President of Germany

The president of Germany, officially the Federal President of the Federal Republic of Germany (German: Bundespräsident der Bundesrepublik Deutschland),[2] is the head of state of Germany.

| Federal President of the Federal Republic of Germany

Bundespräsident der Bundesrepublik Deutschland | |

|---|---|

Logo | |

| |

| Style | His Excellency (in international relations only) |

| Status | Head of State |

| Residence | Schloss Bellevue (Berlin) Villa Hammerschmidt (Bonn) |

| Appointer | Federal Convention |

| Term length | Five years Renewable once, consecutively |

| Constituting instrument | Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany |

| Precursor | The Reichspräsident |

| Inaugural holder | Theodor Heuss |

| Formation | 24 May 1949 |

| Salary | 249,000 € annually[1] |

| Website | www |

Under the 1949 constitution (Basic Law) Germany has a parliamentary system of government in which the chancellor (similar to a prime minister or minister president in other parliamentary democracies) is the head of government. The president has far-reaching ceremonial obligations, but also the right and duty to act politically.[3] They can give direction to general political and societal debates and has some important "reserve powers" in case of political instability (such as those provided for by Article 81 of the Basic Law).[4] The president also holds the prerogative to grant pardons on behalf of the federation. The German presidents, who can be elected to two consecutive five-year terms, have wide discretion about how they exercise their official duties.[5]

Under Article 59 (1) of the Basic Law (German Constitution), the president represents the Federal Republic of Germany in matters of international law, concludes treaties with foreign states on its behalf and accredits diplomats.[6] Furthermore, all federal laws must be signed by the president before they can come into effect, but usually they only veto a law if they believe it to violate the constitution.

The president, by his actions and public appearances, represents the state itself, its existence, legitimacy, and unity. The president enjoys higher ranking at official functions than the chancellor, as he is the actual head of state. The president's role is integrative and includes the control function of upholding the law and the constitution. It is a matter of political tradition – not legal restrictions – that the president generally does not comment routinely on issues in the news, particularly when there is some controversy among the political parties.[7] This distance from day-to-day politics and daily governmental issues allows the president to be a source of clarification, to influence public debate, voice criticism, offer suggestions and make proposals. In order to exercise this power, they traditionally act above party politics.[8]

The current officeholder is Frank-Walter Steinmeier who was elected on 12 February 2017 and started his first five-year term on 19 March 2017.

Election

The president is elected for a term of five years by secret ballot, without debate, by a specially convened Federal Convention which mirrors the aggregated majority position in the Bundestag (the federal parliament) and in the parliaments of the 16 German states. The convention consists of all Bundestag members, as well as an equal number of electors elected by the state legislatures in proportion to their respective populations. Since reunification, all Federal Conventions have had more than 1200 members, as the Bundestag has always had more than 600 parliamentarians since then. It is not required that state electors are chosen from the members of the state legislature; often some prominent citizens are chosen.

The German constitution, the Basic Law, requires that the convention be convened no later than 30 days before the scheduled expiry of the sitting president's term or 30 days after a premature expiry of a president's term. The body is convened and chaired by the president of the Bundestag. From 1979 to 2009, all these conventions were held on 23 May, the anniversary of the foundation of the Federal Republic in 1949. However, the two most recent elections before 2017 were held on different dates after the incumbent presidents, Horst Köhler and Christian Wulff, resigned before the end of their terms, in 2010 and 2012 respectively.

In the first two rounds of the election, the candidate who achieves an absolute majority is elected. If, after two votes, no single candidate has received this level of support, in the third and final vote the candidate who wins a plurality of votes cast is elected.

The result of the election is often determined by party politics. In most cases, the candidate of the majority party or coalition in the Bundestag is considered to be the likely winner. However, as the members of the Federal Convention vote by secret ballot and are free to vote against their party's candidate, some presidential elections were considered open or too close to call beforehand because of relatively balanced majority positions or because the governing coalition's parties could not agree on one candidate and endorsed different people, as they did in 1969, when Gustav Heinemann won by only 6 votes on the third ballot. In other cases, elections have turned out to be much closer than expected. For example, in 2010, Wulff was expected to win on the first ballot, as the parties supporting him (CDU, CSU and FDP) had a stable absolute majority in the Federal Convention. Nevertheless, he failed to win a majority in the first and second ballots, while his main opponent Joachim Gauck had an unexpectedly strong showing. In the end Wulff obtained a majority in the third ballot. If the opposition has turned in a strong showing in state elections, it can potentially have enough support to defeat the chancellor's party's candidate; this happened in the elections in 1979 and 2004. For this reason, presidential elections can indicate the result of an upcoming general election. According to a long-standing adage in German politics, "if you can create a President, you can form a government."

Past presidential elections

| Election | Date | Site | Ballots | Winner (endorsing parties) [lower-alpha 1] | Electoral votes (percentage) | Runner-up (endorsing parties) [lower-alpha 2] | Electoral votes (percentage) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Federal Convention | 12 September 1949 | Bonn | 2 | Theodor Heuss (FDP, CDU, CSU) | 416 (51.7%) | Kurt Schumacher (SPD) | 312 (38.8%) |

| 2nd Federal Convention | 17 July 1954 | West Berlin | 1 | Theodor Heuss (FDP, CDU, CSU, SPD) | 871 (85.6%) | Alfred Weber (KPD) | 12 (1.2%) |

| 3rd Federal Convention | 1 July 1959 | West Berlin | 2 | Heinrich Lübke (CDU, CSU) | 526 (50.7%) | Carlo Schmid (SPD) | 386 (37.2%) |

| 4th Federal Convention | 1 July 1964 | West Berlin | 1 | Heinrich Lübke (CDU, CSU, SPD) | 710 (68.1%) | Ewald Bucher (FDP) | 123 (11.8%) |

| 5th Federal Convention | 5 March 1969 | West Berlin | 3 | Gustav Heinemann (SPD, FDP) | 512 (49.4%) | Gerhard Schröder (CDU, CSU, NPD) | 506 (48.8%) |

| 6th Federal Convention | 15 May 1974 | Bonn | 1 | Walter Scheel (FDP, SPD) | 530 (51.2%) | Richard von Weizsäcker (CDU, CSU) | 498 (48.1%) |

| 7th Federal Convention | 23 May 1979 | Bonn | 1 | Karl Carstens (CDU, CSU) | 528 (51%) | Annemarie Renger (SPD) | 431 (41.6%) |

| 8th Federal Convention | 23 May 1984 | Bonn | 1 | Richard von Weizsäcker (CDU, CSU, FDP, SPD) | 832 (80%) | Luise Rinser (Greens) | 68 (6.5%) |

| 9th Federal Convention | 23 May 1989 | Bonn | 1 | Richard von Weizsäcker (CDU, CSU, FDP, SPD) | 881 (84.9%) | none | 108 (10.4%) no-votes |

| 10th Federal Convention | 23 May 1994 | Berlin | 3 | Roman Herzog (CDU, CSU) | 696 (52.6%) | Johannes Rau (SPD) | 605 (45.7%) |

| 11th Federal Convention | 23 May 1999 | Berlin | 2 | Johannes Rau (SPD, Alliance 90/Greens) | 690 (51.6%) | Dagmar Schipanski (CDU, CSU) | 572 (42.8%) |

| 12th Federal Convention | 23 May 2004 | Berlin | 1 | Horst Köhler (CDU, CSU, FDP) | 604 (50.1%) | Gesine Schwan (SPD, Alliance90/Greens) | 589 (48.9%) |

| 13th Federal Convention | 23 May 2009 | Berlin | 1 | Horst Köhler (CDU, CSU, FDP, Free Voters) | 613 (50.1%) | Gesine Schwan (SPD, Alliance 90/Greens) | 503 (41.1%) |

| 14th Federal Convention | 30 June 2010 | Berlin | 3 | Christian Wulff (CDU, CSU, FDP) | 625 (50.2%) | Joachim Gauck (SPD, Alliance 90/Greens) | 494 (39.7%) |

| 15th Federal Convention | 18 March 2012 | Berlin | 1 | Joachim Gauck (CDU, CSU, FDP, SPD, Alliance 90/Greens, Free Voters, SSW) | 991 (79.9%) | Beate Klarsfeld (The Left) | 126 (10.2%) |

| 16th Federal Convention | 12 February 2017 | Berlin | 1 | Frank-Walter Steinmeier (SPD, CDU, CSU, Alliance 90/Greens, FDP, SSW) | 931 (74.3%) | Christoph Butterwegge (The Left) | 128 (10.2%) |

- governing parties in bold

- governing parties in bold

Qualifications

The office of president is open to all Germans who are entitled to vote in Bundestag elections and have reached the age of 40, but no one may serve more than two consecutive five-year terms. As yet (2017), only four presidents (Heuss, Lübke, von Weizsäcker and Köhler) have been elected for a second term and only two of them (Heuss and von Weizsäcker) completed those terms, while Lübke and Köhler resigned during their second term. The president must not be a member of the federal government or of a legislature at either the federal or state level.

Oath

On taking office the president must take the following oath, stipulated by Article 56 of the Basic Law, in a joint session of the Bundestag and the Bundesrat (it is the only event that demands such a joint session constitutionally). The religious references may optionally be omitted.

I <name> swear that I will dedicate my efforts to the well-being of the German people, enhance their benefits, avert harm from them, uphold and defend the Constitution and the statutes of the Federation, fulfil my duties conscientiously, and do justice to all. (So help me God.)[9]

German constitutional law does not consider oaths of office as constitutive but only as affirmative. This means that the president does not have to take the oath in order to enter office and use it's constitutional powers. Nevertheless, a persistent refusal to take the oath is considered to be an impeachable offence by legal scholars.[10] In practice, the oath is usually administered during the first weeks of a president's term on a date convenient for a joint session of the Bundestag and the Bundesrat. If a president is re-elected for a second consecutive term, they do not take the oath again.

Duties and functions

The president is involved in the formation of the Federal Government and remains in close cooperation with it. Basically, the president is free to act on his own discretion. However, according to Article 58 of the German constitution, the decrees, and directives of the president require the countersignature of the chancellor or the corresponding federal minister in charge of the respective field of politics. This rule ensures the coherence of government action, similar to the system of checks and balances in the United States of America. There is no need for a countersignature if the president proposes, appoints or dismisses the chancellor, convenes or dissolves the Bundestag according to Article 63, declares a legislative state of emergency, calls on a Chancellor and ministers to remain in office after the end of a Chancellor's term until a successor is elected or exercises his right to pardon on behalf of the federation, as these are exclusive powers of the president.

Therefore, the president also receives the chancellor regularly for talks on current policy issues. German presidents also hold talks with individual federal ministers and other senior officials at their own discretion. The "Head of the Office of the President" represents the will and views of the president in the meetings of the Federal Cabinet and reports back to the president.[11]

The president's most prominent powers and duties include:[11]

- Proposing the chancellor to the Bundestag.

- Appointing and dismissing the chancellor and their cabinet ministers

- Dissolving the Bundestag under certain circumstances

- Declaring the legislative state of emergency under certain circumstances

- Convening the Bundestag

- Signing and promulgating laws or vetoing them under certain circumstances

- Appointing and dismissing federal judges, federal civil servants, and commissioned and non-commissioned officers of the Armed Forces

- Exercising the power to pardon individual offenders on behalf of the Federation

- Awarding honors on behalf of the Federation

- Representing Germany at home and abroad

Appointment of the Federal Government

After the constitution of every new elected Bundestag, which automatically ends the term of the chancellor, and in every other case in which the office of chancellor has fallen vacant (death or resignation), the president proposes an individual as chancellor and must then, provided they are subsequently elected by a majority of all members of the current Bundestag (the so-called Chancellor-majority) on the first ballot, appoint them to the office. However, the Bundestag is free to disregard the president's proposal (which has, as of 2020, never happened), in which case the parliament must within 14 days elect another individual, whom the parties in the Bundestag can now propose themselves, to the post with the same so-called Chancellor-majority, whom the president is then obliged to appoint. If the Bundestag does not manage to do so, on the 15th day after the first ballot the Bundestag must hold one last ballot: if an individual is elected with the Chancellor-majority, the president is obliged to appoint them. If not, the president can either appoint as chancellor the individual who received a plurality of votes on this last ballot or dissolves the Bundestag. The president can dismiss the chancellor, but only if the Bundestag passes a constructive vote of no confidence, electing a new chancellor with the Chancellor-majority at the same time.[12] If this occurs, the president must dismiss the chancellor and appoint the successor elected by the Bundestag.[12]

The president appoints and dismisses the remaining members of the federal government upon the proposal of the chancellor. This means that the president can appoint only candidates presented by the chancellor. It is unclear, whether the president can refuse to dismiss or appoint a federal minister proposed by the chancellor, as no president has ever done so.

In practice, the president only proposes a person as chancellor who has previously garnered a majority support in coalition talks and traditionally does not interfere in those talks. However, after the "Jamaica coalition" talks failed in late 2017, President Steinmeier invited several Bundestag party leaders to try to still bring them together to form a working government.

Other appointments

The president appoints federal judges, federal civil servants, and military officers.

Dissolution of the Bundestag

In the event that the Bundestag elects an individual for the office of chancellor by a plurality of votes, rather than a majority, on the 15th day of the election process, the president can, at their discretion, either appoint that individual as chancellor or dissolve the Bundestag, triggering a new election. In the event that a vote of confidence is defeated in the Bundestag, and the incumbent chancellor proposes a dissolution, the president may, at his discretion, dissolve the body within 21 days. As of 2010, this power has only been applied three times in the history of the Federal Republic. In all three occurrences, it is doubtful whether the motives for that dissolution were in accordance with the constitution's intentions. Each time the incumbent chancellor called for the vote of confidence with the stated intention of being defeated, in order to be able to call for new elections before the end of their regular term, as the Basic Law does not give the Bundestag a right to dissolve itself. The most recent occurrence was on 1 July 2005, when Chancellor Gerhard Schröder asked for a vote of confidence, which was defeated.[13]

Promulgation of the law

All federal laws must be signed by the president before they can come into effect.[14] The president may refuse to sign the law, thus effectively vetoing it. In principle, the president has the full veto authority on any bill, but this, however, is not how past presidents handled their power.[15] Usually, the president checks if the law was passed according to the order mandated by the Constitution and/or if the content of the law is constitutional. Only in cases in which the incumbent president had serious doubts about the constitutionality of a bill laid before him, he has refused to sign it. It also has to be stated that the presdident may at his own discretion sign such a "vetoed" bill at any later time, if for example the Basic Law has been changed in the relevant aspect or if the bill in question has been amended according to his concerns, because his initial refusal to sign a bill is not technically a final veto.

As yet (2020), this has happened only nine times and no president has done it more often than two times during his term:

- in 1951 Theodor Heuss vetoed a bill concerning income and corporation taxes, because it lacked the consent of the Bundesrat (in Germany some bills at the federal level need the consent of the Bundesrat, and some do not, which can be controversial at times).

- in 1961 Heinrich Lübke refused to sign a bill concerning business and workforce trades he believed to be unconstitutional, because of a violation of the free choice of job.

- in 1969 Gustav Heinemann vetoed the "Engineer Act", because he believed this legislative area to be under the authority of the states.

- in 1970 Gustav Heinemann refused to sign the "Architects Act" for the same reason.

- in 1976 Walter Scheel vetoed a bill about simplification measures regarding the conscientious objection of conscription, because it lacked the - in his opinion necessary - consent of the Bundesrat.

- in 1991 Richard von Weizsäcker refused to sign an amendment to the "Air Traffic Act" allowing the privatization of the air traffic administration, which he believed to be unconstitutional. He signed the bill later after the "Basic Law" was changed in this aspect.

- in 2006 Horst Köhler vetoed a bill concerning flight control, because he believed it to be unconstitutional.

- later the same year Horst Köhler vetoed the "Consumer Information Act" for the same reason.

- in 2020 Frank-Walter Steinmeier refused to sign the "Hate Speech Act" because of concerns about its constitutionality. In a letter sent to the Bundesrat, he stated his intent to sign the bill, if accordingly amended in a reasonable time.[16]

Karl Carstens, Roman Herzog, Johannes Rau, Christian Wulff and Joachim Gauck have signed and promulgated all bills during their respective terms.[17]

Foreign relations

The president represents Germany in the world (Art. 59 Basic Law), undertakes foreign visits and receives foreign dignitaries. They also conclude treaties with foreign nations (which do not come into effect until affirmed by the Bundestag), accredit German diplomats and receive the letters of accreditation of foreign diplomats.

Pardons and honours

According to Article 60 (2) of the German Constitution, the president has the power to pardon. This means the president "has the authority to revoke or commute penal or disciplinary sentences in individual cases. The federal president cannot, however, issue an amnesty waiving or commuting sentences for a whole category of offenses. That requires a law enacted by the Bundestag in conjunction with the Bundesrat. Due to the federal structure of Germany the federal president is only responsible for dealing with certain criminal matters (e.g. espionage and terrorism) and disciplinary proceedings against federal civil servants, federal judges, and soldiers".[18]

It is customary that the federal president becomes the honorary godfather of the seventh child in a family if the parents wish it. He also sends letters of congratulations to centenarians and long-time married couples.[19]

Legislative state of emergency

Article 81 makes it possible to enact a law without the approval of the Bundestag: if the Bundestag rejects a motion of confidence, but a new chancellor is not elected nor is the Bundestag dissolved, the chancellor can declare a draft law to be "urgent". If the Bundestag refuses to approve the draft, the cabinet can ask the federal president to declare a "legislative state of emergency" (Gesetzgebungsnotstand) with regard to that specific law proposal.

After the declaration of the president, the Bundestag has four weeks to discuss the draft law. If it does not approve it the cabinet can ask the Federal Council for approval. After the consent of the Federal Council is secured, the draft law becomes law.

There are some constraints on the "legislative state of emergency". After a president has declared the state of emergency for the first time, the government has only six months to use the procedure for other law proposals. Given the terms provided by the constitution, it is unlikely that the government can enact more than one other draft law in this way.

Also, the emergency has to be declared afresh for every proposal. This means that the six months are not a period in which the government together with the president and the Federal Council simply replaces the Bundestag as lawgiver. The Bundestag remains fully competent to pass laws during these six months. The state of emergency also ends if the office of the chancellor ends. During the same term and after the six months, the chancellor cannot use the procedure of Article 81 again.

A "legislative state of emergency" has never been declared. In case of serious disagreement between the chancellor and the Bundestag, the chancellor resigns or the Bundestag faces new elections. The provision of Article 81 is intended to assist the government for a short time, but not to use it in crisis for a longer period. According to constitutional commentator Bryde, Article 81 provides the executive (government) with the power to "enable decrees in a state of emergency" (exekutives Notverordnungsrecht), but for historical reasons the constitution avoided this expression.[20]

Politics and influence

Though candidates are usually selected by a political party or parties, the president nonetheless is traditionally expected to refrain from being an active member of any party after assuming office. Every president to date, except Joachim Gauck, has suspended his party membership for the duration of his term. Presidents have, however, spoken publicly about their personal views on political matters. The very fact that a president is expected to remain above politics usually means that when he does speak out on an issue, it is considered to be of great importance. In some cases, a presidential speech has dominated German political debate for a year or more.[21]

Reserve powers

According to article 81 of the German constitution, the president can declare a "Legislation Emergency" and allow the federal government and the Bundesrat to enact laws without the approval of the Bundestag. He also has important decisive power regarding the appointment of a chancellor who was elected by plurality only, or the dissolution of the Bundestag under certain circumstances.

It is also theoretically possible, albeit a drastic step which has not happened since 1949, that the president refuses to sign legislation merely because he disagrees with its content, thus vetoing it, or refuse to approve a cabinet appointment.[22] In all cases in which a bill was not signed by the federal president, all presidents have claimed that the bill in question was manifestly unconstitutional. For example, in the autumn of 2006, President Köhler did so twice within three months. Also, in some cases, a president has signed a law while asking that the political parties refer the case to the Federal Constitutional Court in order to test the law's constitutionality.

Succession

_09.jpg.webp)

The Basic Law did not create an office of Vice President, but designated the president of the Bundesrat (by constitutional custom the head of government of one of the sixteen German states, elected by the Bundesrat in a predetermined order of annual alternation) as deputy of the president of Germany (Basic Law, Article 57). If the office of president falls vacant, they temporarily assume the powers of the president and acts as head of state until a successor is elected, but does not assume the office of president as such (which would be unconstitutional, as no member of a legislature or government at federal or state level can be president at the same time). While doing so, they do not continue to exercise the role of chair of the Bundesrat.[23] If the president is temporarily unable to perform his duties (this happens frequently, for example if the president is abroad on a state visit), he can at his own discretion delegate his powers or parts of them to the president of the Bundesrat.[24]

If the president dies, resigns or is otherwise removed from office, a successor is to be elected within thirty days. Horst Köhler, upon his resignation on May 31, 2010, became the first president to trigger this re-election process. Jens Böhrnsen, President of the Senate and Mayor of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen and at the time President of the Bundesrat, assumed the powers and duties of head of state.[25] Similarly, when Christian Wulff resigned in 2012, it was Horst Seehofer, Minister President of Bavaria, as President of the Bundesrat, who assumed the powers and duties of head of state. When Heinrich Lübke, on the other hand, announced his resignation in 1968, it only came into effect the following year, a mere three months before the scheduled end of his term and after the expedited election of his successor. Back in 1949 Karl Arnold, at the time Minister President of North Rhine-Westphalia and President of the Bundesrat, also acted as head of state for a few days: after the Basic Law had come into effect and he himself was elected as President of the Bundesrat, the first President of Germany was not yet elected and the office therefore vacant.

None of these three presidents of the Bundesrat acting as head of state, has used any of the more important powers of the president, as for example vetoing a law or dissolving the Bundestag, although they would have been entitled to do so under the same conditions as the president.

Impeachment and removal

While in office, the president enjoys immunity from prosecution and cannot be voted out of office or recalled. The only mechanism for removing the president is impeachment by the Bundestag or Bundesrat for willfully violating German law. In both bodies a two-thirds majority is required. Once the Bundestag or the Bundesrat impeaches the president, the Federal Constitutional Court is charged with determining if they are guilty of the offence. If the charge is sustained, the court has the authority to remove the president from office.

Presidential office and symbols

_(6272414834).jpg.webp)

Residences and office

The official residence of the president is Bellevue Palace in Berlin. The president's second official residence is the Hammerschmidt Villa in Bonn, the former capital city of West Germany.

The Office of the President (Bundespräsidialamt) is a supreme federal authority. It organizes the president's work, supports the president in the performance of his duties as Head of State and coordinates his working relationships with other parts of the German government and administration. Its top official, who takes precedence over all other German state secretaries, is the Head of the Office of the President (Chef des Bundespräsidialamts).

The office and its staff advise the president, informs them of all developments in domestic and foreign affairs and carries out the instructions of the president or forwards these to the corresponding ministry or authority.[26]

Transportation

The president's car is usually black, made in Germany and has the numberplate "0 – 1" with the presidential standard on the right wing of the car. The president also uses a VIP helicopter operated by the Federal Police and VIP aircraft (Bombardier Global 5000, Airbus A319CJ, Airbus A310 or A340) operated by the Executive Transport Wing of the German Air Force. When the president is on board, the flight's callsign is "German Airforce 001".

Presidential standard

The standard of the president of Germany was adopted on 11 April 1921, and used in this design until 1933. A slightly modified version also existed from 1926, that was used in addition to the 1921 version. In 1933, these versions were both replaced by another modified version, that was used until 1935.

The Weimar-era presidential standard from 1921 was adopted again as presidential standard by a decision by President Theodor Heuss on 20 January 1950, when he also formally adopted other Weimar-era state symbols including the coat of arms. The eagle (Reichsadler, now called Bundesadler) in the design that was used in the coat of arms and presidential standard in the Weimar Republic and today was originally introduced by a decision by President Friedrich Ebert on 11 November 1919.

History

The modern-day position of German president is significantly different from the Reich President of the Weimar Republic – a position which held considerable power and was regarded as an important figure in political life.[27]

Weimar Republic

The position of President of Germany was first established by the Weimar Constitution, which was drafted in the aftermath of World War I and the abdication of Emperor Wilhelm II in 1918. In Germany the new head of state was called the Reichspräsident.

Friedrich Ebert (SPD) served as Germany's first president, followed by Paul von Hindenburg. The office effectively came to an end upon Hindenburg's death in 1934 and its powers merged with those of chancellor. Adolf Hitler now ruled Germany as "Führer und Reichskanzler", combining his previous positions in party and government. However, he did officially become President;[28] the office was not abolished (though the constitutionally mandated presidential elections every seven years did not take place in the Nazi era) and briefly revived at the end of the Second World War when Hitler appointed Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz as his successor as "President of Germany". Dönitz agreed to the surrender to the Allies and was arrested a few days later.[29]

The Weimar Constitution created a semi-presidential system in which power was divided between the president, a cabinet and a parliament. The president enjoyed far greater power than the current president and had an active political role, rather than a largely ceremonial one. The influence of the president also increased greatly as a result of the instability of the Weimar period. The president had authority to appoint the chancellor and could dismiss the entire cabinet at any time. However, it was also necessary for the cabinet to enjoy the confidence of the Reichstag (parliament) because it could be removed by a vote of no confidence.[30] All bills had to receive the signature of the president to become law and, although he did not have an absolute veto on legislation, he could insist that a law be submitted for the approval of voters in a referendum. The president also had authority to dissolve the Reichstag, conduct foreign affairs, and command the armed forces. Article 48 of the constitution also provided the president sweeping powers in the event of a crisis. If there was a threat to "public order and security" he could legislate by decree and suspend civil rights.

The Weimar constitution provided that the president be directly elected and serve a seven-year term. The election involved a form of the two-round system. However the first president was elected by the National Assembly and subsequently only two direct presidential elections actually occurred. These were the election of Paul von Hindenburg in 1925 and his re-election in 1932.

The system created by the Weimar constitution led to a number of problems. In particular, the fact that the president could appoint the cabinet, while the Reichstag had only a power of dismissal, created a high cabinet turn-over as ministers were appointed by the president only to be dismissed by the Reichstag shortly afterwards. Eventually Hindenburg stopped trying to appoint cabinets that enjoyed the confidence of the Reichstag and ruled by means of three "presidential cabinets" (Präsidialkabinette). Hindenburg was also able to use his power of dissolution to by-pass the Reichstag. If the Reichstag threatened to censure his ministers or revoke one of his decrees he could simply dissolve the body and be able to govern without its interference until elections had been held. This led to eight Reichstag elections taking place in the 14 years of the Republic's existence; only one parliamentary term, that of 1920–1924, was completed without elections being held early.

German Democratic Republic ("East Germany")

Socialist East Germany established the office of a head of state with the title of President of the Republic (German: Präsident der Republik) in 1949, but abandoned the office with the death of the first president, Wilhelm Pieck, in 1960 in favour of a collective head of state. All government positions of the East German socialist republic, including the presidency, were appointed by the ruling Socialist Unity Party of Germany.

Federal Republic of Germany ("West Germany", 1949–1990)

With the promulgation of the Grundgesetz in 1949, the office of President of the Federal Republic (in German: Bundespräsident) was created in West Germany. Partly due to the misuse of presidential powers in the Weimar Republic, the office's powers were significantly reduced. Not only is he indirectly elected, but most of the real power was transferred to the chancellor.

Because the reunification of Germany in 1990 was accomplished by the five East German states joining the Federal Republic, the president became the president of all German states without the establishment of a new presidential office.

List of presidents

Twelve persons have served as President of the Federal Republic of Germany. Six of them were members of the CDU (Lübke, Carstens, von Weizsäcker, Herzog, Köhler, Wulff), three were members of the SPD (Heinemann, Rau, Steinmeier), two were members of the FDP (Heuss, Scheel) and one was independent (Gauck). Four presidents were ministers in the federal government before entering office (Lübke Agriculture, Heinemann Justice, Scheel, Steinmeier Foreign Affairs), two of them (Scheel, Steinmeier) having been Vice Chancellor of Germany. Three were head of a state government (von Weizsäcker West Berlin, Rau North Rhine-Westphalia, Wulff Lower Saxony), Rau having been President of the Bundesrat. Two were members of the Bundestag (Heuss, Carstens), Carstens having been President of the Bundestag. One was president of the Federal Constitutional Court (Herzog), director of the IMF (Köhler) and Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Records (Gauck). Only four presidents (Heuss, Lübke, von Weizsäcker, Köhler) have been re-elected for a second five-year-term and only two of those (Heuss, von Weizsäcker) served the full ten years. Christian Wulff served the shortest tenure (1 year, 7 months and 18 days) of all presidents.

The president is (according to Art. 57 GG) deputised by the president of the Bundesrat who can perform any of the president's duties, if the president is temporarily unable to do so and delegates these duties to them (this frequently happens during state visits), or if the Presidency falls vacant, in which case he becomes acting head of state (not "(acting) President") until a successor is elected, which has to happen within thirty days. This has happened three times:

- in 1949 Karl Arnold acted as head of state after the Grundgesetz came into effect on 7 September 1949 and before Theodor Heuss was elected by the 1st Federal Convention on 12 September 1949.

- in 2010 Jens Böhrnsen acted as head of state after the resignation of Horst Köhler and before the election of Christian Wulff.

- in 2012 Horst Seehofer acted as head of state after the resignation of Christian Wulff and before the election of Joachim Gauck.

- Political Party

FDP (2) CDU (6) SPD (3) None (1)

| № | Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) (Home State) |

Previous service | Term of Office | Political Party | Deputies (Presidents of the Bundesrat, according to Art. 57 GG). Presidents of the Bundesrat, who acted as head of state because of a vacancy, in bold | Notable decisions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Took Office | Left Office | ||||||||

| President of the Federal Republic of Germany (Bundespräsident) | |||||||||

| 1 |  |

Theodor Heuss (1884–1963) (Württemberg-Baden, since 1952 part of Baden-Württemberg) |

Member of the Bundestag (1949) | 12 September 1949 | 12 September 1959 | FDP | Karl Arnold (1949–1950), Hans Ehard (1950–1951), Hinrich Wilhelm Kopf (1951–1952), Reinhold Maier (1952–1953), Georg August Zinn (1953–1954), Peter Altmeier (1954–1955), Kai-Uwe von Hassel (1955–1956), Kurt Sieveking (1956–1957), Willy Brandt (1957–1958), Wilhelm Kaisen (1958–1959) | vetoed one bill | |

| 2 |  |

Heinrich Lübke (1894–1972) (North Rhine-Westphalia) |

Federal Minister of Agriculture (1953–1959) | 13 September 1959 | 30 June 1969 (resigned) |

CDU | Wilhelm Kaisen (1959), Franz Josef Röder (1959–1960), Franz Meyers (1960–1961), Hans Ehard (1961–1962), Kurt Georg Kiesinger (1962–1963), Georg Diederichs (1963–1964), Georg August Zinn (1964–1965), Peter Altmeier (1965–1966), Helmut Lemke (1966–1967), Klaus Schütz (1967–1968), Herbert Weichmann (1968–1969) | vetoed one bill | |

| 3 |  |

Gustav Heinemann (1899–1976) (North Rhine-Westphalia) |

Federal Minister of Justice (1966–1969) | 1 July 1969 | 30 June 1974 | SPD | Herbert Weichmann (1969), Franz Josef Röder (1969–1970), Hans Koschnick (1970–1971), Heinz Kühn (1971–1972), Alfons Goppel (1972–1973), Hans Filbinger (1973–1974) | vetoed two bills and dissolved the Bundestag in 1972 | |

| 4 |  |

Walter Scheel (1919–2016) (North Rhine-Westphalia) |

Vice Chancellor of Germany (1969–1974) Federal Minister of Foreign Affairs (1969–1974) |

1 July 1974 | 30 June 1979 | FDP | Hans Filbinger (1974), Alfred Kubel (1974–1975), Albert Osswald (1975–1976), Bernhard Vogel (1976–1977), Gerhard Stoltenberg (1977–1978), Dietrich Stobbe (1978–1979) | vetoed one bill | |

| 5 | .jpg.webp) |

Karl Carstens (1914–1992) (Schleswig-Holstein) |

President of the Bundestag (1976–1979) Member of the Bundestag (1972-1979) |

1 July 1979 | 30 June 1984 | CDU | Dietrich Stobbe (1979), Hans-Ulrich Klose (1979–1980), Werner Zeyer (1980–1981), Hans Koschnick (1981–1982), Johannes Rau (1982–1983), Franz Josef Strauß (1983–1984) | dissolved the Bundestag in 1982 | |

| 6 |  |

Richard von Weizsäcker (1920–2015) (Berlin, until 1990 West Berlin) |

Governing Mayor of Berlin (1981–1984) | 1 July 1984 | 30 June 1994 | CDU | Franz Josef Strauß (1984), Lothar Späth (1984–1985), Ernst Albrecht (1985–1986), Holger Börner (1986–1987), Walter Wallmann (1987), Bernhard Vogel (1987–1988), Björn Engholm (1988–1989), Walter Momper (1989–1990), Henning Voscherau (1990–1991), Alfred Gomolka (1991–1992), Berndt Seite (1992), Oskar Lafontaine (1992–1993), Klaus Wedemeier (1993–1994) | vetoed one bill | |

| 7 | _(cropped).jpg.webp) |

Roman Herzog (1934–2017) (Baden-Württemberg) |

President of the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany (1987–1994) | 1 July 1994 | 30 June 1999 | CDU | Klaus Wedemeier (1994), Johannes Rau (1994–1995), Edmund Stoiber (1995–1996), Erwin Teufel (1996–1997), Gerhard Schröder (1997–1998), Hans Eichel (1998–1999), Roland Koch (1999) | ||

| 8 |  |

Johannes Rau (1931–2006) (North Rhine-Westphalia) |

President of the Bundesrat (1982–1983 and 1994–1995) Minister President of North Rhine-Westphalia (1978–1998) |

1 July 1999 | 30 June 2004 | SPD | Roland Koch (1999), Kurt Biedenkopf (1999–2000), Kurt Beck (2000–2001), Klaus Wowereit (2001–2002), Wolfgang Böhmer (2002–2003), Dieter Althaus (2003–2004) | ||

| 9 |  |

Horst Köhler (born 1943) (Baden-Württemberg) |

Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund (2000–2004) | 1 July 2004 | 31 May 2010 (resigned) |

CDU | Dieter Althaus (2004), Matthias Platzeck (2004–2005), Peter Harry Carstensen (2005–2006), Harald Ringstorff (2006–2007), Ole von Beust (2007–2008), Peter Müller (2008–2009), Jens Böhrnsen (2009–2010) | vetoed two bills and dissolved the Bundestag in 2005 | |

| 10 |  |

Christian Wulff (born 1959) (Lower Saxony) |

Minister President of Lower Saxony (2003–2010) | 30 June 2010 | 17 February 2012 (resigned) |

CDU | Jens Böhrnsen (2010), Hannelore Kraft (2010–2011), Horst Seehofer (2011–2012) | ||

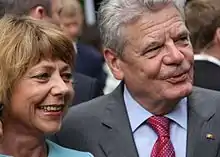

| 11 | _01.jpg.webp) |

Joachim Gauck (born 1940) (Mecklenburg-Vorpommern) |

Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Records (1990–2000) | 18 March 2012 | 18 March 2017 | Independent | Horst Seehofer (2012), Winfried Kretschmann (2012–2013), Stephan Weil (2013–2014), Volker Bouffier (2014–2015), Stanislaw Tillich (2015–2016), Malu Dreyer (2016–2017) | ||

| 12 | .jpg.webp) |

Frank-Walter Steinmeier (born 1956) (Brandenburg) |

Vice Chancellor of Germany (2007–2009) Federal Minister of Foreign Affairs (2005–2009 and 2013–2017) |

19 March 2017 | Incumbent | SPD | Malu Dreyer (2017), Michael Müller (2017–2018), Daniel Günther (2018–2019), Dietmar Woidke (2019–2020), Reiner Haseloff (incumbent until 31 October 2021) | vetoed one bill | |

Living former presidents

In Germany, former presidents are usually referred to as Altbundespräsidenten (presidents emeritus). There are three living former German presidents:

Horst Köhler (age 77)

Horst Köhler (age 77)

since 2010 Christian Wulff (age 61)

Christian Wulff (age 61)

since 2012_by_Sandro_Halank.jpg.webp) Joachim Gauck (age 81)

Joachim Gauck (age 81)

since 2017

See also

- President of Germany (1919–1945)

- Armorial of Presidents of Germany

- Air transports of heads of state and government

- Official state car

References

- "Wie wird der Bundespräsident bezahlt?". www.bundespraesident.de.

- The official title within Germany is Bundespräsident, with der Bundesrepublik Deutschland being added in international correspondence; the official English title is President of the Federal Republic of Germany

Foreign Office of the Federal Republic of Germany (1990). German Institutions. Terminological Series issued by the Foreign Office of the Federal Republic of Germany. Volume 3. de Gruyter. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-89925-584-2. - Court ruling of the German Supreme Court: BVerfG, Urteil des Zweiten Senats vom 10. Juni 2014 - 2 BvE 4/13 - Rn. (1-33) [Link https://www.bundesverfassungsgericht.de/e/es20140610_2bve000413.html], retrieved May 30th, 2019

- "Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany". Gesetze-im-internet.de. Retrieved 2012-11-22.

- German constitutional court: BVerfG, – 2 BvE 4/13–10 June 2014, No. 28

- Website of the President of Germany Retrieved 28 April 2014

- Official website of the President of Germany: Constitutional basis Retrieved 29 April 2014

- Official Website of the President of Germany Retrieved 28 April 2014

- Grundgesetz für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Article 56.

- Haensle, Walter (2009). "Amtseid à la Obama – Verfassungsrechtliche Grundfragen und Probleme des Amtseids nach dem Grundgesetz" (PDF). JURA - Juristische Ausbildung. 31 (9): 670–676. doi:10.1515/JURA.2009.670. ISSN 0170-1452.

- Official Website of the President of Germany: Interaction between constitutional organs. Retrieved 29 April 2014

- Grundgesetz für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland (in German). Article 67.

- Grundgesetz für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland (in German). Articles 67 and 68.

- Grundgesetz für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland (in German). Article 82.

- "Das Amt des Bundespräsidenten und sein Prüfungsrecht | bpb".

- https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/hate-speech-gesetz-das-koennt-ihr-besser-1.5059141

- "Bundespräsidenten: Das achte Nein". Spiegel Online. 2006-12-08.

- The Federal President of Germany – Official Functions. Retrieved 29 April 2014

- http://www.bundespraesident.de/DE/Amt-und-Aufgaben/Wirken-im-Inland/Jubilaeen-und-Ehrenpatenschaften/jubilaeen-und-ehrenpatenschaften-node.html (in German)

- Bryde, in: von Münch/Kunig, GGK III, 5. Aufl. 2003, Rn. 7 zu Art. 81.

- "Das Amt des Bundespräsidenten und sein Prüfungsrecht" (in German). Bpb.de. Retrieved 2012-11-22.

- Heinrich Wilms: Staatsrecht I: Staatsorganisationsrecht unter Berücksichtigung der Föderalismusreform. Stuttgart 2007. pp. 201 ff. (German)

- "Geschäftsordnung des Bundesrates" [Rules of Procedure of the Bundesrat] (PDF). §7 (1). Retrieved 7 November 2016.

Die Vizepräsidenten vertreten den Präsidenten im Falle seiner Verhinderung oder bei vorzeitiger Beendigung seines Amtes nach Maßgabe ihrer Reihenfolge. Ein Fall der Verhinderung liegt auch vor, solange der Präsident des Bundesrates nach Artikel 57 des Grundgesetzes die Befugnisse des Bundespräsidenten wahrnimmt.

- "Bouffier und Tillich vertreten Bundespräsidenten".

- "Interview zum Köhler-Rücktritt: "Das hat es noch nicht gegeben"". tagesschau.de. Retrieved 2012-11-22.

- Official website of the Federal President of Germany Retrieved 29 April 2014

- Zentner, Christian Ed; Bedürftig, Friedemann Ed (1985). Das große Lexikon des Dritten Reiches (in German). München: Südwest Verlag. p. 686. ISBN 978-3-517-00834-9.

- "documentArchiv.de - Gesetz über das Staatsoberhaupt des Deutschen Reichs (01.08.1934)". www.documentarchiv.de.

- Reichgesetzblatt part I. Berlin: de:Bild:RGBL I 1934 S 0747.png. Reich Government. 1 August 1934. p. 747.

- "The Constitution of the German Federation of 11 August 1919". Retrieved 2007-07-16.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bundespräsident (Deutschland). |

- Official website (in English)

- Germany: Heads of State: 1949–2005