Abel Tasman

Abel Janszoon Tasman (Dutch: [ˈɑbəl ˈjɑnsoːn ˈtɑsmɑn]; 1603 – 10 October 1659) was a Dutch seafarer, explorer, and merchant, best known for his voyages of 1642 and 1644 in the service of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). He was the first known European explorer to reach the islands of Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania), Fiji and New Zealand.

Abel Tasman | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Detail from portrait by Jacob Gerritsz. Cuyp, c. 1637 | |

| Born | 1603 |

| Died | 10 October 1659 (aged 55–56) |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Occupation | Navigator, explorer sea captain |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | Claesjen Tasman (daughter) |

Origins and early life

Abel Tasman was born around 1603 in Lutjegast, a small village in the province of Groningen, in the north of the Netherlands. The oldest available source mentioning him is dated 27 December 1631 when, as a seafarer living in Amsterdam, the 28-year-old became engaged to marry 21-year-old Jannetje Tjaers, of Palmstraat in the Jordaan district of the city.[3][4]

Relocation to the Dutch East Indies

Employed by the Dutch East India Company (VOC), Tasman sailed from Texel to Batavia, now Jakarta, in 1633 taking the southern Brouwer Route. During this period, Tasman took part in a voyage to Seram Island; the locals had sold spices to other European nationalities than the Dutch. He had a narrow escape from death, when in an incautious landing several of his companions were killed by people of Seram.[5]

In August 1637, Tasman was back in Amsterdam, and the following year he signed on for another ten years and took his wife with him to Batavia. On 25 March 1638 he tried to sell his property in the Jordaan, but the purchase was cancelled.

He was second-in-command of a 1639 exploration expedition in the north Pacific under Matthijs Quast. The fleet included the ships Engel and Gracht and reached Fort Zeelandia (Dutch Formosa) and Deshima.

First major voyage

In August 1642, the Council of the Indies, consisting of Antonie van Diemen, Cornelis van der Lijn, Joan Maetsuycker, Justus Schouten, Salomon Sweers, Cornelis Witsen, and Pieter Boreel in Batavia despatched Tasman and Franchoijs Jacobszoon Visscher on a voyage of exploration to little-charted areas east of the Cape of Good Hope, west of Staten Land (near the Cape Horn of South America) and south of the Solomon Islands.[6]

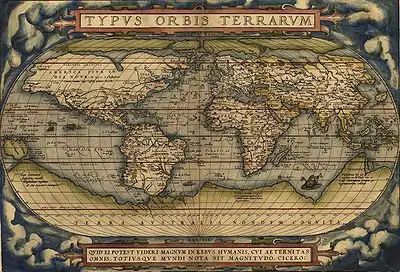

One of the objectives was to obtain knowledge of "all the totally unknown" Provinces of Beach.[7] This was a purported yet non-existent landmass alleged to have plentiful gold, which had appeared on European maps since the 15th century, as a result of an error in some editions of Marco Polo's works.

The expedition was to use two small ships, Heemskerck and Zeehaen.

Mauritius

In accordance with Visscher's directions, Tasman sailed from Batavia on 14 August 1642[8] and arrived at Mauritius on 5 September 1642, according to the captain's journal.[9] The reason for this was the crew could be fed well on the island; there was plenty of fresh water and timber to repair the ships. Tasman got the assistance of the governor Adriaan van der Stel.

Because of the prevailing winds, Mauritius was chosen as a turning point. After a four-week stay on the island, both ships left on 8 October using the Roaring Forties to sail east as fast as possible. (No one had gone as far as Pieter Nuyts in 1626/27.) On 7 November, snow and hail influenced the ship's council to alter course to a more north-easterly direction,[10] expecting to arrive one day at the Solomon Islands.

Tasmania

On 24 November 1642, Tasman reached and sighted the west coast of Tasmania, north of Macquarie Harbour.[11] He named his discovery Van Diemen's Land, after Antonio van Diemen, Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies.

Proceeding south, Tasman skirted the southern end of Tasmania and turned north-east. He then tried to work his two ships into Adventure Bay on the east coast of South Bruny Island, where he was blown out to sea by a storm. This area he named Storm Bay. Two days later, on December 1, Tasman anchored to the north of Cape Frederick Hendrick just north of the Forestier Peninsula. On December 2, two ship's boats under the command of the Pilot, Major Visscher, rowed through the Marion Narrows into Blackman Bay, and across the west to the outflow of Boomer Creek where they gathered some edible "greens".[12] Tasman named Frederick Hendrik Bay, which included the present North Bay, Marion Bay and the inlet Blackman Bay (the name Frederick Henry Bay was mistakenly transferred to its present location by Marion Dufresne in 1772). The next day, an attempt was made to land in North Bay. However, because the sea was too rough, the carpenter swam through the surf and planted the Dutch flag. Tasman then claimed formal possession of the land, on 3 December 1642.[13]

For two more days, he continued to follow the east coast northward to see how far it went. When the land veered to the north-west at Eddystone Point,[14] he tried to keep in with it but his ships were suddenly hit by the Roaring Forties howling through Bass Strait.[15] The impenetrable wind wall indicated that here was a strait, not a bay. Tasman was on a mission to find the Southern Continent, not more islands, so he abruptly turned away to the east and continued his continent-hunting.[16]

New Zealand

After some exploration, Tasman had intended to proceed in a northerly direction but as the wind was unfavourable he steered east. The expedition endured an extremely rough voyage and in one of his diary entries Tasman credited his compass, claiming it was the only thing that had kept him alive.

On 13 December 1642 they sighted land on the north-west coast of the South Island, New Zealand, becoming the first Europeans to sight New Zealand.[18] Tasman named it Staten Landt "in honour of the States General" (Dutch parliament).[19] He wrote, "it is possible that this land joins to the Staten Landt but it is uncertain",[20] referring to Isla de los Estados, a landmass of the same name at the southern tip of South America, encountered by the Dutch navigator Jacob Le Maire in 1616.[21] However, in 1643 Brouwer's expedition to Valdivia found out that Staaten Landt was separated by sea from any the hypothetical Southern Land.[22][23][24] Tasman continued: "We believe that this is the mainland coast of the unknown Southland."[25] Tasman thought he had found the western side of the long-imagined Terra Australis that stretched across the Pacific to near the southern tip of South America.[26]

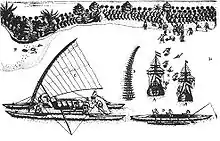

After sailing north, then east for five days, the expedition anchored about 7 km from the coast off what is now believed to have been Golden Bay. Tasman sent ship's boats to gather water, but one of his boats was attacked by Māori in a double-hulled waka (canoe) and four of his men were killed with mere (clubs).

In the evening about one hour after sunset we saw many lights on land and four vessels near the shore, two of which betook themselves towards us. When our two boats returned to the ships reporting that they had found not less than thirteen fathoms of water, and with the sinking of the sun (which sank behind the high land) they had been still about half a mile from the shore. After our people had been on board about one glass, people in the two canoes began to call out to us in gruff, hollow voices. We could not in the least understand any of it; however, when they called out again several times we called back to them as a token answer. But they did not come nearer than a stone's shot. They also blew many times on an instrument, which produced a sound like the moors' trumpets. We had one of our sailors (who could play somewhat on the trumpet) play some tunes to them in answer."[9]

As Tasman sailed out of the bay he observed 22 waka near the shore, of which "eleven swarming with people came off towards us." The waka approached the Zeehaen which fired and hit a man in the largest waka holding a small white flag. Canister shot also hit the side of a waka.[9][27] Archaeological research has shown the Dutch had tried to land at a major agricultural area, which the Māori may have been trying to protect.[28] Tasman named the area "Murderers' Bay".

The expedition then sailed north, sighting Cook Strait, which it mistook for a bight and named "Zeehaen's Bight". Two names that the expedition gave to landmarks in the far north of New Zealand still endure: Cape Maria van Diemen and Three Kings Islands. (Kaap Pieter Boreels was renamed Cape Egmont by Captain James Cook 125 years later.)

Return voyage

En route back to Batavia, Tasman came across the Tongan archipelago on 20 January 1643. While passing the Fiji Islands Tasman's ships came close to being wrecked on the dangerous reefs of the north-eastern part of the Fiji group. He charted the eastern tip of Vanua Levu and Cikobia before making his way back into the open sea.

The expedition turned north-west towards New Guinea and arrived at Batavia on 15 June 1643.[13]

Second major voyage

Tasman left Batavia on 30 January 1644 on his second voyage with three ships (Limmen, Zeemeeuw and the tender Braek). He followed the south coast of New Guinea eastwards in an attempt to find a passage to the eastern side of New Holland. However, he missed the Torres Strait between New Guinea and Australia, probably due to the numerous reefs and islands obscuring potential routes, and continued his voyage by following the shore of the Gulf of Carpentaria westwards along the north Australian coast. He mapped the north coast of Australia, making observations on New Holland and its people.[29] He arrived back in Batavia in August 1644.

From the point of view of the Dutch East India Company, Tasman's explorations were a disappointment: he had neither found a promising area for trade nor a useful new shipping route. Although received modestly, the company was upset to a degree that Tasman did not fully explore the lands he found, and decided that a more "persistent explorer" should be chosen for any future expeditions.[30] For over a century, until the era of James Cook, Tasmania and New Zealand were not visited by Europeans – mainland Australia was visited, but usually only by accident.

Later life

On 2 November 1644, Abel Tasman was appointed a member of the Council of Justice at Batavia. He went to Sumatra in 1646, and in August 1647 to Siam (now Thailand) with letters from the company to the King. In May 1648, he was in charge of an expedition sent to Manila to try to intercept and loot the Spanish silver ships coming from America, but he had no success and returned to Batavia in January 1649. In November 1649, he was charged and found guilty of having in the previous year hanged one of his men without trial, was suspended from his office of commander, fined, and made to pay compensation to the relatives of the sailor. On 5 January 1651, he was formally reinstated in his rank and spent his remaining years at Batavia. He was in good circumstances, being one of the larger landowners in the town. He died at Batavia on 10 October 1659 and was survived by his second wife and a daughter by his first wife. His property was divided between his wife and his daughter by his first marriage. In his will (dating from 1657[31]), he left 25 guilders to the poor of his village Lutjegast.[32]

Although Tasman's pilot, Frans Visscher, published Memoir concerning the discovery of the South land in 1642, Tasman's detailed journal was not published until 1898; however, some of his charts and maps were in general circulation and used by subsequent explorers.[29]

Legacy

Tasman's ten-month voyage in 1642–43 had significant consequences. By circumnavigating Australia (albeit at a distance) Tasman proved that the small fifth continent was not joined to any larger sixth continent, such as the long-imagined Southern Continent. Further, Tasman's suggestion that New Zealand was the western side of that Southern Continent was seized upon by many European cartographers who, for the next century, depicted New Zealand as the west coast of a Terra Australis rising gradually from the waters around Tierra del Fuego. This theory was eventually disproved when Captain Cook circumnavigated New Zealand in 1769.[33]

Multiple places have been named after Tasman, including:

- the Australian island and state of Tasmania, renamed after him, formerly Van Diemen's land. It includes features such as:

- the Tasman Peninsula

- the Tasman Bridge

- the Tasman Highway

- the Tasman Sea

- in New Zealand:

Also named after Tasman are:

- Tasman Pulp and Paper company, A large pulp and paper producer in Kawerau New Zealand

- Abel Tasman Drive, in Takaka

- The former passenger/vehicle ferry Abel Tasman

- The Able Tasmans – an indie band from Auckland, New Zealand

- Tasman, a layout engine for Internet Explorer

- 6594 Tasman (1987 MM1), a main-belt asteroid

- Tasman Drive in San Jose, California, and its Tasman light rail station

- Tasman Road in Claremont, Cape Town, South Africa

- HMNZS Tasman Shore based training Establishment of the Royal New Zealand Navy

- HMAS Tasman is a Hunter-class frigate that is expected to enter service with the Royal Australian Navy in the late 2020s.

His portrait has been on four New Zealand postage stamp issues, on a 1992 5 NZD coin, and on 1963, 1966[34] and 1985 Australian postage stamps.[35]

In the Netherlands, many streets are named after him. In Lutjegast, the village he was born, there is a museum dedicated to his life and travels.

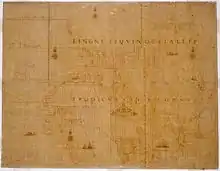

Tasman Map

Held within the collection of the State Library of New South Wales is the Tasman Map, thought to have been drawn by Isaac Gilsemans, or completed under the supervision of Franz Jacobszoon Visscher.[36] The map is also known as the Bonaparte map, as it was once owned by Prince Roland Bonaparte, the great-nephew of Napoleon.[37] The map was completed sometime after 1644 and is based on the original charts drawn during Tasman's first and second voyages.[38] As none of the journals or logs composed during Tasman's second voyage have survived, the Bonaparte map remains as an important contemporary artefact of Tasman's voyage to the northern coast of the Australian continent.[38]

The Tasman map largely reveals the extent of understanding the Dutch had of the Australian continent at the time.[39] The map includes the western and southern coasts of Australia, accidentally encountered by Dutch voyagers as they journeyed by way of the Cape of Good Hope to the VOC headquarters in Batavia.[37] In addition, the map shows the tracks of Tasman's two voyages.[37] Of his second voyage, the map shows the area of the Banda Islands, the southern coast of New Guinea and much of the northern coast of Australia. However, the area of the Torres Strait is shown unexamined; this is despite having been given orders by VOC Council at Batavia to explore the possibility of a channel between New Guinea and the Australian continent.[38][39]

There is debate as to the origin of the map.[40] It is widely believed that the map was produced in Batavia; however, it has also been argued that the map was produced in Amsterdam.[37][40] The authorship of the map has also been debated: while the map is commonly attributed to Tasman, it is now thought to have been the result of a collaboration, probably involving Franchoijs Visscher and Isaack Gilsemans, who took part in both of Tasman's voyages.[7][40] Whether the map was produced in 1644 is also subject to debate, as a VOC company report in December 1644 suggests that at that time no maps showing Tasman's voyages were yet complete.[40]

In 1943, a mosaic version of the map, composed of coloured marble and brass, was inlaid into the vestibule floor of the Mitchell Library in Sydney.[41] The work was commissioned by the Principal Librarian William Ifould, and completed by the Melocco Brothers of Annandale, who also worked on ANZAC War Memorial in Hyde Park and the crypt at St Mary's Cathedral, Sydney.[42][36]

See also

References

- "Treasures : Home". pandora.nla.gov.au. 20 August 2006. Archived from the original on 22 July 2008. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- Cuyp, Jacob. "Portrait of Abel Tasman, his wife and daughter". Item held by National Gallery of Australia. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- "Amsterdam City Archives". stadsarchief.amsterdam.nl. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- Pera, Klaas. "Abel Janszoon Tasman (1603-1659) » Stamboom Helmantel » Genealogie Online". Genealogie Online. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- Forsyth, J. W. Tasman, Abel Janszoon (1603–1659). National Centre of Biography, Australian National University – via Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- Andrew Sharp, The Voyages of Abel Janszoon Tasman, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1968, pp. 25.

- J.E. Heeres, "Abel Janszoon Tasman, His Life and Labours", Abel Tasman's Journal, Los Angeles, 1965, pp.137, 141–2; cited in Andrew Sharp, The Voyages of Abel Janszoon Tasman, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1968, p.24.

- "Abel Janszoon Tasman, the first known European explorer to reach Tasmania and New Zealand and to sight Fiji". robinsonlibrary.com. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- "Tasman Journal". Archived from the original on 29 August 2016. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- "ebooks06/0600611". gutenberg.net.au. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- "Digital Collections - Maps - Monumenta cartographica [cartographic material] : reproductions of unique and rare maps, plans and views in the actual size of the originals : accompanied by cartographical monographs | Original map of Tasmania in December 1642". nla.gov.au. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- Burney, J (1813) A Chronological History of the Voyage and Discoveries in the South Sea of Pacific Ocean L Hansard & Sons, London, p. 70, cited in Potts, B.M. et al (2006) Janet Sommerville's Botanical History of Tasmania University of Tasmania and TMAG

- Beazley 1911.

- Schilder, Günter (1976). Australia unveiled : the share of the Dutch navigators in the discovery of Australia. Amsterdam: Theatrum Orbis Terrarum Ltd. p. 170. ISBN 9022199975.

- Valentyn, Francois (1724–1726). Oud en nieuw Oost-Indien. Dordrecht: J. van Braam. p. vol.3, p.47. ISBN 9789051942347.

- Cameron-Ash, M. (2018). Lying for the Admiralty. Sydney: Rosenberg. p. 105. ISBN 9780648043966.

- "'A view of the Murderers' Bay' – History – Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand". teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- "European discovery of New Zealand". Encyclopedia of New Zealand. 4 March 2009. Archived from the original on 10 November 2010. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- John Bathgate. "The Pamphlet Collection of Sir Robert Stout:Volume 44. Chapter 1, Discovery and Settlement". NZETC. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

He named the country Staaten Land, in honour of the States-General of Holland, in the belief that it was part of the great southern continent.

- Tasman, Abel. "JOURNAL or DESCRIPTION By me Abel Jansz Tasman, Of a Voyage from Batavia for making Discoveries of the Unknown South Land in the year 1642". Project Gutenberg Australia. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- Wilson, John (March 2009). "European discovery of New Zealand – Tasman's achievement". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- Lane, Kris E. (1998). Pillaging the Empire: Piracy in the Americas 1500–1750. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-76560-256-5.

- Kock, Robbert. "Dutch in Chile". Colonial Voyage.com. Archived from the original on 29 February 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- Barros Arana, Diego (2000) [1884]. Historia General de Chile (in Spanish). IV (2 ed.). Santiago, Chile: Editorial Universitaria. p. 280. ISBN 956-11-1535-2.

- Tasman, Abel Jansz. The Huydecoper Journal, 1642-1643. Sydney: Mitchell Library, SLNSW. p. 43.

- Cameron-Ash, M. (2018). Lying for the Admiralty. Sydney: Rosenberg. pp. 21–22. ISBN 9780648043966.

- Diary of Abel Tasman p. 21-22.Random House. 2008

- "First contact violence linked to food". The New Zealand Herald. 23 September 2010. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- Quanchi, Historical Dictionary of the Discovery and Exploration of the Pacific Islands, page 237

- "Abel Tasman's great voyage". Tai Awatea-Knowledge Net. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- "National Archives". Archived from the original on 20 April 2008.

- Robbie Whitmore. "Abel Janszoon Tasman - New Zealand in History - Holland 1603 - 1659". history-nz.org. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- Cameron-Ash, M. (2018). Lying for the Admiralty. Rosenberg. pp. 21–22. ISBN 9780648043966.

- Oceania/Australia : 1963 4/- & 1966 40 cent Tasman and his ship the "Heemskerk", Stamporama

- "Image: 0015370.jpg, (378 × 378 px)". australianstamp.com. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- "The tasman map". Discover Collections. State Library of New South Wales. 2012.

- Hooker, Brian N. (November 2015). "New Light on the Origin of the Tasman-Bonaparte Map". The Globe (78). Retrieved 8 August 2016 – via Informit.

- Patton, Maggie (2014). Pool, David (ed.). Tasman's Legacy. Mapping our world. Canberra: National Library of Australia. pp. 140–142. ISBN 9780642278098.

- Jeans, D.N. (1972). Historical Geography of New South Wales to 1901. Reed Education. p. 24. ISBN 0589091174.

- Anderson, G (2001). The Merchant of the Zeehaen: Isaac Gilsemans and the voyages of Abel Tasman. Wellington: Te Papa Press. pp. 155–158. ISBN 0909010757.

- Tasman Map in the Mitchell Vestibule, State Library of NSW

- Kevin, Catherine (2005). "Melocco, Galliano (1897–1971)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

Sources

- Serle, Percival (1949). "Tasman, Abel". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Sydney: Angus and Robertson.

- Edward Duyker (ed.) The Discovery of Tasmania: Journal Extracts from the Expeditions of Abel Janszoon Tasman and Marc-Joseph Marion Dufresne 1642 & 1772, St David's Park Publishing/Tasmanian Government Printing Office, Hobart, 1992, pp. 106, ISBN 0-7246-2241-1.

- Quanchi, Max (2005). Historical Dictionary of the Discovery and Exploration of the Pacific Islands. The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810853957.

- Beazley, Charles Raymond (1911), , in Chisholm, Hugh (ed.), Encyclopædia Britannica, 26 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 437–438

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Abel Tasman. |