Flag of Germany

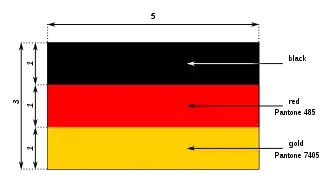

The flag of Germany (German: Flagge Deutschlands) is a tricolour consisting of three equal horizontal bands displaying the national colours of Germany: black, red, and gold (German: Schwarz-Rot-Gold).[1] The flag was first sighted in 1848 in the German Confederation; with it being officially adopted as the national flag of the Weimar Republic from 1919–1933, and again being in use since its reintroduction in West Germany back in 1949.

| |

| Use | Civil and state flag, civil ensign |

|---|---|

| Proportion | 3:5 |

| Adopted | 23 May 1949 |

| Design | A horizontal tricolour of black, red, and gold |

.svg.png.webp) Variant flag of Federal Republic of Germany | |

| Use | State flag and ensign, war flag |

| Proportion | 3:5 |

| Adopted | 7 June 1950 |

| Design | The civil flag with the coat of arms at the center. |

Variant flag of Federal Republic of Germany | |

| Name | Dienstflagge der Seestreitkräfte der Bundeswehr |

| Use | Naval ensign |

| Proportion | 3:5 |

| Adopted | 25 May 1956 |

| Design | A swallowtail of the civil flag with the coat of arms at the center. |

.svg.png.webp)

Since the mid-19th century, Germany has two competing traditions of national colours, black-red-gold and black-white-red. Black-red-gold were the colours of the 1848 Revolutions, the Weimar Republic of 1919–1933 and the Federal Republic (since 1949). They were also adopted by the German Democratic Republic (1949–1990) (albeit defaced with its "socialist" coat of arms from 1959 until reunification in 1990).

The colours black-white-red appeared for the first time in 1867, in the constitution of the North German Confederation. This nation state for Prussia and other north and central German states was expanded to the south German states in 1870–71, under the name German Empire. It kept these colours until the revolution of 1918–19. Thereafter, black-white-red became a symbol of the political right. The national socialists (Nazi Party) re-established these colours along with the party's own swastika flag in 1933. After World War II, black-white-red was still used by some conservative groups or by groups of the far right – as it is not forbidden, unlike proper national socialist symbols.

Black-red-gold is the official flag of the Federal Republic of Germany. As an official symbol of the constitutional order, it is protected against defamation. According to §90 of the German penal code, the consequences are a fine or imprisonment up to five years.

Origins

The German association with the colours black, red, and gold surfaced in the radical 1840s, when the black-red-gold flag was used to symbolize the movement against the Conservative European Order that was established after Napoleon's defeat.

There are many theories in circulation regarding the origins of the colour scheme used in the 1848 flag. It has been proposed that the colours were those of the Jena Students' League (Jenaer Burschenschaft), one of the radically minded Burschenschaften banned by Metternich in the Carlsbad Decrees; the colours are mentioned in their canonical order in the seventh verse of August Daniel von Binzer's student song Zur Auflösung der Jenaer Burschenschaft ("On the Dissolution of the Jena Students' League") quoted by Johannes Brahms in his Academic Festival Overture.[2] Another claim goes back to the uniforms (mainly black with red facings and gold buttons) of the Lützow Free Corps, comprising mostly university students and formed during the struggle against the occupying forces of Napoleon. Whatever the true explanation, these colours soon came to be regarded as the national colours of Germany during this brief period, and especially after their reintroduction during the Weimar period, they have become synonymous with liberalism in general.[3] The colours also appear in the medieval Reichsadler.

Flag variants

Civil flag

The German national flag or Bundesflagge (English: Federal flag), containing only the black-red-gold tricolour, was introduced as part of the (West) German constitution in 1949.[4] Following the creation of separate government and military flags in later years, the plain tricolour is now used as the German civil flag and civil ensign. This flag is also used by non-federal authorities to show their connection to the federal government, e.g. the authorities of the German states use the German national flag together with their own flag.

Government flag

The government flag of Germany is officially known as the Dienstflagge der Bundesbehörden (state flag of the federal authorities) or Bundesdienstflagge for short. Introduced in 1950, the government flag is the civil flag defaced with the Bundesschild ("Federal Shield"), which overlaps with up to one fifth of the black and gold bands.[5] The Bundesschild is a variant of the coat of arms of Germany, whose main differences are the illustration of the eagle and the shape of the shield: the Bundesschild is rounded at the base, whereas the standard coat of arms is pointed.

The government flag may only be used by federal government authorities and its use by others is an offence, punishable with a fine.[6] However, public use of flags similar to the Bundesdienstflagge (e.g. using the actual coat of arms instead of the Bundesschild) is tolerated, and such flags are sometimes seen at international sporting events.

Vertical flags

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

In addition to the normal horizontal format, many public buildings in Germany use vertical flags. Most town halls fly their town flag together with the national flag in this way; many town flags in Germany exist only in vertical form. The proportions of these vertical flags are not specified. In 1996, a layout for the vertical version of the government flag was established, that coincidentally matched the pattern of the "conventional" black-red-gold flag of the Principality of Reuss-Gera (Fürstentum Reuß-Gera) from 1806–1918: the Bundesschild is displayed in the centre of the flag, overlapping with up to one fifth of the black and gold bands.[7] When hung like a banner or draped, the black band should be on the left, as illustrated. When flown from a vertical flagpole, the black band must face the staff.[8]

Military flags

Since the German armed forces (Bundeswehr) are a federal authority, the Bundesdienstflagge is also used as the German war flag on land. In 1956, the Dienstflagge der Seestreitkräfte der Bundeswehr (Flag of the German Navy) was introduced: the government flag ending in swallowtail. This naval flag is also used as a navy jack.

Design

Article 22 of the German constitution, the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, states:

The federal flag shall be black, red and gold.[4]

Following specifications set by the West German government in 1950, the flag displays three bars of equal width and has a width–length ratio of 3:5;[5] the tricolour used during the Weimar Republic had a ratio of 2:3.[10]

At the time of the adoption of the flag there were no exact colour specifications other than "Black-Red-Gold".[11][12] However on 2 June 1999, the federal cabinet introduced a corporate design for the German government which defined the specifications of the official colours as:[13][14]

| Colour scheme | Black | Red | Gold | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAL | 9005 Jet black |

3020 Traffic red |

1021 Rapeseed yellow | |||

| HKS | 0, 0, 0 | 5.0PB 3.0/12 | 6.0R 4.5/14 | |||

| CMYK | 0.0.0.100 | 0.100.100.0 | 0.12.100.5 | |||

| Pantone (approximation) | Black | 485 | 7405[lower-alpha 1] | |||

| Web colour | #000000 | #FF0000 | #FFCC00[lower-alpha 2] | |||

| Decimal RGB | 0,0,0 | 255,0,0 | 255,204,0 | |||

- The value given here is an alternative to the following more-complicated combination: Yellow (765 g), Red 032 (26 g), Black (11 g), Transp. White (198 g)

- Recommended RGB values for online use.

Colour

Vexillology rarely distinguishes between gold and yellow; in heraldry, they are both Or. For the German flag, such a distinction is made: the colour used in the flag is called gold, not yellow.

When the black–red–gold tricolour was adopted by the Weimar Republic as its flag, it was attacked by conservatives, monarchists, and the far right, who referred to the colours with spiteful nicknames such as Schwarz–Rot–Gelb (black–red–yellow) or even Schwarz–Rot–Senf (black–red–mustard).[15] When the Nazis came to power in 1933, the black–white–red colours of pre-1918 Imperial Germany were swiftly reintroduced, and their propaganda machine continued to discredit the Schwarz–Rot–Gold, using the same derogatory terms as previously used by the monarchists.[16]

On 16 November 1959, the Federal Court of Justice (Bundesgerichtshof) stated that the usage of "black–red–yellow" and the like had "through years of Nazi agitation, attained the significance of a malicious slander against the democratic symbols of the state" and was now an offence.[16] As summarised by heraldist Arnold Rabbow in 1968, "the German colours are black–red–yellow but they are called black–red–gold."[17]

Flag days

Following federal decree on 22 March 2005, the flag must be flown from public buildings on the following dates. Only 1 May and 3 October are public holidays.

| Date | Name | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| 27 January | Commemoration Day for the Victims of National Socialism Tag des Gedenkens an die Opfer des Nationalsozialismus |

Anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz concentration camp (1945), observed by the United Nations as International Holocaust Remembrance Day (half-staff) |

| 1 May | Day of Labour Tag der Arbeit |

Established for German labour unions to demonstrate for the promotion of workers' welfare. |

| 9 May | Europe Day Europatag |

Anniversary of the Schuman Declaration, leading to the European Union (1950) |

| 23 May | Constitution Day Grundgesetztag |

Anniversary of the German Basic Law (1949) |

| 17 June | Anniversary of the 17th of June 1953 Jahrestag des 17. Juni 1953 |

Anniversary of the Uprising of 1953 in East Berlin and East Germany |

| 20 July | Anniversary of the 20th of July 1944 Jahrestag des 20. Juli 1944 |

Anniversary of the July 20 plot, the failed assassination attempt on Adolf Hitler by Claus von Stauffenberg (1944) |

| 3 October | Day of German Unity Tag der Deutschen Einheit |

Anniversary of German reunification (1990) |

| The 2nd Sunday before Advent | People's Mourning Day Volkstrauertag |

In memory of all killed during wartime (half-staff) |

Source: Federal Government of Germany[18] | ||

Election days for the Bundestag and the European Parliament are also flag days in some states, in addition to other state-specific flag days. The public display of flags to mark other events, such as the election of the president or the death of a prominent politician (whereupon flags would be at half-staff), can be declared at the discretion of the Federal Ministry of the Interior.[18] When flags are required to be flown at half-staff, vertical flags are not lowered. A black mourning ribbon is instead attached, either atop the staff (if hung from a pole) or to each end of the flag's supporting cross-beams (if flown like a banner).[19]

History

Medieval period

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

The Holy Roman Empire (800/962 – 1806, known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512) did not have a national flag, but black and gold were used as colours of the Holy Roman Emperor and featured in the imperial banner: a black eagle on a golden background. After the late 13th or early 14th century, the claws and beak of the eagle were coloured red. From the early 15th century, a double-headed eagle was used.[20]

Principality of Reuss-Greiz

.svg.png.webp)

When Heinrich XI, Prince Reuss of Greiz was appointed by Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor to rule the then-new Principality of Reuss-Greiz on 12 May 1778, the flag adopted by the Fürstentum Reuß-Greiz was the first-ever appearance of the black-red-gold tricolour in its modern arrangement in any sovereign state within what today comprises Germany – the Reuss elder line that ruled the principality used a flag whose proportions were close to a "nearly square"-shape 4:5 hoist/fly ratio, instead of the modern German flag's 3:5 figure.

In 1804, Napoleon Bonaparte declared the First French Empire. In response to this, Holy Roman Emperor Francis II of the Habsburg dynasty declared his personal domain to be the Austrian Empire and became Francis I of Austria. Taking the colours of the banner of the Holy Roman Emperor, the flag of the Austrian Empire was black and gold. Francis II was the last Holy Roman Emperor, with Napoleon forcing the empire's dissolution in 1806. After this point, these colours continued to be used as the flag of Austria until 1918.

The colours red and white were also significant during this period. When the Holy Roman Empire took part in the Crusades, a war flag was flown alongside the black-gold imperial banner. This flag, known as the "Saint George Flag", was a white cross on a red background: the reverse of the St George's Cross used as the flag of England, and similar to the flag of Denmark.[20] Red and white were also colours of the Hanseatic League (13th–17th century). Hanseatic trading ships were identifiable by their red-white pennants, and most Hanseatic cities adopted red and white as their city colours (see Hanseatic flags). Red and white still feature as the colours of many former Hanseatic cities such as Hamburg or Bremen.

Napoleonic Wars

With the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, many of its dukes and princes joined the Confederation of the Rhine, a confederation of Napoleonic client states. These states preferred to use their own flags. The confederation had no flag of its own; instead it used the blue-white-red flag of France and the Imperial Standard of its protector, Napoleon.[21]

During the Napoleonic Wars, the German struggle against the occupying French forces was significantly symbolised by the colours of black, red, and gold, which became popular after their use in the uniforms of the Lützow Free Corps, a volunteer unit of the Prussian Army. This unit had uniforms in black with red facings and gold buttons. The colour choice had pragmatic origins, even though black-red-gold were the former colours used by the Holy Roman Empire.[22] At the time, the colours represented:

Out of the blackness (black) of servitude through bloody (red) battles to the golden (gold) light of freedom.[23]

Members of the corps were required to supply their own clothing: in order to present a uniform appearance it was easiest to dye all clothes black. Gold-coloured buttons were widely available, and pennons used by the lancers in the unit were red and black. As the members of this unit came from all over Germany and included a modest but well known number of university students and academics, the Lützow Free Corps and their colours gained considerable exposure among the German people.[22]

German Confederation

The 1815–16 Congress of Vienna led to the creation of the German Confederation, a loose union of all remaining German states after the Napoleonic Wars. The Confederation was created as a replacement for the now-extinct Holy Roman Empire, with Francis I of Austria—the last Holy Roman Emperor—as its president. The confederation did not have a flag of its own, although the black-red-gold tricolour is sometimes mistakenly attributed to it.[24]

Upon returning from the war, veterans of the Lützow Free Corps founded the Urburschenschaft fraternity in Jena in June 1815. The Jena Urburschenschaft eventually adopted a flag with three equal horizontal bands of red, black, and red, with gold trim and a golden oak branch across the black band, following the colours of the uniforms of the Free Corps.[22] The famous gymnast and student union (Burschenschaften) founder Friedrich Ludwig Jahn proposed a black-red-gold banner for the Burschen. Some members interpreted the colours as a rebirth of the Imperial black-yellow colours embellished with the red of liberty or the blood of war. More radical students exclaimed that the colours stood for the black night of slavery, the bloody struggle for liberty, and the golden dawn of freedom.[25] In a memoir, Anton Probsthan of Mecklenburg, who served in the Lützow Free Corps, claimed his relative Fraulein Nitschke of Jena presented the Burschenschaft with a flag at the time of its foundation, and for this purpose chose the black-red-and-gold colours of the defunct secret society Vandalia.[26]

Since the students who served in the Lützow Free Corps came from various German states, the idea of a unified German state began to gain momentum within the Urburschenschaft and similar Burschenschaft that were subsequently formed throughout the Confederation. On 18 October 1817, the fourth anniversary of the Battle of Leipzig, hundreds of fraternity members and academics from across the Confederation states met in Wartburg in Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach (in modern Thuringia), calling for a free and unified German nation.

The gold-red-black flag of the Jena Urburschenschaft featured prominently at this Wartburg festival. Therefore, the colours black, red, and gold eventually became symbolic of this desire for a unified German state. The Ministerial Council of the German Confederation, in its determination to maintain the status quo,[27] enacted the Carlsbad Decrees of 1819 that banned all student organisations, officially putting an end to the Burschenschaften.

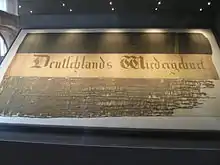

In May 1832, around 30,000 people demonstrated at the Hambach Festival for freedom, unity, and civil rights. The colours black, red, and gold had become a well established symbol for the liberal, democratic and republican movement within the German states since the Wartburg Festival, and flags in these colours were flown en masse at the Hambach Festival. While contemporary illustrations showed prominent use of a gold-red-black tricolour (an upside-down version of the modern German flag), surviving flags from the event were in black-red-gold. Such an example is the Ur-Fahne, the flag flown from Hambach Castle during the festival: a black-red-gold tricolour where the red band contains the inscription Deutschlands Wiedergeburt (Germany's rebirth). This flag is now on permanent display at the castle.[28]

Revolution and the Frankfurt Parliament

.svg.png.webp)

In the Springtime of the Peoples during the Revolutions of 1848, revolutionaries took to the streets, many flying the tricolour. The Confederation's Bundestag, alarmed by the events, hasted to adopt the tricolour (March 9th, 1848). Liberals took power and made the Bundestag call for general elections for a German parliament, the national assembly. This Frankfurt Parliament declared the black-red-gold as the official colours of Germany and passed a law stating its civil ensign was the black-red-yellow tricolour.[29] Also, a naval war ensign used these colours.

In May 1849, the larger states actively fought the revolution and the Frankfurt parliament. In late 1850, the German Confederation was definitely restored under Austrian-Prussian leadership. The tricolour remained official but was no longer used before 1863 at a conference of the German governments. Afterwards, the most pressing issue was whether or not to include Austria in any future German nation, as Austria's status as a multi-ethnic empire complicated the dream of a united Greater Germany—the grossdeutsch solution. Alternatively, there was the kleindeutsch (Lesser German) solution for a Germany that encompassed only German lands and excluded Austria. The Prussian–Austrian duality within the Confederation eventually led to the Austro-Prussian War in 1866. During the war, the southern states allied with Austria adopted the black-red-gold tricolour as their flag, and the 8th German Army Corps also wore black-red-gold armbands.[24] The Kingdom of Prussia and its predominately north German allies defeated Austria and made way for the realisation of the Lesser German solution a few years later.

North German Confederation and the German Empire (1867–1918)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

Following the dissolution of the German Confederation, Prussia formed its unofficial successor, the North German Confederation, in 1866 with the signing of the Confederation Treaty in August 1866 and then the ratification of the Constitution of 1867. This national state consisted of Prussia, the largest member state, and 21 other north German states.

The question regarding what flag should be adopted by the new confederation was first raised by the shipping sector and its desire to have an internationally recognisable identity. Virtually all international shipping that belonged to the confederation originated from either Prussia or the three Hanseatic city-states of Bremen, Hamburg, and Lübeck. Based on this, Adolf Soetbeer, secretary of the Hamburg Chamber of Commerce, suggested in the Bremer Handelsblatt on 22 September 1866 that any planned flag should combine the colours of Prussia (black and white) with the Hanseatic colours (red and white). In the following year, the constitution of the North German Confederation was enacted, where a horizontal black-white-red tricolour was declared to be both the civil and war ensign.[30]

King Wilhelm I of Prussia was satisfied with the colour choice: the red and white were also taken to represent the Margraviate of Brandenburg, the Imperial elector state that was a predecessor of the Kingdom of Prussia.[22] The absence of gold from the flag also made it clear that this German state did not include the "black and gold" monarchy of Austria. In the Franco-Prussian War, the remaining southern German states allied with the North German Confederation, leading to the unification of Germany. A new constitution of 1871 gave the federal state the new name of German Empire and the Prussian king the title of Emperor. The German Empire retained black, white, and red as its national colours.[31] An ordinance of 1892 dealt with the official use of the colours.

The black-white-red tricolour remained the flag of Germany until the end of the German Empire in 1918, in the final days of World War I.

Weimar Republic (1918–1933)

Following the declaration of the German republic in 1918 and the ensuing revolutionary period, the so-called Weimar Republic was founded in August 1919. To form a continuity between the anti-autocratic movement of the 19th century and the new democratic republic, the old black-red-gold tricolour was designated as the national German flag in the Weimar Constitution in 1919.[32] Only the tiny German principalities of Reuss-Greiz – where the use and layout of the schwarz-rot-gold design had originated some 140 years earlier –, Reuss-Gera, Waldeck-Pyrmont and its republican successor had upheld the 1778-established tradition, and had always continued to use the German colours of black, red, and or (gold) in their flag. As a civil ensign, the black-white-red tricolour was retained, albeit with the new tricolour in the top left corner.

This change was not welcomed by many people in Germany, who saw this new flag as a symbol of humiliation following Germany's defeat in the First World War. In the Reichswehr, the old colours continued to be used in various forms. Many conservatives wanted the old colours to return, while monarchists and the far right were far more vocal with their objections, referring to the new flag with various derogatory names (see Colour above). As a compromise, the old black-white-red flag was reintroduced in 1922 to represent German diplomatic missions abroad.[10]

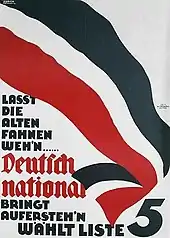

The symbols of Imperial Germany became symbols of monarchist and nationalist protest and were often used by monarchist and nationalist organisations (e.g. Der Stahlhelm, Bund der Frontsoldaten). This included the Reichskriegsflagge (war flag of the Reich), which has been revived in the present for similar use. Many nationalist political parties during the Weimar period—such as the German National People's Party (see poster) and the National Socialist German Workers Party (Nazi Party)—used the imperial colours, a practice that has continued today with the National Democratic Party of Germany.

On 24 February 1924, the organisation Reichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Gold was founded in Magdeburg by the member parties of the Weimar Coalition (Centre, DDP, SPD) and the trade unions. This organisation was formed to protect the fragile democracy of the Weimar Republic, which was under constant pressure by both the far right and far left. Through this organisation, the black-red-gold flag became not only a symbol of German democracy, but also of resistance to political extremism. This was summarised by the organisation's first chairman, Otto Hörsing, who described their task as a "struggle against the swastika and the Soviet star".[33]

In the face of the increasingly violent conflicts between the communists and Nazis, the growing polarisation of the German population and a multitude of other factors, mainly the drastic economic sinking, extreme hyperinflation and corruption of the republic, the Weimar Republic collapsed in 1933 with the Nazi seizure of power (Machtergreifung) and the appointment of Adolf Hitler as German chancellor.

Nazi Germany and World War II (1933–1945)

.svg.png.webp)

After the Nazi Party came to power on 30 January 1933, the black-red-gold flag was swiftly scrapped; a ruling on 12 March established two legal national flags: the reintroduced black-white-red imperial tricolour and the flag of the Nazi Party.[34][35]

On 15 September 1935, one year after the death of Reich President Paul von Hindenburg and Hitler's elevation to the position of Führer, the dual flag arrangement was ended, with the exclusive use of the Nazi flag as the national flag of Germany. One reason may have been the "Bremen incident" of 26 July 1935, in which a group of demonstrators in New York City boarded the ocean liner SS Bremen, tore the Nazi Party flag from the jackstaff, and tossed it into the Hudson River. When the German ambassador protested, US officials responded that the German national flag had not been harmed, only a political party symbol.[36] The new flag law [37] was announced at the annual party rally in Nuremberg,[38] where Hermann Göring claimed the old black-white-red flag, while honoured, was the symbol of a bygone era and under threat of being used by "reactionaries".[39]

The design of the Nazi flag was introduced by Hitler as the party flag in mid-1920, roughly a year before (29 July 1921) he became his political party's leader: a flag with a red background, a white disk and a black swastika in the middle. In Mein Kampf, Hitler explained the process by which the Nazi flag design was created: It was necessary to use the same colours as Imperial Germany, because in Hitler's opinion they were "revered colours expressive of our homage to the glorious past and which once brought so much honour to the German nation." The most important requirement was that "the new flag ... should prove effective as a large poster" because "in hundreds of thousands of cases a really striking emblem may be the first cause of awakening interest in a movement." Nazi propaganda clarified the symbolism of the flag: the red colour stood for the social, white for the movement's national thinking and the swastika for the victory of Aryan humanity and the victory of productive humanity.[40]

An off-centred disk version of the swastika flag was used as the civil ensign on German-registered civilian ships and was used as the jack on Kriegsmarine (the name of the German Navy, 1933–1945) warships.[41] The flags for use on sea had a through and through image, so the "left-facing" and "right-facing" version were each present on one side while the national flag was right-facing on both sides.[42]

From 1933 to at least 1938, the Nazis sometimes "sanctified" swastika flags by touching them with the Blutfahne (blood flag), the swastika flag used by Nazi paramilitaries during the failed Beer Hall Putsch in 1923. This ceremony took place at every Nuremberg Rally. It is unknown whether this tradition was continued after the last Nuremberg rally in 1938.

At the end of World War II, the first law enacted by the Allied Control Council abolished all Nazi symbols and repealed all relevant laws.[43] The possession of swastika flags is forbidden in several countries since then, with the importation or display of them forbidden particularly in Germany.

After World War II (1945–1949)

After the defeat of Germany in World War II, the country was placed under Allied administration. Although there was neither a national German government nor a German flag, German ships were required by international law to have a national ensign of some kind. As a provisional civil ensign of Germany, the Council designated the international signal pennant Charlie representing the letter C ending in a swallowtail, known as the C-Pennant (C-Doppelstander). The Council ruled that "no ceremony shall be accorded this flag which shall not be dipped in salute to warships or merchant ships of any nationality".[44] Similarly, the Japanese civil ensign used immediately following World War II was the signal pennant for the letter E ending in a swallowtail, and the Ryūkyūan civil ensign was a swallowtailed letter D signal pennant.

West of the Oder–Neisse line, the German states were reorganised along the lines of the zones of occupation, and new state governments were established. Within the American zone, the northern halves of the former states of Württemberg and Baden were merged to form Württemberg-Baden in 1946. As its flag, Württemberg-Baden adopted the black-red-gold tricolour.[45] The choice of these colours was not based on the historical use of the tricolour, but the simple addition of gold to Württemberg's colours of red and black.[46] Coincidentally, Baden's colours were red and yellow, so the colour choice could be mistaken for a combination of the two flags. In 1952, Württemberg-Baden became part of the modern German state of Baden-Württemberg, whose flag is black and gold.

Two other states that were created after the war, Rhineland-Palatinate (French zone) and Lower Saxony (British zone), chose to use the black-red-gold tricolour as their flag, defaced with the state's coat of arms.[47][48] These two states were formed from parts of other states, and no colour combinations from these previous states were accepted as a new state flag. This led to the use of the black-red-gold for two reasons: the colours did not relate particularly to any one of the previous states, and using the old flag from the Weimar Republic was intended to be a symbol of the new democracy.[49][50]

Divided Germany (1949–89)

With relations deteriorating between the Soviet Union and the United States, the three western Allies met in March 1948 to merge their zones of occupation and allow the formation of what became the Federal Republic of Germany, commonly known as West Germany. Meanwhile, the eastern Soviet zone became the German Democratic Republic, commonly known as East Germany. During the preparation of the new constitution for West Germany, discussions regarding its national symbols took place in August 1948 during a meeting at Herrenchiemsee. Although there were objections to the creation of a national flag before reunification with the east, it was decided to proceed. This decision was primarily motivated by the proposed constitution by the eastern SED in November 1946,[51] where black-red-gold were suggested as the colours for a future German republic.[52]

.svg.png.webp)

While there were other suggestions for the new flag for West Germany,[53] the final choice was between two designs, both using black-red-gold. The Social Democrats proposed the re-introduction of the old Weimar flag, while the conservative parties such as the CDU/CSU and the German Party proposed a suggestion by Josef Wirmer, a member of the Parlamentarischer Rat (parliamentary council) and future advisor of chancellor Konrad Adenauer. Wirmer suggested a variant of the 1944 "Resistance" flag (using the black-red-gold scheme in a Nordic Cross pattern) designed by his brother and 20 July co-conspirator Josef.[54] The tricolour was ultimately selected, largely to illustrate the continuity between the Weimar Republic and this new German state. With the enactment of the (West) German constitution on 23 May 1949, the black-red-gold tricolour was readopted as the flag for the Federal Republic of Germany.[4]

In 1955, the inhabitants of the French-administered Saar Protectorate voted to join West Germany.[55] Since its establishment as a separate French protectorate in 1947, the Saar had a white Nordic cross on a blue and red background as its flag.[56] To demonstrate the commitment of the Saar to be a part of West Germany, a new flag was selected on 9 July 1956: the black-red-gold tricolour defaced with the new coat of arms, also proposed on this day.[57] This flag came into force on 1 January 1957, upon the establishment of the Saarland as a state of West Germany.

While the use of black-red-gold had been suggested in the Soviet zone in 1946, the Second People's Congress in 1948 decided to adopt the old black-white-red tricolour as a national flag for East Germany. This choice was based on the use of these colours by the National Committee for a Free Germany,[53] a German anti-Nazi organisation that operated in the Soviet Union in the last two years of the war. In 1949, following a suggestion from Friedrich Ebert, Jr., the black-red-gold tricolour was instead selected as the flag of the German Democratic Republic upon the formation of this state on 7 October 1949.[58] From 1949 to 1959, the flags of both West and East Germany were identical. On 1 October 1959, the East German government changed its flag with the addition of its coat of arms.[59] In West Germany, these changes were seen as a deliberate attempt to divide the two Germanys. Displaying this flag in West Germany and West Berlin—where it became known as the Spalterflagge (divider-flag)—was seen as a breach of the constitution and subsequently banned until the late 1960s.

From 1956 to 1964, West and East Germany attended the Winter and Summer Olympic Games as a single team, known as the United Team of Germany. After the East German national flag was changed in 1959, neither country accepted the flag of the other. As a compromise, a new flag was used by the United Team of Germany from 1960 to 1964, featuring the black-red-gold tricolour defaced with white Olympic rings in the red stripe. In 1968 the teams from the two German states entered separately, but both used the same German Olympic flag. From 1972 to 1988, the separate West and East German teams used their respective national flags.

1989–present

After the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, many East Germans cut the coat of arms out of their flags, as Hungarians had done in 1956 and as Romanians would soon do during the fall of Ceaușescu.[60] The widespread act of removing the coat of arms from the East German flag implied the plain black-red-gold tricolour as symbol for a united and democratic Germany. Finally, on 3 October 1990, as the area of the German Democratic Republic was absorbed into the Federal Republic of Germany, the black-red-gold tricolour became the flag of a reunified Germany. In 1998, the Foundation for the Reappraisal of the SED Dictatorship was formed. The duty of this organisation, directly responsible to the federal government, is to examine the consequences of the former East German regime. As its logo, the foundation used an East German flag with the Communist coat of arms cut out.[61]

The old black-white-red tricolour of the German Empire is still used by monarchists and those members of German royalty who long for the peaceful reintroduction of a German democratic monarchy.[62] This use of the old flag is almost completely overshadowed by its prevalent use by the far right; since the aforementioned ban on all Nazi symbolism (e. g. the swastika), the Schutzstaffel's (SS) double sig rune, etc.) is still in effect within today's Germany, the far right have been forced to forego any Nazi flags and instead use the old imperial flag, which the Nazis themselves banned in 1935.[37]

In Germany, the use of the flag and other national symbols has been relatively low for most of the time since the Second World War — a reaction against the widespread use of flags by the Nazi Party and against nationalistic fervour in general, especially that of the Nazis.[63] During the 2006 FIFA World Cup, which took place in Germany, public use of the national flag increased dramatically.[64] This explosion in the flag's occurrence in day-to-day life was initially greeted by many Germans with a mixture of surprise and apprehension.[65] The decades-old fear that German flag-waving and national pride was inextricably associated with its Nazi past was dismissed by the end of the tournament by Germans and non-Germans alike.[66] As many Germans regarded showing the own flag as part of their support for the own team in the tournament, most flags disappeared after the end of a tournament, sometimes due to government decisions.[67] By the time of Germany's World Cup victory in 2014, usage of the German flag increased periodically.[68] In the period that followed, the display of German flag colours, even outside stadiums, was regularly limited to the period of major sporting events. With the rise of nationalist currents (Pegida, AfD, etc.) and their showing of the German flag as a symbol of their nationalism, the flag again became more widespread in everyday life.[68] Mainstream society remains hesitant to use the colours, though.[69]

See also

References

- "Anordnung über die deutschen Flaggen, dated 13.11.1996" [Order concerning the German flags, dated 13 November 1996] (PDF) (in German). Retrieved 14 February 2012.

Die Bundesflagge besteht aus drei gleich breiten Querstreifen, oben schwarz, in der Mitte rot, unten goldfarben [The national flag consists of three horizontal stripes of equal breadth, black at the top, red in the middle, and gold at the bottom]

- http://www.ingeb.org/Lieder/wirhatte.html

- The Flag of Germany Archived 29 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany (23 May 1949). German version and English version (December 2000) (PDF). See Article 22. Retrieved on 24 February 2008. Archived 27 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Federal Government of Germany (7 July 1950). "Anordnung über die deutschen Flaggen" [Arrangement of the German Flag]. documentArchiv.de (in German). Retrieved 9 August 2007.

- Federal Government of Germany (24 May 1968). "§ 124 OWiG: Benutzen von Wappen oder Dienstflaggen" [Administrative Offences Act § 124: Use of crest or official flags] (in German). Retrieved 24 February 2008.

- Federal Government of Germany (13 November 1996). "Anordnung über die deutschen Flaggen" [Arrangement of the German Flag]. Gesetze im Internet (in German). Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- "Flag hoisting formats and terminology (Germany, Austria, and adjacent countries)". Flags of the World. 26 October 2001. Archived from the original on 9 February 2008. Retrieved 24 February 2008.

- Government of the German Reich (11 April 1921). "Verordnung über die deutschen Flaggen" [Regulation on the German Flags]. documentArchiv.de (in German). Retrieved 9 August 2007.

- "Colors of the Flag (Germany)". Flags of the World. 5 August 1998. Retrieved 24 February 2008.

- "Historical Use of the Current Flag". Flags of the World. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- Federal Government of Germany (17 December 2007). "Primärfarben". Corporate Design Documentation (in German). Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- "Styleguide der Bundesregierung". Bundesregierung. Archived from the original on 15 June 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Dreyhaupt, Rüdiger F. (2000). "Flags of the Weimar Republic". Der Flaggenkurier (in German). 11: 3–17.

- (in German) Federal Court of Justice of Germany (16 November 1959). 3 StR 45/59.

- Rabbow, Arnold (1968). "Schwarz–Rot–Gold oder Schwarz–Rot–Gelb?". Neue Heraldische Mitteilungen / Kleeblatt-Jahrbuch (in German). Hanover. 6+7: 30–32.

- Federal Government of Germany (22 March 2005). "Beflaggungserlass der Bundesregierung" (in German). Archived from the original on 16 December 2007. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- "Flag Protocol (Germany)". Flags of the World. 6 February 2002. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- "Holy Roman Empire". Flags of the World. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- "Unidentified 'Rhine Republic' Flag 1806 (Germany)". Flags of the World. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- Rabbow, Arnold (2007). "Schwarz-Rot-Gold: Einheit in Freiheit" [Black-Red-Gold. Unity in Freedom]. Der Flaggenkurier [The Flag Courier] (in German). 25: 41–45.

- (in German) Scheidler, Karl Hermann (5 August 1865) Illustrierte Zeitung, Leipzig, 98

- "German Confederation". Flags of the World. Retrieved 2 March 2008.

- Heinrich Treitschke, History of Germany in the Nineteenth Century, English translation 1917. Volume 3, page 51.

- Heinrich Treitschke, History of Germany in the Nineteenth Century, English translation 1917. Volume 3 Appendixes, page 603.

- "Austria: The Age of Metternich". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2008. Retrieved 5 March 2008.

- "The Hambach Festival". Official website of Hambach Castle. 2007. Archived from the original on 19 August 2004. Retrieved 24 February 2008.

- Frankfurt Parliament (12 November 1848). "Gesetz betreffend die Einführung einer deutschen Kriegs- und Handelsflagge" [Act concerning the introduction of a German navy and merchant flag]. documentArchiv.de (in German). Retrieved 9 August 2007.

- "Constitution of the North German Confederation". documentArchiv.de (in German). 27 June 1867. Retrieved 24 February 2008. See Article 55.

- "Constitution of the German Empire". documentArchiv.de (in German). 16 April 1871. Retrieved 24 February 2008. See Article 55.

- "Constitution of the Weimar Republic". documentArchiv.de (in German). 11 August 1919. Retrieved 24 February 2008. See Article 3.

- von Hindenburg, Paul (12 March 1933). "Erlaß des Reichspräsidenten über die vorläufige Regelung der Flaggenhissung" [Decree of the President for the provisional regulation of raising flags]. documentArchiv.de (in German). Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- Fornax. "The German Swastika Flag 1933–1945". Historical flags of our ancestors. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- Brian Leigh Davis: Flags & standards of the Third Reich, Macdonald & Jane's, London 1975, ISBN 0-356-04879-9

- Government of the German Reich (15 September 1935). "Reichsflaggengesetz" [Reich Flag Act]. documentArchiv.de (in German). Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- GERMANY: Little Man, Big Doings, TIME Magazine, 23 September 1935

- Statement by Hermann Göring, quoted in the Völkischer Beobachter (17 September 1935) (in German)

- Nazi propaganda pamphlet "The Life of the Führer"

- Government of the German Reich (20 December 1933). "Verordnung über die vorläufige Regelung der Flaggenführung auf Kauffahrteischiffen". documentArchiv.de (in German). Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- The German swastika flag 1933–1945

- Allied Control Council (30 August 1945). "Law N° 1 from the Control Council for Germany: Repealing of Nazi Laws". European Navigator. Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- Allied Control Council (30 November 1946). "Law No. 39 of the Allied Control Commission". Flags of the World. Archived from the original on 12 March 2008. Retrieved 26 February 2008. See Article 1 #3.

- "Constitution of Württemberg-Baden". Verfassungen der Welt. 30 November 1946. Retrieved 24 February 2008. See Article 45 (in German)

- "Württemberg-Baden 1947–1952 (Germany)". Flags of the World. Archived from the original on 12 March 2008. Retrieved 24 February 2008. Contains quotation from discussion of the constitution committee.

- "Constitution of Rhineland-Palatinate". Verfassungen der Welt (in German). 18 May 1947. Archived from the original on 15 February 2008. Retrieved 24 February 2008.

- "Preliminary constitution of Lower Saxony". Verfassungen der Welt (in German). 13 April 1951. Archived from the original on 11 March 2008. Retrieved 24 February 2008. See Article 1 #2

- "Rhineland-Palatinate (Germany)". Flags of the World. Retrieved 3 March 2008.

- "Lower Saxony (Germany)". Flags of the World. Retrieved 3 March 2008.

- Friedel, Alois (1968). Deutsche Staatssymbole [German state symbols] (in German). Athenäum-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7610-5115-3.

- "SED-proposed constitution of the German Democratic Republic". documentArchiv.de. 14 November 1946. Retrieved 24 February 2008. (in German)

- "Proposals 1944–1949 (Germany)". Flags of the World. Retrieved 24 February 2008.

- Rabbow, Arnold (May–August 1983). "A Flag Against Hitler. The 1944 National Flag Proposal of the German Resistance Movement". Flag Bulletin. 100.

- "The Saar referendum". European Navigator. 23 October 1955. Retrieved 24 February 2008.

- "Constitution of the Saarland". documentArchiv.de. 15 December 1947. Retrieved 24 February 2008. See Article 61. (in German)

- (in German) Government of the Saarland (9 July 1956) Gesetz Nr. 508 über die Flagge des Saarlandes and Gesetz Nr. 509 über das Wappen des Saarlandes

- "Constitution of the German Democratic Republic". documentArchiv.de (in German). 7 October 1949. Retrieved 24 February 2008. See Article 2.

- Government of the German Democratic Republic (1 October 1959). "Gesetz zur Änderung des Gesetzes über das Staatswappen und die Staatsflagge der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik". documentArchiv.de (in German). Retrieved 24 February 2008.

- Guibernau, Montserrat (26 July 2013). Belonging: Solidarity and Division in Modern Societies. Polity Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-0745655079.

- Information pamphlet Archived 27 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine by the Foundation for the Reappraisal of the SED Dictatorship. Retrieved on 9 March 2008.

- Home page of monarchist organisation Tradition und Leben. See German section for more detailed text. Retrieved on 24 February 2008.

- Sontheimer, Michael (29 June 2006). "Dr. Strangelove: How Germans Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Flag". Spiegel Online. Retrieved 5 March 2008.

- Young, Marc (14 June 2006). "Germany flies the flag". Spiegel Online. Retrieved 24 February 2008.

- Bernstein, Richard (14 June 2006). "In World Cup Surprise, Flags Fly With German Pride". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 March 2008.

- Crossland, David (10 July 2006). "Germany's World Cup Recovery: From Humorless to Carefree in 30 Days". Spiegel Online. Retrieved 5 March 2008.

- "Nach der WM: Die Party ist aus: Flaggen müssen weg". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. 11 July 2006. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Borcholte, Andreas (12 June 2016). "EM-Patriotismus: Schwarz-rot-kompliziert". Spiegel Online. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Lau, Mariam (17 October 2018). "Deutschlandfahne: Farbe bekennen". Zeit Online. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)