Salishan languages

The Salishan (also Salish) languages are a group of languages of the Pacific Northwest in North America (the Canadian province of British Columbia and the American states of Washington, Oregon, Idaho and Montana).[1] They are characterised by agglutinativity and syllabic consonants. For instance the Nuxalk word clhp’xwlhtlhplhhskwts’ (IPA: [xɬpʼχʷɬtʰɬpʰɬːskʷʰt͡sʼ]), meaning "he had had [in his possession] a bunchberry plant", has thirteen obstruent consonants in a row with no phonetic or phonemic vowels. The Salishan languages are a geographically contiguous block, with the exception of the Nuxalk (Bella Coola), in the Central Coast of British Columbia, and the extinct Tillamook language, to the south on the central coast of Oregon.

| Salishan | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Pacific Northwest and Interior Plateau/Columbia Plateau in Canada and the United States |

| Linguistic classification | One of the world's primary language families |

| Subdivisions | |

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | sal |

| Glottolog | sali1255 |

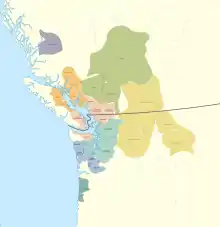

Pre-contact distribution of Salishan languages (in red). | |

The terms Salish and Salishan are used interchangeably by linguists and anthropologists studying Salishan, but this is confusing in regular English usage. The name Salish or Selisch is the endonym of the Flathead Nation. Linguists later applied the name Salish to related languages in the Pacific Northwest. Many of the peoples do not have self-designations (autonyms) in their languages; they frequently have specific names for local dialects, as the local group was more important culturally than larger tribal relations.

All Salishan languages are considered critically endangered, some extremely so, with only three or four speakers left. Those languages considered extinct are often referred to as 'sleeping languages,' in that no speakers exist currently. In the early 21st century, few Salish languages have more than 2,000 speakers. Fluent, daily speakers of almost all Salishan languages are generally over sixty years of age; many languages have only speakers over eighty. Salishan languages are most commonly written using the Americanist phonetic notation to account for the various vowels and consonants that do not exist in most modern alphabets. Many groups have evolved their own distinctive uses of the Latin alphabet, however, such as the St'at'imc.

Family division

The Salishan language family consists of twenty-three languages. Below is a list of Salishan languages, dialects, and subdialects. The genetic unity among the Salish languages is evident. Neighboring groups have communicated often, to the point that it is difficult to untangle the influence each dialect and language has upon others.

A 1969 study found that "language relationships are highest and closest among the Interior Division, whereas they are most distant among the Coast Division."[2]

This list is a linguistic classification that may not correspond to political divisions. In contrast to classifications made by linguistic scholars, many Salishan groups consider their particular variety of speech to be a separate language rather than a dialect.

Extinct languages or dialects are marked with (†) at the highest level.

Bella Coola

- 1. Bella Coola (AKA Nuxalk, Salmon River)

Coast Salish

- A. Central Coast Salish (AKA Central Salish)

- 2. Comox

- K'omoks (Sahtloot) (AKA Qʼómox̣ʷs)

- Tla A'min (Homalco/Xwemalhkwu–Klahoose–Sliammon/Tla A-min) (AKA ʔayʔaǰuθəm)

- 3. Halkomelem

- Island (AKA Hulʼq̱ʼumiʼnumʼ, Həl̕q̓əmín̓əm̓)

- Downriver (AKA Hunqʼumʔiʔnumʔ)

- Upriver (AKA Upper Sto:lō, Halqʼəméyləm)

- Sts'Ailes

- Chilliwack area bands

- Tait

- Skway

- 4. Lushootseed (AKA Puget Salish, Skagit-Nisqually, dxʷləšúcid) (†)

- Northern

- Skagit (AKA Skaǰət)

- Sauk-Suiattle (AKA ̌sa̓ʔqʷəbixʷ

- Snohomish (AKA Sduhubš)

- Southern

- Duwamish-Suquamish (AKA Dxʷduʔabš)

- Puyallup (AKA Spuyaləpubš)

- Nisqually (AKA Sqʷaliʔabš)

- Northern

- 5. Nooksack (AKA Łə́čələsəm, Łə́čælosəm) (†)

- 6. Pentlatch (AKA Pənƛ̕áč) (†)

- 7. Sechelt (AKA Seshelt, Sháshíshálh, Shashishalhem, Šášíšáɬəm)

- 8. Squamish (AKA Sḵwx̱wú7mesh snichim, Sḵwx̱wú7mesh, Sqwxwu7mish, Sqʷx̣ʷúʔməš)

- i. Straits Salish group (AKA Straits)

- 9. Klallam (AKA Clallam, Nəxʷsƛ̕áy̓emúcən) (†)

- Becher Bay

- Eastern

- Western

- 10. Northern Straits (AKA Straits)

- 9. Klallam (AKA Clallam, Nəxʷsƛ̕áy̓emúcən) (†)

- 11. Twana (AKA Skokomish, Sqʷuqʷúʔbəšq, Tuwáduqutšad) (†)

- 2. Comox

- B. Tsamosan (AKA Olympic) (†)

- i. Inland

- 12. Cowlitz (AKA Lower Cowlitz, Sƛ̕púlmš) (†)

- 13. Upper Chehalis (AKA Q̉ʷay̓áyiɬq̉) (†)

- Oakville Chehalis

- Satsop

- Tenino Chehalis

- ii. Maritime

- 14. Lower Chehalis (AKA Łəw̓ál̕məš) (†)

- Humptulips

- Westport-Shoalwater

- Wynoochee

- 15. Quinault (AKA Kʷínayɬ) (†)

- 14. Lower Chehalis (AKA Łəw̓ál̕məš) (†)

- i. Inland

Interior Salish

- A. Northern

- 17. Shuswap (AKA Secwepemctsín, səxwəpməxcín)

- Eastern

- Kinbasket

- Shuswap Lake

- Western

- Canim Lake

- Chu Chua

- Deadman's Creek–Kamloops

- Fraser River

- Pavilion-Bonaparte

- Eastern

- 18. Lillooet (AKA Lilloet, St'át'imcets)

- Lillooet-Fountain

- Mount Currie–Douglas

- 19. Thompson River Salish (AKA Nlakaʼpamux, Ntlakapmuk, nɬeʔkepmxcín, Thompson River, Thompson Salish, Thompson, known in frontier times as the Hakamaugh, Klackarpun, Couteau or Knife Indians)

- Lytton

- Nicola Valley

- Spuzzum–Boston Bar

- Thompson Canyon

- 17. Shuswap (AKA Secwepemctsín, səxwəpməxcín)

- B. Southern

- 20. Coeur d’Alene (AKA Snchitsuʼumshtsn, snčícuʔumšcn)

- 21. Columbia-Moses (AKA Columbia, Nxaʔamxcín)

- Chelan

- Entiat

- Columbian

- Wenatchee (AKA Pesquous)

- 22. Colville-Okanagan (AKA Okanagan, Nsilxcín, Nsíylxcən, ta nukunaqínxcən)

- Northern

- Quilchena & Spaxomin

- Arrow Lakes

- Penticton

- Similkameen

- Vernon

- Southern

- Colville-Inchelium

- Methow

- San Poil–Nespelem

- Southern Okanogan

- Northern

- 23. Montana Salish (Kalispel–Pend d'Oreille language, Spokane–Kalispel–Bitterroot Salish–Upper Pend d'Oreille)

Pentlatch, Nooksack, Twana, Lower Chehalis, Upper Chehalis, Cowlitz, Klallam, and Tillamook are now extinct. Additionally, the Lummi, Semiahmoo, Songhees, and Sooke dialects of Northern Straits are also extinct.

Genetic relations

No relationship to any other language family is well established.

Edward Sapir suggested that the Salishan languages might be related to the Wakashan and Chimakuan languages in a hypothetical Mosan family. This proposal persists primarily through Sapir's stature: with little evidence for such a family, no progress has been made in reconstructing it.[3]

The Salishan languages, principally Chehalis, contributed greatly to the vocabulary of the Chinook Jargon.

Family features

- post-velar harmony (more areal)

- presence of syllables without vowels

- grammatical reduplication

- nonconcatenation (infixes, metathesis, glottalization)

- tenselessness

- nounlessness (controversial)

Syntax

The syntax of Salish languages is notable for its word order (verb-initial), its valency-marking, and the use of several forms of negation.

Salish languages are verb-initial

Although there is a wide array of Salish languages, they all share some basic traits. All are verb initial languages, with VSO (verb-subject-object) being the most common word order. Some Salishan languages allow for VOS and SVO as well. There is no case marking, but central noun phrases will often be preceded by determiners while non-central NPs will take prepositions. Some Salishan languages are ergative, or split-ergative, and many take unique object agreement forms in passive statements. In the St'át'imcets (Lillooet Salish) language, for example, absolutive relative clauses (including a head, like "the beans," and a restricting clause, like "that she re-fried," which references the head) omit person markers, while ergative relative clauses keep person makers on the subject, and sometimes use the topic morpheme "-tali." Thus, St'át'imcets is split-ergative, as it is not ergative all the time.[4] Subject and object pronouns usually take the form of affixes that attach to the verb. All Salish languages are head-marking. Possession is marked on the possessed noun phrase as either a prefix or a suffix, while person is marked on predicates. In Central Salish languages like Tillamook and Shuswap, only one plain NP is permitted aside from the subject.

Salish languages have extensive valency-marking

Salishan languages are known for their polysynthetic nature. A verb stem will often have at least one affix, which is typically a suffix. These suffixes perform a variety of functions, such as transitive, causative, reciprocal, reflexive, and applicative. Applicative affixes seem to be present on the verb when the direct object is central to the event being discussed, but is not the theme of the sentence. The direct object may be a recipient, for example. It may also refer to a related noun phrase, like the goal a verb intends to achieve, or the instrument used in carrying out the action of the verb. In the sentence ‘The man used the axe to chop the log with.’, the axe is the instrument and is indicated in Salish through an applicative affix on the verb.

Applicative affixes increase the number of affixes a verb can take on, that is, its syntactic valence. They are also known as "transitivizers" because they can change a verb from intransitive to transitive. For example, in the sentence 'I got scared.', 'scared' is intransitive. However, with the addition of an applicative affix, which is syntactically transitive, the verb in Salish becomes transitive and the sentence can come to mean ‘I got scared of you.’. In some Salishan languages, such as Sḵwx̲wú7mesh, the transitive forms of verbs are morphologically distinctive and marked with a suffix, while the intransitive forms are not.[5] In others such as Halkomelem, intransitive forms have a suffix as well. In some Salish languages, transitivizers can be either controlled (the subject conducted the action on purpose) or limited-control (the subject did not intend to conduct the action, or only managed to conduct a difficult action).[6]

These transitivizers can be followed by object suffixes, which come to modern Salishan languages via Proto-Salish. Proto-Salish had two types of object suffixes, neutral (regular transitive) and causative (when a verb causes the object to do something or be in a certain state), that were then divided into first, second, and third persons, and either singular or plural. Tentative reconstructions of these suffixes include the neutral singular *-c (1st person), *-ci (2nd person), and *-∅ (3rd person), the causative singular *-mx (1st), *-mi (2nd), and *-∅ (3rd), the neutral plural *-al or *-muɬ (1st), *-ulm or *-muɬ (2nd), and the causative plural *-muɬ (1st and 2nd). In Salishan languages spoken since Proto-Salish, the forms of those suffixes have been subject to vowel shifts, borrowing pronoun forms from other languages (such as Kutenai), and merging of neutral and causative forms (as in Secwepemc, Nlaka'pamuctsin, Twana, Straits Salishan languages, and Halkomelem).[7]

Salish languages have three patterns of negation

There are three general patterns of negation among the Salishan languages. The most common pattern involves a negative predicate in the form of an impersonal and intransitive stative verb, which occurs in sentence initial position. The second pattern involves a sentence initial negative particle that is often attached to the sentence's subject, and the last pattern simply involves a sentence initial negative particle without any change in inflectional morphology or a determiner/complementizer. In addition, there is a fourth restricted pattern that has been noted only in Squamish.

Nounlessness

Salishan languages (along with the Wakashan and the extinct Chimakuan languages) exhibit predicate/argument flexibility. All content words are able to occur as the head of the predicate (including words with typically 'noun-like' meanings that refer to entities) or in an argument (including those with 'verb-like' meanings that refer to events). Words with noun-like meanings are automatically equivalent to [be + NOUN] when used predicatively, such as Lushootseed sbiaw which means '(is a) coyote'. Words with more verb-like meanings, when used as arguments, are equivalent to [one that VERBs] or [VERB+er]. For example, Lushootseed ʔux̌ʷ means '(one that) goes'.

The following examples are from Lushootseed.

| Sentence (1a) | ʔux̌ʷ ti sbiaw | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Morphemes | ʔux̌ʷ | ti | sbiaw |

| Gloss | go | SPEC | coyote |

| Kinkade interpretation | goes | that which | is a coyote |

| Syntax | Predicate | Subject | |

| Translation | The/a coyote goes. | ||

| Sentence (1b) | sbiaw ti ʔux̌ʷ | ||

| Morphemes | sbiaw | ti | ʔux̌ʷ |

| Gloss | coyote | SPEC | go |

| Kinkade interpretation | is a coyote | that which | goes |

| Syntax | Predicate | Subject | |

| Translation | The one who goes is a coyote. | ||

An almost identical pair of sentences from St’át’imcets demonstrates that this phenomenon is not restricted to Lushootseed.

| Sentence (2a) | t’ak tink’yápa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morphemes | t’ak | ti- | nk’yap | -a |

| Gloss | go.along | DET- | coyote | -DET |

| Kinkade interpretation | goes along | that which | is a coyote | |

| Syntax | Predicate | Subject | ||

| Translation | The/a coyote goes along. | |||

| Sentence (2b) | nk’yap tit’áka | |||

| Morphemes | nk’yap | ti- | t’ak | -a |

| Gloss | coyote | DET- | go.along | -DET |

| Kinkade interpretation | is a coyote | that which | goes along | |

| Syntax | Predicate | Subject | ||

| Translation | The one going along is a coyote. | |||

This and similar behaviour in other Salish and Wakashan languages has been used as evidence for a complete lack of a lexical distinction between nouns and verbs in these families. This has become controversial in recent years. David Beck of the University of Alberta contends that there is evidence for distinct lexical categories of 'noun' and 'verb' by arguing that, although any distinction is neutralised in predicative positions, words that can be categorised as 'verbs' are marked when used in syntactic argument positions. He argues that Salishan languages are omnipredicative, but only have 'uni-directional flexibility' (not 'bi-directional flexibility'), which makes Salishan languages no different from other omnipredicative languages such as Arabic and Nahuatl, which have a clear lexical noun-verb distinction.

Beck does concede, however, that the Lushootseed argument ti ʔux̌ʷ ('the one who goes', shown in example sentence (1b) above) does represent an example of an unmarked 'verb' used as an argument and that further research may potentially substantiate M. Dale Kinkade's 1983 position that all Salishan content words are essentially 'verbs' (such as ʔux̌ʷ 'goes' and sbiaw 'is a coyote') and that the use of any content word as an argument involves an underlying relative clause. For example, with the determiner ti translated as 'that which', the arguments ti ʔux̌ʷ and ti sbiaw would be most literally translated as 'that which goes' and 'that which is a coyote' respectively.[8][9][10]

Historical linguistics

There are twenty-three languages in the Salishan language family. They occupy the Pacific Northwest, with all but two of them being concentrated together in a single large area. It is clear that these languages are related, but it's difficult to track the development of each because their histories are so interwoven. The different speech communities have interacted a great deal, making it nearly impossible to decipher the influences of varying dialects and languages on one another. However, there are several trends and patterns that can be historically traced to generalize the development of the Salishan languages over the years.

The variation between the Salishan languages seems to depend on two main factors: the distance between speech communities and the geographic barriers between them. The diversity between the languages corresponds directly to the distance between them. Closer proximity often entails more contact between speakers, and more linguistics similarities are the result. Geographic barriers like mountains impede contact, so two communities that are relatively close together may still vary considerably in their language use if there is a mountain dividing them.

The rate of change between neighboring Salishan languages often depends on their environments. If for some reason two communities diverge, their adaptation to a new environment can separate them linguistically from each other. The need to create names for tools, animals, and plants creates an array of new vocabulary that divides speech communities. However, these new names may come from borrowing from neighboring languages, in which case two languages or dialects can grow more alike rather than apart. Interactions with outside influences through trade and intermarriage often result in language change as well.

Some cultural elements are more resilient to language change, namely, religion and folklore. Salishan language communities that have demonstrated change in technology and environmental vocabulary have often remained more consistent with their religious terminology. Religion and heavily ingrained cultural traditions are often regarded as sacred, and so are less likely to undergo any sort of change. Indeed, cognate lists between various Salishan languages show more similarities in religious terminology than they do in technology and environment vocabulary. Other categories with noticeable similarities include words for body parts, colors, and numbers. There would be little need to change such vocabulary, so it's more likely to remain the same despite other changes between languages. The Coast Salishan languages are less similar to each other than are the Interior Salishan languages, probably because the Coast communities have more access to outside influences.

Another example of language change in the Salishan language family is word taboo, which is a cultural expression of the belief in the power of words. Among the Coast languages, a person's name becomes a taboo word immediately following their death. This taboo is lifted when the name of the deceased is given to a new member of his/her lineage. In the meantime, the deceased person's name and words that are phonetically similar to the name are considered taboo and can only be expressed via descriptive phrases. In some cases these taboo words are permanently replaced by their chosen descriptive phrases, resulting in language change.

Pragmatics

At least one Salish language, Lillooet Salish, differs from Indo-European languages in terms of pragmatics. Lillooet Salish does not allow presuppositions about a hearer's beliefs or knowledge during a conversation.[11][12][13] To demonstrate, it's useful to compare Lillooet Salish determiners with English determiners. English determiners take the form of the articles ‘a’, ‘an’ and ‘the’. The indefinite articles ‘a’ and ‘an’ refer to an object that is unfamiliar or that has not been previously referenced in conversation. The definite article ‘the’ refers to a familiar object about which both the speaker and the listener share a common understanding. Lillooet Salish and several other Salish languages use the same determiner to refer to both familiar and unfamiliar objects in conversation. For example, when discussing a woman, Lillooet Salish speakers used [ɬəsɬánay] (with [ɬə] serving as the determiner and [sɬánay] meaning ‘woman’) to refer to the woman both when initially introducing her and again when referencing her later on in the conversation. Thus, no distinction is made between a unique object and a familiar one.

This absence of varying determiners is a manifestation of the lack of presuppositions about a listener in Salish. Using a definite article would presuppose a mental state of the listener: familiarity with the object in question. Similarly, a Salishan language equivalent of the English sentence "It was John who called" would not require the assumption that the listener knows that someone called. In English, such a sentence implies that someone called and serves to clarify who the caller was. In Salish, the sentence would be void of any implication regarding the listener's knowledge. Rather, only the speaker's knowledge about previous events is expressed.

The absence of presuppositions extends even to elements that seem to inherently trigger some kind of implication, such as ‘again’, ‘more’, ‘stop’, and ‘also’. For example, in English, beginning a conversation with a sentence like "It also rained yesterday" would probably be met with confusion from the listener. The word ‘also’ signifies an addition to some previously discussed topic about which both the speaker and the listener are aware. However, in Salish, a statement like "It also rained yesterday" is not met with the same kind of bewilderment. The listener's prior knowledge (or lack thereof) is not conventionally regarded by either party in a conversation. Only the speaker's knowledge is relevant.

The use of pronouns illustrates the disregard for presuppositions as well. For example, a sentence like "She walked there, and then Brenda left" would be acceptable on its own in Lillooet Salish. The pronoun ‘she’ can refer to Brenda and be used without the introduction that would be necessary in English. It is key to note that presuppositions do exist in Salishan languages; they simply don't have to be shared between the speaker and listener the way they do in English and other Indo-European languages. The above examples demonstrate that presuppositions are present, but the fact that the listener doesn't necessarily have to be aware of them signifies that the presuppositions only matter to the speaker. They are indicative of prior information that the speaker alone may be aware of, and his/her speech reflects merely his/her perspective on a situation without taking into account the listener's knowledge. Although English values a common ground between a listener and speaker and thus requires that some presuppositions about another person's knowledge be made, Salish does not share this pragmatic convention.

In popular culture

Stanley Evans has written a series of crime fiction novels that use Salish lore and language.

An episode of Stargate SG-1 ("Spirits", 2x13) features a culture of extraterrestrial humans loosely inspired by Pacific coastal First Nations culture, and who speak a language referred to as "ancient Salish".

In the video game Life Is Strange, the Salish lore was used on certain history of Arcadia Bay as totem poles are seen on some areas. Including a segment from the first episode of its prequel involving the raven.

References

- "First Nations Culture Areas Index". the Canadian Museum of Civilization.

- Jorgensen, Joseph G. (1969). Salishan language and culture. Language Science Monographs. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University. p. 105.

- Beck (2000).

- Roberts, Taylor (July 1999). "Grammatical Relations and Ergativity in St'át'imcets (Lillooet Salish)". International Journal of American Linguistics. 65 (3): 275–302. doi:10.1086/466391. JSTOR 1265788. S2CID 143415352. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- Kuipers, Aert H. (1968). "The categories verb-noun and transitive-intransitive in English and Squamish". Lingua. 21: 610–626. doi:10.1016/0024-3841(68)90080-6. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- Jacobs, Peter William (2011). Control in Skwxwú7mesh. Vancouver: University of British Columbia. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- Newman, Stanley (Oct 1979). "The Salish Object Forms". International Journal of American Linguistics. 45 (4): 299–308. doi:10.1086/465612. JSTOR 1264720. S2CID 143874319. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- Beck, David. Unidirectional flexibility and the noun-verb distinction in Lushootseed (PDF). Retrieved 2013-11-20.

- Cable, Seth. Lexical Categories in the Salish and Wakashan Languages (PDF). Retrieved 2013-11-20.

- Kinkade, M. Dale. 'Salishan evidence the universality of "noun" and "verb"', Lingua 60.

- Matthewson, Lisa (2006). Presuppositions and Cross-Linguistic Variation (PDF). Proceedings of the North East Linguistics Society 36. Amherst, MA. Retrieved 2015-10-18.

- Matthewson, Lisa (1996). Determiner systems and quantificational strategies: evidence from Salish. University of British Columbia. Retrieved 2015-10-18.

- Matthewson, Lisa (2008). Pronouns, Presuppositions, and Semantic Variation. Proceedings of SALT XVIII. Retrieved 2015-10-18.

Bibliography

- Beck, David. (2000). Grammatical Convergence and the Genesis of Diversity in the Northwest Coast Sprachbund. Anthropological Linguistics 42, 147–213.

- Boas, Franz, et al. (1917). Folk-Tales of Salishan and Sahaptin Tribes. Memoirs of the American Folk-Lore Society, 11. Lancaster, Pa: American Folk-Lore Society.

- Czaykowska-Higgins, Ewa; & Kinkade, M. Dale (Eds.). (1997). Salish Languages and Linguistics: Theoretical and Descriptive Perspectives. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-015492-7.

- Davis, Henry. (2005). On the Syntax and Semantics of Negation in Salish. International Journal of American Linguistics 71.1, January 2005.

- Davis, Henry. and Matthewson, Lisa. (2009). Issues in Salish Syntax and Semantics. Language and Linguistics Compass, 3: 1097–1166. Online.

- Flathead Culture Committee. (1981). Common Names of the Flathead Language. St. Ignatius, Mont: The Committee.

- Jorgensen, Joseph G. (1969). Salish Language and Culture. 3. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Publications.

- Kiyosawa, Kaoru; Donna B. Gerdts. (2010). Salish Applicatives. Leiden, Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV.

- Kroeber, Paul D. (1999). The Salish Language Family: Reconstructing Syntax. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press in cooperation with the American Indian Studies Research Institute, Indiana University, Bloomington.

- Kuipers, Aert H. (2002). Salish Etymological Dictionary. Missoula, MT: Linguistics Laboratory, University of Montana. ISBN 1-879763-16-8

- Liedtke, Stefan. (1995). Wakashan, Salishan and Penutian and Wider Connections Cognate Sets. Linguistic Data on Diskette Series, no. 09. Munchen: Lincom Europa.

- Pilling, James Constantine. (1893). Bibliography of the Salishan Languages. Washington: G.P.O.

- Pilling, James Constantine (2007). Bibliography of the Salishan Languages. Reprint by Gardners Books. ISBN 978-1-4304-6927-8

- Silver, Shirley; Wick R. Miller. (1997). American Indian languages: Cultural and Social Contexts. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Hamill, Chad (2012). Songs of power and prayer in the Columbia Plateau: the Jesuit, the medicine man, and the Indian hymn singer. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press. ISBN 978-0-87071-675-1. Archived from the original on 2015-09-25. Salishan language hymns.

- Thompson, Laurence C. (1973). The Northwest. In T. A. Sebeok (Ed.), Linguistics in North America (pp. 979–1045). Current Trends in Linguistics (Vol. 10). The Hague: Mouton.

- Thompson, Laurence C. (1979). Salishan and the Northwest. In L. Campbell & M. Mithun (Eds.), The Languages of Native America: Historical and Comparative Assessment (pp. 692–765). Austin: University of Texas Press.

External links

| Look up Salish in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wiktionary has a list of reconstructed forms at Appendix:Proto-Salishan reconstructions |

- Bibliography of Materials on Salishan Languages (YDLI)

- University of Montana Occasional Papers in Linguistics (UMOPL) (Native languages of the Northwest)

- Coast Salish Culture: an Outline Bibliography

- Coast Salish Collections

- International Conference on Salish and Neighboring Languages

- The Salishan Studies List (Linguist List)

- Native Peoples, Plants & Animals: Halkomelem

- Saanich (Timothy Montler's site)

- Klallam (Timothy Montler's site)

- A Bibliography of Northwest Coast Linguistics

- Classification of the Salishan languages reflecting current scholarship

- Nkwusm Salish Language Institute

- Tulalip Lushootseed Language Web Site

- Recordings of Montana Salish Wordlists with phonetic transcription by Peter Ladefoged