[97]

It is further agreed with respect to the eastern and western coasts of South America and the islands adjacent, that the respective subjects shall not form in the future any establishment on the parts of the coast situated to the south of the parts of the same coast and of the islands adjacent already occupied by Spain; it being understood that the said respective subjects shall retain the liberty of landing on the coasts and islands so situated for objects connected with their fishery and of erecting thereon huts and other temporary structures serving only those objects.

Whether or not this affected sovereignty over the islands is disputed. The British argue that the agreement did not affect the respective claims and only stipulated that neither party would make further establishments on the coasts or "adjacent" islands already held by Spain.[98] Argentina argues that "the islands adjacent" includes the Falklands and that the UK renounced any claim by the agreements.[99]

Constitution of Argentina

The Argentine claim is included in the transitional provisions of the Constitution of Argentina as amended in 1994:[100][101]

The Argentine Nation ratifies its legitimate and non-prescribing sovereignty over the Malvinas, Georgias del Sur and Sandwich del Sur Islands and over the corresponding maritime and insular zones, as they are an integral part of the National territory. The recovery of these territories and the full exercise of sovereignty, respecting the way of life for its inhabitants and according to the principles of international law, constitute a permanent and unwavering goal of the Argentine people.

In addition, Argentina demonstrates its claim to the islands by stating they are part of its Tierra del Fuego Province.

United Kingdom

In 1964 the Argentine government raised the matter at the United Nations in a sub-committee of the Special Committee on the situation with regard to the implementation of the UN Declaration of the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples. In reply, the British Representative on the committee declared that the British Government held that the question of sovereignty over the islands was "not negotiable". Following a report by the Special Committee, UN General Assembly Resolution 2065 was passed on 16 December 1965. In its preamble it referred to the UN's "cherished aim to bring colonialism to an end everywhere", and invited both nations to proceed with negotiations to find a peaceful solution bearing in mind "the interests of the population of the Falkland Islands (Malvinas)".[52][102]

In January 1966 the British Foreign Secretary, Michael Stewart, visited Buenos Aires when the Argentine claim to the islands was raised with him, following which, in July, a preliminary meeting was held in London, where the British delegation "formally rejected" the Argentine Ambassador's suggestion that the UK's occupation of the Islands was illegal.[102]

On 2 December 1980, Nicholas Ridley, Minister of State at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, stated in the House of Commons: "We have no doubt about our sovereignty over the Falkland Islands... we have a perfectly valid title".[102] The British government regards the right of the islanders to self-determination as "paramount"[102][103] and rejects the idea of negotiations over sovereignty without the islanders' consent.[104] Supporters of the British position argue:

- That self determination is a universal right enshrined in UN charter, and applies in the case of the Falkland Islanders.[105][106]

- That the 2013 referendum, in which 99.8% of Falklands voters voted to remain a British Overseas Territory on a 92% turnout, was an exercise in self-determination that "demonstrated beyond all doubt" the islanders' views on the dispute; and that the result should be respected by all other countries including Argentina.[107][108][109]

- That the UK both claimed and settled the islands in 1765 before Argentina existed.[98]

- That the 1771 Anglo-Spanish agreement preserved the claims of both Spain and Britain, not Spain alone.[41]

- That the UK abandoned its settlement in 1774 due to economic pressures, but left a plaque behind proving sovereignty was not relinquished.[98]

- That the Nootka Sound Convention only stipulated against further establishments and did not affect existing claims to sovereignty.[98]

- That uti possidetis juris "is not a universally accepted principle of international law" and Argentina could not inherit the islands upon independence anyway as Spain did not have de facto control since 1811.[110]

- That Argentina's attempts to colonise the islands were ineffectual and there was no indigenous or settled population before British settlement.[106]

- That in 1833 an Argentine garrison was expelled but the civilian residents were encouraged to stay.[41]

- That the islands have been continuously and peacefully occupied by the UK since 1833, with the exception of "2 months of illegal occupation" by Argentina.[106]

- That the Arana-Southern Treaty of 1850 (the 'Convention of Settlement'), ended all possible claims by Argentina on the Falkland Islands.[41][111]

- That Argentine leaders indicated in the 1860s that there was no dispute between Argentina and the UK, and that Argentine maps printed between 1850 and 1884 did not show the islands as part of Argentina.[41]

- That the UN Special Committee on Decolonization resolutions calling for negotiations "are flawed because they make no reference to the Islanders' right to choose their own future".[106]

- The European Union Treaty of Lisbon ratifies that the Falkland Islands belong to the United Kingdom.[103]

Falkland Islands Constitution

The Constitution of the Falkland Islands, which came into force on 1 January 2009, claims the right to self-determination, specifically mentioning political, economic, cultural, and other matters.[112]

International and regional views

Argentina has pursued an aggressive diplomatic agenda, regularly raising the issue and seeking international support. South American countries have expressed support for the Argentine position and called for negotiations to restart at regional summits.[113] The People's Republic of China has backed Argentina's sovereignty claim, reciprocating Argentina's support of the PRC claim to Taiwan, denying their independence.[114] Conversely, the Republic of China on Taiwan acknowledges British sovereignty and ignores Argentina's sovereignty claim.[115]

Since 1964, Argentina has lobbied its case at the Decolonization Committee of the UN, which annually recommends dialogue to resolve the dispute. The UN General Assembly has passed several resolutions on the issue. In 1988, the General Assembly reiterated a 1965 request that both countries negotiate a peaceful settlement to the dispute and respect the interests of the Falkland Islanders and the principles of UN GA resolution 1514.[116]

The United States and the European Union recognise the de facto administration of the Falkland Islands and take no position over their sovereignty;[114][117] however, the EU classifies the islands as an overseas country or territory of the UK. During the UK's tenue as an EU member, the islands were subject to EU law in some areas until 2020 when the UK left the EU. The Commonwealth of Nations listed the islands as a British Overseas Territory in their 2012 yearbook.[118] At the OAS summits Canada has continued to state its support for the islanders' right to self-determination.[119][120]

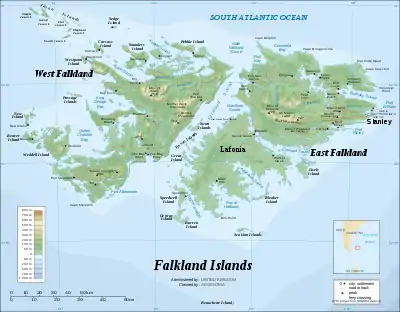

Map of the Islands, with British names .svg.png.webp)

Map of the Islands, with Argentine names

Footnotes

- The United Kingdom was called the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland until the Royal and Parliamentary Titles Act 1927, following Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1922. The current name United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland has been in use since 1927.

References

- "John Strong | English statesman". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Calvert, Peter (July 1983). "Sovereignty and the Falklands crisis". International Affairs. Chatham House RIIA. 59 (3): 406. doi:10.2307/2618794. ISSN 0020-5850. JSTOR 2618794. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

-

de Bougainville, Louis (4 October 1766). "Instrumento que otorgó M. Bougainville para la entrega de las Malvinas" [Document from M. Bougainville for delivery of the Falklands] (PDF) (in Spanish). Dirección General de Cultura y Educación, Buenos Aires Provincia, Argentina. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

the expenses incurred by the St. Malo Company in equipments for founding their intrusive establishments in the Malvina Islands

- Lewis, Jason; Inglis, Alison. "Part 2 – Fort St. Louis and Port Egmont". A brief history of the Falkland Islands. falklands.info . Archived from the original on 6 October 2007. Retrieved 19 July 2007.

- Laver, Roberto C. (February 2001). The Falklands/Malvinas Case Breaking The Deadlock in the Anglo-Argentine Sovereignty Dispute, Developments in International Law, V. 40 (Book 40). Springer. ISBN 978-9041115348.

- Samuel Edward Dawson (1899). The Lines of demarcation of Pope Alexander VI and the Treaty of Tordesillas A.D. 1493 and 1494. Hope & Sons. p. 543.

- Harris, Chris (27 May 2002). "Declarations signed by Masserano and Rochford January 22nd 1771". The history of the Falkland Islands. Archived from the original on 16 June 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- Mary Cawkell (1983). The Falkland Story, 1592–1982. Anthony Nelson Limited. ISBN 978-0-904614-08-4.

- Goebel, Julius (1927). The Struggle for the Falkland Islands: A Study in Legal and Diplomatic History. Yale University Press. p. 483.

- Hoffman, Fritz L.; Hoffman, Olga Mingo (1984). Sovereignty in Dispute: The Falklands/Malvinas, 1493–1982. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. p. 65. ISBN 0-86531-605-8.

- Lewis, Jason; Inglis, Alison. "Part 1 – The Discovery of the Falkland Islands". A brief history of the Falkland Islands. falklands.info . Archived from the original on 6 October 2007. Retrieved 19 July 2007.

- Mary Cawkell (2001). The History of the Falkland Islands. Nelson. ISBN 978-0-904614-55-8.

- Daniel K. Gibran (2008). The Falklands War: Britain versus the past in the South Atlantic. McFarland & Co Inc Publishing. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-7864-3736-8.

- Lawrence Freedman (10 September 2012). Official History of the Falklands. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-77589-6. Retrieved 24 April 2013. At a time of growing unrest in its American colonies, the Falklands appeared expensive and of marginal strategic value and so Saunders Island was left voluntarily in 1774 as Britain concentrated on North America.

- Mary Cawkell (2001). The History of the Falkland Islands. Anthony Nelson. ISBN 978-0-904614-55-8., p. 48.

- "February 1833: Parallel truths in parallel universes — can that be the only explanation? - BuenosAiresHerald.com". Buenosairesherald.com. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- Mary Cawkell (2001). The History of the Falkland Islands. Anthony Nelson. ISBN 978-0-904614-55-8., p.51

- Ricardo Rodolfo Caillet-Bois (1952). Las Islas Malvinas: una tierra argentina. Ediciones Peuser., p. 209

- Peterson, Harold (1964). Argentina and the United States 1810–1960. New York: University Publishers Inc. ISBN 978-0-87395-010-7., p.106

- Graham-Yooll, Andrew (2002). Imperial Skirmishes: War and Gunboat Diplomacy in Latin America. Oxford, England: Signal Books Limited. ISBN 978-1-902669-21-2., p.50

- Graham-Yooll, Andrew (2002). Imperial Skirmishes: War and Gunboat Diplomacy in Latin America. Oxford, England: Signal Books Limited. ISBN 978-1-902669-21-2., p.51

- Harold F. PETERSON (1964). Argentina and the United States: 1810–1960. SUNY Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-87395-010-7. "Denying that Argentine officials had the right of seizure or the right to restrain American citizens from use of the fisheries, he said he regarded Anchorema's note as an avowal of Vernet's captures. He protested against the decree of June 10, 1829."

- Laurio Hedelvio Destéfani (1982). The Malvinas, the South Georgias, and the South Sandwich Islands, the conflict with Britain. Edipress. ISBN 978-950-01-6904-2. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- Gustafson, Lowell S. (7 April 1988). The Sovereignty Dispute Over the Falkland (Malvinas) Islands. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-536472-9. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- Gurney, Alan (1 June 2008). "Matthew Brisbane". In Tatham, David (ed.). The Dictionary of Falklands Biography (Including South Georgia): From Discovery Up to 1981. D. Tatham. pp. 115–119. ISBN 978-0-9558985-0-1. Retrieved 15 August 2011.)

- FitzRoy, R. 1839. Narrative of the surveying voyages of His Majesty's Ships Adventure and Beagle. Vol. II.

- Islas del Atlántico Sur, Islas Malvinas, Historia, Ocupación británica: Port Stanley (Puerto Argentino). Cpel.uba.ar. Retrieved on 20 November 2011. Archived 15 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "The Official Position of the Argentine Ministry of Foreign Affairs on the Falklands (Malvinas) Question and on the Historical Background". 16 December 2018. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- Speech by Dr. José María Ruda (Argentina) to the UN Special Committee on the Situation with regard to the Implementation of the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, 9 September 1964 cited in Manuel Pedro Peña; Juan Ángel Peña (20 November 2017). Falklands or Malvinas: Myths & facts. Pentian. pp. Appendix II. ISBN 978-1-5243-0127-9.

- According to the historical claim of the Argentine Republic, we emphasize that the principle of self-determination is not applicable to the issue of the Falkland Islands. Precisely, with regard to this principle, the specificity of the Malvinas question lies in the fact that the United Kingdom occupied the Islands by force in 1833, expelled their original population and did not allow their return, violating Argentine territorial integrity. Thus, the possibility of applying the principle of self-determination is ruled out, since its exercise by the inhabitants of the islands would cause the breakdown of national unity and territorial integrity of Argentina. The Senate and Chamber of Deputies (8 March 2006). "AMENDMENT OF ARTICLE 1 OF LAW No. 23,775 PROVINCIALIZATION OF THE TERRITORY OF TIERRA DEL FUEGO, ANTARTIDA AND ISLANDS OF THE SOUTH ATLANTIC". Chamber of Deputies of the Nation (Argentina) (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- Ernesto J. Fitte (1966). La agresión norteamericana a las Islas Malvinas: Crónica documental. Emecé, Editores. pp. 372–373.

- Mario Tesler (1971). El gaucho Antonio Rivero: la mentira en la historiografía académica. A. Peña Lillo. pp. 235–237.

- Lewis, Jason; Inglis, Alison. "Falkland Islands Newsletter, No.14, May 1983". The Long View of the Falklands Situation. falklands.info. Archived from the original on 6 October 2007. Retrieved 19 July 2007.

- Warnick, Shannon (2008). The reluctant colonization of the Falkland Islands, 1833–1851 : a study of British Imperialism in the SouthwestAtlantic" (Masters). University of Richmond.

- Canning, George (15 December 1823). "Foreign Office December 15th 1823". Official document. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

The King my Master ... with a view to such measures as may eventually lead to the establishment of friendly Relations with the Government of Buenos Ayres, has determined to nominate and appoint Woodbine Parish Esq. to be His Majesty's Consul General in the State of Buenos Ayres. ... (Signed:) George Canning

- Canning, George (2 February 1825). "Treaty of Amity, Commerce and Navigation". Official document. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

... the Territories of The United Provinces of Rio de La Plata; for the Maintenance of good Understanding between His said Britannick Majesty and the said United Provinces ... should be regularly acknowledged and confirmed by the Signature of a Treaty of Amity, Commerce and Navigation. ... Done at Buenos Ayres, the second day of February, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and twenty-five. (Signed:) Woodbine Parish, H.M. Consul-General, Manl. J. Garcia.

- Mikulas Fabry, Recognizing states international society and the establishment of new states since 1776, pp. 68, 77 n. 88, which cites George Canning's letter to Woodbine Parish of Boxing Day, 1824; the British did not even decide their position on the status of Uruguay, then disputed with the Empire of Brazil, until 1825; George P. Mills, Argentina, p. 203; see also the website of the Argentine Foreign Ministry Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Other sources count effective recognition from the Treaty of Amity and Commerce, concluded 2 February 1825, in Buenos Aires.

- Report dated 30 April 1822 by Portuguese Auditor General of Marine, Manuel José de Figueredo; translated version reprinted in William R. Manning: Diplomatic Correspondence of the United States, Inter-American Affairs 1831–1860, Vol I, Argentina, Washington DC 1932, fn. 1, pp. 169–71.

- Weddell, James (1827). A Voyage Towards the South Pole. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green.

- da Fonseca Figueira; José Antonio (1985). David Jewett; una biografía para la historia de las Malvinas (in Spanish). Sudamericana-Planeta. pp. 105–15. ISBN 950-37-0168-6.

- "False Falklands History at the United Nations" (PDF). May 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- Caillet-Bois, Ricardo R. (1952). Las Islas Malvinas (2nd ed.). Ediciones Peuser. pp. 195–99.

- Lewis, Jason; Inglis, Alison. "Part 3 – Louis Vernet: The Great Entrepreneur". A brief history of the Falkland Islands. falklands.info. Archived from the original on 1 April 2010. Retrieved 19 July 2007.

- s:Report by Silas Duncan Commander U.S.S. Lexington sent to Navy Secretary Levi Woodbury. Report by Silas Duncan, Commander USS Lexington sent to Levi Woodbury, the US Navy Secretary on 2 February 1832.

- Monroe, Alexander G. (27 July 1997). "Commander Silas Duncan and the Falkland Island Affair". USS Duncan DDR 874 Crew & Reunion Association. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- "Williams v. Suffolk Insurance Company :: 38 U.S. 415 (1839) :: Justia U.S. Supreme Court Center". Justia Law.

- "Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores, Argentina's Position on Different Aspects of the Question of the Malvinas Islands". Mrecic.gov.ar. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- Laver, Roberto C (2001). The Falklands/Malvinas case: breaking the deadlock in the Anglo-Argentine sovereignty dispute. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 88–89. ISBN 9789041115348.

- Bluth, Christoph (March 1987). "The British Resort to Force in the Falklands/Malvinas Conflict 1982". Journal of Peace Research. 24 (1): 5–20. doi:10.1177/002234338702400102. S2CID 145424339.

- The Falkland Islands, A history of the 1982 conflict, Preface to a conflict. Royal Air Force. raf.mod.uk

- "The Issue is the Law". The Times (London). 27 April 1982. p. 13.

- "UN 2065 (XX). Question of the Falkland Islands (Malvinas)". Resolutions adopted on the reports of the Fourth Committee. United Nations. 16 December 1965.

- "1971 AGREEMENT ON COMMUNICATIONS BETWEEN THE FALKLAND ISLANDS AND ARGENTINA" (PDF). 16 December 2018. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- H.Cámara de Diputados de la Nación Archived 29 November 2012 at Archive.today. Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires. 25 August 2006

- Grumman HU-16B Albatross. Asociación Tripulantes de Transporte Aéreo. Argentine Air Force Archived 13 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Fokker F-27 Troopship/Friendship. Asociación Tripulantes de Transporte Aéreo. Argentine Air Force. Archived 22 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- La Fuerza Aérea en Malvinas desde 1971 hasta 1982 Archived 14 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Argentine Air Force.

- Norton-Taylor, Richards; Evans, Rob (28 June 2005). "UK held secret talks to cede sovereignty: Minister met junta envoy in Switzerland, official war history reveals". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- Bound, Graham (2002). Falkland Islanders at War. Pen & Swords Ltd. ISBN 1-84415-429-7.

- "Secret Falklands fleet revealed", BBC News, 1 June 2005

- "UN Resolution 502 (1982)" (PDF). United Nations Security Council 2350th meeting. 3 April 1982. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2014.

- "U.N. Resolution on Falkland War". The New York Times. 5 June 1982. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- Sanctions during Falkland Islands Conflict. Columbia International Affairs Online.

- "Falkland Islands Patrol Vessel". Royal Navy. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Goni, Uki (1 March 2012). "Argentine president calls for direct flights from Falklands to Buenos Aires". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- "Country Profile: Falkland Islands (British Overseas Territory)". Fco.gov.uk. 5 November 2009. Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "UN A/RES/37/9. Question of the Falkland Islands (Malvinas)". United Nations General Assembly. 4 November 1982. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "UK current arms embargo". United Kingdom Government. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- "Britain Eases Post-Falklands Arms Embargo Against Argentina". The New York Times. 18 December 1998. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- "Blair y Kirchner adelantaron diálogo". BBC World Service (in Spanish). 14 July 2003. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- McDermott, Jeremy (30 June 2006). "Argentina renews campaign over Falklands claim". The Telegraph.

- Bourne, Brendan (28 March 2009). "Gordon Brown rejects Argentina's claim to the Falklands". The Times (London).

- Piette, Candace (22 April 2009). "Argentina claims vast ocean area". BBC News.

- https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2009/apr/24/falklands-britain-argentina-dispute-seabed

- "Oil drilling begins in the Falkland Islands". Channel 4 News. 21 February 2010.

- "Argentina toughens shipping rules in Falklands oil row". BBC. 17 February 2010.

- "Press conference with Chief Cabinet Aníbal Fernández (Conferencia de Prensa del Jefe de Gabinete Aníbal Fernández)" (Press release). 16 February 2010. Archived from the original on 26 March 2010.

- "Drilling for oil begins off the Falkland Islands". BBC News. 22 February 2010. Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- "Argentina and the Falklands: Rocking the boat". The Economist. 31 December 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- Borger, J. (1 February 2013). "UK 'disappointed' as Argentina turns down talks over Falklands". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- "Falkland Islands: respect overwhelming 'yes' vote, Cameron tells Argentina". The Guardian. 12 March 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Falklands referendum: Voters choose to remain UK territory". BBC UK. 12 March 2013.

- "Malvinas: la ONU hará más gestiones para abrir el diálogo". Lanacion.com.ar. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- Hasani, Enver. "Uti Possidetis Juris: From Rome To Kosovo". Fletcher Forum of World Affairs.

- Rizzo Romano; Alfredo H. (1987). "El estoppel y la problemática jurídicopolítica de las Islas Malvinas". La Ley. A (847). Archived from the original on 5 September 2011.

El Reino Unido jamás protestó o efectuó reserva alguna ante la larga, pacífica, efectiva y pública posesión hispana sobre las Islas Malvinas y sus dependencias del Atlántico Sur, durante casi 60 años; plazo mucho mayor que el exigido por tribunales internacionales para adquirir por prescripción. English: The United Kingdom never protested or expressed reservations during the long, pacific, effective and public Spanish possession over the Falkland Islands and its dependencies, during almost 60 years; a period much longer than the required by international tribunals for acquisition by prescription to occur.

- Escude, Carlos; Cisneros, Andres (2000). Historia de las Relaciones Exteriores Argentinas (in Spanish). GEL/Nuevohacer. ISBN 950-694-546-2. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

De este modo, a lo largo de 47 años (1764-1811) España ocupó ininterrumpidamente las islas perfeccionando sus derechos. English: In this way, during 47 years (1764-1811) Spain uninterruptedly occupied the islands, perfecting its rights.

- Gustafson, Lowell S. (1988). Sovereignty Dispute over the Falkland (Malvinas) Islands. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504184-4.

- Gustafson, pp. 21–25. "But at the very least, Jewitt had publicly claimed possession in the name of Argentina, whose government could later confirm or deny his claim. The government would confirm Jewitt's claim." (p. 22)

- Reisman, W. Michael (1983). "The Struggle for The Falklands". The Yale Law Journal. Yale Law School. 93 (2): 299. doi:10.2307/796308. JSTOR 796308.

- Hope (1983). "Sovereignty and Decolonization of the Makvinas (Falkland) Islands". Boston College International & Comparative Law Review. Boston College Law School. 6 (2): 413–416.

- Argentine diplomatic protest for the occupation of the Malvinas in 1833

- Gustafson 1998, p. 34.

- Argentina’s Position on Different Aspects of the Question of the Malvinas Islands Archived 9 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- Brilmayer, Lea (1991). "Secession and Self-Determination: A Territorial Interpretation". Yale Journal of International Law. 16: 177–202.

- Although a signatory to the 1958 convention, Argentina never ratified the convention."Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 11 March 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Archived 26 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine Convention on the Continental Shelf, Geneva, 29 April 1958. UN.org. The 1958 Convention was superseded by 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, ratified by Argentina in 1995. Rupert Cornwall Could Oil Exploration of the Falklands Lead to a Renewal of Hostilities?. The Independent, 23 February 2010; cited by the Global Policy Forum

- Luna, Félix (2003). Los conflictos armados. Buenos Aires: La Nación. pp. 12–17. ISBN 950-49-1123-4.

- E.O.S Scholefield British Columbia from Earliest Times to Present Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. p. 666

- "The Argentine Seizure of the Malvinas [Falkland] Islands: History and Diplomacy". May 2008. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- Todini, Bruno (2007). Falkland Islands, History, War and Economics. Chapter 2: Beginning of the disputes over the Falkland islands sovereignty among Spanish, British and French. pp. 252–53. ISBN 978-84-690-6590-7. Archived from the original on 29 November 2009. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

- "Constitución Nacional" (in Spanish). 22 August 1994. Archived from the original on 17 June 2004. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- "Constitution of the Argentine Nation". 22 August 1994. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- Franks, Lord (1992). Falkland Islands Review: Report of a Committee of Privy Counsellors. Chmn.Lord Franks. Pimlico Books. ISBN 9780712698405.

- "Falklands: "No return to the 80s", tacit UK/Argentine agreement". MercoPress South Atlantic News Agency. 29 March 2010. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

... as a country and as democrats we believe in self determination, and if the people of the Islands want to remain British, that is their choice and we will always support them", said [Foreign Office minister Chris] Bryant who insisted that "we have no doubts as to whom the Falklands belong". Besides in the European Union Lisbon Treaty "it is clearly spelled out that the Falklands belong to Britain".

- "Falkland Islanders must be masters of their own fate" (Press release). British Foreign & Commonwealth Office. 21 January 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- UK says Falklands’ self determination is a universal right enshrined in UN charter MercoPress, 25 January 2013

- "Travel Advice: Falkland Islands (British Overseas Territory)". British Foreign & Commonwealth Office (FCO). March 2012. Archived from the original on 25 September 2012.

- "Falklands referendum: Voters choose to remain UK territory". BBC News. 12 March 2013.

- "Falkland Islands: respect overwhelming 'yes' vote, Cameron tells Argentina". The Guardian. 12 March 2013.

- "Falkland Islanders' right to self-determination - GOV.UK". www.gov.uk.

- "COFFEY: Falklands are British, not Argentine". Washington Times. March 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- "UK Ambassador responds to "manifestly absurd" Argentine claims (Transcript of a Press Conference held by Ambassador Sir Mark Lyall Grant)" (Press release). United Kingdom Mission to the United Nations. 10 February 2012. Archived from the original on 17 February 2013. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- "Chapter 1 of the Falkland Islands Constitution". Office of Public Sector Information. 5 November 2008. Retrieved 26 February 2010.

- Miller, Vaughne. "Argentina and the Falkland Islands" (PDF). House of Commons Library. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- "Q&A: Argentina's diplomatic offensive on Falklands". BBC News. 14 June 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- "英屬福克蘭群島 Falkland Islands" (in Chinese). Bureau of Consular Affairs, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of China (Taiwan). Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- "United Nations Documents on the Falklands-Malvinas Conflict". South Atlantic Council. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- "U.S. Position on the Falkland (Malvinas) Islands". US Department of State. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- The Commonwealth Yearbook 2012 (PDF). Commonwealth Secretariat. 2012. ISBN 978-0-9563060-9-8.

- "OAS backs Argentina Falklands claim". The Express. 6 June 2012.

- "OAS declaration in support of Malvinas UK/Argentina talks; Canada disagreed". Mercopress. 17 June 2015.

Sources

- Escudé, Carlos; Cisneros, Andrés, eds. (2000), Historia de las Relaciones Exteriores Argentinas (in Spanish), Buenos Aires: GEL/Nuevohacer under auspices of Argentine Council for International Relations (CARI), ISBN 950-694-546-2, archived from the original on 28 May 2007

- Chenette, Lt Cdr Richard D, USN (1987), The Argentine Seizure of the Malvinas (Falkland) Islands: History and Diplomacy, US Marine Corps Staff College Research Paper

- Destéfani, Laurio H. (1982), The Malvinas, the South Georgias and the South Sandwich Islands, the conflict with Britain, Buenos Aires: Edipress, ISBN 950-01-6904-5

- Fox, Robert (1992), Eyewitness Falklands, Mandarin, ISBN 0-7493-1215-7

- Greig, D.W (1983), "Sovereignty and the Falkland Islands Crisis" (PDF), Australian Year Book of International Law, 8, pp. 20–70

- Hastings, Max; Jenkins, Simon (1997), The Battle for the Falklands, Pan, ISBN 0-330-35284-9

- L.L. Ivanov et al. The Future of the Falkland Islands and Its People. Sofia: Manfred Wörner Foundation, 2003. Printed in Bulgaria by Double T Publishers. 96 pp. ISBN 954-91503-1-3

Further reading

- Raimondo, F. (2012). "The Sovereignty Dispute over the Falklands/Malvinas: What Role for the UN?". Neth. Int. Law Rev. 59 (3): 399–423. doi:10.1017/S0165070X12000277. S2CID 145587892.