Fort Clatsop

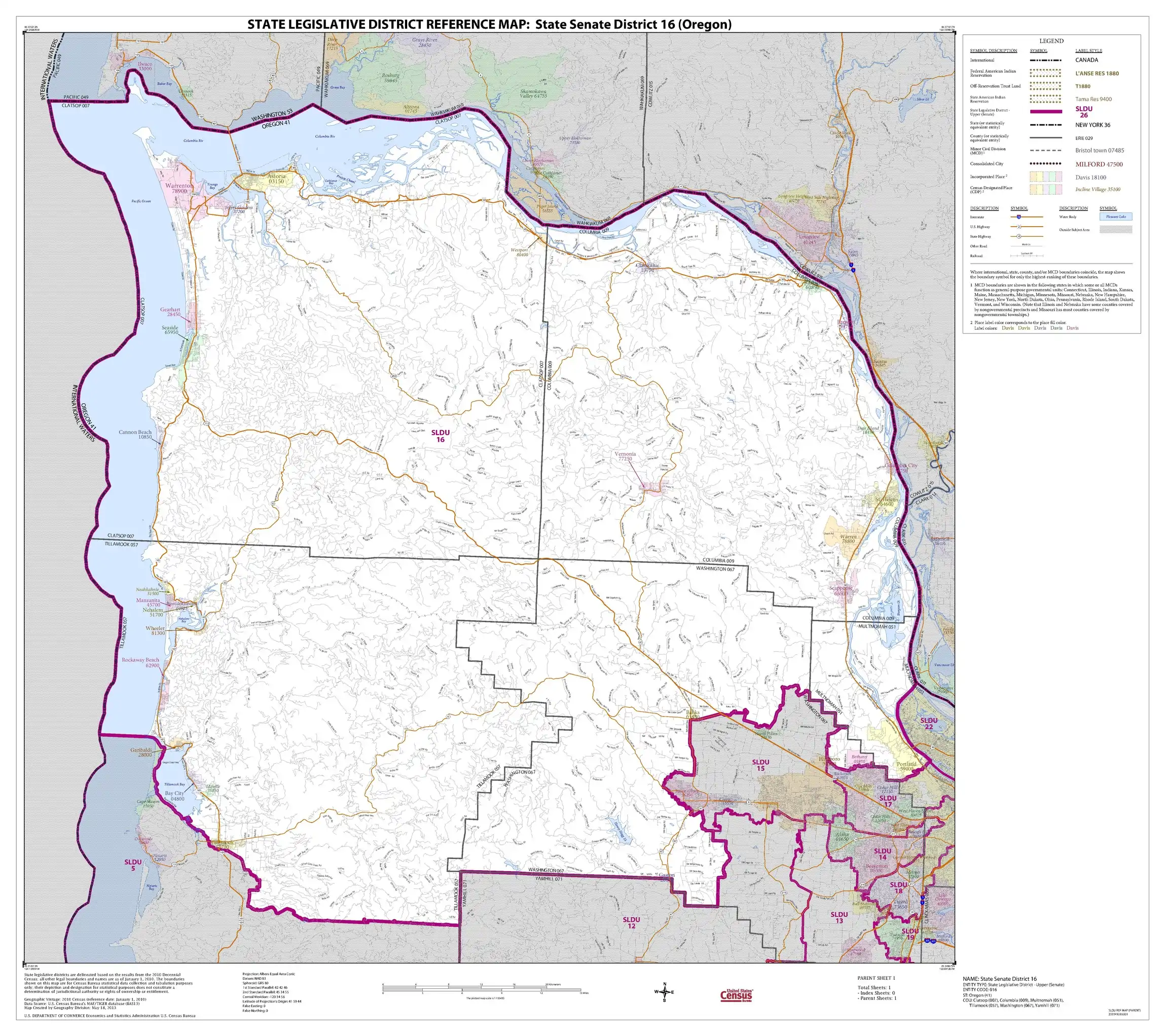

Fort Clatsop was the encampment of the Lewis and Clark Expedition in the Oregon Country near the mouth of the Columbia River during the winter of 1805-1806. Located along the Lewis and Clark River at the north end of the Clatsop Plains approximately 5 miles (8.0 km) southwest of Astoria, the fort was the last encampment of the Corps of Discovery, before embarking on their return trip east to St. Louis.

Fort Clatsop National Memorial | |

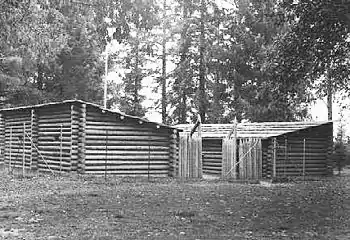

The 2006 replica of Fort Clatsop | |

Near mouth of Columbia River, Oregon  Fort Clatsop (the United States) | |

| Location | Clatsop County, Oregon, USA |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Astoria, Oregon |

| Coordinates | 46°8′1″N 123°52′49″W |

| Area | 125.2 acres (50.7 ha) |

| Built | 1805 |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000640 |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966[1] |

The Fort Clatsop National Memorial located southwest of Astoria.

|

The Lewis and Clark Expedition wintered at Fort Clatsop before returning east to St. Louis in the spring of 1806. It took just over 3 weeks for the Expedition to build the fort, and it served as their camp from December 8, 1805 until their departure on March 23, 1806.[2]

The site is now protected as part of the Lewis and Clark National Historical Park, part of which was formerly known as Fort Clatsop National Memorial until 2004.[3] The original Fort Clatsop decayed in the wet climate of the region but was reconstructed for the sesquicentennial in 1955 from sketches in the journals of William Clark. The replica lasted for fifty years, but was severely damaged by fire in early October 2005, weeks before Fort Clatsop's bicentennial. A new replica, more rustic and rough-hewn, was built by about 700 volunteers in 2006; it opened with a dedication ceremony that took place on December 9. The site is currently operated by the National Park Service.

Background

In 1803, Thomas Jefferson completed the Louisiana Purchase from France. As much of the area had not been explored by whites, Jefferson commissioned an expedition to be led by his secretary, Meriwether Lewis, along with William Clark. Jefferson set a number of goals for the expedition, most notably to determine what the land contained, including plants, animals, and natural resources. Jefferson also wanted to establish good relations with the Native Americans of the area. Additionally, Jefferson was very interested in finding a water route to the Pacific Ocean, which would have cut the travel time from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean considerably.

Locating and building the fort

In late November 1805, after spending a number of days in what is today the state of Washington, Lewis and Clark proposed that the Corps of Discovery move to a location along the Columbia River, based on a recommendation of the local Clatsop Indians.[4] The group decided to vote on the matter, with everyone, including the young Native American female Sacagawea and African American slave York, participating. The group was given three choices: stay on the Washington side of the Columbia River, and be subjected to diets of fish and rainy weather, move upriver, or take the advice of the Clatsop Indians and explore the area to the south of the River. The expedition overwhelmingly decided to take the advice of the local Indians to explore the idea of spending the winter on the southern shore of the River.

Lewis decided to explore the area before moving the entire group. He and five men left to scout the area, leaving Clark and the rest of the group behind.[5] Lewis became frustrated when he could not find the abundant elk that the Clatsop had talked about. In the meantime, Clark had not heard from his companion in a number of days and became increasingly worried. During Lewis' absence, the group performed a number of housekeeping tasks, including fixing their clothes from the wear they had suffered during the long and arduous journey.

Finally, Lewis returned with the news that he had found an adequate location in which to winter. On December 7, 1805, the Corps of Discovery began the short journey to the location chosen by Lewis. Upon arrival, the men split into different groups: Clark led a party to the Pacific Ocean in search of salt, while Lewis split the remaining men into two groups. One group was in charge of hunting, while the other was in charge of cutting down trees to be used in the construction of the fort.[6]

Construction of the fort was slow, due to the incessant precipitation and unyielding wind that made working conditions less than ideal. On December 23, people started to move into the dwelling, even though it didn't yet have a roof. The next day, Christmas Eve, everyone moved in. On Christmas Day it was named "Fort Clatsop" in reference to the local Indian tribe.[4][6]

The structures of Fort Clatsop were relatively simple, consisting of two buildings surrounded by large walls. All of the men lived in one structure, while Lewis, Clark, Sacagawea, her husband Toussaint Charbonneau, and their son, Jean Baptiste, stayed in the other.

Winter activities

The winter of 1805–1806 was very long and rainy, leading to boredom and restlessness for the Corps of Discovery. They passed the time with various activities, including hunting the abundant deer and elk in the region.[7] The deer and elk meat spoiled quickly, but the skins were used to make clothing and moccasins. Realizing the importance of their trip, Lewis spent most of his time at Fort Clatsop documenting the journey, taking notes on the wildlife, terrain, and other features. Lewis also made maps of the area, which would be especially helpful to future settlers of the Pacific Northwest. Finally, Lewis and Clark occasionally traded with the Clatsop Indians, a tribe they had come to dislike, viewing them as untrustworthy and prone to theft.

Ultimately, the group's time along the Columbia River merely served as a place to spend the winter and recoup. The men were suffering from a number of different illnesses and conditions, including venereal diseases and respiratory problems, and felt that departing would make them all feel better.

Departure

Toward the end of the monotonous winter they spent at Fort Clatsop, the men were desperate to return east. Everyone was sick and quite restless, and the steady diet of elk was becoming unbearable. Moreover, even the elk were becoming more difficult to find.[8] Originally, Meriwether Lewis determined the departure date would be April 1, but it was later moved up to March 20. Ultimately, they didn't leave until two days after that due to poor weather.[8]

In order to travel back up the Columbia and reach the mountains, the group was desperately in need of canoes. The Clatsops had a number of them, but refused to trade with Lewis and Clark. Eventually, an agreement was reached for one canoe, but Lewis decided they had no choice but to steal a second one, since they couldn't all travel without at least two boats.

On March 22, the Corps of Discovery began the long journey back to St. Louis. Lewis decided not to send any of the men back with a copy of his notes by sea, as was usually customary, because of the small number of people in the group. Instead, Lewis decided that the group would travel two different routes, in order to see as much of the territory as possible on the way back to St. Louis.

Later use

As a parting gift, Lewis gave Fort Clatsop to Coboway, the chief of the Clatsops.[9] Lewis and Clark had no use for the fort, as they were returning east with no plans to revisit the fort in the near future.[10] Because of the heavy rainfall of the region, the original Fort Clatsop had rotted away by the middle of the 19th century.[11]

The Clatsops used the fort as a useful base for security and other purposes, though they did strip away part of the wood for other uses.[12] The area soon became a very important site for the fur trade in the Pacific Northwest. The location of the fort near the Pacific Ocean and the Columbia River made it a natural site for the fur trade, which expanded rapidly in the years after Lewis and Clark left. Numerous fur trading companies, including the American Fur Company and the Hudson's Bay Company, constructed headquarters in the region.[13]

Since then, there have been two reconstruction efforts. The first, in 1955, lasted for 50 years until a fire destroyed the entire structure in the late evening of October 3, 2005. Federal, state, and community officials immediately pledged to rebuild it. A 9-1-1 operator's insistence that the fire was no more than fog over the nearby Lewis and Clark River delayed firefighters’ arrival by about 15 minutes, possibly impacting their ability to save part of the structure. Investigators found no evidence of arson. The fire started in one of the enlisted men's quarters, where earlier in the day there had been an open hearth fire burning.[14] It took 18 months to build the 1955 reconstruction, much longer than the 3.5 weeks it took to build the original.[15] Shortly after the fire, a second replica was built and finished in 2006. In spite of the loss, the fire renewed archaeological interest in the site, as excavations had not been possible while the replica was standing. Additionally, the new replica was built utilizing information on the original fort that was not available for the 1955 replica. The 2006 replica also features a fire detection system.

The replica of the fort isn't in the exact location of the original, as no remains of the original fort have been found. However, it is thought to be quite close to the exact location.[16]

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- Ambrose, Stephen E. (1997). Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West (1st Touchstone ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 326. ISBN 0684826976.

- "Lewis and Clark National Historical Park Designation Act, P.L. 108–387". uscode.house.gov. October 30, 2004. Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- Fritz, Harry William (2004). The Lewis and Clark Expedition. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood. pp. 46–47. ISBN 0313316619.

- Nicandri, David L. (2010). River of Promise.; Lewis and Clark on the Columbia. Lewis. p. 232. ISBN 0982559712.

- Ambrose (1997), pp. 318.

- Nicandri (2010), p. 235.

- Ambrose (1997), pp. 333-334.

- Nicandri (2010), p. 244.

- Ambrose (1997), p. 336.

- Fort Clatsop National Park Service Accessed 9 November 2014.

- "Fort Clatsop Site, 1900".

- "Euro-American Adaptation and Importation: 1800–1850: Early Exploration and Fur-Trading Outposts".

- Komo News Dispatcher Tells 911 Caller Fort Clatsop Fire Was Just Fog Accessed 21 July 2016.

- The Seattle Times No signs of arson in Fort Clatsop fire. Accessed 9 November 2014.

- "Fort Clatsop".

Further reading

- Frederick L. Brown (Winter 2006). "Imagining Fort Clatsop". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 107 (4). Archived from the original on 2008-12-07.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fort Clatsop. |

- Lewis and Clark National Historical Park - National Park Service

- History of Fort Clatsop - National Park Service

- Fort Clatsop & N. Oregon coast - The Seattle Times - Travel - 05-April-2007

- The Lewis & Clark Expedition: Documenting the Uncharted Northwest Name, a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- "Fort Clatsop National Memorial". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. 28 November 1980. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

- Cannon-Miller, Kelly. "Fort Clatsop". The Oregon Encyclopedia.

- Ambrose, 1996, Chap. VI

- Lavender, 2001 pp.30–31

- DeVoto, 1997 p.xxix

- Lavender, 2001

- See: Lewis and Clark Expedition for detailed citations