Anglo-Manipur War

The Anglo-Manipur War was an armed conflict between the British Empire and the Kingdom of Manipur. The war lasted between 31 March and 27 April 1891, ending in a British victory.

| Anglo-Manipur War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The sculptures of two dragons situated in front of the Kangla Palace, which were destroyed during the war. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

+395 2 guns[3][4] |

+3,200 2 guns[3][4] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

4 † 15 (WIA)[3][4] |

+178 † 5 | ||||||

Background

In the First Anglo-Burmese War, the British helped prince Gambhir Singh regain his kingdom of Manipur, which had been heretofore occupied by the Burmese.[2] Subsequently, Manipur became a British protectorate.[5] From 1835, the British stationed a Political Agent in Manipur.[6]

In 1890, the reigning Maharaja was Surachandra Singh. His brother[lower-alpha 1] Kulachandra Singh was the jubraj (heir apparent)[lower-alpha 2] and another brother Tikendrajit Singh was the military commander (senapati). Frank Grimwood was the British Politcal Agent.[8]

Tikendrajit is said to have been the most able of the three brothers, who was also friendly with the Political Agent.[8] According to historian Katherine Prior, the British influence depended on the military aid they had provided to the ruling family, which had dried up in the 1880s, leading Tikendrajit to doubt the value of British alliance.[8]

Coup and rebellion

On 21 September 1890, Tikendrajit Singh led a palace coup, ousting Maharaja Surachandra Singh and installing Kulachandra Singh as the ruler. He also pronounced himself as the new jubraj.[6][8][lower-alpha 3] Surachandra Singh took refuge in British residency, where Grimwood assisted him to flee the state.[6] The Maharaja had given the impression that he was abdicating the throne but, after reaching the British territory in the neighbouring Assam Province, he recanted and wanted return to the state. Both the Political Agent and the Chief Commissioner of Assam, James Wallace Quinton, dissuaded from returning.[10]

Surachandra Singh reached Calcutta and appealed to the Government of India, reminding the British of the services he had rendered.[8][10] On 24 January 1891, the Governor-General instructed the Chief Commissioner of Assam to settle the matter by going to Manipur:

The Governor-General in Council thinks that you should visit Manipur, for the avowed purpose of making, and, if necessary, enforcing, a decision on the merits of the case. You should probably have with you a sufficient force to overcome the conspirators. It is probable that a very small body of troops would be enough, and that suffcient numbers could be taken from Cachar or Kohima.[11]

The Chief Commissioner Quinton persuaded the Government in Calcutta that there would be no use trying to reinstate the Maharaja. This was agreed, but the Government wanted the Senapati Tikendrajit Singh disciplined.[12]

Quinton arrived in Manipur on 22 March 1891, with an escort of 400 Gurkhas under the command of Colonel Skene. The plan was to hold a Darbar in the residency with the erstwhile jubraj Kulachandra Singh (now regarded as the Regent) attending along with all the nobles, where a demand would be made to surrender the senapati. The Regent came to attend the Darbar, but the senapati did not. Another attempt was made the next day which was also unsuccessful.[13] Quinton ordered the arrest of senapati in his own fort, which was evidently repulsed and the residency itself was beseiged. Finally Quinton went on to negotiate with Tikendrajit, accompanied by Grimwood, Skene and other British officers. The talks failed and while returning, the British party was attacked by an "angry crowd". Grimwood was speared to death. The others escaped to the fort. But during the night the crowd led them out and executed them, Quinton included.[8][lower-alpha 4]

According to later accounts, Quinton had proposed to Kulachandra Singh a cessation of all hostilities and his return to Kohima (in Naga Hills to the north of Manipur). Kulachandra and Tikendrajit regarded the proposals as deception.[6][1]

The surviving British troops beseiged in the residency were led out by two junior officers in the dead of night, along with Frank Grimwood's wife Ethel Grimwood. It was a disorganised retreat. But they were met in the forests by a relief party arriving from Cachar and were rescued. The Residency was set on fire soon after their departure.[6][14][15]

On 27 March 1891, news of the executions reached the British. Colonel Charles James William Grant took the initiative organising a punitive expedition consisting of 50 soldiers of the 12th (Burma) Madras Infantry and 35 members of the 43rd Gurkha Regiment, Grant's column left Tamu, Burma the following day.[4]

The only woman in the retreat from the residency was Ethel Grimwood, who was later lionised as a heroine of the "Manipur Disaster" when she returned to Britain. She received a medal, £1,000, a civil list pension and she wrote her biography. It is unclear now as to her contribution, but a hero was required and Ethel became that hero.[6]

War

On 31 March 1891, British India declared war on Kangleipak, expeditionary forces were assembled in Kohima and Silchar. On the same day, the Tamu column seized Thoubal after ousting an 800-man Manipuri garrison. On 1 April, 2,000 Manipuri soldiers accompanied by two guns laid siege to the village, Grant's troops repelled numerous attacks during the course of nine days. On 9 April, the Tamu column retreated from Thoubal in order to join the other columns, after being reinforced by 100 rifles of the 12th (Burma) Madras Infantry. Kangleipak forces suffered heavy casualties during the engagement while the British lost one soldier dead and four wounded.[3][16]

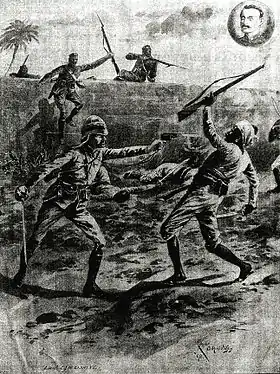

The Kohima column was launched on 20 April, encountering no resistance apart from coming under rifle fire four days later. On 21 April, the Silchar column reached Thoubal, the next day the Tamu column clashed with Meitei troops outside Palel, after the later pursued the British troops, the Meitei were once more pushed back. On 25 April, British scouts encountered 400 Manipuri soldiers on the Khongjom hillock in the vicinity of Palel. 350 infantrymen, 44 cavalry and 2 guns mounted an assault on the remainder of the Kangleipak army. Hand-to-hand fighting ensued, 2 British soldiers were killed and 11 were severely injured, while the Manipuri lost over 128 men.[3][4][17]

On 27 April 1891, the Silchar, Tamu and Kohima columns united, capturing Imphal after finding it deserted, the Union Jack was hoisted above the Kangla Palace, 62 native loyalists were freed by the British troops. On 23 May 1891, Tikendrajit Singh was detained by British authorities On 13 August 1891, five Manipuri commanders including Tikendrajit were hanged for waging war against the British Empire, Kulachandra Singh along with 21 Kangleipak noblemen received sentences of property forfeiture and lifetime exile. Manipur underwent a disarmament campaign, 4,000 firearms were confiscated from the local population.[1][3][4][18]

On 22 September 1891, the British placed the young boy Meidingngu Churachand on the throne.[16]

Legacy

Ethel Grimwood was given £1,000, a pension and the Royal Red Cross (despite having no links to nursing).[6] British participants of the Manipuri expedition received the North East Frontier clasp for the India General Service Medal. Colonel Charles James William Grant also received the Victoria Cross, for his actions during the battle of Thoubal.[16][19]

13 August is commemorated yearly as "Patriots Day" by the Manipuri population, with remarks to honour the Kangeilpak soldiers that lost their lives during the war. Tikendrajit Singh's portrait is included in the National Portrait Gallery inside the House of the People in New Delhi. 23 April is also observed as the "Khongjom Day", marking the occasion of the battle of Khongjom.[17][18]

See also

Notes

- Perhaps a half-brother.[7]

- From Sanskrit yuvarāja, also spelt yubraj or jubraj in the northeast India.

- It is reported that Kulachandra Singh was absent at the time of the coup. So his role in the affair is not clear.[9]

- According to the Manipur State Archives, they were executed upon the orders of Tikenajit Singh.[1]

References

- "The Anglo Manipur War 1891 and its Consequences". Manipur State Archives. 19 January 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- Sharma, Hanjabam Shukhdeba (2010), Self-determination movement in Manipur, Tata Institute of Social Sciences/Shodhganga, Chapter 3

- "No. 26192". The London Gazette. 14 August 1891. p. 4372.

- "No. 26192". The London Gazette. 14 August 1891. p. 4370.

- Phanjoubam, Pradip (2015), The Northeast Question: Conflicts and frontiers, Routledge, pp. 3–4, ISBN 978-1-317-34004-1

- Reynolds, K. D. (2010). "Grimwood [née Moore; other married name Miller], Ethel Brabazon [pseud. Ethel St Clair Grimwood] (1867–1928), the heroine of Manipur". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/101006.

- Phanjoubam, Bleeding Manipur & 2003 (128).

- Prior, Katherine (2004). "Quinton, James Wallace (1834–1891), administrator in India". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/22968.

- Lee-Warner, Sir William (1894), The Protected Princes of India, Macmillan and Company, pp. 171–172

- Temple, The Manipur Bue-Book (1891), p. 918.

- Temple, The Manipur Bue-Book (1891), pp. 918–919.

- Temple, The Manipur Bue-Book (1891), p. 919: "The Regent Juberaj is to understand that if he is recognised as Maharaja this recognition is to be owing to the will of the British Government, and not to the successful rebellion of his brother the Senapati—in other words, he is to reign as the vassal of the British Paramount, and not as the puppet of his strong-minded brother the Senapati."

- Temple, The Manipur Bue-Book (1891), pp. 919–920 (Government of India's report to the Secretary of State in London)

- Temple, The Manipur Bue-Book (1891), p. 921.

- Phanjoubam, Bleeding Manipur (2003), p. 133.

- Ahmad 2006, pp. 62–65.

- "Tourism discovers Khongjom – Ibobi wants war cemetery developed into tourist spot". Calcutta Telegraph. 13 August 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- "August 13: Patriots' Day "Freedom They Lost, But Love Of Freedom They Retained"". Manipur Online. 13 August 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- "India General Service Medal (1854–1895), with bar for N. E. Frontier 1891, awarded to Subadar Jangbir Rana, 1892". Fitzwilliam Museum. Archived from the original on 11 June 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

Bibliography

- Ahmad, Maj Rifat Nadeem, and Ahmed, Maj Gen Rafiuddin. (2006). Unfaded Glory: The 8th Punjab Regiment 1798–1956. Abbottabad: The Baloch Regimental Centre.

- Tarapot, Phanjoubam (2003), Bleeding Manipur, Har-Anand Publications, ISBN 978-81-241-0902-1

- Temple, Richard (June 1891), "The Manipur Blue-Book", The Contemporary Review, 1866–1900, 59: 917–924 – via ProQuest