European land exploration of Australia

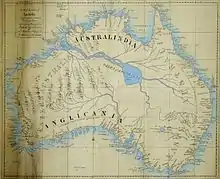

European land exploration of Australia deals with the opening up of the interior of Australia to European settlement which occurred gradually throughout the colonial period, 1788–1900. A number of these explorers are very well known, such as Burke and Wills who are well known for their failed attempt to cross the interior of Australia, as well as Hamilton Hume and Charles Sturt.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Australia |

|

|

|

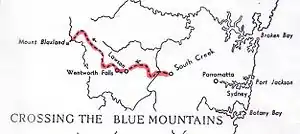

Crossing the Blue Mountains

For many years, plans of westward expansion from Sydney were thwarted by the Great Dividing Range, a large range of mountains which shadows the east coast from the Queensland-New South Wales border to the south coast. The part of the range near Sydney is called the Blue Mountains. After numerous attempts to cross the mountains, Governor Philip Gidley King declared them to be impassable.

William Paterson led an expedition northward along the coast to the Hunter Region in 1801 and up the Paterson River (later named in his honour by Governor King) and in 1804 Paterson led an expedition to Port Dalrymple, in what is now Tasmania, exploring the Tamar River and going up the North Esk River farther than any European had previously gone.[1]

Despite King's pronouncement, some settlers continued to try crossing the mountains. Gregory Blaxland was the first to successfully lead an expedition to cross them in 1813, accompanied by William Lawson, William Wentworth and four servants. This trip paved the way for numerous small expeditions which were undertaken in the following few years.[2]

On 13 November 1813 Governor Lachlan Macquarie sent Government Surveyor, George Evans, across the Blue Mountains to confirm the findings of Blaxland's exploration party. Evans generally followed Blaxland's route, reaching the end of their route on 26 November 1813 at a point Evans named Mount Blaxland. Evans's party then moved on and discovered the Fish River area and further west near the junction of the now named Fish and Campbell Rivers and described two plains in his view, the O'Connell Plains and the Macquarie Plains.[3] On 9 December he reached the site of present-day Bathurst.[4] After the explorations that took seven weeks Governor Macquarie awarded Evans £100 and 1000 acres of land near Richmond in Van Diemens Land (Tasmania). Evans departed for Tasmania in 1814.[3]

In 1814, Governor Lachlan Macquarie approved an offer by William Cox to build a road crossing the Blue Mountains, from Emu Plains, the existing road terminus west of Sydney, to the Bathurst Plains. The first road to cross the Blue Mountains was 12 feet (3.7 m) wide by 101 1⁄2 miles (163.3 km) long, built between 18 July 1814 to 14 January 1815 using 5 freemen, 30 convict labourers and 8 soldiers as guards. Governor Macquarie surveyed the finished road in April 1815,[5] and as a reward Cox was awarded 2,000 acres (810 ha) of land near what is now Bathurst.

On 7 May 1815, Governor Macquarie proclaimed the name of the future town of Bathurst,[6] the first inland town in Australia and intended to be the administrative centre of the western plains of New South Wales.

Inland exploration

Evans was back in New South Wales by 1815 to continue inland explorations.[3] In 1815, Evans was the first colonial explorer to enter the Lachlan Valley, naming the area the Oxley Plains after his superior the Surveyor-General, John Oxley. He also discovered the Abercrombie and Belubula River Valleys. He was the first explorer through the areas that now include the towns of Boorowa and Cowra.

On 1 June 1815 in Eugowra, a town in the Central West region of New South Wales, George William Evans and his group marked a tree at the junction of Lachlan river and a creek which they named Byrnes Creek. This was the furthest west any Europeans had travelled into the country. On 1 June 1815 he was running short of provisions and returned to Bathurst where he arrived on 12 June. This journey opened the way for later explorations, mainly by John Oxley. Evans took part in some of Oxley's expeditions.

Evans returned to Tasmania in 1817 but was again to return to New South Wales to journey with his superior John Oxley on travels into the Lachlan River areas, along the path of the Macquarie River to the Macquarie Marshes and eastwards to the coast to Port Macquarie.[3]

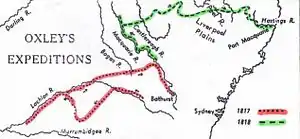

In March 1817, Oxley was instructed to take charge of an expedition to explore and survey the course of the Lachlan River. He left Sydney on 6 April with Evans, as second-in-command, and Allan Cunningham as botanist. Oxley's party reached Bathurst after a week, where they were briefly detained by bad weather. They reached the Lachlan River on 25 April 1817 and commenced to follow its course, with part of the stores being conveyed in boats. As the exploring party travelled westward the country surrounding the rising river was found to be increasingly inundated. On 12 May, west of the present township of Forbes, they found their progress impeded by an extensive marsh. After retracing their route for a short distance they then proceeded in a south-westerly direction, intending to travel overland to the southern Australian coastline. By the end of May the party found themselves in a dry scrubby country. Shortage of water and the death of two horses forced Oxley's return to the Lachlan River. On 23 June the Lachlan River was reached:

- "we suddenly came upon the banks of the river… which we had quitted nearly five weeks before".

They followed the course of the Lachlan River for a fortnight. The party encountered much flooded country, and on 7 July Oxley recorded that:

- "it was with infinite regret and pain that I was forced to come to the conclusion, that the interior of this vast country is a marsh and uninhabitable".

Oxley resolved to turn back and after resting for two days Oxley's party began to retrace their steps along the Lachlan River. They left the Lachlan up-stream of the present site of Lake Cargelligo and crossed to the Bogan River and then across to the upper waters of the Macquarie River, which they followed back to Bathurst (arriving on 29 August 1817).[7]

Oxley travelled to Dubbo on 12 June 1818. He wrote that he had passed that day "over a very beautiful country, thinly wooded and apparently safe from the highest floods..." Later in 1818 Oxley and his men explored the Macquarie River at length before turning west. On 26 August 1818 they climbed a hill and saw before them rich, fertile land (Peel River), near the present site of Tamworth. Continuing further east they crossed the Great Dividing Range passing by the Apsley Falls on 13 September 1818 which he named the Bathurst Falls. He described it as "one of the most magnificent waterfalls we have seen". He discovered and named the Arbuthnot Range, since renamed the Warrumbungle Range. Upon reaching the Hastings River they followed it to its mouth, discovering that it flowed into the sea at a spot which they named Port Macquarie.

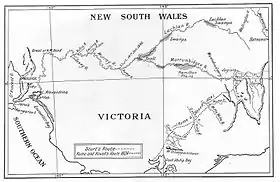

In 1824, Governor Thomas Brisbane asked Hamilton Hume and William Hovell to travel from Hume's station, near modern-day Canberra, to Spencer Gulf (west of modern-day Adelaide). However, they were required to pay their own costs. Hume and Hovell decided that Western Port (in present-day Victoria) was a more realistic goal, and they left with a party of six men. After discovering and crossing the Murrumbidgee and Murray rivers, they eventually reached a site near modern-day Geelong, somewhat west of their intended destination.[8][9]

Inland sea

After the Great Dividing Range had been crossed at numerous points and many rivers were discovered—the Darling, Macquarie, Murray and Murrumbidgee rivers—all of which flowed west, a theory was developed of a vast inland sea into which these rivers flowed. Another reason behind the idea of an inland sea was that Matthew Flinders, who had very carefully mapped much of Australia's coast had discovered no great river delta where these rivers should have emerged by had they reached the coast. The Murray-Darling basin actually drains into Lake Alexandrina. Matthew Flinders had noted this on his maps but viewed from the sea does not look like the outfall of a large watershed, but instead as a gentle tidal basin.

The mystery was solved by Charles Sturt, who in 1829–30 undertook an expedition similar to the one which Hume and Hovell had refused: a trip to the mouth of the Murray River. They followed the Murrumbidgee until it met the Murray, and then found the junction of the Murray and the Darling before continuing on to the mouth of the Murray. The search for an inland sea was an inspiration for many early expeditions west of the Great Dividing Ranges. This quest drove many explorers to extremes of endurance and hardship. Charles Sturt's expedition explained the mystery. It also led to the opening of South Australia to settlement.[10]

The theory of the inland sea had some supporters. Major Thomas Mitchell, the Surveyor-General of New South Wales, set out in 1836 to disprove Sturt's claims and in doing so made a significant discovery. He led an expedition to 'fill in the gaps' left by these previous expeditions. He set off along the Lachlan River, down to the Murray River. He then set off for the southern coast, mapping what is now western Victoria. There he discovered the richest grazing land ever seen to that time and named it Australia Felix. He was knighted for this discovery in 1837. When he reached the coast at Portland Bay, he was surprised to find a small settlement. It had been established by the Henty family, who had sailed across Bass Strait from Van Diemen's Land in 1834, without the authorities being informed.[11] He was meticulous in seeking to record the original Aboriginal place names around the colony, for which reason the majority of place names to this day retain their Aboriginal titles.[12]

The Polish scientist/explorer Count Paul Edmund Strzelecki conducted surveying work in the Australian Alps in 1839 and became the first European to ascend Australia's highest peak, which he named Mount Kosciuszko in honour of the Polish patriot Tadeusz Kosciuszko.[13]

The vast interior

From 1858 onwards, the so-called "Afghan" cameleers and their beasts played an instrumental role in opening up the outback and helping to build infrastructure.[14]

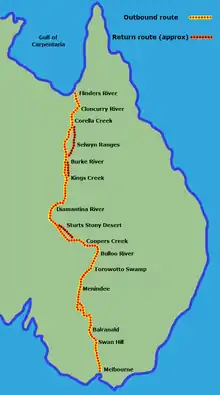

The competition to chart a route for the Australian Overland Telegraph Line spurred a number of cross-continental expeditions. Perhaps the most famous of these was the Burke and Wills expedition led by Robert O'Hara Burke and William John Wills who in 1860–61 led a well equipped expedition from Melbourne to the Gulf of Carpentaria. Due to an unfortunate run of bad luck, oversight and poor leadership, Burke and Wills both died on the return trip.[15]

List of expeditions 1804–1897

Expeditions (in chronological order):

| When | Who | Where |

|---|---|---|

| 1804 | William Paterson | Port Dalrymple, Tamar River, North Esk River (Tasmania) |

| 1813 | Blaxland, Wentworth, and Lawson | From Sydney across the Great Dividing Range via the Blue Mountains; first penetration into inland New South Wales |

| 1817–1818 | John Oxley[16] | Interior of New South Wales; discovered Lachlan River and Macquarie River |

| 1818 | Throsby, Meehan, Hume and Wild | Throsby and Wild discovered an overland route from Sydney to Jervis Bay via the Kangaroo and Lower Shoalhaven rivers Meehan and Hume followed the Shoalhaven upriver and discovered Lake Bathurst and the Goulburn Plains[17] |

| 1820 | Joseph Wild[18] | discovered Lake George[19] |

| 1823 | Currie, Ovens and Wild | Region south of Lake George;[20] discovered Isabella Plains (now a suburb of Canberra), charted the upper reach of the Murrumbidgee River and discovered Monaro[21] |

| 1824 | Hume and Hovell expedition | Sydney to Geelong; discovered Murray River |

| 1828–1829 | Charles Sturt and Hamilton Hume | Macquarie River area; discovered Darling River |

| 1829 | Currie, Drummond, Dr Simmons and Lieut Griffin | South of Fremantle; explored region, now Rockingham and Baldivis, and sighted the Serpentine River[22] |

| 1829 | Dr Collie and Lieut.Preston | discovered Harvey, Collie and Preston rivers |

| 1829–1830 | Charles Sturt | Along the Murrumbidgee River; found and named Murray River, and determined that western-flowing rivers flowed into the Murray-Darling basin |

| 1830 | John Molloy | Blackwood River, Western Australia |

| 1830–1834 | Alfred and John Bussell | Blackwood River and Busselton, Western Australia |

| 1831 | Robert Dale and George Fletcher Moore | Avon River area in Western Australia |

| 1831 | Collet Barker | Mount Lofty and the Murray Mouth |

| 1834 | Frederick Ludlow | Augusta to Perth; discovered Capel River |

| 1834–1836 | George Fletcher Moore | Avon River and Swan River; discovered that they are the same river; discovered rich pastoral land near the Moore River |

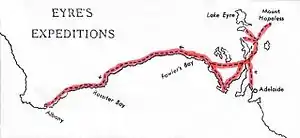

| 1839–1841 | Edward John Eyre[23] | The Flinders Ranges and Nullarbor Plain |

| 1840 | Paweł Strzelecki[24] | Ascended and named Mount Kosciuszko, New South Wales |

| 1840 | Patrick Leslie | Condamine River, New South Wales |

| 1840–1842 | Clement Hodgkinson[25] | North-eastern New South Wales, from Port Macquarie to Moreton Bay |

| 1844 | Charles Sturt | North-western New South Wales and north-eastern South Australia; discovered the Simpson Desert |

| 1847 | Anthony O'Grady Lefroy and Alfred Durlacher | Gingin, Western Australia |

| 1854 | Austin expedition of 1854 – Robert Austin, Kenneth Brown | Geraldton, Mount Magnet, Murchison River |

| 1858–1860 | John McDouall Stuart[26] | North-western South Australia; discovered water sources used as staging points for later expeditions; found and named Finke River, MacDonnell Ranges, Tennant Creek |

| 1860 | Burke and Wills expedition including Robert O'Hara Burke, William John Wills | Melbourne to Gulf of Carpentaria (traversing Australia south to north); determined non-existence of inland sea |

| 1897 | Frank Hann[27] | Pilbara region of Western Australia; named Lake Disappointment |

Other 19th-century explorers

Other explorers by land (in alphabetical order):

20th-century explorers

By the turn of the 20th century, most of the major geographical features of Australia had been discovered by European explorers. However, there are some 20th-century people who are considered explorers. They include:

- Ted Colson (First to cross the Simpson Desert in 1936.)[37]

- Donald George Mackay (Five major expeditions to survey and accurately map the Northern Territory, discoverer of Lake Mackay)[38]

- Cecil Madigan (Major scientific expedition to the Simpson Desert in 1939. In 1930, Madigan coined the name "Simpson Desert" after Alfred Allen Simpson, following an aerial survey.)[39]

- Len Beadell (Surveyor, road builder, author.)[40]

- In 1928, the Royal Australian Air Force started photographing Australian land features from aircraft,[41] and in 1929, the Australian Survey Corps had aerial photos of coastal areas north of Sydney. Urbanized areas were generally first photographed from aircraft during World War II, and the Air Force produced imagery of 1.25 million square miles of northern and central Australia between 1947 and 1952.

21st-century activity

- Google Street View sent cars across Australia to create a visual map of the country's streetscapes, starting in urban areas around 2008. While the service had a brief hiatus due to concerns over collecting wi-fi data from 2010 to 2011,[42][43] mapping with the Google cars resumed and continued until at least 2015.

Indigenous Australians participating in European exploration

A number of Indigenous Australians participated in the European exploration of Australia. They include:

- Jackey Jackey (aka Galmahra), who accompanied Kennedy's expedition[44]

- Tommy Windich, who joined John Forrest in his search for Ludwig Leichhardt

- Wylie, who accompanied Eyre's expedition across the Nullarbor

Naturalists and other scientists

There are a number of naturalists and other scientists closely associated with European exploration of Australia. They include:

- Daniel Solander, accompanied Cook's 1770 expedition[45]

- Jacques Labillardière, accompanied Bruni d'Entrecasteaux

- Allan Cunningham, accompanied Oxley's 1817 expedition[46]

- John Gilbert, accompanied Leichhardt's expedition

- Ferdinand von Mueller, accompanied Augustus Gregory's expedition[47]

- Jean Baptiste Leschenault de la Tour, François Péron and Charles Alexander Lesueur, accompanied Baudin's 1801 expedition

- John Lhotsky[48]

- Gerard Krefft[49]

- Olive Pink[50]

- Scientists of the Horn Expedition of 1894, including Walter Baldwin Spencer, Edward Charles Stirling and Ralph Tate[51]

Uncategorised explorers

References

- Bladen, F. M., ed. (1897), Historical records of New South Wales, Volume 5—King, 1803–1805, Sydney: Charles Potter, Government Printer, pp. 494–500, archived from the original on 30 March 2011

- Gregory Blaxland:"A Journal of a Tour of Discovery across the Blue Mountains, New South Wales in the Year 1813", in George Mackaness (Ed.)(1965) Fourteen Journeys Over the Blue Mountains of New South Wales 1813–1841, Horwitz Publications, The Grahame Book Company, Sydney, Australia.

- Spencer Harvey (2010). The Story of Kings Parade. Bathurst: Bathurst Regional Council. p. 29.

- "Evans, George William (1778–1852)". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Project Gutenberg Australia. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- "William Cox". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Project Gutenberg Australia. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- Local History, Bathurst City, Bathurst Visitor Information Centre Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine(accessed 10 October 2013)

- Oxley, John (1820). "Journal of an Expedition in Australia – Part 1". Journals of Two Expeditions into the Interior of New South Wales. John Murray. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- See full article Hume and Hovell expedition and numerous summaries such as; Jan Bassett (1986) The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Australian History. p. 136. Oxford University Press, Melbourne ISBN 0-19-554422-6

- Hamilton Hume and William Hovell (1831) Journey of Discovery to Port Phillip District at Project Gutenberg

- H.J. Gibbney (1967) "Sturt, Charles (1795–1869)" Australian Dictionary of Biography

- D.W.A. Baker (1967) "Sir Thomas Livingstone (1792–1855)" Australian Dictionary of Biography

- Biography – Sir Thomas Livingstone Mitchell – Australian Dictionary of Biography. Adbonline.anu.edu.au. Retrieved on 12 July 2013.

- Biography – Sir Paul Edmund de Strzelecki – Australian Dictionary of Biography. Adbonline.anu.edu.au. Retrieved on 12 July 2013.

- "Afghan cameleers in Australia". australia.gov.au. 15 August 2014. Archived from the original on 15 August 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- Alan Moorehead (1963) Cooper's Creek. MacMillan, Melbourne and Sydney. ISBN 0-333-22909-6

- E.W. Dunlop (1967) "Oxley, John Joseph William Molesworth (1784?–1828)" Australian Dictionary of Biography

- Year Book Australia 1931 – Canberra Past and Present

- Vivienne Parsons (1967)"Wild, Joseph (1773?–1847)" Australian Dictionary of Biography

- NSW Government Collections, Joseph Wild

- M.J.Currie, Journal of an excursion to the south of Lake George 1823

- The Discovery of Monaro

- Reference to the Serpentine in Murray River

- Geoffrey Dutton (1966) "Eyre, Edward John (1815–1901)" Australian Dictionary of Biography

- Helen Heney (1967) "Strzelecki, Sir Paul Edmund de [Count Strzelecki] (1797–1873)" , Dictionary of Australian Biography

- K.A. Patterson (1972) "Hodgkinson, Clement (1818–1893)" Dictionary of Australian Biography

- Deirdre Morris (1976) "Stuart, John McDouall (1815–1866)" Dictionary of Australian Biography

- G.C.Bolton (1972) "Hann, Frank Hugh (1846–1921)" Dictionary of Australian Biography

- G.C.Bolton (1981) "Forrest, Alexander (1849–1901)" Dictionary of Australian Biography

- F.K.Crowley (1981) "Forrest, Sir John [Baron Forrest] (1847–1918)" Dictionary of Australian Biography

- Louis Green (1972) "Giles, Ernest (1835–1897)" Dictionary of Australian Biography

- P.Serle. (1961) "Grey, Sir George (1812–1898)" Dictionary of Australian Biography

- Edgar Beale (1967) "Kennedy, Edmund Besley Court (1818–1848)" Dictionary of Australian Biography

- E.W. Dunlop (1967) "Lawson, William (1774–1850)" Dictionary of Australian Biography

- Renee Erdos (1967) "Leichhardt, Friedrich Wilhelm Ludwig (1813–1848)" Dictionary of Australian Biography

- Tim Flannery (Ed) (1996) Watkin Tench, 1788; Comprising a narrative of the expedition to Botany Bay and a complete account of the settlement at Port Jackson. Text Publishing, Melbourne. ISBN 1-875847-27-8

- Denison Deasey (1976) "Warburton, Peter Egerton (1813–1889)" Dictionary of Australian Biography

- C. J. Horne (1993) "Colson, Edmund Albert (1881–1950)" Australian Dictionary of Biography

- David Carment, (1986) "Mackay, Donald George (1870–1958) Australian Dictionary of Biography

- L. W. Parkin (1986) "Madigan, Cecil Thomas (1889–1947)" Australian Dictionary of Biography

- "ABC TV, George Negus Tonight. Broadcast 21/06/2004". Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- https://www.nla.gov.au/selected-library-collections/aerial-photographs-collection

- Chloe Herrick. "Google: Street View cars no longer in operation in Australia". Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- "Google Australia lays out future Street View privacy measures – Street View, security, privacy, Google, data – Privacy – Security". Techworld. 5 May 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- Edgar Beale (1967) "Jackey Jackey ( –1854)" Australian Dictionary of Biography

- L.A. Gilbert (1967) "Solander, Daniel (1733–1782)" Australian Dictionary of Biography

- T.M.Perry (1967) "Cunningham, Allan (1791–1839)" Australian Dictionary of Biography

- Deirdre Morris (1974) "Mueller, Sir Ferdinand Jakob Heinrich von [Baron von Mueller] (1825–1896)" Australian Dictionary of Biography

- G.P.Whitley (1974) "Lhotsky, John (1795?–1866?)" Australian Dictionary of Biography

- G. P. Whitley, Martha Rutledge(1974) "Krefft, Johann Ludwig Gerard (Louis) (1830–1881)" Australian Dictionary of Biography

- Julie Marcus (2002) "Pink, Olive Muriel (1884–1975)" Australian Dictionary of Biography

- Treasures of the Museum Victoria

- A.H. Chisholm (1969) "Calvert, James Snowden (1825–1884)" Australian Dictionary of Biography

- See numerous books by Michael Terry, dating from (1925) Across Unknown Australia, Herbert Jenkins, London, to (1974) War of the Warramullas. Rigby Limited, Australia. ISBN 0-85179-790-3

Further reading

- Bennett, S. (1867). The history of Australian discovery and colonisation. Sydney: Hanson and Bennett.

- Ridpath, J. C. (1899). Ridpath's universal history; an account of the origin, primitive condition, and race development of the greater divisions of mankind, and also of the principal events in the evolution and progress of nations from the beginnings of the civilized life to the close of the nineteenth century. Cincinnati: Jones Brothers Pub.