Gemma Frisius

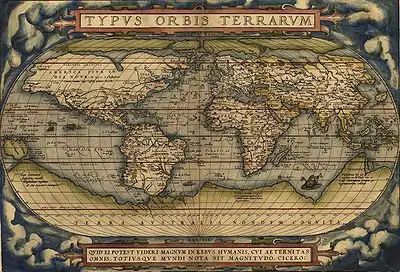

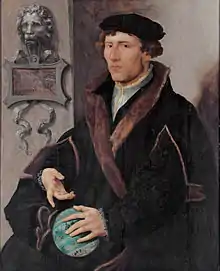

Gemma Frisius (/ˈfrɪziəs/; born Jemme Reinerszoon;[1] December 9, 1508 – May 25, 1555) was a Dutch physician, mathematician, cartographer, philosopher, and instrument maker. He created important globes, improved the mathematical instruments of his day and applied mathematics in new ways to surveying and navigation. Gemma's rings are named after him. Along with Gerardus Mercator and Abraham Ortelius, Frisius is often considered one of the founders of the Netherlandish school of cartography and significantly helped lay the foundations for the school's golden age (approximately 1570s–1670s).

Biography

Frisius was born in Dokkum, Friesland (present-day Netherlands), of poor parents who died when he was young. He moved to Groningen and later studied at the University of Leuven (Louvain), Belgium, beginning in 1525. He received the degree of MD in 1536 and remained on the faculty of medicine of Leuven for the rest of his life where, in addition to teaching medicine, he also taught mathematics, astronomy and geography. His oldest son, Cornelius Gemma, edited a posthumous volume of his work and continued to work with Ptolemaic astronomical models.

.jpg.webp)

One of his most influential teachers at Leuven was Franciscus Monachus who, circa 1527, had constructed a famous globe in collaboration with the Leuven goldsmith Gaspar van der Heyden[2] Under the guidance of Monachus and the technical assistance of Van der Heyden, Frisius set up a workshop to produce globes and mathematical instruments which were praised for their quality and accuracy by contemporary astronomers such as Tycho Brahe. Of particular fame were the terrestrial globe of 1536 and the celestial globe of 1537. On the first of these Frisius is described as the author with technical assistance from Van der Heyden and engraving by Gerardus Mercator who was a pupil of Frisius at the time. On the second globe Mercator is promoted to co-author.

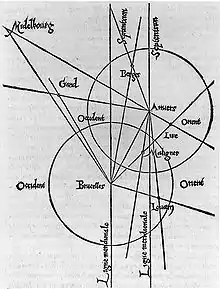

In 1533, he described for the first time the method of triangulation still used today in surveying (see diagram). Having established a baseline, e.g., in this case, the cities of Brussels and Antwerp, the location of other cities, e.g. Middelburg, Ghent etc., can be found by taking a compass direction from each end of the baseline, and plotting where the two directions cross. This was only a theoretical presentation of the concept — due to topographical restrictions, it is impossible to see Middelburg from either Brussels or Antwerp. Nevertheless, the figure soon became well known all across Europe.

Twenty years later, in ~1553, he was the first to describe how an accurate clock could be used to determine longitude.[3] Jean-Baptiste Morin (1583–1656) did not believe that Frisius' method for calculating longitude would work, remarking, "I do not know if the Devil will succeed in making a longitude timekeeper but it is folly for man to try."[4] In the event it took two centuries before John Harrison produced a sufficiently accurate clock.

Frisius created or improved many instruments, including the cross-staff, the astrolabe, and the astronomical rings (also known as "Gemma's rings"). His students included Gerardus Mercator (who became his collaborator), Johannes Stadius, John Dee, Andreas Vesalius and Rembert Dodoens.

Frisius died in Leuven at the age of 46. According to an account by his son, Cornelius, Gemma died from kidney stones, which he had suffered from for a minimum of 7 years.[5]

A lunar crater has been named after him. Gualterus Arsenius, the 16th century scientific instrument maker, was his nephew.

Works

- Cosmographia (1529) von Petrus Apianus, annotated by Gemma Frisius

- De principiis astronomiae et cosmographiae (1530)

- De usu globi (1530)

- Libellus de locorum describendorum ratione (1533)

- Arithmeticae practicae methodus facilis (1540)

- De annuli astronomici usu[6] (1540)

- De radio astronomico et geometrico (1545)

- De astrolabio catholico (1556)

Page from Cosmographia

Page from Cosmographia Frontispiece of Arithmeticae practicae methodus facilis

Frontispiece of Arithmeticae practicae methodus facilis

Notes

- He was cited as Jemme Reinersz in the 1533 edition of Peter Apian's Cosmographia.

- There is no English biography of Van der Heyden (or Gaspar a Myrica c1496—c1549) but he has an entry in the Dutch Nationaal Biografisch Woordenboek.

- Pogo, A. (1935-02-01). "Gemma Frisius, His Method of Determining Differences of Longitude by Transporting Timepieces (1530), and His Treatise on Triangulation (1533)". Isis. 22 (2): 469–506. doi:10.1086/346920. ISSN 0021-1753.

- "Longitude1". Groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk. Retrieved 2013-03-19.

- Gemma Frisius, Tycho Brahe & Snellius & Their Triangulations, N.D. Haasbroek, Rijkscommissie Voor Geodesie, Delft, Netherlands, 1968, p. 10 Archived 2011-07-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Usus annuli astronomici - Rainer Gemma Frisius. 1548. Retrieved 2013-03-19 – via Internet Archive.

annuli astronomici.

Further reading

- N. Haasbroek: Gemma Frisius, Tycho Brahe and Snellius and their triangulations. Delft 1968.

- Robert Haardt: The globe of Gemma Frisius. Imago mundi, Bd. 9, 1952.

- W. Karrow: Mapmakers of the Sixteenth Century and Their Maps. Chicago 1993.

- G. Kish: Medicina, mensura, mathematica: The Life and Works of Gemma Frisius. Minneapolis 1967, sowie sein Artikel in Dictionary of Scientific Biography

- A. Pogo: Gemma Frisius, his method of determining longitude. In: Isis. Bd. 22, 1935, S.469-485.

- Moritz Cantor (1878), "Gemma-Frisius, Rainer", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB) (in German), 8, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 555–556

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gemma Frisius. |

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Regnier Gemma Frisius", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- Gemma (Jemme Reinerszoon) Frisius at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- Description of the Camera Obscura in 1544 by Frisius

- Arithmeticae practicae methodus facilis From the John Davis Batchelder Collection in the Rare Book and Special Collection Division at the Library of Congress