Ottoman Algeria

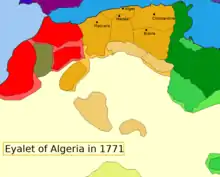

The Regency of Algiers[lower-alpha 1] (in Arabic: Al Jazâ'ir),[lower-alpha 2] was a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire in North Africa lasting from 1516 to 1830, when it was conquered by the French. Situated between the regency of Tunis in the east and the Sultanate of Morocco (from 1553) in the west (and the Spanish and Portuguese possessions of North Africa), the Regency originally extended its borders from La Calle in the east to Trara in the west and from Algiers to Biskra,[12] and after spread to the present eastern and western borders of Algeria.[13] The country was governed by governors appointed by the Ottoman Sultan (1518-1659), rulers appointed by the Odjak of Algiers (1659-1710), and then Sultans elected by the Divan of Algiers.

The Regency of Algiers الجزائر (Arabic) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1516–1830 | |||||||||||||||

Flag[2]

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||||||

.png.webp) Map of the Regency of Algiers in 1609 | |||||||||||||||

| Status | Ottoman Vassal | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Algiers | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Arabic (official, government, religious, literature), Berber, Ottoman Turkish (elite, diplomatic) | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Islam (Maliki and Hanafi), Judaism | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Beylerbeylik (1518-1590) then Eyalet (1590-1830) of the Ottoman Empire | ||||||||||||||

| Dey | |||||||||||||||

• 1516-1518 | Oruç Reis | ||||||||||||||

• 1818-1830 | Hussein Dey | ||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||

• Established | 1516 | ||||||||||||||

| 1830 | |||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||

• 1808 | 3,000,000 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Algeria |

|

History

Establishment

From 1496, the Spanish conquered numerous possessions on the North African coast, which had been captured since 1496: Melilla (1496), Mers El Kébir (1505), Oran (1509), Bougie (1510), Tripoli (1510), Algiers, Shershell, Dellys, and Tenes.[14]

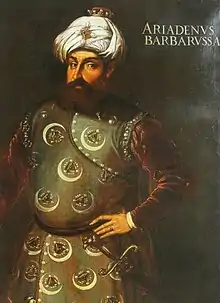

Around the same time, the Ottoman privateer brothers Oruç and Hayreddin—both known to Europeans as Barbarossa, or "Red Beard"—were operating successfully off Tunisia under the Hafsids. In 1516, Oruç moved his base of operations to Algiers and asked for the protection of the Ottoman Empire in 1517, but was killed in 1518 during his invasion of the Kingdom of Tlemcen. Hayreddin succeeded him as military commander of Algiers.[15]

Occupation of Algiers

Oruç, Hayreddin Barbarossa's brother, captured Algiers in 1516, apart from the Spanish Peñón of Algiers. Following the death of Oruç in 1518 at the hand of the Spanish in the Fall of Tlemcen, Barbarossa requested the assistance of the Ottoman Empire, in exchange for acknowledging Ottoman authority in his dominions.[16] Before Ottoman help could arrive, the Spanish retook the city of Algiers in 1519. Barbarossa recaptured the city definitively in 1525, and in 1529 the Spanish Peñon in the capture of Algiers.[16]

Base in the war against Spain

Hayreddin Barbarossa established the military basis of the regency. The Ottomans provided a supporting garrison of 2,000 Turkish troops with artillery.[16] He left Hasan Agha in command as his deputy when he had to leave for Constantinople in 1533.[17]

The son of Barbarossa, Hasan Pashan was in 1544 when his father retired, the first governor of the Regency to be directly appointed by the Ottoman Empire. He took the title of beylerbey.[17] Algiers became a base in the war against Spain, and also in the Ottoman conflicts with Morocco.

Beylerbeys continued to be nominated for unlimited tenures until 1587. After Spain had sent an embassy to Constantinople in 1578 to negotiate a truce, leading to a formal peace in August 1580, the Regency of Algiers was a formal Ottoman territory, rather than just a military base in the war against Spain.[17] At this time, the Ottoman Empire set up a regular Ottoman administration in Algiers and its dependencies, headed by Pashas, with 3-year terms to help considate Ottoman power in the Maghreb.

Mediterranean privateer

Despite the end of formal hostilities with Spain in 1580, attacks on Christian and especially Catholic shipping, with slavery for the captured, became prevalent in Algiers and were actually the main industry and source of revenues of the Regency.[18]

In the early 17th century, Algiers also became, along with other North African ports such as Tunis, one of the bases for Anglo-Turkish piracy. There were as many as 8,000 renegades in the city in 1634.[18][19] (Renegades were former Christians, sometimes fleeing the law, who voluntarily moved to Muslim territory and converted to Islam.) Hayreddin Barbarossa is credited with tearing down the Peñón of Algiers and using the stone to build the inner harbor.[20]

A contemporary letter states:

"The infinity of goods, merchandise jewels and treasure taken by our English pirates daily from Christians and carried to Allarach [ Larache, in Morocco], Algire and Tunis to the great enriching of Mores and Turks and impoverishing of Christians"

— Contemporary letter sent from Portugal to England.[21]

Privateer and slavery of Christians originating from Algiers were a major problem throughout the centuries, leading to regular punitive expeditions by European powers. Spain (1567, 1775, 1783), Denmark (1770), France (1661, 1665, 1682, 1683, 1688), England (1622, 1655, 1672), all led naval bombardments against Algiers.[18] Abraham Duquesne fought the Barbary pirates in 1681 and bombarded Algiers between 1682 and 1683, to help Christian captives.[22]

Danish–Algerian War

In the mid-1700s Dano-Norwegian trade in the Mediterranean expanded. In order to protect the lucrative business against piracy, Denmark–Norway had secured a peace deal with the states of Barbary Coast. It involved paying an annual tribute to the individual rulers and additionally to the States.

In 1766, Algiers had a new ruler, dey Baba Mohammed ben-Osman. He demanded that the annual payment made by Denmark-Norway should be increased, and he should receive new gifts. Denmark–Norway refused the demands. Shortly after, Algerian pirates hijacked three Dano-Norwegian ships and allowed the crew to be sold as slaves.

They threatened to bombard the Algerian capital if the Algerians did not agree to a new peace deal on Danish terms. Algiers was not intimidated by the fleet, the fleet was of 2 frigates, 2 bomb galiot and 4 ship of the line.

Algerian-Sharifian War

In the west, the Algerian-Cherifian conflicts shaped the western border of Algeria.[23]

Barbary Wars

During the early 19th century, the Ottoman Algiers again resorted to widespread piracy against shipping from Europe and the young United States of America, mainly due to internal fiscal difficulties.[18] This in turn led to the First Barbary War and Second Barbary Wars, which culminated in August 1816 when Lord Exmouth executed a naval bombardment of Algiers.[24] The Barbary Wars resulted on a major victory for the American Navy.

French invasion

During the Napoleonic Wars, the Regency of Algiers had greatly benefited from trade in the Mediterranean, and of the massive imports of food by France, largely bought on credit by France. In 1827, Hussein Dey, Algeria's Ottoman ruler, demanded that the French pay a 31-year-old debt contracted in 1799 by purchasing supplies to feed the soldiers of the Napoleonic Campaign in Egypt.

The French consul Pierre Deval refused to give answers satisfactory to the dey, and in an outburst of anger, Hussein Dey touched the consul with his fan. Charles X used this as an excuse to break diplomatic relations. The Regency of Algiers would end with the French invasion of Algiers in 1830, followed by subsequent French rule for the next 132 years.[18]

Political status

After its conquest by Turks, Algeria became a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire. The Regency was successively governed by Beylerbeys (1518–70), Pachas (1570–1659), Aghas (1659–71), then Deys (1671–1830), on behalf of the Ottoman Sultan.

Until 1671, Beylerbeys, Pachas and Aghas were appointed by the Ottoman sultan and were subjucted to him. After 1671, the Regency acquired a large degree of autonomy and became a military republic, ruled in the name of the Ottoman sultan by Deys, officers chosen by the Ottoman janissary militia.[17] In 1710 Baba Ali Chaouche, who just took over Algiers refused to accept the envoy from the Ottoman sultan, which angered the already unrestive Ottoman Janissaries. He defeated them, and signed a treaty with the Ottoman Sultan which recognized his de facto independence.[25] From 1718 onwards, the Deys were elected by the Divan, an assembly aimed to represent the interests of different factions in the country, such as the Nobles, the Rais', the Turkish Janissaries, the Native, and Kouloughli janissaries, and the Ulama.

Administration

Territorial management

The Regency was composed of various beyliks (provinces) under the authority of beys (vassals): the Beylik of Constantine in the east, Beylik of Titteri in Médéa in the Titteri and Mazouna, then the Beylik of the West in Mascara and then Oran in the west. Each beylik was divided into outan (counties) with at their head the caïds directly under the bey. To administer the interior of the country, the administration relied on the tribes said makhzen. These tribes were responsible for securing order and collecting taxes on the tributary regions of the country. It was through this system that, for three centuries, the State of Algiers extended its authority over the north of Algeria. However, society was still divided into tribes and dominated by maraboutic brotherhoods or local djouads (nobles). Several regions of the country thus only lightly recognised the authority of Algiers. Throughout its history, they formed numerous revolts, confederations, tribal fiefs or sultanates that fought with the regency for control. Before 1830, out of the 516 political units, a total of 200 principalities or tribes were considered independent because they controlled over 60% of the territory in Algeria and refused to pay taxes to Algiers.

Diwan

The Divan of Algiers was started in the 16th century by the Odjak. It was seated in the Jenina Palace. This assembly, initially led by a Janissary Agha would soon go from a way to administer the Odjack to a central part of the country's administration.[26] This change started in the 17th century, and the Diwan became an important part of the state, albeit it was still dominated by the Janissaries. Around 1628 the Divan was expanded to include 2 subdivisions. One called the private (Janissary) Divan (diwan khass), and the Public, or Grand Diwan (diwan âm). The latter was composed of Hanafi scholars and preachers, the raïs, and native notables. It numbered between 800-1500 people, but it was still less important than the Private Divan used by the Janissaries. During the period when Algiers was ruled by Aghas, the leader of the Divan was also the leader of the country. The Agha called himself the Hakem.[27] In the 18th century, following the coup of Baba Ali Chaouche, the Divan was reformed. The grand divan was now the dominant one, and it was the main body of the government which elected the leader of the country, the Dey-Pacha. This new reformed Divan was composed of:

- Officials

- Ministers

- Tribal elders

- Moorish, Arab, and Berber Nobles

- Janissary commanders (Kouloughlis, and Turks)

- Rais (Pirate captains)

- Ulema

The Janissary Divan remained completely under the control of the Turkish Janissary commanders.

This Divan normally met once a week, albeit this wasn't always true, since if the Dey felt powerful enough he could simply stop the Divan's functions. At the beginning of their mandate, the deys consulted the divan on all important questions.[28]

However, as the Deys became stronger, the Divan became weaker. By the 19th century, the Divan was mostly ignored, especially the private Janissary Divan. The dey's council, (also called Divan by the British) became more and more powerful. Dey Ali Khodja weakened the Janissary Divan to the point where they held no power. This angered the Turkish Janissaries, who launched a coup against the Dey. The coup failed, since the Dey successfully raised an army of Kabyle Zwawa cavalry, Arab infantry and Kouloughli troops. Many of the Turkish Janissaries were executed, while the rest fled. The Janissary Divan was abolished, and the Grand Divan was moved to the citadel of the Casbah.

Demography

As of 1808, the population of the Regency of Algiers numbered around 3 million people, of whom 10,000 were 'Turks' (including people from Kurdish, Greek and Albanian ancestry[29]) and 5,000 Kouloughli civilians (from the Turkish kul oğlu, "son of slaves (Janissaries)", i.e. creole of Turks and local women).[30] By 1830, more than 17,000 Jews were living in the Regency.[31]

See also

Notes

- In the historiography relating to the regency of Algiers, it has been named "Kingdom of Algiers",[4] "republic of Algiers",[5] "State of Algiers",[6] "State of El-Djazair",[7] "Ottoman Regency of Algiers",[6] "precolonial Algeria", "Ottoman Algeria",[8] etc. The Algerian historian Mahfoud Kaddache said that "Algeria was first a regency, a kingdom-province of Ottoman Empire and then a State with a large autonomy, even independent, called sometimes kingdom or military republic by the historians, but still recognizing the spiritual authority of the caliph of Istanbul".[9]

- The French historians Ahmed Koulakssis and Gilbert Meynier write that "it's the same word, in international treaty which describes the city and the country it commands : Al Jazâ’ir".[10] Gilbert Meynier adds that "even if the path is difficult to build a State on the rubble of Zayanid's and Hafsids States [...] now, we speak about dawla al-Jaza’ir[11] (power-state of Algiers)"...

References

- Gabor Agoston; Bruce Alan Masters (2009-01-01). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. Infobase Publishing. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-4381-1025-7. Retrieved 2013-02-25.

- The red-and-yellow-striped banner flew over the city of Algiers in 1776 according to an article in The Flag Bulletin, Volume 25 (1986), p. 166. F. C. Leiner, The End of Barbary Terror: America's 1815 War Against the Pirates of North Africa (Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 7, describes a green flag with white crescent and stars being raised on Algerian pirate vessels in 1812. According to Tarek Kahlaoui, Creating the Mediterranean: Maps and the Islamic Imagination (Brill, 2018), p. 216, the city of Algiers is represented by a flag of red, yellow and green horizontal stripes in an Ottoman atlas of 1551. According to an 1849 engraving by Gustav Feldweg, the former Algerian flag was an arm holding a sword on a red field and the flag of the Algerian corsairs was a skull and crossbones on the same field. See also Historical flags of Algeria.

- Gabor Agoston; Bruce Alan Masters (2009-01-01). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. Infobase Publishing. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-4381-1025-7. Retrieved 2013-02-25.

- (Tassy 1725, pp. 1, 3, 5, 7, 12, 15 et al)

- (Tassy 1725, p. 300 chap. XX)

- (Ghalem & Ramaoun 2000, p. 27)

- (Kaddache 1998, p. 3)

- (Panzac 1995, p. 62)

- (Kaddache 1998, p. 233)

- (Koulakssis & Meynier 1987, p. 17)

- (Meynier 2010, p. 315)

- Collective coordinated by Hassan Ramaoun, L'Algérie : histoire, société et culture, Casbah Editions, 2000, 351 p. (ISBN 9961-64-189-2), p. 27

- Hélène Blais. "La longue histoire de la délimitation des frontières de l'Algérie", in Abderrahmane Bouchène, Jean-Pierre Peyroulou, Ouanassa Siari Tengour and Sylvie Thénault, Histoire de l'Algérie à la période coloniale : 1830-1962, Éditions La Découverte et Éditions Barzakh, 2012 (ISBN 9782707173263), p. 110-113.

- An Historical Geography of the Ottoman Empire p.107ff

- ↑ Kamel Filali, L'Algérie mystique : Des marabouts fondateurs aux khwân insurgés, XVe-XIXe siècles, Paris, Publisud, coll. « Espaces méditerranéens », 2002, 214 p. (ISBN 2866008952), p. 56

- Naylorp, by Phillip Chiviges (2009). North Africa: a history from antiquity to the present. University of Texas Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-292-71922-4. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- Abun-Nasr, Jamil M. (1987). A History of the Maghrib in the Islamic Period. Cambridge University Press. p. 160. ISBN 9780521337670.

[In 1671] Ottoman Algeria became a military republic, ruled in the name of the Ottoman sultan by officers chosen by and in the interest of the Ujaq.

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (30 January 2008). Historic cities of the Islamic world. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 24. ISBN 978-90-04-15388-2. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- Tenenti, Alberto Tenenti (1967). Piracy and the Decline of Venice, 1580-1615. University of California Press. p. 81. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- "Moonlight View, with Lighthouse, Algiers, Algeria". World Digital Library. 1899. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- Harris, Jonathan Gil (2003). Sick Economies: Drama, mercantilism, and disease in Shakespeare's England. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 152ff. ISBN 978-0-8122-3773-3. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- Martin, Henri (1864). Martin's History of France. Walker, Wise & Co. p. 522. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- Tayeb Chenntouf (1999). "" La dynamique de la frontière au Maghreb. ", Des frontières en Afrique du xiie au xxe siècle" (PDF). unesdoc.unesco.org. Retrieved 2020-07-17.

- Kidd, Charles, Williamson, David (editors). Debrett's Peerage and Baronetage (1990 edition). New York: St Martin's Press, 199

- Biographie universelle, ancienne et moderne (in French). 1834.

- Boyer, P. (1970). "Des Pachas Triennaux à la révolution d'Ali Khodja Dey (1571-1817)". Revue Historique. 244 (1 (495)): 99–124. ISSN 0035-3264. JSTOR 40951507.

- Boyer, Pierre (1973). "La révolution dite des "Aghas" dans la régence d'Alger (1659-1671)". Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée. 13 (1): 159–170. doi:10.3406/remmm.1973.1200.

- Mahfoud Kaddache, L'Algérie des Algériens, EDIF 2000, 2009, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)413

- Isichei, Elizabeth Isichei (1997). A history of African societies to 1870. Cambridge University Press. p. 263. ISBN 0-521-45444-1. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- Isichei, Elizabeth Isichei (1997). A history of African societies to 1870. Cambridge University Press. p. 273. ISBN 0-521-45444-1. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- Yardeni, Myriam (1983). Les juifs dans l'histoire de France: premier colloque internationale de Haïfa. BRILL. p. 167. ISBN 9789004060272. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

Bibliography

- Konstam, Angus (2016). The Barbary Pirates. 15th–17th Centuries. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4728-1543-9.

.png.webp)