Goyocephale

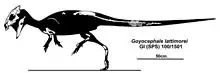

Goyocephale is an extinct genus of pachycephalosaurian ornithischian that lived in Mongolia during the Late Cretaceous about 76 million years ago.[1] It was first described in 1982 by Perle, Teresa Maryańska and Osmólska for a disarticulated skeleton with most of a skull, part of the forelimb and hindlimb, some of the pelvic girdle, and some vertebrae. Perle et al. named the remains Goyocephale lattimorei, from the Mongolian goyo, meaning "decorated", and the Ancient Greek kephale, for head. The species name honours Owen Lattimore.[2]

| Goyocephale | |

|---|---|

| |

| Holotype skull, dorsal view | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | †Ornithischia |

| Family: | †Pachycephalosauridae |

| Genus: | †Goyocephale Perle et al., 1982 |

| Species: | †G. lattimorei |

| Binomial name | |

| †Goyocephale lattimorei Perle et al., 1982 | |

Description

Goyocephale is known from a partial skull, including both mandibles, the skull roof, part of the occiput, part of the braincase region, the posterior skull, the premaxilla, and the maxilla. The posterior edge of the skull roof, at the edge of the squamosal bones, has many small bony bumps, which would have been the base of small horns in life. A feature shared with pachycephalosaurids, Goyocephale had a heterodont dentition, with large caniniform premaxilla teeth, followed by a diastema between the premaxilla and the maxilla, and the regular sub-triangular teeth in the maxilla. Teeth in the premaxilla become larger farther posterior, with the last being the largest. The mandible teeth are similar, with the first tooth being caniniform, and the remainder low and sub-triangular.[2]

Of the vertebrae, only the atlas bone (the first cervical vertebra) and the sacrum and tail vertebrae are preserved. The sacrum includes four vertebrae, which are not strongly fused and incomplete. On the ventral surface of the second sacral centrum is a length-wise ridge, with a groove along its midline. The first and second tail vertebrae were found articulated with the sacrum, although they are much weakly fused than the sacral vertebrae. In addition, they can be distinguished from the sacrum because they possess zygapophyses that are not fused together, although they also preserve a ventral groove.[2]

The limb and girdle bones are well-preserved, and show many features. The humerus is strongly bowed, with a nearly equal expansion on the distal and proximal ends. It also shows a thick but weak deltopectoral crest (anterior projection on the humerus), and weakly separated condyles on the distal end. The ilium bone shows a morphology typical for pachycephalosaurs, with a thin and horizontally elongate preacetabular process (front extension of the ilium), and a wide ridge extending outwards from the top edge of the postacetabular process (hind ilium extension). Also, the two preacetabular processes are strongly diverged in dorsal view, and in lateral view the ilium is almost straight and the postacetabular process is sub-rectangular. The tibia shows a pachycephalosaur design, and no tarsal bones appear to be articulated. The foot of Goyocephale is partially preserved, and at least three digits (digits II, III and IV) were present. On each toe, the unguals are triangular but not recurved, with the ungulate of the third toe being the largest.[2]

Classification

Goyocephale is a primitive pachycephalosaurian, and was originally included in the family Homalocephalidae, which united the genus with Homalocephale, which also has a flat skull roof. Goyocephale is distinguished from Homalocephale by its overall proportions, the shape of its supratemporal fenestra, and heterodont dentition, although the two share multiple features.[2] However, many more recent phylogenetic analyses tend to find Homalocephalidae to be a paraphyletic family, with the genera included simply being consecutive branches sister to Pachycephalosauridae,[3] or as consecutive branches primitive to Prenocephale but within Pachycephalosauridae. A cladogram illustrating the latter hypothesis is shown below.[4]

| Pachycephalosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

However, one phylogenetic analysis did support a monophyletic Homalocephalidae, with Goyocephale, Homalocephale and Wannanosaurus being the most derived pachycephalosaurians, and their sister taxa being Prenocephale and Tylocephale. This positioning of all the taxa from Asia as most derived would support that pachycephalosaurians evolved in North America, where they retained their greatest diversity, before migrating to Asia. In addition, the oldest genera that belong in the group are North American, which provides further support for this position.[5]

References

- Sullivan, R.M. (2006). "A taxonomic review of the Pachycephalosauridae (Dinosauria: Ornithischia)" (PDF). In Lucas, Spencer G.; Sullivan, Robert M. (eds.). Late Cretaceous vertebrates from the Western Interior. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 35. pp. 347–366.

- Perle, A.; Maryańska, T.; Osmólska, H. (1982). "Goyocephale lattimorei gen. et sp. n., a new flat -headed pachycephalosaur (Ornithlschia , Dinosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 27 (1–4): 115–127.

- Mahito Watabe, Khishigjaw Tsogtbaatar and Robert M. Sullivan (2011). "A new pachycephalosaurid from the Baynshire Formation (Cenomanian-late Santonian), Gobi Desert, Mongolia" (PDF). Fossil Record 3. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Bulletin. 53: 489–497.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Schott, R.K.; Evans, D.C. (2016). "Cranial variation and systematics of Foraminacephale brevis gen. nov. and the diversity of pachycephalosaurid dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Cerapoda) in the Belly River Group of Alberta, Canada". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. doi:10.1111/zoj.12465.

- Longrich, N.R.; Sankey, J.; Tanke, D. (2010). "Texacephale langstoni, a new genus of pachycephalosaurid (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the upper Campanian Aguja Formation, southern Texas, USA". Cretaceous Research. 31 (2): 274–284. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2009.12.002.